Prostate brachytherapy

| Prostate brachytherapy | |

|---|---|

Figure 1. Single and stranded brachytherapy seeds showing relative sizes of the seeds and needles used for insertion | |

| ICD-9-CM | 92.27 |

| MedlinePlus | 007385 |

Brachytherapy is a type of radiotherapy, or radiation treatment, offered to certain cancer patients. There are two types of brachytherapy – high dose-rate (HDR) and low dose-rate (LDR). LDR brachytherapy is the one most commonly used to treat prostate cancer. It may be referred to as 'seed implantation' or it may be called 'pinhole surgery'.[1]

In LDR brachytherapy, tiny radioactive particles the size of a grain of rice (Figure 1) are implanted directly into, or very close to, the tumour. These particles are known as 'seeds', and they can be inserted linked together as strands, or individually. The seeds deliver high doses of radiation to the tumour without affecting the normal healthy tissues around it. The procedure is less damaging than conventional radiation therapy, where the radioactive beam is delivered from outside the body and must pass through other tissues before reaching the tumour.[2]

In addition to seeds, a newer polymer-encapsulated LDR source is available. The source features 103Pd along the full length of the device which is contained using low-Z polymers. The polymer construction and linear radioactive distribution of this source creates a very homogenous dose distribution.[3]

LDR prostate brachytherapy (seed or line source implantation) is a proven treatment for low to high risk localized prostate cancer (when the cancer is contained within the prostate).[4][5] Under a general anaesthetic, the radioactive seeds are injected through fine needles directly into the prostate, so that the radiotherapy can destroy the cancer cells. The seeds are permanently implanted. They remain in place but gradually become inactive as the radioactivity decays naturally and safely over time.[6] Unlike traditional surgery, LDR brachytherapy requires no incisions and is normally carried out as an outpatient (day case) procedure. Sometimes a single overnight stay in hospital is required. Patients usually recover quickly from LDR brachytherapy. Most men can return to work or normal daily activities within a few days. LDR brachytherapy has fewer side-effects with less risk of incontinence or impotence than other treatment options.[7] It is a popular alternative to major surgery (conventional radical prostatectomy or laparoscopic (keyhole surgery) radical prostatectomy).[citation needed]

Isotopes used include iodine 125 (half-life 59.4 days) palladium 103 (half-life 17 days) and cesium-131 (half life 9.7 days).[8]

Procedure

When LDR prostate brachytherapy (seed or polymer source implantation) is carried out, an ultrasound probe is inserted into the rectum (back passage), and images from this probe are used to assess the size and shape of the prostate gland. This is done so that the doctor can identify how to best deliver the right radiation dose for each patient. Then the seeds are inserted in the exact locations identified at the beginning of the procedure. This usually takes 1–2 hours.[9] No surgical incision is required; instead, the radioactive seeds are inserted into the prostate gland using needles which pass through the skin between the scrotum and the rectum (the perineum) and an ultrasound probe is used to accurately guide them to their final position. The needles are put into the target positions and between 70 and 150 seeds are placed into the prostate. The needles are then removed. {•figure•} shows the grid-like device used to guide the needles into the perineal area; co-ordinates or 'map references' on this grid or template are used to pinpoint the exact positions in the prostate where the seeds are to be placed. Figure 3 shows how the seeds are positioned to target the tumour. The doctor uses ultrasound and X-ray pictures to make sure the seeds are in the right place. A special computer software program is used to make sure the prostate gland is completely covered by just the right dose of radiation (see Figure 4) to ensure that all cancer cells present in the prostate have been completely treated.[citation needed]

Once in place, the seeds or sources slowly begin to release their radiation. While the sources are active, the patient must observe some basic precautions. Travel and contact with adults are fine; however, for the first two months following seed implantation, small children and pregnant women should not be in direct contact with the patient for prolonged periods – for example children should not sit on the patient's knee for any length of time. Sexual intercourse can start again within a few weeks. Very occasionally a seed can be expelled in the semen on ejaculation; if this does happen, it will usually occur in the first few ejaculations, so it is advisable to use a condom for the first two or three occasions of intercourse following LDR brachytherapy.[10]

Patients can usually return to normal activities and work within a few days. They should expect to be seen for follow-up after four to six weeks, and then every three months for a year, six-monthly up to five years, then annually.[9][10]

Indications

LDR prostate brachytherapy (seed or polymer source implantation) is recommended as a treatment for patients whose cancer is at an early stage (cancer stages T1 to T2), and which has not spread beyond the prostate (localised disease).[10][11] Doctors use a combination of factors such as cancer stage and grade, PSA level, Gleason score and urine flow/bladder emptying tests to help them decide if a patient is suitable for LDR brachytherapy. Patients should ask their doctors about the results of these different tests and how they influence the type of treatment they may be offered.[10][11] LDR brachytherapy in combination with external beam radiotherapy may also be recommended for patients with later-stage cancer and higher PSA level and Gleason score.[10]

Risks and benefits

Since its introduction in the mid-1980s, prostate brachytherapy has become a well-established treatment option for patients with early, localised disease. In the US, over 50,000 eligible prostate cancer patients a year are treated using this method.[12] Brachytherapy is now in widespread use across the world. In the UK, prostate brachytherapy is provided at a majority of cancer centres and thousands of patients have been treated.[13]

Clinical benefits

LDR prostate brachytherapy on its own has been shown to be highly effective for the treatment of early prostate cancer.[14] The rate of survival with no increase in average PSA levels after LDR brachytherapy is similar to that achieved with external beam radiotherapy and radical prostatectomy.[4] However LDR brachytherapy has a lower risk of some of the complications associated with other treatment options.[7]

Side-effects

LDR prostate brachytherapy (seed or polymer source implantation) is a very effective treatment for low to high risk localized cancer, with patients rapidly returning to normal activities.[15] Although patients may experience urinary problems for the first six months or so after their implant, these usually settle down and lasting problems are rare, only occurring in about 1–2% of patients.[16] The complications include:

- Urinary problems may include urinary incontinence, mainly stress incontinence or urge incontinence, difficulty with urination, and urinary retention. According to a review published in 2002,[17] on the long term, significant obstructive symptoms or persistent urinary retention requiring TURP occurred in 0–8.7% of patients. Urinary incontinence was found in up to 19% of patients treated by implant who had not had a previous TURP, however, the percentage was a lot higher in those who did (up to 86%). The stress incontinence can be regarded as a result of direct damage to the external urethral sphincter that results from the radiation. Treatment may include lifestyle changes, bladder training, and the use of incontinence pads. Surgical treatment in those who fail initial therapy can include the use of a urethral sling or an artificial urinary sphincter. [citation needed]

- Bowel problems. Some patients (less than 10%) report an increase in bowel problems (diarrhea or urgency of the bowels), but again this usually settles down without further treatment.[18] Radiation proctitis can be found in 0.5–21.4% of patients who received prostate brachytherapy due to the proximity of the prostate and the large bowel, with significant injury (fistula) occurring in 1–2.4% of patients.[citation needed]

- Erectile dysfunction (difficulty getting and/or keeping an erection; impotence) is another side-effect associated with some surgical and non surgical treatments of prostate cancer. The problem ranges from 25 to 50% of men who receive prostate brachytherapy, which is less than that observed in men receiving standard external beam radiation.[19] Within three years, not many men will see significant improvement in potency, and occasionally the numbers may worsen.[19] Treatment options include the use of medications (such as Viagra and Cialis), intracavernous injectables, vacuum constriction device, or penile implants.[19]

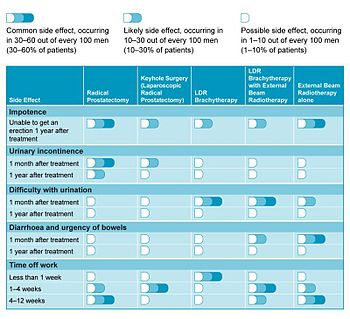

In a 2006 study looking at patients' quality of life, LDR brachytherapy compared favourably with other treatment options.[18] Table 1 summarises the more common side-effects related with each form of treatment and how these may affect patient recovery.

See also

References

- ^ Skowronek, Janusz (2013). "Low-dose-rate or high-dose-rate brachytherapy in treatment of prostate cancer – between options". Journal of Contemporary Brachytherapy. 5 (1): 33–41. doi:10.5114/jcb.2013.34342. PMC 3635047. PMID 23634153.

- ^ Van Limbergen, Erik; Joiner, Michael; Van der Kogel, Albert; Dörr, Wolfgang. "Radiobiology of LDR, HDR, PDR and VLDR Brachytherapy". In Van Limbergen, Erik; Pötter, Richard; Hoskin, Peter; Baltas, Dimos (eds.). GEC-ESTRO Handbook of Brachytherapy. Brussels: ESTRO.

- ^ Rivard, Mark J.; Reed, Joshua L.; DeWerd, Larry A. (2014-01-01). "103Pd strings: Monte Carlo assessment of a new approach to brachytherapy source design". Medical Physics. 41 (1): 011716. Bibcode:2014MedPh..41a1716R. doi:10.1118/1.4856015. ISSN 0094-2405. PMID 24387508.

- ^ a b Kupelian PA, Potters L, Khuntia D, et al. (2004). "Radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy less than 72 Gy, external beam radiotherapy ≥72 Gy, permanent seed implantation, or combined seeds/external beam radiotherapy for stage T1-T2 prostate cancer". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 58 (1): 25–33. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00784-3. PMID 14697417.

- ^ Potters L, Morgenstern C, Calugaru E, et al. (2005). "12-year outcomes following permanent prostate brachytherapy in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer". The Journal of Urology. 173 (5): 1562–1566. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000154633.73092.8e. PMID 15821486. S2CID 14974301.

- ^ The American Brachytherapy Society: www.americanbrachytherapy.org

- ^ a b Frank SJ, Pisters LL, Davis J, et al. (2007). "An assessment of quality of life following radical prostatectomy, high dose external beam radiation therapy and brachytherapy iodine implantation as monotherapies for localized prostate cancer". The Journal of Urology. 177 (6): 2151–2156. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.134. PMID 17509305.

- ^ Lemoigne, Yves; Caner, Alessandra (2009-09-11). Radiotherapy and Brachytherapy. Springer. ISBN 9789048130955.

- ^ a b Salembier C, Lavagnini P, Nickers P, et al. (2007). "Tumour and target volumes in permanent prostate brachytherapy: a supplement to the ESTRO/EAU/EORTC recommendations on prostate brachytherapy". Radiotherapy and Oncology. 83 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2007.01.014. PMID 17321620.

- ^ a b c d e Ash D, Flynn A, Batterman J, et al. (2000). "ESTRO/EAU/EORTC recommendations on permanent seed implantation for localized prostate cancer". Radiotherapy and Oncology. 57 (3): 315–321. doi:10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00306-6. PMID 11104892.

- ^ a b National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment (2008). NICE clinical guidelines 58. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence

- ^ a b The Prostate Brachytherapy Advisory Group: www.prostatebrachytherapyinfo.net

- ^ Stewart, A.J.; Drinkwater, K.J.; Laing, R.W.; Nobes, J.P.; Locke, I. (June 2015). "The Royal College of Radiologists' Audit of Prostate Brachytherapy in the Year 2012". Clinical Oncology. 27 (6): 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2015.02.005. PMID 25727645.

- ^ Khaksar SJ, Laing RW, Henderson A, et al. (2006). "Biochemical (prostate-specific antigen) relapse-free survival and toxicity after 125I low-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy". BJU International. 98 (6): 1210–1215. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2006.06520.x. PMID 17034501.

- ^ Langley SE, Laing R. Prostate brachytherapy has come of age: a review of the technique and results. BJU International 2002;89:241–249

- ^ Crook J, Fleshner N, Roberts C, Pond G. Long-term urinary sequelae following 125Iodine prostate brachytherapy. The Journal of Urology 2008;179:141–146

- ^ Stone, N. N.; Stock, R. G. (2002-04-01). "Complications Following Permanent Prostate Brachytherapy". European Urology. 41 (4): 427–433. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00019-2. ISSN 0302-2838. PMID 12074815.

- ^ a b Buron, Catherine; Le Vu, Beatrice; Cosset, Jean-Marc; Pommier, Pascal; Peiffert, Didier; Delannes, Martine; Flam, Thierry; Guerif, Stephane; Salem, Naji; Chauveinc, Laurent; Livartowski, Alain (March 2007). "Brachytherapy versus prostatectomy in localized prostate cancer: Results of a French multicenter prospective medico-economic study". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 67 (3): 812–822. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.011. PMID 17293235.

- ^ a b c "Erectile Dysfunction After Prostate Cancer". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

External links

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2021

- Radiation therapy procedures

- Medical physics

- Male genital procedures

- Prostatic procedures

- Prostate cancer