Progressive massive fibrosis

| Progressive massive fibrosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Complicated pneumoconiosis | |

| |

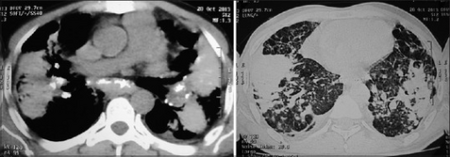

| Coalescence of nodules, lung parenchyma became fibrotic with appearance of bilateral conglomerated mass lesion, this confluent and consolidated shadow is indicative of progressive massive fibrosis | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Frequency | Lua error in Module:PrevalenceData at line 5: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

Progressive massive fibrosis (or Complicated pneumoconiosis[1]), characterized by the development of large conglomerate masses of dense fibrosis (usually in the upper lung zones), can complicate silicosis[2] and coal worker's pneumoconiosis.[3] Conglomerate masses may also occur in other pneumoconioses, such as talcosis,[4] berylliosis (CBD),[4] kaolin pneumoconiosis,[5] and pneumoconiosis from carbon compounds,[5] such as carbon black, graphite, and oil shale. Conglomerate masses can also develop in sarcoidosis,[6] but usually near the hilae and with surrounding paracicatricial emphysema.

The disease arises firstly through the deposition of silica or coal dust (or other dust) within the lung, and then through the body's immunological reactions to the dust.

Signs and symptoms

According to the International Labour Office (ILO), PMF requires the presence of large opacity exceeding 1 cm (by x-ray). By pathology standards, the lesion in histologic section must exceed 2 cm to meet the definition of PMF.[7] In PMF, lesions most commonly occupy the upper lung zone, and are usually bilateral. The development of PMF is usually associated with a restrictive ventilatory defect on pulmonary function testing. PMF can be mistaken for bronchogenic carcinoma and vice versa. PMF lesions tend to grow very slowly, so any rapid changes in size, or development of cavitation, should prompt a search for either alternative cause or secondary disease.[citation needed]

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of PMF is complicated, but involves two main routes – an immunological route, and a mechanical route.[citation needed]

Immunologically, disease is caused primarily through the activity of lung macrophages, which phagocytose dust particles after their deposition. These macrophages seek to eliminate the dust particle through either the mucociliary mechanism, or through lymphatic vessels which drain the lungs. Macrophages also produce an inflammatory mediator known as interleukin-1 (IL-1), which is part of the immune systems first line defenses against infecting particles. IL-1 is responsible for 'activation' of local vasculature, causing endothelial cells to express certain cell adhesion molecules, which help the cells of the body's immune system to migrate into tissues. Macrophages exposed to dust have been shown to have markedly decreased chemotaxis. Production of inflammatory mediators – and the tissue damage that ensues as an effect of this, as well as reduced motility of cells, is fundamental to the pathogenesis of pneumoconiosis and the accompanying inflammation, fibrosis, and emphysema.[citation needed]

There are also some mechanical factors involved in the pathogenesis of Complex Pneumoconiosis that should be considered. The most notable indications are the fact that the disease tends to develop in the upper lobe of the lung – especially on the right, and its common occurrence in taller individuals.

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of Progressive massive fibrosis we find that per a recent review the following is used in the evaluation:[8]

- Chest x-rays

- Chest CT

- Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- Magnetic resonance imaging

Treatment

Progressive massive fibrosis has no cure, it is irreversible[9]

Incidence

Progressive massive fibrosis increased during the period 1970–2016 among coal miners in central Appalachia who filed for black lung benefits.[10]

References

- ↑ "Progressive massive fibrosis (Concept Id: C0340170) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ↑ Ziskind M, Jones RN and Weill H. Silicosis: State of the Art. Am Rev Resp Dis, 1976;113:643–665.

- ↑ Hurley JF, Alexander WP, Hazledine DJ, Jacobsen M, Maclaren WM (October 1987). "Exposure to respirable coalmine dust and incidence of progressive massive fibrosis". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 44 (10): 661–72. doi:10.1136/oem.44.10.661. PMC 1007898. PMID 3676119.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chong S et al. Pneumoconiosis: Comparison of Imaging and Pathologic Findings. RadioGraphics, 2006;26:59-77.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Glazer CS and Newman LS. Occupational Interstitial Lung Disease. Clinics Chest Med, 2004;25:467–478.

- ↑ Pipavath S and Godwin JD. Imaging of Interstitial Lung Disease. Clinics Chest Med, 2004;25:455–465.

- ↑ Craighead JE et al. Diseases Associated with Exposure to Silica and Nonfibrous Silicate Minerals. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 1988;112:673–720.

- ↑ Weissman, David N. (December 2022). "Progressive massive fibrosis: An overview of the recent literature". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 240: 108232. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108232. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ↑ Hall, Noemi B.; Blackley, David J.; Halldin, Cara N.; Laney, A. Scott (September 2019). "Current Review of Pneumoconiosis Among US Coal Miners". Current Environmental Health Reports. 6 (3): 137–147. doi:10.1007/s40572-019-00237-5. ISSN 2196-5412. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ↑ Salynn Boyles (August 20, 2018). "Black Lung Disease Sees Significant Resurgence Central Appalachia epicenter of progressive massive fibrosis cases". Medpage Today. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

Primary Source: Annals of the American Thoracic Society Source Reference: Almberg KS, et al "Progressive massive fibrosis resurgence identified in U.S. coal miners filing for black lung benefits, 1970–2016" Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; DOI: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-261OC

- Occupational Lung Diseases, 3rd Edition, Morgan and https://web.archive.org/web/20060223051633/http://pim.medicine.dal.ca/il1.htm