Prolactinoma

| Prolactinoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Endocrinology, neurosurgery[1] |

| Symptoms | High prolactin: sexual dysfunction in males; decreased periods, infertility, milk production in females; decreased growth in children[1] Pressure effects: visual field defects, cranial nerve palsy, headaches[1] |

| Complications | Seizures, pituitary apoplexy[1] |

| Usual onset | Around 30 years[1] |

| Types | Micro, macro, giant[1] |

| Causes | Generally unclear[1] |

| Risk factors | Family history, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on lab tests and medical imaging after ruling out other causes[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pregnancy, certain medications, hypothyroidism[1] |

| Treatment | Periodically monitored, cabergoline, bromocriptine, hormone replacement therapy, surgery, radiation therapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Small (excellent), larger (mixed)[1] |

| Frequency | 2 per 10,000 people[1] |

A prolactinoma is a benign tumor of the pituitary gland that produces the hormone prolactin.[1] Symptoms result from high prolactin levels or pressure on surrounding tissues.[1] High prolactin can result in sexual dysfunction in males; decreased periods, infertility, and milk production in females; and decreased growth in children.[1] Pressure effects may include visual field defects, cranial nerve palsy, and headaches.[1] Complications may include seizures or pituitary apoplexy.[1]

The cause in most cases is unclear.[1][2] Risk factors include family history and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.[1] Diagnosis is based on lab tests and medical imaging after ruling out other possible causes.[1] They are classified into micro- (<10 mm diameter), macro- (10 to 40 mm diameter), and giant (>40 mm diameter).[1]

Small prolactinomas without symptoms may be simply periodically monitored.[1] Large or symptomatic cases may be treated with cabergoline and bromocriptine.[1] Hormone replacement therapy may also be used.[1] If this is not successful surgery or radiation therapy may be used.[1] Outcomes for small prolactinomas are generally excellent, while that of larger lesions is mixed.[1]

Prolactinomas affected about 2 per 10,000 people.[1] They are three times more common in women than men.[1] Onset is often around 30 years of age.[1] It is the most common type of functioning pituitary tumor.[3] Prolactinomas were first clearly described in the 1950s and 1960s.[4][5]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms due to a prolactinoma are broadly divided into those that are caused by increased prolactin levels or mass effect.

Those that are caused by increased prolactin levels are:[6]

- Amenorrhea (disappearance of ovulation periods)

- Galactorrhea (Milk production; infrequent in men)

- Loss of axillary and pubic hair

- Hypogonadism (Reduced function of the gonads.)

- Gynecomastia (an increase in male breast size)

- Erectile dysfunction (in males)

Those that are caused by mass effect are:

- Bitemporal hemianopsia (due to pressure on the optic chiasm)

- Vertigo

- Nausea, vomiting

Causes

The cause of pituitary tumors remains unknown. It has been shown that stress can significantly raise prolactin levels, which should make stress a diagnostic differential, though it usually is not considered such. Most pituitary tumors are sporadic — they are not genetically passed from parents to offspring.

The majority of moderately raised prolactin levels (up to 5000 mIU/L) are not due to microprolactinomas but other causes. The effects of some prescription drugs are the most common. Other causes are other pituitary tumours and normal pregnancy and breastfeeding. This is discussed more under hyperprolactinaemia.

The xenoestrogenic chemical Bisphenol-A has been shown to lead to hyperprolactinaemia and growth of prolactin-producing pituitary cells.[7] The increasing and prolonged exposure of Bisphenol-A from childhood on, may contribute to the growth of a Prolactinoma.

Diagnosis

A doctor will test for prolactin blood levels in women with unexplained milk secretion (galactorrhea) or irregular menses or infertility, and in men with impaired sexual function and, in rare cases, milk secretion. If prolactin is high, a doctor will test thyroid function and ask first about other conditions and medications known to raise prolactin secretion. The doctor will also request a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is the most sensitive test for detecting pituitary tumors and determining their size. MRI scans may be repeated periodically to assess tumor progression and the effects of therapy. CT scan also gives an image of the pituitary, but it is less sensitive than the MRI.

In addition to assessing the size of the pituitary tumor, doctors also look for damage to surrounding tissues, and perform tests to assess whether production of other pituitary hormones is normal. Depending on the size of the tumor, the doctor may request an eye exam with measurement of visual fields.

