RAD21

Double-strand-break repair protein rad21 homolog is a protein that in humans is encoded by the RAD21 gene.[5][6] RAD21 (also known as Mcd1, Scc1, KIAA0078, NXP1, HR21), an essential gene, encodes a DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair protein that is evolutionarily conserved in all eukaryotes from budding yeast to humans. RAD21 protein is a structural component of the highly conserved cohesin complex consisting of RAD21, SMC1A, SMC3, and SCC3 [ STAG1 (SA1) and STAG2 (SA2) in multicellular organisms] proteins, involved in sister chromatid cohesion.

Discovery

rad21 was first cloned by Birkenbihl and Subramani in 1992 [7] by complementing the radiation sensitivity of the rad21-45 mutant fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and the murine and human homologs of S. pombe rad21 were cloned by McKay, Troelstra, van der Spek, Kanaar, Smit, Hagemeijer, Bootsma and Hoeijmakers.[8] The human RAD21 (hRAD21) gene is located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 8 at position 24.11 (8q24.11).[8][9] In 1997, RAD21 was independently discovered by two groups to be a major component of the chromosomal cohesin complex,[10][11] and its dissolution by the cysteine protease Separase at the metaphase to anaphase transition results in the separation of sister chromatids and chromosomal segregation.[12]

Structure

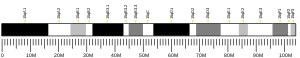

RAD21, belongs to a superfamily of eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteins called a-Kleisins,[13] is a nuclear phospho-protein, ranges in size from 278aa in the house lizard (Gekko Japonicus) to 746aa in the killer whale (Orcinus Orca), with a median length of 631aa in most vertebrate species including humans. RAD21 proteins are most conserved at the N-terminus (NT) and C-terminus (CT), which bind to SMC3 and SMC1, respectively. The STAG domain in the middle of RAD21, which binds to SCC3 (SA1/SA2), is also conserved (Figure 1). These proteins have nuclear localization signals, an acidic-basic stretch and an acidic stretch (Figure 1), which is consistent with a chromatin-binding role. RAD21 is cleaved by several proteases including Separase[12][14][15] and Calcium-dependent cysteine endopeptidase Calpain-1[16] during mitosis and Caspases during apoptosis.[17][18]

Interactions

RAD21 binds to the V-shaped SMC1 and SMC3 heterodimer, forming a tripartite ring-like structure,[20] and then recruits SCC3 (SA1/SA2). The 4 element-complex is called the cohesin complex (Figure 2). Currently, there are two major competing models of sister chromatid cohesion (Figure 2B). The first one is the one-ring embrace model,[21] and the second one is the dimeric handcuff-model.[22][23] The one-ring embrace model posits that a single cohesin ring traps two sister chromatids inside, while the two-ring handcuff model proposes trapping of each chromatid individually. According to the handcuff model, each ring has one set of RAD21, SMC1, and SMC3 molecules. The handcuff is established when two RAD21 molecules move into anti-parallel orientation that is enforced by either SA1 or SA2.[22]

The N-terminal domain of RAD21 contains two α-helices that forms a three helical bundle with the coiled coil of SMC3.[20] The central region of RAD21 is thought to be largely unstructured but contains several binding sites for regulators of cohesin. This includes a binding site for SA1 or SA2,[27] recognition motifs for separase, caspase, and calpain to cleave,[12][16][17][18] as well as a region that is competitively bound by PDS5A, PDS5B or NIPBL.[28][29][30] The C-terminal domain of RAD21 forms a winged helix that binds two β-sheets in the Smc1 head domain.[31]

WAPL releases cohesin from DNA by opening the SMC3-RAD21 interface thereby allowing DNA to pass out of the ring.[32] Opening of this interface is regulated by ATP-binding by the SMC subunits. This causes the ATPase head domains to dimerise and deforms the coiled coil of SMC3 therefore disrupting the binding of RAD21 to the coiled coil.[33]

A total of 285 RAD21-interactants have been reported[34] that function in wide range of cellular processes, including mitosis, regulation of apoptosis, chromosome dynamics, chromosomal cohesion, replication, transcription regulation, RNA processing, DNA damage response, protein modification and degradation, and cytoskeleton and cell motility (Figure 3).[35]

Function

RAD21 plays multiple physiological roles in diverse cellular functions (Figure 4). As a subunit of the cohesin complex, RAD21 is involved in sister chromatid cohesion from the time of DNA replication in S phase to their segregation in mitosis, a function that is evolutionarily conserved and essential for proper chromosome segregation, chromosomal architecture, post-replicative DNA repair, and the prevention of inappropriate recombination between repetitive regions.[14][26] RAD21 may also play a role in spindle pole assembly during mitosis [36] and progression of apoptosis.[17][18] In interphase, cohesin may function in the control of gene expression by binding to numerous sites within the genome. As a structural component of the cohesin complex, RAD21 also contributes to various chromatin-associated functions, including DNA replication,[37][38][39][40][41] DNA damage response (DDR),[42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50] and most importantly, transcriptional regulation.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58] Numerous recent functional and genomic studies have implicated chromosomal cohesin proteins as critical regulators of hematopoietic gene expression.[59][60][61][62][63]

As a part of cohesin complex, functions of Rad21 in the regulation of gene expression include: 1) allele-specific transcription by interacting with the boundary element CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF),[51][52][53][57][64][65] 2) tissue-specific transcription by interacting with tissue-specific transcription factors,[53][66][67][68][69][70] 3) general progression of transcription by communicating with the basal transcription machinery,[54][69][71][72] and 4) RAD21 co-localization with CTCF-independent pluripotency factors (Oct4, Nanog, Sox4, and KLF2). RAD21 cooperates with CTCF,[73] tissue-specific transcription factors, and basal transcription machinery to regulate transcription dynamically.[74] Also, to effectuate proper transcription activation, cohesin loops chromatin to bring two distant regions together.[65][70] Cohesin may also act as a transcription insulator to ensure repression.[51] Thus, RAD21 can affect both activation and repression of transcription. Enhancers that promote transcription and insulators that block transcription are located in conserved regulatory elements (CREs) on chromosomes, and cohesins are thought to physically connect distant CREs with gene promoters in a cell-type specific manner to modulate transcriptional outcome.[75]

In meiosis, REC8 is expressed and replaces RAD21 in the cohesin complex. REC8-containing cohesin generates cohesion between homologous chromosomes and sister chromatids which can persist for years in the case of mammalian oocytes.[76][77] RAD21L is a further paralog of RAD21 that has a role in meiotic chromosome segregation.[78] The major role of Rad21L cohesin complex is in homologue pairing and synapsis, not in sister chromatid cohesion, whereas Rec8 most likely functions in sister chromatid cohesion. Intriguingly, concomitantly with the disappearance of RAD21L, Rad21 appears on the chromosomes in late pachytene and mostly dissociates after diplotene onward.[78][79] The function of Rad21 cohesin that transiently appears in late prophase I is unclear.

Germline heterozygous or homozygous missense mutations in RAD21 have been associated with human genetic disorders, including developmental diseases such as Cornelia de Lange syndrome[80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90] and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction called Mungan syndrome,[91][92] respectively, and collectively termed as cohesinopathies. Somatic mutations and amplification of the RAD21 have also been widely reported in both human solid and hematopoietic tumors.[59][60][75][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113]

Notes

The 2020 version of this article was updated by an external expert under a dual publication model. The corresponding academic peer reviewed article was published in Gene and can be cited as: Haizi Cheng, Nenggang Zhang, Debananda Pati (17 July 2020). "Cohesin Subunit RAD21: from Biology to Disease". Gene. Gene Wiki Review Series: 144966. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2020.144966. ISSN 0378-1119. PMC 7949736. PMID 32687945. Wikidata Q97597551. |

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000164754 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022314 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ McKay MJ, Troelstra C, van der Spek P, et al. (Jan 1997). "Sequence conservation of the rad21 Schizosaccharomyces pombe DNA double-strand break repair gene in human and mouse". Genomics. 36 (2): 305–15. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0466. hdl:1765/3107. PMID 8812457.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: RAD21 RAD21 homolog (S. pombe)".

- ^ Birkenbihl RP, Subramani S (December 1992). "Cloning and characterization of rad21 an essential gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe involved in DNA double-strand-break repair". Nucleic Acids Research. 20 (24): 6605–11. doi:10.1093/nar/20.24.6605. PMC 334577. PMID 1480481.

- ^ a b McKay MJ, Troelstra C, van der Spek P, et al. (September 1996). "Sequence conservation of the rad21 Schizosaccharomyces pombe DNA double-strand break repair gene in human and mouse". Genomics. 36 (2): 305–15. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0466. hdl:1765/3107. PMID 8812457.

- ^ Nomura N, Nagase T, Miyajima N, et al. (1994-01-01). "Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. II. The coding sequences of 40 new genes (KIAA0041-KIAA0080) deduced by analysis of cDNA clones from human cell line KG-1". DNA Research. 1 (5): 223–9. doi:10.1093/dnares/1.5.223. PMID 7584044.

- ^ Guacci V, Koshland D, Strunnikov A (October 1997). "A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae". Cell. 91 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80008-8. PMC 2670185. PMID 9335334.

- ^ Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K (October 1997). "Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids". Cell. 91 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80007-6. PMID 9335333. S2CID 18572651.

- ^ a b c Uhlmann F, Lottspeich F, Nasmyth K (July 1999). "Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1". Nature. 400 (6739): 37–42. Bibcode:1999Natur.400...37U. doi:10.1038/21831. PMID 10403247. S2CID 4354549.

- ^ Nasmyth K, Haering CH (June 2005). "The structure and function of SMC and kleisin complexes". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 74 (1): 595–648. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133219. PMID 15952899.

- ^ a b Hauf S, Waizenegger IC, Peters JM (August 2001). "Cohesin cleavage by separase required for anaphase and cytokinesis in human cells". Science. 293 (5533): 1320–3. Bibcode:2001Sci...293.1320H. doi:10.1126/science.1061376. PMID 11509732. S2CID 46036132.

- ^ Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, et al. (October 2000). "Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast". Cell. 103 (3): 375–86. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00130-6. PMID 11081625. S2CID 2667617.

- ^ a b Panigrahi AK, Zhang N, Mao Q, et al. (November 2011). "Calpain-1 cleaves Rad21 to promote sister chromatid separation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 31 (21): 4335–47. doi:10.1128/MCB.06075-11. PMC 3209327. PMID 21876002.

- ^ a b c Chen F, Kamradt M, Mulcahy M, et al. (May 2002). "Caspase proteolysis of the cohesin component RAD21 promotes apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (19): 16775–81. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201322200. PMID 11875078.

- ^ a b c Pati D, Zhang N, Plon SE (December 2002). "Linking sister chromatid cohesion and apoptosis: role of Rad21". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (23): 8267–77. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.23.8267-8277.2002. PMC 134054. PMID 12417729.

- ^ Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, et al. (June 2009). "Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (25): 10171–6. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610171K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900604106. PMC 2695404. PMID 19520826.

- ^ a b Gligoris TG, Scheinost JC, Bürmann F, et al. (November 2014). "Closing the cohesin ring: structure and function of its Smc3-kleisin interface". Science. 346 (6212): 963–7. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..963G. doi:10.1126/science.1256917. PMC 4300515. PMID 25414305.

- ^ Haering CH, Löwe J, Hochwagen A, et al. (April 2002). "Molecular architecture of SMC proteins and the yeast cohesin complex". Molecular Cell. 9 (4): 773–88. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00515-4. PMID 11983169.

- ^ a b Zhang N, Kuznetsov SG, Sharan SK, et al. (December 2008). "A handcuff model for the cohesin complex". The Journal of Cell Biology. 183 (6): 1019–31. doi:10.1083/jcb.200801157. PMC 2600748. PMID 19075111.

- ^ Zhang N, Pati D (February 2009). "Handcuff for sisters: a new model for sister chromatid cohesion". Cell Cycle. 8 (3): 399–402. doi:10.4161/cc.8.3.7586. PMC 2689371. PMID 19177018.

- ^ Zhang N, Pati D (June 2012). "Sororin is a master regulator of sister chromatid cohesion and separation". Cell Cycle. 11 (11): 2073–83. doi:10.4161/cc.20241. PMC 3368859. PMID 22580470.

- ^ Nishiyama T, Ladurner R, Schmitz J, et al. (November 2010). "Sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion by antagonizing Wapl". Cell. 143 (5): 737–49. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.031. PMID 21111234. S2CID 518782.

- ^ a b Zhang N, Pati D (2014). "Road to cancer via cohesin deregulation.". Oncology: Theory & Practice. iConcept Press Hong Kong. pp. 213–240.

- ^ Hara K, Zheng G, Qu Q, et al. (October 2014). "Structure of cohesin subcomplex pinpoints direct shugoshin-Wapl antagonism in centromeric cohesion". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 21 (10): 864–70. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2880. PMC 4190070. PMID 25173175.

- ^ Petela NJ, Gligoris TG, Metson J, et al. (June 2018). "Scc2 Is a Potent Activator of Cohesin's ATPase that Promotes Loading by Binding Scc1 without Pds5". Molecular Cell. 70 (6): 1134–1148.e7. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.05.022. PMC 6028919. PMID 29932904.

