Petechiae

| Petechiae | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Petechia | |

| |

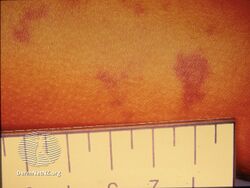

| Petechia and purpura on the low limb due to medication-induced vasculitis | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Red spots less than 2 mm[1] |

| Causes | Infections: Enterovirus, Dengue, meningococcal disease[2] Injury: Non accidental trauma, coughing, vomiting[2] Blood disorders Leukemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura[2] Other Henoch-Schonlein purpura, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, drug reactions, vitamin K deficiency[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Purpura, ecchymosis, hematoma[2][3] |

| Frequency | Common[2] |

Petechiae are small (less than 2 mm) red or purple spot in the skin or mucous membranes caused by minor bleeding from a broken capillary blood vessels.[1][3] They do not turn white when pushed on.[2] Some causes, such as coughing and vomiting, only produce petechiae above the nipple line.[2]

Causes include infections such as enterovirus, Dengue, or meningococcal disease; injury such as non accidental trauma, coughing, or vomiting; blood disorders such as leukemia and idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura; vasculitis such as Henoch-Schonlein purpura; connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome; drug reactions; and vitamin K deficiency.[2] The underlying mechanism involves bleeding into the skin, often as a result of low platelets, platelet dysfunction, blood clotting disorders, and loss of vascular integrity.[2]

Petechiae are one of the three types of bleeding into the skin, with the other two being purpura and ecchymosis (bruise).[4] Purpura are 2–10 millimetres in diameter while ecchymosis are defined as larger than 1 centimeter.[3][1] A hematoma in contrast is a deeper bruise.[3]

Treatment depends on the underlying cause.[2] This may vary from simply reassurance to intravenous antibiotics, or hospital admission.[2] Petechiae are common.[2] They represent the reason for about 2.5% of visits to pediatric emergency departments.[2] They were first described in 1855 by Auguste Ambroise Tardieu.[5] The word is derived from Latin for "a spot".[6]

Signs and symptoms

Small (less than 2 mm) red or purple spot in the skin or mucous membranes.[1] They do not turn white when pushed on.[2]

-

Meningococcal petechiae

-

Meningococcal petechiae

-

Petechiae due to thrombocytopenia

Causes

Injury

The most common cause of petechiae is through physical trauma such as a hard bout of coughing, holding breath, vomiting, or crying, which can result in facial petechiae, especially around the eyes. Such instances are harmless and usually disappear within a few days.

- Constriction, Asphyxiation – Petechiae, especially in the eyes, may also occur when excessive pressure is applied to tissue (e.g., when a tourniquet is applied to an extremity or with excessive coughing or vomiting).

- Sunburn, childbirth, weightlifting[7]

- Gua Sha, a Chinese treatment that scrapes the skin

- High-G training

- Hickey

- Asphyxiation

- Choking game

- Oral sex[8]

Non-infectious

- Vitamin C deficiency, scurvy[7]

- Vitamin K deficiency[7]

- Leukemia[7]

- Thrombocytopenia – Low platelet counts or diminished platelet function (e.g., as a side effect of medications, vaccines such as COVID-19_vaccine or during certain infections) can give rise to petechial spots[1]

- clotting factor deficiencies – (Von Willebrand disease)

- Hypocalcemia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Coeliac disease

- Aplastic anaemia

- Lupus

- Kwashiorkor or Marasmus – Childhood protein-energy malnutrition

- Erythroblastosis fetalis

- Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Kawasaki disease

- Schamberg disease

- Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Sjögren syndrome – Petechial spots could occur due to vasculitis, an inflammation of the blood vessels. In such a case immediate treatment is needed to prevent permanent damage. Some malignancies can also cause petechiae to appear.

Infectious

- Babesiosis

- Bolivian hemorrhagic fever

- Boutonneuse fever

- Chikungunya

- Cerebral malaria

- Congenital syphilis

- Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever

- Cytomegalovirus

- Dengue fever

- Dukes' disease

- Ebola

- Endocarditis

- Influenza A virus subtype H1N1

- Hantavirus

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Marburg virus

- Neisseria meningitidis

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

- Scarlet fever

- Typhus[9]

- Streptococcal pharyngitis – Petechiae on the soft palate are mainly associated with streptococcal pharyngitis,[10] and as such it is an uncommon but highly specific finding.[11]

Society and culture

Terminology

The term is almost always used in the plural (petechiae), since a single lesion is seldom noticed or significant.

Forensic science

Petechiae on the face and conjunctiva (eyes) are unrelated to asphyxiation or hypoxia.[12]

Despite this, petechiae are used by police investigators in determining whether strangulation has been part of an attack. The documentation of the presence of petechiae on a victim can help police investigators prove the case.[13] Petechiae resulting from strangulation can be relatively tiny and light in color to very bright and pronounced. Petechiae may be seen on the face, in the whites of the eyes or on the inside of the eyelids.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Kumar, Vinay (2017). Robbins Basic Pathology. Abbas, Abul K.; Aster, Jon C.; Perkins, James A. (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA. p. 101. ISBN 978-0323353175. OCLC 960844656.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 McGrath, A; Barrett, MJ (January 2021). "Petechiae". PMID 29493956.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Bleeding and bruising | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ↑ "Purpura". fpnotebook.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ↑ Orient, Jane M.; Sapira, Joseph D. (2010). Sapira's Art & Science of Bedside Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-60547-411-3. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ↑ Talley, Nicholas J.; O’Connor, Simon (2013). Clinical Examination: A Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-7295-8147-9. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Causes". Archived from the original on 2015-04-22. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- ↑ Schlesinger, SL; Borbotsina, J; O'Neill, L (September 1975). "Petechial hemorrhages of the soft palate secondary to fellatio". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 40 (3): 376–78. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(75)90422-3. PMID 1080847.

- ↑ Grayson MD, Charlotte (2006-09-26). "Typhus". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ Fact Sheet: Tonsillitis Archived 2014-04-06 at the Wayback Machine from American Academy of Otolaryngology. "Updated 1/11". Retrieved November 2011

- ↑ Brook I, Dohar JE (December 2006). "Management of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis in children". J Fam Pract. 55 (12): S1–11, quiz S12. PMID 17137534.

- ↑ Ely, Susan F.; Charles S. Hirsch (2000). "Asphyxial deaths and petechiae: a review" (PDF). Journal of Forensic Sciences. 45 (6): 1274–1277. doi:10.1520/JFS14878J. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-03-09. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ↑ "Investigating Domestic Violence Strangulation". BlueSheepdog.com. 2007-11-09. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

| Look up petechia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |