Pseudogout

| Pseudogout | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease; calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease; CPP crystal arthritis;[1] calcium gout[2] | |

| |

| Polarized light microscopy of CPPD, showing rhombus-shaped calcium pyrophosphate crystals with positive birefringence. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Pain, redness, swelling, and heat in one or a few joints[1] |

| Complications | Osteoarthritis[3] |

| Usual onset | Older people[2] |

| Causes | Often unclear; genetic[4] |

| Risk factors | Joint injury, hypophosphatasia, hemochromatosis, high parathyroid hormone[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Joint aspiration, medical imaging[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Septic arthritis, gout[1] |

| Treatment | Colchicine, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, anakinra[3][5] |

| Prognosis | Attacks last weeks to months despite treatment[1][3] |

| Frequency | 5%[1] |

Pseudogout, also known as calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD), is joint inflammation due to calcium pyrophosphate crystals.[1] Attacks typically present as sudden onset of pain in one or a few joints.[1] There is generally also redness, swelling, and heat present.[1] The knee joint followed by the wrist are most commonly affected.[1] Generally the big toe is not affected.[1] Other symptoms may include fever.[1] Complications may include osteoarthritis.[3]

The cause of the crystals in most cases is unclear; though it occasionally it runs in families.[1][4] Risk factors include previous joint injury.[1] It is associated with hypophosphatasia, hemochromatosis, and high parathyroid hormone.[1][2] Diet does not affect risk.[1] Diagnosis may be confirmed by finding crystals that are rhomboid shaped and birefringent with polarized light in joint fluid.[2] Medical imaging may show calcification of cartilage.[3]

Attacks may be treated with colchicine, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, or anakinra.[3][5] Evidence for preventative measures is poor; though, may include hydroxychloroquine or methotrexate.[6][3] Symptoms of an attack may continue for weeks or months even with treatment.[1][3]

Pseudogout affects about 5% of people in the United States and Europe.[1] It is more common in older people, typically over the age of 60.[1][3] The condition occurs with similar frequency in males and females; though, males may have more attacks.[7] The initial descriptions of the condition is from 1962 by N. Kohn.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The disease classically begins with symptoms similar to a gout attack. These include:

- severe joint pain

- warmth

- swelling of one or more joints

The symptoms may involve a single joint or several joints.[8] Symptoms usually last for days to weeks, and often recur. Although any joint may be affected, the knees, wrists, and hips are most common.[9]

Cause

The cause of CPPD disease is unknown. Increased breakdown of adenosine triphosphate (ATP; the molecule used as energy currency in all living things), which results in increased pyrophosphate levels in joints, is thought to be one reason why crystals may develop.[9]

Familial forms are rare.[10] One genetic study found an association between CPPD and a region of chromosome 8q.[11]

The gene ANKH is involved in crystal-related inflammatory reactions and inorganic phosphate transport.[12][9]

Diagnosis

The disease is defined by the presence of joint inflammation and CPPD crystals within the joint. The crystals are usually detected by imaging or joint fluid analysis. X-ray, CT, or other imaging usually shows accumulation of calcium within the joint cartilage, known as chondrocalcinosis. There can also be findings of osteoarthritis.[12][9] The white blood cell count is often raised.[9]

Medical imaging, consisting of x-ray, CT, MRI, or ultrasound may detect chondrocalcinosis within the affected joint, indicating a substantial amount of calcium crystal deposition within the cartilage or ligaments.[13] Ultrasound is a reliable method to diagnose CPPD.[14] Using ultrasound, chondrocalcinosis may be depicted as echogenic foci with no acoustic shadow within the hyaline cartilage[15] or fibrocartilage.[14] By x-ray, CPPD can appear similar to other diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis and gout.[13][9]

Arthrocentesis, or removing synovial fluid from the affected joint, is performed to test the synovial fluid for the calcium pyrophosphate crystals that are present in CPPD. When stained with H&E stain, calcium pyrophosphate crystals appears deeply blue ("basophilic").[16][17] However, CPP crystals are much better known for their rhomboid shape and weak positive birefringence on polarized light microscopy, and this method remains the most reliable method of identifying the crystals under the microscope.[18] However, even this method has poor sensitivity, specificity, and inter-operator agreement.[18]

These two modalities currently define CPPD disease, but lack diagnostic accuracy.[19] Thus, the diagnosis of CPPD disease is potentially epiphenomenological.

-

X-ray of a knee with chondrocalcinosis.

-

Micrograph showing crystal deposition in an intervertebral disc. H&E stain.

-

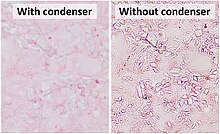

CPPD crystals are more clearly visualized on light microscopy without a condenser.

Treatment

Because any medication that could reduce the inflammation of CPPD bears a risk of causing organ damage, treatment is not advised if the condition is not causing pain.[9] For acute pseudogout, treatments include intra-articular corticosteroid injection, systemic corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or, on occasion, high-dose colchicine.[9] In general, NSAIDs are administered in low doses to help prevent CPPD. However, if an acute attack is already occurring, higher doses are administered.[9] If nothing else works, hydroxychloroquine or methotrexate may provide relief.[20] Research into surgical removal of calcifications is underway, however, this still remains an experimental procedure.[9]

Epidemiology

The condition is more common in older adults.[12]

CPPD is estimated to affect 4% to 7% of the adult populations of Europe and the United States.[21] Previous studies have overestimated the prevalence by simply estimating the prevalence of chondrocalcinosis, which is found in many other conditions as well.[21]

It may cause considerable pain, but it is never fatal.[9] Women are at a slightly higher risk than men, with an estimated ratio of occurrence of 1.4:1.[9]

History

CPPD crystal deposition disease was originally described over 50 years ago.[19]

Terminology

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals are associated with a range of clinical syndromes, which have been given various names, based upon which clinical symptoms or radiographic findings are most prominent.[19] A task force of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) made recommendations on preferred terminology.[10] Accordingly, calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) is an umbrella term for the various clinical subsets, whose naming reflects an emphasis on particular features. For example, pseudogout refers to the acute symptoms of joint inflammation or synovitis: red, tender, and swollen joints that may resemble gouty arthritis (a similar condition in which monosodium urate crystals are deposited within the joints). Chondrocalcinosis,[13][9] on the other hand, refers to the radiographic evidence of calcification in hyaline and/or fibrocartilage. "Osteoarthritis (OA) with CPPD" reflects a situation where osteoarthritis features are the most apparent. Pyrophosphate arthropathy refers to several of these situations.[22]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Rosenthal, AK; Ryan, LM (30 June 2016). "Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease". The New England journal of medicine. 374 (26): 2575–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511117. PMID 27355536.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "14. Cutaneous deposits". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Cowley, S; McCarthy, G (2023). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition (CPPD) Disease: A Review". Open access rheumatology : research and reviews. 15: 33–41. doi:10.2147/OARRR.S389664. PMID 36987530.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Pseudogout: Symptoms and Treatment | The Hand Society". www.assh.org. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Aouba, A; Deshayes, S; Frenzel, L; Decottignies, A; Pressiat, C; Bienvenu, B; Boue, F; Damaj, G; Hermine, O; Georgin-Lavialle, S (2015). "Efficacy of anakinra for various types of crystal-induced arthritis in complex hospitalized patients: a case series and review of the literature". Mediators of inflammation. 2015: 792173. doi:10.1155/2015/792173. PMID 25922564.

- ↑ Sidari, A; Hill, E (June 2018). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Gout and Pseudogout for Everyday Practice". Primary care. 45 (2): 213–236. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.004. PMID 29759121.

- ↑ Macmullan, P; McCarthy, G (April 2012). "Treatment and management of pseudogout: insights for the clinician". Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease. 4 (2): 121–31. doi:10.1177/1759720X11432559. PMID 22870500.

- ↑ Wright GD, Doherty M (1997). "Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition is not always 'wear and tear' or aging". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 56 (10): 586–8. doi:10.1136/ard.56.10.586. PMC 1752269. PMID 9389218.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Rothschild, Bruce M Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease (rheumatology) at eMedicine

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Barskova V, Guerne PA, Jansen TL, Leeb BF, Perez-Ruiz F, Pimentao J, Punzi L, Richette P, Sivera F, Uhlig T, Watt I, Pascual E. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Part I: terminology and diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(4):563.

- ↑ Baldwin CT, Farrer LA, Adair R, Dharmavaram R, Jimenez S, Anderson L (March 1995). "Linkage of early-onset osteoarthritis and chondrocalcinosis to human chromosome 8q". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 56 (3): 692–7. PMC 1801178. PMID 7887424.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Tsui FW (Apr 2012). "Genetics and mechanisms of crystal deposition in calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease". Curr Rheumatol Rep. 14 (2): 155–60. doi:10.1007/s11926-011-0230-6. PMID 22198832. S2CID 41336263.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Rothschild, Bruce M Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease (radiology)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Filippou, G.; Adinolfi, A.; Iagnocco, A.; Filippucci, E.; Cimmino, M.A.; Bertoldi, I.; Di Sabatino, V.; Picerno, V.; Delle Sedie, A.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Frediani, B. (June 2016). "Ultrasound in the diagnosis of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease. A systematic literature review and a meta-analysis". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 24 (6): 973–981. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2016.01.136. PMID 26826301.

- ↑ Arend CF. Ultrasound of the Shoulder. Master Medical Books, 2013. Free chapter on acromioclavicular chondrocalcinosis is available at ShoulderUS.com Archived 2017-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hosler, Greg. "calcinosis_cutis_2_060122". Derm Atlas. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ↑ "Calcium Pyrophosphate Dihydrate Deposition Disease: Synovial Biopsy, Wrist". Rheumatology Image Bank. American College of Rheumatology. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Dieppe, P.; Swan, A. (1 May 1999). "Identification of crystals in synovial fluid". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 58 (5): 261–3. doi:10.1136/ard.58.5.261. PMC 1752883. PMID 10225806.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Rosenthal, AK; Ryan, LM (May 2011). "Crystal arthritis: Calcium pyrophosphate deposition—nothing 'pseudo' about it!". Nat Rev Rheumatol. 7 (5): 257–8. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2011.50. PMID 21532639.

- ↑ Emkey GR, Reginato AM (2009). "All about gout and pseudogout". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 26 (10). Archived from the original on 2022-09-27. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Ann K. Rosenthal. "Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition (CPPD) disease". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 2019-04-07. Retrieved 2022-08-04. This topic last updated: Jul 24, 2018.

- ↑ Longmore, Murray; Ian Wilkinson; Tom Turmezei; Chee Kay Cheung (2007). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford. p. 841. ISBN 978-0-19-856837-7.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |