Naegleriasis

| Naegleriasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), amoebic encephalitis, naegleria infection, amoebic meningitis | |

| |

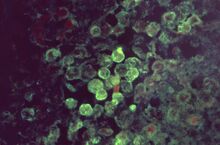

| Histopathology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. Direct fluorescent antibody stain. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Initial: Headache, fever, vomiting.[1] Later: Stiff neck, confusion, hallucinations, seizures[1] |

| Usual onset | 1 to 12 days after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Water contaminated by Naegleria fowleri up the nose[2] |

| Risk factors | Young males[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding evidence of the organism in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or brain tissue[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other causes of meningitis[5] |

| Prevention | Not putting the head underwater, avoid stirring up sediment, wearing a nose clip, chlorination[3] |

| Treatment | Amphotericin B, azithromycin, fluconazole, rifampin, miltefosine, dexamethasone, therapeutic hypothermia[6] |

| Frequency | Rare[1] |

| Deaths | 97.5% risk of death[1] |

Naegleriasis, also known as primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), is an infection of the brain by Naegleria fowleri.[3] Initial symptoms generally include headache, fever, nausea, and vomiting.[1] This is than followed by stiff neck, confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.[1] Onset is generally 1 to 12 days after exposure; with death usually occurring within 18 days.[1]

N. fowleri is typically found in warm bodies of fresh water, such as lakes, rivers, and hot springs; it also occurs in soil.[7] It grows best at temperatures of up to 46°C (115°F).[7] Infection may occur if contaminated water goes up the nose, such as during swimming or nasal irrigation.[2][7] It does not survive in seawater, does not spread between people, and does not occur following drinking contaminated water.[3][7] Diagnosis is confirmed by finding evidence of the organism in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or brain tissue.[4] It is a type of amoebic encephalitis.[8]

Water can be disinfected with chlorine.[7] Efforts to prevent infection include not putting the head underwater, avoiding stirring up sediment, and wearing a nose clip.[3] Treatment is typically with a combination of amphotericin B, azithromycin, fluconazole, rifampin, miltefosine, and dexamethasone.[6] Therapeutic hypothermia has also been used.[6]

Naegleriasis is rare, with 440 cases reported globally since 1962.[9] Most reports are from the United States, Australia, and France; with the belief that most cases in the developing world remain diagnosed.[10][11] There have been 157 cases documented between 1962 and 2022 in the United States (0 to 8 cases per year).[1][12] Of these cases 4 people (2.5%) survived.[1] Most cases occur in young males and occur during summer months.[3] Areas were the disease occurs appear to be expanding due to climate change.[5] The disease was first described in 1965 in Australia while the organism involved was described in 1899.[7][11]

Signs and symptoms

Onset of symptoms begins 1 to 12 days following exposure (with an average of five).[13] Initial symptoms include changes in taste and smell, headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, back pain, and a stiff neck.[14] Following this confusion, hallucinations, lack of attention, ataxia, cramp and seizures often occur. After the start of symptoms, the disease progresses over three to seven days, with death usually occurring anywhere from seven to fourteen days later.[15] In 2013, a man in Taiwan died 25 days after being infected by Naegleria fowleri.[16]

It most often affects healthy children or young adults who have recently been exposed to bodies of fresh water.[17] Some people have presented with a edematous brain lesions, immune suppression, and fever.[18]

Cause

N. fowleri invades the central nervous system via the nose, specifically through the olfactory mucosa of the nasal tissues. This usually occurs as the result of the introduction of water that has been contaminated with N. fowleri into the nose during activities such as swimming, bathing or nasal irrigation.[19]

The amoeba follows the olfactory nerve fibers through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone into the skull. There, it migrates to the olfactory bulbs and subsequently other regions of the brain, where it feeds on the nerve tissue. The organism then begins to consume cells of the brain, piecemeal through trogocytosis,[20] by means of an amoebostome, a unique actin-rich sucking apparatus extended from its cell surface.[21] It then becomes pathogenic, causing primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM or PAME).[citation needed]

Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis presents symptoms similar to those of bacterial and viral meningitis. Upon abrupt disease onset, a plethora of problems arise. Endogenous cytokines, which release in response to pathogens, affect the hypothalamus' thermoregulatory neurons and cause a rise in body temperature.[22] Additionally, cytokines may act on the vascular organ of the lamina terminalis, leading to the synthesis of prostaglandin (PG) E2 which acts on the hypothalamus, resulting in an increase in body temperature.[23] Also, the release of cytokines and exogenous exotoxins coupled with an increase in intracranial pressure stimulate nociceptors in the meninges[22] creating pain sensations.

The release of cytotoxic molecules in the central nervous system results in extensive tissue damage and necrosis, such as damage to the olfactory nerve through lysis of nerve cells and demyelination.[24] Specifically, the olfactory nerve and bulbs become necrotic and hemorrhagic.[25] Spinal flexion leads to nuchal rigidity, or stiff neck, due to the stretching of the inflamed meninges.[22] The increase in intracranial pressure stimulates the area postrema to create nausea sensations which may lead to brain herniation and damage to the reticular formation.[22] Ultimately, the increase in cerebrospinal fluid from inflammation of the meninges increases intracranial pressure and leads to the destruction of the central nervous system. Although the exact pathophysiology behind the seizures caused by PAM is unknown, scientists speculate that the seizures arise from altered meningeal permeability[22] caused by increased intracranial pressure.

Pathogenesis

Naegleria fowleri propagates in warm, stagnant bodies of fresh water (typically during the summer months), and enters the central nervous system after insufflation of infected water by attaching itself to the olfactory nerve.[17] It then migrates through the cribriform plate and into the olfactory bulbs of the forebrain,[27] where it multiplies itself greatly by feeding on nerve tissue.

Diagnosis

N. fowleri can be grown in several kinds of liquid axenic media or on non-nutrient agar plates coated with bacteria. Escherichia coli can be used to overlay the non-nutrient agar plate and a drop of cerebrospinal fluid sediment is added to it. Plates are then incubated at 37 °C and checked daily for clearing of the agar in thin tracks, which indicate the trophozoites have fed on the bacteria.[28]

Detection in water is performed by centrifuging a water sample with E. coli added, then applying the pellet to a non-nutrient agar plate. After several days, the plate is microscopically inspected and Naegleria cysts are identified by their morphology. Final confirmation of the species' identity can be performed by various molecular or biochemical methods.[29]

Confirmation of Naegleria presence can be done by a so-called flagellation test, where the organism is exposed to a hypotonic environment (distilled water). Naegleria, in contrast to other amoebae, differentiates within two hours into the flagellate state. Pathogenicity can be further confirmed by exposure to high temperature (42 °C): Naegleria fowleri is able to grow at this temperature, but the nonpathogenic Naegleria gruberi is not.[citation needed]

Prevention

Australia has had regulations since 2000 to test surface water that is used for swimming.[9] Wearing of nose clips to prevent entry of contaminated water may be effective protection.[30]

The Taiwan's Centers for Disease Control recommended people prevent fresh water from entering the nose and avoid putting their heads down into fresh water or stirring mud in the water with feet. When starting to have fever, headache, nausea, or vomiting subsequent to any kind of exposure to fresh water, even in the belief that no fresh water has traveled through the nostrils, people with such conditions should be carried to hospital quickly and make sure doctors are informed about the exposure to fresh water.[31]

Treatment

On the basis of the laboratory evidence and case reports, amphotericin B have been the traditional mainstay of PAM treatment since the first reported survivor in the United States in 1982.[32][33]

Treatment has often used combination therapy with multiple other antimicrobials in addition to amphotericin, such as fluconazole, miconazole, rifampicin and azithromycin. They have shown limited success only when administered early in the course of an infection.[34] Fluconazole is commonly used as it has been shown to have synergistic effects against naegleria when used with amphotericin.[32]

While the use of rifampicin has been common, including in all four North American cases of survival, its continued use has been questioned.[32] It only has variable activity in-vitro and it has strong effects on the therapeutic levels of other antimicrobials used by inducing cytochrome p450 pathways.[32]

In 2013, two successfully treated cases in the United States utilized the medication miltefosine.[35] As of 2015, there was no data on how well miltefosine is able to reach the central nervous system.[32] As of 2015 the U.S. CDC offered miltefosine to doctors for the treatment of free-living amoebas including naegleria.[35] In one of the cases, a 12-year-old female, was given miltefosine and targeted temperature management to manage cerebral edema that is secondary to the infection. She survived with no neurological damage. The targeted temperature management commingled with early diagnosis and the miltefosine medication has been attributed with her survival. On the other hand, the other survivor, an 8-year-old male, was diagnosed several days after symptoms appeared and was not treated with targeted temperature management; however, he was administered the miltefosine. He suffered what is likely permanent neurological damage.[35]

In 2016, a 16-year-old boy also survived PAM. He was treated with the same protocols of the 12-year-old girl in 2013. He recovered making a near complete neurological recovery; however, he has stated that learning has been more difficult for him since contracting the disease.[35][36]

In 2018, a 10-year-old girl was the first person to have PAM in Spain, and was successfully treated using intravenous and intrathecal amphotericin B.[37]

Prognosis

Since its first description in the 1960s, seven people worldwide have been reported to have survived PAM out of 450 cases diagnosed, implying a fatality rate of about 98.5%.[17] The survivors include four in the United States, one in Mexico and one in Spain. One of the US survivors had brain damage that is likely permanent, but there are two documented surviving cases in the United States who made a full recovery with no neurological damage; they were both treated with the same protocols.[35][32]

Epidemiology

The disease is rare with about 440 reported cases between 1962 and 2022.[9]

In the US, it most commonly occurs in southern states, with Texas and Florida having the highest rates. The most commonly affected age group is 5–14-year olds (those who play in water).[38] The number of cases of infection could increase due to climate change, which was posited as the reason for three cases in Minnesota in 2010, 2012, and 2015.[39][40]

As of 2013, the numbers of reported cases were expected to increase simply because of better-informed diagnoses being made both in ongoing cases and in autopsy findings.[41]

A single case has been reported in Japan as of 2018; occurring in 1996.[8] As of 2023 it has not been found in Canada.[42]

It is believed that younger age groups are at a higher risk because adolescents have a more underdeveloped and porous cribriform plate, through which the amoeba travels to reach the brain.[32]

History

In 1899, Franz Schardinger first discovered and documented an amoeba he called Amoeba gruberi that could transform into a flagellate.[43] The genus Naegleria was established by Alexis Alexeieff in 1912, who grouped the flagellate amoeba. He coined the term Naegleria after Kurt Nägler, who researched amoebae.[44] It was not until 1965 that doctors Malcolm Fowler and Rodney F. Carter in Adelaide, Australia, reported the first four human cases of amoebic meningoencephalitis. These cases involved four Australian children, one in 1961 and the rest in 1965, all of whom had succumbed to the illness.[45][46][47] Their work on amebo-flagellates has provided an example of how a protozoan can effectively live both freely in the environment, and in a human host.[48]

In 1966, Fowler termed the infection resulting from N. fowleri primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) to distinguish this central nervous system (CNS) invasion from other secondary invasions made by other amoebae such as Entamoeba histolytica.[48] A retrospective study determined the first documented case of PAM possibly occurred in Britain in 1909.[46] In 1966, four cases were reported in the US. By 1968 the causative organism, previously thought to be a species of Acanthamoeba or Hartmannella, was identified as Naegleria. This same year, occurrence of sixteen cases over a period of three years (1962–1965) was reported in Ústí nad Labem, Czechoslovakia.[49] In 1970, Carter named the species of amoeba N. fowleri, after Malcolm Fowler.[50][51]

Society and culture

Naegleria fowleri is also known as the "brain-eating amoeba". The term has also been applied to Balamuthia mandrillaris, causing some confusion between the two; Balamuthia mandrillaris is unrelated to Naegleria fowleri, and causes a different disease called granulomatous amoebic encephalitis. Unlike naegleriasis, which is usually seen in people with normal immune function, granulomatous amoebic encephalitis is usually seen in people with poor immune function, such as those with HIV/AIDS or leukemia.[52]

Naegleriasis was the topic of episodes 20 and 21 in Season 2 of the medical mystery drama House, M.D.[53][54]

Other animals

Other animals may also be infected, such as cattle.[10]

Research

The U.S. National Institutes of Health budgeted $800,000 for research on the disease in 2016.[55] Phenothiazines have been tested in vitro and in animal models.[56] Improving case detection through increased awareness, reporting, and information about cases might enable earlier detection of infections, provide insight into the human or environmental determinants of infection, and allow improved assessment of treatment effectiveness.[17] Corifungin is another possible treatment.[5]

See also

- Balamuthia mandrillaris – unrelated pathogenic organism that shares the same common name as N. fowleri

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 "Illness and Symptoms | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 3 May 2023. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Naegleria fowleri — Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM) — Amebic Encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 3 May 2023. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Facts about Naegleria fowleri and Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis" (PDF). CDC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Diagnosis | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Cooper, AM; Aouthmany, S; Shah, K; Rega, PP (June 2019). "Killer amoebas: Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in a changing climate". JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 32 (6): 30–35. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000558238.99250.4a. PMID 31136398.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Treatment | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 3 May 2023. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 "Pathogen and Environment | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hara, T; Yagita, K; Sugita, Y (August 2019). "Pathogenic free-living amoebic encephalitis in Japan". Neuropathology : official journal of the Japanese Society of Neuropathology. 39 (4): 251–258. doi:10.1111/neup.12582. PMID 31243796.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Amoebic meningoencephalitis". The Encephalitis Society. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Canada, Public Health Agency of (8 September 2011). "Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Naegleria fowleri". www.canada.ca. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Siddiqui, R; Khan, NA (August 2014). "Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri: an old enemy presenting new challenges". PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 8 (8): e3017. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003017. PMID 25121759.

- ↑ "Prevention & Control | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 3 May 2023. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ "Illness & Symptoms | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". cdc.gov. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ↑ Talaro, Kathleen (2015). Foundations in microbiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 695. ISBN 978-0-07-352260-9.

- ↑ "CDC—01 This Page Has Moved: CDC Parasites Naegleria". Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Su MY, Lee MS, et al. (Apr 2013). "A fatal case of Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis in Taiwan". Korean J Parasitol. 51 (2): 203–6. doi:10.3347/kjp.2013.51.2.203. PMC 3662064. PMID 23710088.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2008). "Primary amebic meningoencephalitis – Arizona, Florida, and Texas, 2007". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (21): 573–7. PMID 18509301. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ↑ Mayer, Peter (2011). "Amebic encephalitis". Surgical Neurology International. 50 (2): 50. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.80115. PMC 3114370. PMID 21697972.

- ↑ "Safe Ritual Nasal Rinsing" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ↑ Gilmartin, Allissia A.; Petri, Jr, William A. (2018). "Exploring the mechanism of amebic trogocytosis: the role of amebic lysosomes". Microbial Cell. 5 (1): 1–3. doi:10.15698/mic2018.01.606. ISSN 2311-2638. PMC 5772035. PMID 29354646.

- ↑ Marciano-Cabral, F; John, DT (1983). "Cytopathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri for rat neuroblastoma cell cultures: scanning electron microscopy study". Infection and Immunity. 40 (3): 1214–7. doi:10.1128/IAI.40.3.1214-1217.1983. PMC 348179. PMID 6852919.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Montgomery, Katherine. "Meningitis". McMaster Pathophysiology Review. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ↑ Walter, Edward James; Hanna-Jumma, Sameer; Carraretto, Mike; Forni, Lui (14 July 2016). "The pathophysiological basis and consequences of fever". Critical Care. 20 (1): 200. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1375-5. ISSN 1364-8535. PMC 4944485. PMID 27411542.

- ↑ Pugh, J. Jeffrey; Levy, Rebecca A. (21 September 2016). "Naegleria fowleri: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology of Brain Inflammation, and Antimicrobial Treatments". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 7 (9): 1178–1179. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00232. PMID 27525348..

- ↑ Fero, Kelly. "Naegleria fowleri". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ↑ Gallois, R.W. (2006). "The geology of the hot springs at Bath Spa, Somerset". Geoscience in South-west England. 11 (3): 170. Archived from the original on 2021-12-06. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- ↑ Cervantes-Sandoval I, Serrano-Luna Jde J, García-Latorre E, Tsutsumi V, Shibayama M (September 2008). "Characterization of brain inflammation during primary amoebic meningoencephalitis". Parasitol. Int. 57 (3): 307–13. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2008.01.006. PMID 18374627.

- ↑ Donald C. Lehman; Mahon, Connie; Manuselis, George (2006). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2581-8.[page needed]

- ↑ Pougnard, C.; Catala, P.; Drocourt, J.-L.; Legastelois, S.; Pernin, P.; Pringuez, E.; Lebaron, P. (2002). "Rapid Detection and Enumeration of Naegleria fowleri in Surface Waters by Solid-Phase Cytometry". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 68 (6): 3102–7. Bibcode:2002ApEnM..68.3102P. doi:10.1128/AEM.68.6.3102-3107.2002. PMC 123984. PMID 12039772.

- ↑ "6 die from brain-eating amoeba in lakes", Chris Kahn/Associated Press, 9/28/07

- ↑ "福氏內格里阿米巴腦膜腦炎感染病例罕見,但致死率高,籲請泡溫泉及從事水上活動之民眾小心防範". 衛生福利部疾病管制署 (in 中文). 2013-10-26. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 2017-10-14.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Grace, Eddie; Asbill, Scott; Virga, Kris (2015-11-01). "Naegleria fowleri: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 59 (11): 6677–6681. doi:10.1128/AAC.01293-15. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 4604384. PMID 26259797.

- ↑ The American Heritage Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2004. ISBN 9780618428991.

- ↑ Bauman, Robert W. (2009). "Microbial Diseases of the Nervous System and Eyes". Microbiology, With Diseases by Body System (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Education. p. 617.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 "Naegleria fowleri – Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM) – Amebic Encephalitis". 23 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Diaz, Johnny. "Teen who survived brain-eating amoeba says sickness gave him more positive outlook". sun-sentinel.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ Güell, Oriol (12 October 2018). "Una niña de Toledo sobrevive al primer caso en España de la ameba comecerebros". El País. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ↑ "Number of Case-Reports of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Caused by Naegleria Fowleri (N=133) by State of Exposure*— United States, 1962–2014". CDC.gov, CDC, www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/pdf/naegleria-state-map-2014.pdf.

- ↑ Kemble SK, Lynfield R, et al. (Mar 2012). "Fatal Naegleria fowleri infection acquired in Minnesota: possible expanded range of a deadly thermophilic organism". Clin Infect Dis. 54 (6): 805–9. doi:10.1093/cid/cir961. PMID 22238170.

- ↑ Lorna Benson (2015-07-09). "Has deadly water amoeba found a home in Minnesota?". Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ Kanwal Farooqi M, Ali S, Ahmed SS (May 2013). "The paradox of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis—a rare disease, but commonly misdiagnosed". J Pak Med Assoc. 63 (5): 667. PMID 23758009.

- ↑ Dey, Rafik; Dlusskaya, Elena; Oloroso, Mariem; Ashbolt, Nicholas J. (1 March 2023). "First evidence of free-living Naegleria species in recreational lakes of Alberta, Canada". Journal of Water and Health. 21 (3): 439–442. doi:10.2166/wh.2023.325.

- ↑ Jonckheere, Johan F. De (November 2014). "What do we know by now about the genus Naegleria?". Experimental Parasitology. 145 (Supplement): S2-9. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2014.07.011. PMID 25108159.

- ↑ Walochnik, Julia; Wylezich, Claudia; Michel, Rolf (September 2010). "The genus Sappinia: History, phylogeny and medical relevance". Experimental Parasitology. 126 (1): 5, 7–8. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2009.11.017. PMID 20004196.

- ↑ Fowler, M.; Carter, R. F. (September 1965). "Acute pyogenic meningitis probably due to Acanthamoeba sp.: a preliminary report". British Medical Journal. 2 (5464): 740–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5464.734-a. PMC 1846173. PMID 5825411.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Symmers, W. S. C. (November 1969). "Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in Britain". British Medical Journal. 4 (5681): 449–54. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5681.449. PMC 1630535. PMID 5354833.

- ↑ Martinez, Augusto Julio; Visvesvara, Govinda S. (1997). "Free-living, Amphizoic and Opportunistic Amebas". Brain Pathology. 7 (1): 584. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1997.tb01076.x. PMC 8098488. PMID 9034567.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Butt, Cecil G. (1966). "Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 274 (26): 1473–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM196606302742605. PMID 5939846.

- ↑ Červa, L.; Novák, K. (April 1968). "Ameobic meningoencephalitis: sixteen fatalities". Science. 160 (3823): 92. Bibcode:1968Sci...160...92C. doi:10.1126/science.160.3823.92. PMID 5642317. S2CID 84686553.

- ↑ Gutierrez, Yezid (15 January 2000). "Chapter 6: Free Living Amebae". Diagnostic Pathology of Parasitic Infections with Clinical Correlations (2 ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0-19-512143-8.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ↑ De Jonckheere, Johan F. (August 2011). "Origin and evolution of the worldwide distributed pathogenic amoeboflagellate Naegleria fowleri". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 11 (7): 1520–1528. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2011.07.023. PMID 21843657.

- ↑ Shadrach, WS; Rydzewski, K; Laube, U; Holland, G; Ozel, M; Kiderlen, AF; Flieger, A (May 2005). "Balamuthia mandrillaris, free-living ameba and opportunistic agent of encephalitis, is a potential host for Legionella pneumophila bacteria". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 71 (5): 2244–9. Bibcode:2005ApEnM..71.2244S. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.5.2244-2249.2005. PMC 1087515. PMID 15870307.

- ↑ "IMDB, Euphoria: Part 1". IMDb. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ "IMDB, Euphoria: Part 2". IMDb. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ Wessel, Lindzi (22 July 2016). "Scientists hunt for drug to kill deadly brain-eating amoeba". STAT News. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ↑ Kim, J.-H.; Jung, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.-J.; Song, K.-J.; Kwon, D.; Kim, K.; Park, S.; Im, K.-I.; Shin, H.-J. (2008). "Effect of Therapeutic Chemical Agents In Vitro and on Experimental Meningoencephalitis Due to Naegleria fowleri". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 52 (11): 4010–6. doi:10.1128/AAC.00197-08. PMC 2573150. PMID 18765686.

External links

- Naegleria Infection Information Page Archived 11 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

| Classification |

|---|

- Pages with script errors

- Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from August 2011

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- CS1 中文-language sources (zh)

- Wikipedia articles incorporating the PD-notice template

- CS1 errors: external links

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2020

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Parasitic excavates

- Percolozoa

- Waterborne diseases

- Rare infectious diseases

- Neglected American diseases

- RTT