Ravn virus

| Ravn virus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Filoviridae |

| Genus: | Marburgvirus |

| Species: | |

| Virus: | Ravn virus

|

| Marburg (Ravn) virus disease | |

|---|---|

| |

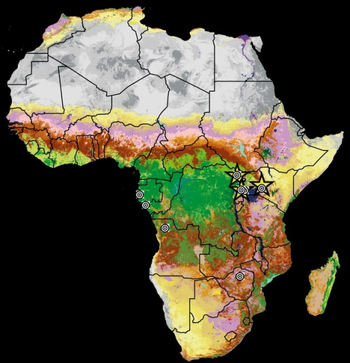

| Occurrences of Marburg virus strains across Africa, 'more frequent' Marburg virus disease are shown as bulls eyes, whereas occurrences of RAVN are shown as yellow stars. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Frequency | Lua error in Module:PrevalenceData at line 5: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

Ravn virus (/ˈrævən/;[1] RAVV) is a close relative of Marburg virus (MARV). RAVV causes Marburg virus disease in humans and nonhuman primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic fever.[2] RAVV is a Select agent,[3] World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment),[4] National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Category A Priority Pathogen,[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Category A Bioterrorism Agent,[6] and listed as a Biological Agent for Export Control by the Australia Group.[7]

Term use

Ravn virus (today abbreviated RAVV, but then considered identical to Marburg virus) was first described in 1987 and is named after a 15-year old Danish boy who fell ill and died from it.[8] Today, the virus is classified as one of two members of the species Marburg marburgvirus, which is included into the genus Marburgvirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales. The name Ravn virus is derived from Ravn (the name of the Danish patient from whom this virus was first isolated) and the taxonomic suffix virus.[1]

Previous designations

Ravn virus was first introduced as a new subtype of Marburg virus in 1996.[8] In 2006, a whole-genome analysis of all marburgviruses revealed the existence of five distinct genetic lineages. The genomes of representative isolates of four of those lineages differed from each other by only 0-7.8% on the nucleotide level, whereas representatives of the fifth lineage, including the new "subtype", differed from those of the other lineages by up to 21.3%.[9]

Consequently, the fifth genetic lineage was reclassified as a virus, Ravn virus (RAVV), distinct from the virus represented by the four more closely related lineages, Marburg virus (MARV).[1]

Virus inclusion criteria

A virus that fulfills the criteria for being a member of the species Marburg marburgvirus is a Ravn virus if it has the properties of Marburg marburgviruses and if its genome diverges from that of the prototype Marburg marburgvirus, Marburg virus variant Musoke (MARV/Mus), by ≥10% but from that of the prototype Ravn virus (variant Ravn) by <10% at the nucleotide level.[1]

Disease

Marburg virus disease is a severe type of viral hemorrhagic fever in humans.[10] Initial symptoms typically include fever, headache, and muscle pain.[11] A few days later a rash, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain may occur.[11] Onset of symptoms is typically 5 to 10 days following exposure.[11] Complications may include liver failure, delirium, pancreatitis, and severe bleeding.[11]

The cause is Marburgvirus, of which there are two types Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus .[2] These viruses normally circulates among African fruit bats, without resulting in ill affects.[12] Spread can occur from these bats to people and than between people.[10] Spread between people is by direct or indirect contact with contaminated body fluids, including during sex.[13][10] Diagnosis is by blood tests.[14] It presents similar to Ebola virus disease (EVD).[10]

-

Petechiae

-

Headache

Prevention involves avoiding bats in central Africa and using appropriate personal protective equipment when caring for sick people.[15] Treatment involves supportive care and this improves outcomes.[10] This may include intravenous fluids, blood products, oxygen therapy, and electrolytes.[16] About half of those who are infected die as a result.[10]

MVD is rare.[12] It generally occurs as outbreaks within Africa.[12] The disease was initially recognized in 1967 and since then 588 cases have been diagnosed.[12][10] Other primates may also be affected.[12]

MVD due to RAVV infection cannot be differentiated from MVD caused by MARV by clinical observation alone. [17]

Ecology

In 2009, the successful isolation of infectious RAVV was reported from caught healthy Egyptian rousettes (Rousettus aegyptiacus).[18]

This isolation, together with the isolation of infectious MARV, strongly suggests that Old World fruit bats are involved in the natural maintenance of marburgviruses.[18][19]

Evolution

The viral strains fall into two clades: Ravn virus and Marburg virus.[20] The Marburg strains can be divided into two: A and B. The A strains were isolated from Uganda (five from 1967), Kenya (1980) and Angola (2004–2005) while the B strains were from the Democratic Republic of the Congo epidemic (1999–2000) and a group of Ugandan isolates isolated in 2007–2009.[21][22][20]

Epidemiology

In the past, RAVV has caused the following MVD outbreaks:

| Year | Geographic location | Human cases/deaths (case-fatality rate) |

| 1987 | Kenya | 1/1 (100%)[8] |

| 1998–2000 | Durba and Watsa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | unknown (A total of 154 cases and 128 deaths of marburgvirus infection were recorded during this outbreak. The case fatality was 83%. Two different marburgviruses, RAVV and Marburg virus (MARV), cocirculated and caused disease. It has never been published how many cases and deaths were due to RAVV or MARV infection)[23][24][25] |

| 2007 | Uganda | 0/1 (0%)[18][26] |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kuhn, J. H.; Becker, S.; Ebihara, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Johnson, K. M.; Kawaoka, Y.; Lipkin, W. I.; Negredo, A. I.; Netesov, S. V.; Nichol, S. T.; Palacios, G.; Peters, C. J.; Tenorio, A.; Volchkov, V. E.; Jahrling, P. B. (2010). "Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations". Archives of Virology. 155 (12): 2083–2103. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. PMC 3074192. PMID 21046175.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Spickler, Anna. "Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus Infections" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-30. Retrieved 2014-10-19.

- ↑ US Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "National Select Agent Registry (NSAR)". Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ US Department of Health and Human Services. "Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 5th Edition". Archived from the original on 2020-04-23. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ US National Institutes of Health (NIH), US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). "Biodefense - NIAID Category A, B, and C Priority Pathogens". Archived from the original on 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases". Archived from the original on 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ The Australia Group. "List of Biological Agents for Export Control". Archived from the original on 2011-08-06. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Johnson, E. D.; Johnson, B. K.; Silverstein, D.; Tukei, P.; Geisbert, T. W.; Sanchez, A. N.; Jahrling, P. B. (1996). "Characterization of a new Marburg virus isolated from a 1987 fatal case in Kenya". Archives of Virology. Supplementum. 11: 101–114. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-7482-1_10. ISBN 978-3-211-82829-8. PMID 8800792.

- ↑ Towner, J. S.; Khristova, M. L.; Sealy, T. K.; Vincent, M. J.; Erickson, B. R.; Bawiec, D. A.; Hartman, A. L.; Comer, J. A.; Zaki, S. R.; Ströher, U.; Gomes Da Silva, F.; Del Castillo, F.; Rollin, P. E.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Nichol, S. T. (2006). "Marburgvirus Genomics and Association with a Large Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreak in Angola". Journal of Virology. 80 (13): 6497–6516. doi:10.1128/JVI.00069-06. PMC 1488971. PMID 16775337.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 "Marburg virus disease". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Signs and Symptoms | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 "About Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ "Transmission | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ "Ebola Virus Disease & Marburg Virus Disease - Chapter 3 - 2018 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC". wwwnc.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ↑ "Prevention | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ "Treatment | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ Hunter, Nicole; Rathish, Balram (2022). "Marburg Fever". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Towner, J. S.; Amman, B. R.; Sealy, T. K.; Carroll, S. A. R.; Comer, J. A.; Kemp, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Paddock, C. D.; Balinandi, S.; Khristova, M. L.; Formenty, P. B.; Albarino, C. G.; Miller, D. M.; Reed, Z. D.; Kayiwa, J. T.; Mills, J. N.; Cannon, D. L.; Greer, P. W.; Byaruhanga, E.; Farnon, E. C.; Atimnedi, P.; Okware, S.; Katongole-Mbidde, E.; Downing, R.; Tappero, J. W.; Zaki, S. R.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Nichol, S. T.; Rollin, P. E. (2009). Fouchier, Ron A. M. (ed.). "Isolation of Genetically Diverse Marburg Viruses from Egyptian Fruit Bats". PLOS Pathogens. 5 (7): e1000536. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000536. PMC 2713404. PMID 19649327.

- ↑ Precious-Ogbueri, Ruhuoma; Nwalozie, Rhoda; Konne, Felix Eedee; Nyenke, Clement Ugochukwu (17 September 2022). "Marbug Virus Disease: An Overview". Asian Journal of Research in Infectious Diseases: 15–21. doi:10.9734/ajrid/2022/v11i2213. ISSN 2582-3221. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Zehender G, Sorrentino C, Veo C, Fiaschi L, Gioffrè S, Ebranati E, et al. (October 2016). "Distribution of Marburg virus in Africa: An evolutionary approach". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 44: 8–16. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2016.06.014. hdl:2434/425196. PMID 27282469. S2CID 1704025.

- ↑ Dowdle, W. R. (1976). "Marburg virus". Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization. 10 (4): 333–334. ISSN 0085-4638. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Kortepeter, Mark G.; Dierberg, Kerry; Shenoy, Erica S.; Cieslak, Theodore J. (October 2020). "Marburg virus disease: A summary for clinicians". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 99: 233–242. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.042. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Bertherat, E.; Talarmin, A.; Zeller, H. (1999). "Democratic Republic of the Congo: Between civil war and the Marburg virus. International Committee of Technical and Scientific Coordination of the Durba Epidemic". Médecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Santé Colonial. 59 (2): 201–204. PMID 10546197.

- ↑ Bausch, D. G.; Borchert, M.; Grein, T.; Roth, C.; Swanepoel, R.; Libande, M. L.; Talarmin, A.; Bertherat, E.; Muyembe-Tamfum, J. J.; Tugume, B.; Colebunders, R.; Kondé, K. M.; Pirad, P.; Olinda, L. L.; Rodier, G. R.; Campbell, P.; Tomori, O.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Rollin, P. E. (2003). "Risk Factors for Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (12): 1531–1537. doi:10.3201/eid0912.030355. PMC 3034318. PMID 14720391.

- ↑ Bausch, D. G.; Nichol, S. T.; Muyembe-Tamfum, J. J.; Borchert, M.; Rollin, P. E.; Sleurs, H.; Campbell, P.; Tshioko, F. K.; Roth, C.; Colebunders, R.; Pirard, P.; Mardel, S.; Olinda, L. A.; Zeller, H.; Tshomba, A.; Kulidri, A.; Libande, M. L.; Mulangu, S.; Formenty, P.; Grein, T.; Leirs, H.; Braack, L.; Ksiazek, T.; Zaki, S.; Bowen, M. D.; Smit, S. B.; Leman, P. A.; Burt, F. J.; Kemp, A.; Swanepoel, R. (2006). "Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Associated with Multiple Genetic Lineages of Virus" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (9): 909–919. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051465. PMID 16943403. Archived from the original on 2022-12-29. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

- ↑ Adjemian, J.; Farnon, E. C.; Tschioko, F.; Wamala, J. F.; Byaruhanga, E.; Bwire, G. S.; Kansiime, E.; Kagirita, A.; Ahimbisibwe, S.; Katunguka, F.; Jeffs, B.; Lutwama, J. J.; Downing, R.; Tappero, J. W.; Formenty, P.; Amman, B.; Manning, C.; Towner, J.; Nichol, S. T.; Rollin, P. E. (2011). "Outbreak of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Among Miners in Kamwenge and Ibanda Districts, Uganda, 2007". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (Suppl 3): S796–S799. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir312. PMC 3203392. PMID 21987753.

Further reading

- Klenk, Hans-Dieter (1999), Marburg and Ebola Viruses. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, vol. 235, Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-64729-4

- Klenk, Hans-Dieter; Feldmann, Heinz (2004), Ebola and Marburg Viruses - Molecular and Cellular Biology, Wymondham, Norfolk, UK: Horizon Bioscience, ISBN 978-0-9545232-3-7

- Kuhn, Jens H. (2008), Filoviruses - A Compendium of 40 Years of Epidemiological, Clinical, and Laboratory Studies. Archives of Virology Supplement, vol. 20, Vienna, Austria: SpringerWienNewYork, ISBN 978-3-211-20670-6

- Martini, G. A.; Siegert, R. (1971). Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-05199-4.

- Ryabchikova, Elena I.; Price, Barbara B. (2004), Ebola and Marburg Viruses - A View of Infection Using Electron Microscopy, Columbus, Ohio, USA: Battelle Press, ISBN 978-1-57477-131-2

External links

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Archived 2021-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages with script errors

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Animal viral diseases

- Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers

- Biological weapons

- Hemorrhagic fevers

- Marburgviruses

- Tropical diseases

- Primate diseases

- Virus-related cutaneous conditions

- Zoonoses

- Infraspecific virus taxa

- Bat virome