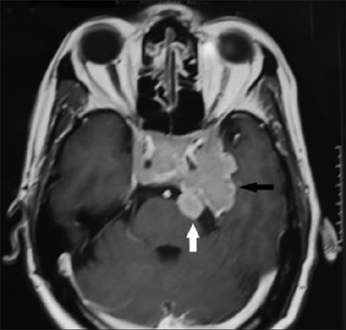

-

Invasive prolactinoma showing invasion into the left temporal lobe

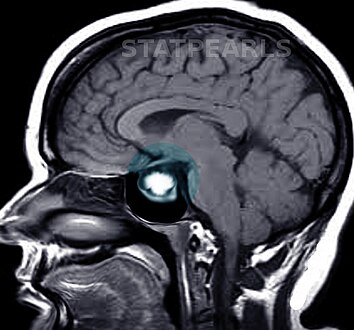

-

Prolactinoma on MRI

Treatments

The goal of treatment is to return prolactin secretion to normal, reduce tumor size, correct any visual abnormalities, and restore normal pituitary function. As mentioned above, the impact of stress should be ruled out before the diagnosis of prolactinoma is given. Exercise can significantly reduce stress and, thereby, prolactin levels. In the case of very large tumors, only partial reduction of the prolactin levels may be possible.

Medications

Dopamine is the chemical that normally inhibits prolactin secretion, so doctors may treat prolactinoma with bromocriptine, cabergoline or Quinagolide drugs that act like dopamine. This type of drug is called a dopamine agonist. These drugs shrink the tumor and return prolactin levels to normal in approximately 80% of patients. Both have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hyperprolactinemia. Bromocriptine is associated with side-effects such as nausea and dizziness and hypotension in patients with already low blood pressure readings. To avoid these side-effects, it is important for bromocriptine treatment to start slowly.

Bromocriptine treatment should not be interrupted without consulting a qualified endocrinologist. Prolactin levels often rise again in most people when the drug is discontinued. In some, however, prolactin levels remain normal, so the doctor may suggest reducing or discontinuing treatment every two years on a trial basis. Recent studies have shown increased success in remission of prolactin levels after discontinuation, in patients having been treated for at least 2 years prior to cessation of bromocriptine treatment.[8]

Cabergoline is also associated with side-effects such as nausea and dizziness, but these may be less common and less severe than with bromocriptine. However, people with low blood pressure should use caution when starting cabergoline treatment, as the long half-life of the drug (4–7 days) may inadvertently affect their ability to keep their blood pressure within normal limits, creating intense discomfort, dizziness, and even fainting upon standing and walking until the single first dose clears from their system. As with bromocriptine therapy, side-effects may be avoided or minimized if treatment is started slowly. If a patient's prolactin level remains normal for 6 months, a doctor may consider stopping treatment. Cabergoline should not be interrupted without consulting a qualified endocrinologist.

Surgery

Surgery should be considered if medical therapy cannot be tolerated or if it fails to reduce prolactin levels, restore normal reproduction and pituitary function, and reduce tumor size. If medical therapy is only partially successful, this therapy should continue, possibly combined with surgery or radiation treatment.

The results of surgery depend a great deal on tumor size and prolactin level. The higher the prolactin level the lower the chance of normalizing serum prolactin. In the best medical centers, surgery corrects prolactin levels in 80% of patients with a serum prolactin less than 250 ng/ml. Even in patients with large tumors that cannot be completely removed, drug therapy may be able to return serum prolactin to the normal range after surgery. Depending on the size of the tumor and how much of it is removed, studies show that 20 to 50% will recur, usually within five years.

Prognosis

People with microprolactinoma generally have an excellent prognosis. In 95% of cases the tumor will not show any signs of growth after a 4 to 6-year period.

Macroprolactinomas often require more aggressive treatment otherwise they may continue to grow. There is no way to reliably predict the rate of growth, as it is different for every individual. Regular monitoring by a specialist to detect any major changes in the tumor is recommended.