- ^ Kikuchi S, Borek DM, Otwinowski Z, et al. (November 2016). "Crystal structure of the cohesin loader Scc2 and insight into cohesinopathy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (44): 12444–12449. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11312444K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611333113. PMC 5098657. PMID 27791135.

- ^ Muir KW, Kschonsak M, Li Y, et al. (March 2016). "Structure of the Pds5-Scc1 Complex and Implications for Cohesin Function". Cell Reports. 14 (9): 2116–2126. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.078. PMID 26923589.

- ^ Haering CH, Schoffnegger D, Nishino T, et al. (September 2004). "Structure and stability of cohesin's Smc1-kleisin interaction". Molecular Cell. 15 (6): 951–64. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.030. PMID 15383284.

- ^ Beckouët F, Srinivasan M, Roig MB, et al. (February 2016). "Releasing Activity Disengages Cohesin's Smc3/Scc1 Interface in a Process Blocked by Acetylation". Molecular Cell. 61 (4): 563–574. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.026. PMC 4769318. PMID 26895425.

- ^ Muir KW, Li Y, Weis F, et al. (March 2020). "The structure of the cohesin ATPase elucidates the mechanism of SMC-kleisin ring opening". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 27 (3): 233–239. doi:10.1038/s41594-020-0379-7. PMC 7100847. PMID 32066964.

- ^ "RAD21 cohesin complex component [Homo sapiens]". NCBI gene. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Panigrahi AK, Zhang N, Otta SK, et al. (March 2012). "A cohesin-RAD21 interactome". The Biochemical Journal. 442 (3): 661–70. doi:10.1042/BJ20111745. PMID 22145905. S2CID 46097282.

- ^ Gregson HC, Schmiesing JA, Kim JS, et al. (December 2001). "A potential role for human cohesin in mitotic spindle aster assembly". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (50): 47575–82. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103364200. PMID 11590136.

- ^ Guillou E, Ibarra A, Coulon V, et al. (December 2010). "Cohesin organizes chromatin loops at DNA replication factories". Genes & Development. 24 (24): 2812–22. doi:10.1101/gad.608210. PMC 3003199. PMID 21159821.

- ^ Takahashi TS, Yiu P, Chou MF, et al. (October 2004). "Recruitment of Xenopus Scc2 and cohesin to chromatin requires the pre-replication complex". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (10): 991–6. doi:10.1038/ncb1177. PMID 15448702. S2CID 20488928.

- ^ Ryu MJ, Kim BJ, Lee JW, et al. (March 2006). "Direct interaction between cohesin complex and DNA replication machinery". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 341 (3): 770–5. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.029. PMID 16438930.

- ^ Terret ME, Sherwood R, Rahman S, et al. (November 2009). "Cohesin acetylation speeds the replication fork". Nature. 462 (7270): 231–4. Bibcode:2009Natur.462..231T. doi:10.1038/nature08550. PMC 2777716. PMID 19907496.

- ^ MacAlpine HK, Gordân R, Powell SK, et al. (February 2010). "Drosophila ORC localizes to open chromatin and marks sites of cohesin complex loading". Genome Research. 20 (2): 201–11. doi:10.1101/gr.097873.109. PMC 2813476. PMID 19996087.

- ^ Unal E, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Koshland D (July 2007). "DNA double-strand breaks trigger genome-wide sister-chromatid cohesion through Eco1 (Ctf7)". Science. 317 (5835): 245–8. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..245U. doi:10.1126/science.1140637. PMID 17626885. S2CID 551399.

- ^ Heidinger-Pauli JM, Unal E, Koshland D (May 2009). "Distinct targets of the Eco1 acetyltransferase modulate cohesion in S phase and in response to DNA damage". Molecular Cell. 34 (3): 311–21. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.008. PMC 2737744. PMID 19450529.

- ^ Ström L, Lindroos HB, Shirahige K, et al. (December 2004). "Postreplicative recruitment of cohesin to double-strand breaks is required for DNA repair". Molecular Cell. 16 (6): 1003–15. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.026. PMID 15610742.

- ^ Kim BJ, Li Y, Zhang J, et al. (July 2010). "Genome-wide reinforcement of cohesin binding at pre-existing cohesin sites in response to ionizing radiation in human cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (30): 22784–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.134577. PMC 2906269. PMID 20501661.

- ^ Watrin E, Peters JM (September 2009). "The cohesin complex is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint in mammalian cells". The EMBO Journal. 28 (17): 2625–35. doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.202. PMC 2738698. PMID 19629043.

- ^ Cortés-Ledesma F, Aguilera A (September 2006). "Double-strand breaks arising by replication through a nick are repaired by cohesin-dependent sister-chromatid exchange". EMBO Reports. 7 (9): 919–26. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400774. PMC 1559660. PMID 16888651.

- ^ Watrin E, Peters JM (August 2006). "Cohesin and DNA damage repair". Experimental Cell Research. 312 (14): 2687–93. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.024. PMID 16876157.

- ^ Ball AR, Yokomori K (January 2008). "Damage-induced reactivation of cohesin in postreplicative DNA repair". BioEssays. 30 (1): 5–9. doi:10.1002/bies.20691. PMC 4127326. PMID 18081005.

- ^ Sjögren C, Ström L (May 2010). "S-phase and DNA damage activated establishment of sister chromatid cohesion--importance for DNA repair". Experimental Cell Research. 316 (9): 1445–53. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.12.018. PMID 20043905.

- ^ a b c Wendt KS, Yoshida K, Itoh T, et al. (February 2008). "Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor". Nature. 451 (7180): 796–801. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..796W. doi:10.1038/nature06634. PMID 18235444. S2CID 205212289.

- ^ a b Skibbens RV, Marzillier J, Eastman L (April 2010). "Cohesins coordinate gene transcriptions of related function within Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Cell Cycle. 9 (8): 1601–6. doi:10.4161/cc.9.8.11307. PMC 3096706. PMID 20404480.

- ^ a b c Schmidt D, Schwalie PC, Ross-Innes CS, et al. (May 2010). "A CTCF-independent role for cohesin in tissue-specific transcription". Genome Research. 20 (5): 578–88. doi:10.1101/gr.100479.109. PMC 2860160. PMID 20219941.

- ^ a b Kagey MH, Newman JJ, Bilodeau S, et al. (September 2010). "Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture". Nature. 467 (7314): 430–5. Bibcode:2010Natur.467..430K. doi:10.1038/nature09380. PMC 2953795. PMID 20720539.

- ^ Pauli A, van Bemmel JG, Oliveira RA, et al. (October 2010). "A direct role for cohesin in gene regulation and ecdysone response in Drosophila salivary glands". Current Biology. 20 (20): 1787–98. Bibcode:2010CBio...20.1787P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.006. PMC 4763543. PMID 20933422.

- ^ Dorsett D (October 2010). "Gene regulation: the cohesin ring connects developmental highways". Current Biology. 20 (20): R886-8. Bibcode:2010CBio...20.R886D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.036. PMID 20971431. S2CID 2543711.

- ^ a b Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, et al. (February 2008). "Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms". Cell. 132 (3): 422–33. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. PMID 18237772. S2CID 14363394.

- ^ Liu J, Zhang Z, Bando M, et al. (May 2009). Hastie N (ed.). "Transcriptional dysregulation in NIPBL and cohesin mutant human cells". PLOS Biology. 7 (5): e1000119. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000119. PMC 2680332. PMID 19468298.

- ^ a b Mazumdar C, Shen Y, Xavy S, et al. (December 2015). "Leukemia-Associated Cohesin Mutants Dominantly Enforce Stem Cell Programs and Impair Human Hematopoietic Progenitor Differentiation". Cell Stem Cell. 17 (6): 675–688. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2015.09.017. PMC 4671831. PMID 26607380.

- ^ a b Mullenders J, Aranda-Orgilles B, Lhoumaud P, et al. (October 2015). "Cohesin loss alters adult hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis, leading to myeloproliferative neoplasms". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 212 (11): 1833–50. doi:10.1084/jem.20151323. PMC 4612095. PMID 26438359.

- ^ Viny AD, Ott CJ, Spitzer B, et al. (October 2015). "Dose-dependent role of the cohesin complex in normal and malignant hematopoiesis". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 212 (11): 1819–32. doi:10.1084/jem.20151317. PMC 4612085. PMID 26438361.

- ^ Fisher JB, McNulty M, Burke MJ, et al. (April 2017). "Cohesin Mutations in Myeloid Malignancies". Trends in Cancer. 3 (4): 282–293. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2017.02.006. PMC 5472227. PMID 28626802.

- ^ Rao S (December 2019). "Closing the loop on cohesin in hematopoiesis". Blood. 134 (24): 2123–2125. doi:10.1182/blood.2019003279. PMC 6908834. PMID 31830276.

- ^ Degner SC, Verma-Gaur J, Wong TP, et al. (June 2011). "CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin influence the genomic architecture of the Igh locus and antisense transcription in pro-B cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (23): 9566–71. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.9566D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019391108. PMC 3111298. PMID 21606361.

- ^ a b Guo Y, Monahan K, Wu H, et al. (December 2012). "CTCF/cohesin-mediated DNA looping is required for protocadherin α promoter choice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (51): 21081–6. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10921081G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219280110. PMC 3529044. PMID 23204437.

- ^ Hadjur S, Williams LM, Ryan NK, et al. (July 2009). "Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus". Nature. 460 (7253): 410–3. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..410H. doi:10.1038/nature08079. PMC 2869028. PMID 19458616.

- ^ Faure AJ, Schmidt D, Watt S, et al. (November 2012). "Cohesin regulates tissue-specific expression by stabilizing highly occupied cis-regulatory modules". Genome Research. 22 (11): 2163–75. doi:10.1101/gr.136507.111. PMC 3483546. PMID 22780989.

- ^ Seitan VC, Hao B, Tachibana-Konwalski K, et al. (August 2011). "A role for cohesin in T-cell-receptor rearrangement and thymocyte differentiation". Nature. 476 (7361): 467–71. Bibcode:2011Natur.476..467S. doi:10.1038/nature10312. PMC 3179485. PMID 21832993.

- ^ a b Yan J, Enge M, Whitington T, et al. (August 2013). "Transcription factor binding in human cells occurs in dense clusters formed around cohesin anchor sites". Cell. 154 (4): 801–13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.034. PMID 23953112.

- ^ a b Zhang H, Jiao W, Sun L, et al. (July 2013). "Intrachromosomal looping is required for activation of endogenous pluripotency genes during reprogramming". Cell Stem Cell. 13 (1): 30–5. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.012. PMID 23747202.

- ^ Fay A, Misulovin Z, Li J, et al. (October 2011). "Cohesin selectively binds and regulates genes with paused RNA polymerase". Current Biology. 21 (19): 1624–34. Bibcode:2011CBio...21.1624F. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.036. PMC 3193539. PMID 21962715.

- ^ Schaaf CA, Kwak H, Koenig A, et al. (March 2013). Ren B (ed.). "Genome-wide control of RNA polymerase II activity by cohesin". PLOS Genetics. 9 (3): e1003382. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003382. PMC 3605059. PMID 23555293.

- ^ Rubio ED, Reiss DJ, Welcsh PL, et al. (June 2008). "CTCF physically links cohesin to chromatin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (24): 8309–14. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.8309R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801273105. PMC 2448833. PMID 18550811.

- ^ Dorsett D, Merkenschlager M (June 2013). "Cohesin at active genes: a unifying theme for cohesin and gene expression from model organisms to humans". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 25 (3): 327–33. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2013.02.003. PMC 3691354. PMID 23465542.

- ^ a b Leeke B, Marsman J, O'Sullivan JM, et al. (2014). "Cohesin mutations in myeloid malignancies: underlying mechanisms". Experimental Hematology & Oncology. 3 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/2162-3619-3-13. PMC 4046106. PMID 24904756.

- ^ Tachibana-Konwalski K, Godwin J, van der Weyden L, et al. (November 2010). "Rec8-containing cohesin maintains bivalents without turnover during the growing phase of mouse oocytes". Genes & Development. 24 (22): 2505–16. doi:10.1101/gad.605910. PMC 2975927. PMID 20971813.

- ^ Buonomo SB, Clyne RK, Fuchs J, et al. (October 2000). "Disjunction of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I depends on proteolytic cleavage of the meiotic cohesin Rec8 by separin". Cell. 103 (3): 387–98. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00131-8. PMID 11081626. S2CID 17385055.

- ^ a b Lee J, Hirano T (January 2011). "RAD21L, a novel cohesin subunit implicated in linking homologous chromosomes in mammalian meiosis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 192 (2): 263–76. doi:10.1083/jcb.201008005. PMC 3172173. PMID 21242291.

- ^ Ishiguro K, Kim J, Fujiyama-Nakamura S, et al. (March 2011). "A new meiosis-specific cohesin complex implicated in the cohesin code for homologous pairing". EMBO Reports. 12 (3): 267–75. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.2. PMC 3059921. PMID 21274006.

- ^ Krab LC, Marcos-Alcalde I, Assaf M, et al. (May 2020). "Delineation of phenotypes and genotypes related to cohesin structural protein RAD21". Human Genetics. 139 (5): 575–592. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02138-2. PMC 7170815. PMID 32193685.

- ^ Deardorff MA, Wilde JJ, Albrecht M, et al. (June 2012). "RAD21 mutations cause a human cohesinopathy". American Journal of Human Genetics. 90 (6): 1014–27. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.019. PMC 3370273. PMID 22633399.

- ^ Ansari M, Poke G, Ferry Q, et al. (October 2014). "Genetic heterogeneity in Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) and CdLS-like phenotypes with observed and predicted levels of mosaicism". Journal of Medical Genetics. 51 (10): 659–68. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102573. PMC 4173748. PMID 25125236.

- ^ Minor A, Shinawi M, Hogue JS, et al. (March 2014). "Two novel RAD21 mutations in patients with mild Cornelia de Lange syndrome-like presentation and report of the first familial case". Gene. 537 (2): 279–84. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.12.045. PMID 24378232.

- ^ Boyle MI, Jespersgaard C, Nazaryan L, et al. (April 2017). "A novel RAD21 variant associated with intrafamilial phenotypic variation in Cornelia de Lange syndrome - review of the literature". Clinical Genetics. 91 (4): 647–649. doi:10.1111/cge.12863. PMID 27882533. S2CID 3732288.

- ^ Martínez F, Caro-Llopis A, Roselló M, et al. (February 2017). "High diagnostic yield of syndromic intellectual disability by targeted next-generation sequencing". Journal of Medical Genetics. 54 (2): 87–92. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103964. PMID 27620904. S2CID 46740644.

- ^ Dorval S, Masciadri M, Mathot M, et al. (January 2020). "A novel RAD21 mutation in a boy with mild Cornelia de Lange presentation: Further delineation of the phenotype". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 63 (1): 103620. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.01.010. PMID 30716475. S2CID 73443712.

- ^ Gudmundsson S, Annerén G, Marcos-Alcalde Í, et al. (June 2019). "A novel RAD21 p.(Gln592del) variant expands the clinical description of Cornelia de Lange syndrome type 4 - Review of the literature". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 62 (6): 103526. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.08.007. hdl:10641/1986. PMID 30125677. S2CID 52046223.

- ^ Pereza N, Severinski S, Ostojić S, et al. (June 2015). "Cornelia de Lange syndrome caused by heterozygous deletions of chromosome 8q24: comments on the article by Pereza et al. [2012]". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 167 (6): 1426–7. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36974. PMID 25899858. S2CID 205320077.

- ^ Wuyts W, Roland D, Lüdecke HJ, et al. (December 2002). "Multiple exostoses, mental retardation, hypertrichosis, and brain abnormalities in a boy with a de novo 8q24 submicroscopic interstitial deletion". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 113 (4): 326–32. doi:10.1002/ajmg.10845. PMID 12457403.

- ^ McBrien J, Crolla JA, Huang S, et al. (June 2008). "Further case of microdeletion of 8q24 with phenotype overlapping Langer-Giedion without TRPS1 deletion". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 146A (12): 1587–92. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32347. PMID 18478595. S2CID 19384557.

- ^ Bonora E, Bianco F, Cordeddu L, et al. (April 2015). "Mutations in RAD21 disrupt regulation of APOB in patients with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction". Gastroenterology. 148 (4): 771–782.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.034. hdl:11693/23636. PMC 4375026. PMID 25575569.

- ^ Mungan Z, Akyüz F, Bugra Z, et al. (November 2003). "Familial visceral myopathy with pseudo-obstruction, megaduodenum, Barrett's esophagus, and cardiac abnormalities". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 98 (11): 2556–60. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08707.x. PMID 14638363. S2CID 21022551.

- ^ Mintzas K, Heuser M (June 2019). "Emerging strategies to target the dysfunctional cohesin complex in cancer". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 23 (6): 525–537. doi:10.1080/14728222.2019.1609943. PMID 31020869. S2CID 131776323.

- ^ van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, et al. (January 2002). "Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer". Nature. 415 (6871): 530–6. doi:10.1038/415530a. hdl:1874/15552. PMID 11823860. S2CID 4369266.

- ^ Xu H, Yan M, Patra J, et al. (January 2011). "Enhanced RAD21 cohesin expression confers poor prognosis and resistance to chemotherapy in high grade luminal, basal and HER2 breast cancers". Breast Cancer Research. 13 (1): R9. doi:10.1186/bcr2814. PMC 3109576. PMID 21255398.

- ^ Yamamoto G, Irie T, Aida T, et al. (April 2006). "Correlation of invasion and metastasis of cancer cells, and expression of the RAD21 gene in oral squamous cell carcinoma". Virchows Archiv. 448 (4): 435–41. doi:10.1007/s00428-005-0132-y. PMID 16416296. S2CID 22993345.

- ^ Deb S, Xu H, Tuynman J, et al. (March 2014). "RAD21 cohesin overexpression is a prognostic and predictive marker exacerbating poor prognosis in KRAS mutant colorectal carcinomas". British Journal of Cancer. 110 (6): 1606–13. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.31. PMC 3960611. PMID 24548858.

- ^ Porkka KP, Tammela TL, Vessella RL, et al. (January 2004). "RAD21 and KIAA0196 at 8q24 are amplified and overexpressed in prostate cancer". Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 39 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1002/gcc.10289. PMID 14603436. S2CID 46570803.

- ^ Yun J, Song SH, Kang JY, et al. (January 2016). "Reduced cohesin destabilizes high-level gene amplification by disrupting pre-replication complex bindings in human cancers with chromosomal instability". Nucleic Acids Research. 44 (2): 558–72. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv933. PMC 4737181. PMID 26420833.

- ^ Fisher JB, Peterson J, Reimer M, et al. (March 2017). "The cohesin subunit Rad21 is a negative regulator of hematopoietic self-renewal through epigenetic repression of Hoxa7 and Hoxa9". Leukemia. 31 (3): 712–719. doi:10.1038/leu.2016.240. PMC 5332284. PMID 27554164.

- ^ Solomon DA, Kim JS, Waldman T (June 2014). "Cohesin gene mutations in tumorigenesis: from discovery to clinical significance". BMB Reports. 47 (6): 299–310. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2014.47.6.092. PMC 4163871. PMID 24856830.

- ^ Thota S, Viny AD, Makishima H, et al. (September 2014). "Genetic alterations of the cohesin complex genes in myeloid malignancies". Blood. 124 (11): 1790–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-04-567057. PMC 4162108. PMID 25006131.

- ^ Hill VK, Kim JS, Waldman T (August 2016). "Cohesin mutations in human cancer". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1866 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.05.002. PMC 4980180. PMID 27207471.

- ^ Corces-Zimmerman MR, Hong WJ, Weissman IL, et al. (February 2014). "Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (7): 2548–53. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.2548C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1324297111. PMC 3932921. PMID 24550281.

- ^ Ley TJ, Miller C, Ding L, et al. (May 2013). "Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (22): 2059–74. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. PMC 3767041. PMID 23634996.

- ^ Kon A, Shih LY, Minamino M, et al. (October 2013). "Recurrent mutations in multiple components of the cohesin complex in myeloid neoplasms". Nature Genetics. 45 (10): 1232–7. doi:10.1038/ng.2731. PMID 23955599. S2CID 12395243.

- ^ Thol F, Bollin R, Gehlhaar M, et al. (February 2014). "Mutations in the cohesin complex in acute myeloid leukemia: clinical and prognostic implications". Blood. 123 (6): 914–20. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-07-518746. PMID 24335498. S2CID 206923475.

- ^ Lindsley RC, Mar BG, Mazzola E, et al. (February 2015). "Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations". Blood. 125 (9): 1367–76. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-610543. PMC 4342352. PMID 25550361.

- ^ Tsai CH, Hou HA, Tang JL, et al. (December 2017). "Prognostic impacts and dynamic changes of cohesin complex gene mutations in de novo acute myeloid leukemia". Blood Cancer Journal. 7 (12): 663. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0022-y. PMC 5802563. PMID 29288251.

- ^ Eisfeld AK, Kohlschmidt J, Mrózek K, et al. (June 2018). "Mutation patterns identify adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia aged 60 years or older who respond favorably to standard chemotherapy: an analysis of Alliance studies". Leukemia. 32 (6): 1338–1348. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0068-2. PMC 5992022. PMID 29563537.

- ^ Weinberg OK, Gibson CJ, Blonquist TM, et al. (April 2018). "de novo acute myeloid leukemia without 2016 WHO Classification-defined cytogenetic abnormalities". Haematologica. 103 (4): 626–633. doi:10.3324/haematol.2017.181842. PMC 5865424. PMID 29326119.

- ^ Duployez N, Marceau-Renaut A, Boissel N, et al. (May 2016). "Comprehensive mutational profiling of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia". Blood. 127 (20): 2451–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-12-688705. PMC 5457131. PMID 26980726.

- ^ Yoshida K, Toki T, Okuno Y, et al. (November 2013). "The landscape of somatic mutations in Down syndrome-related myeloid disorders". Nature Genetics. 45 (11): 1293–9. doi:10.1038/ng.2759. PMID 24056718. S2CID 32383374.