Osteoporosis

Hyperprolactinemia can cause reduced estrogen production in women and reduced testosterone production in men. Although estrogen/testosterone production may be restored after treatment for hyperprolactinemia, even a year or two without estrogen/testosterone can compromise bone strength, and patients should protect themselves from osteoporosis by increasing exercise and calcium intake through diet or supplementation, and by avoiding smoking. Patients may want to have bone density measurements to assess the effect of estrogen/testosterone deficiency on bone density. They may also want to discuss testosterone/estrogen replacement therapy with their physician.

Fertility

If a woman has one or more small prolactinoma, there is no reason that she cannot conceive and have a normal pregnancy after successful medical therapy. The pituitary enlarges and prolactin production increases during normal pregnancy in women without pituitary disorders. Women with prolactin-secreting tumors may experience further pituitary enlargement and must be closely monitored during pregnancy. However, damage to the pituitary or eye nerves occurs in less than one percent of pregnant women with prolactinoma. In women with large tumors, the risk of damage to the pituitary or eye nerves is greater, and some doctors consider it as high as 25%. If a woman has completed a successful pregnancy, the chances of her completing further successful pregnancies are extremely high.

A woman with a prolactinoma should discuss her plans to conceive with her physician, so she can be carefully evaluated prior to becoming pregnant. This evaluation will include a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to assess the size of the tumor and an eye examination with measurement of visual fields. As soon as a patient is pregnant, her doctor will usually advise that she stop taking bromocriptine or cabergoline, the common treatments for prolactinoma. Most endocrinologists see patients every two months throughout the pregnancy. The patient should consult her endocrinologist promptly if she develops symptoms — in particular, headaches, visual changes, nausea, vomiting, excessive thirst or urination, or extreme lethargy. Bromocriptine or cabergoline treatment may be renewed and additional treatment may be required if the person develops symptoms from growth of the tumor during pregnancy.

At one time, oral contraceptives were thought to contribute to the development of prolactinomas. However, this is no longer thought to be true. Patients with prolactinoma treated with bromocriptine or cabergoline may also take oral contraceptives. Likewise, post-menopausal estrogen replacement is safe in patients with prolactinoma treated with medical therapy or surgery.

Epidemiology

Autopsy studies indicate that 6-25% of the U. S. population have small pituitary tumors.[9] Forty percent of these pituitary tumors produce prolactin, but most are not considered clinically significant. Clinically significant pituitary tumors affect the health of approximately 14 out of 100,000 people. In non-selective surgical series, this tumor accounts for approximately 25-30% of all pituitary adenomas.[10] Some growth hormone (GH)–producing tumors also co-secrete prolactin. Microprolactinomas are much more common than macroprolactinomas.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 Yatavelli, RKR; Bhusal, K (January 2020). "Prolactinoma". PMID 29083585.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Prolactinoma | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ Glezer A, Bronstein MD (2015). "Prolactinomas". Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 44 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2014.11.003. PMID 25732643.

- ↑ Kronenberg, Henry (2007). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-4377-2181-2. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- ↑ Welbourn, Richard Burkewood; Friesen, Stanley R.; Johnston, Ivan D. A.; Sellwood, Ronald A. (1990). The History of Endocrine Surgery. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-275-92586-4. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- ↑ "Prolactinoma - PubMed Health". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-01-18. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- ↑ Goloubkova T, Ribeiro MF, Rodrigues LP, Cecconello AL, Spritzer PM (April 2000). "Effects of xenoestrogen bisphenol A on uterine and pituitary weight, serum prolactin levels and immunoreactive prolactin cells in ovariectomized Wistar rats". Arch. Toxicol. 74 (2): 92–8. doi:10.1007/s002040050658. PMID 10839476.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Bronstein MD (March 2006). "Potential for long-term remission of microprolactinoma after withdrawal of dopamine-agonist therapy". Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2 (3): 130–1. doi:10.1038/ncpendmet0135. PMID 16932269.

- ↑ McDowell BD, Wallace RB, Carnahan RM, Chrischilles EA, Lynch CF, Schlechte JA (March 2011). "Demographic differences in incidence for pituitary adenoma". Pituitary. 14 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1007/s11102-010-0253-4. PMC 3652258. PMID 20809113.

- ↑ Gandhi, Chirag D.; Post, Kalmon D. (2003-01-01). "PrL-Secreting Pituitary Adenomas". Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2016-12-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- Adapted from Prolactinoma. U. S. National Institutes of Health Publication No. 02-3924 June 2002. Public Domain Source

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |