Hypospadias

| Hypospadias | |

|---|---|

| Other names: pronounce = /haɪpoʊˈspeɪdiəs/[1][2] | |

| |

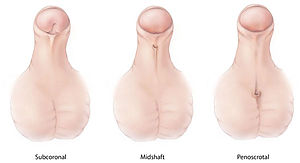

| Different types of hypospadias | |

| Specialty | Urology, medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Urethra opens near the head of the penis, along the shaft of the penis, or near the scrotum[3] |

| Complications | Decreased fertility[4] |

| Usual onset | Present at birth[3] |

| Types | Distal (subcoronal), middle (midshaft), posterior (penoscrotal)[3][4] |

| Causes | Generally unknown[3] |

| Risk factors | Family history, mother > 35, fertility treatments, certain hormones[3][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Examination[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Disorders of sex development[4] |

| Treatment | Surgery[3] |

| Frequency | 1 in 200 males[3] |

Hypospadias is a birth defect in which the urethra does not open at the tip of the penis.[3] Instead it opens near the head of the penis, along the shaft of the penis, or near the scrotum.[3] There may also be a greater amount of foreskin at the back than front of the penis.[4] Other problems may include a curved penis or undescended testicles.[3] Complications may include decreased fertility.[4]

The cause is generally unknown.[3] Risk factors include a family history, mothers greater than 35 years old when pregnant, fertility treatments, and certain hormones.[3][4] It may also occur as a part of a number of syndromes.[4] Diagnosis is generally by examination at birth.[3] It is divided into three types distal (subcoronal), middle (midshaft), and posterior (penoscrotal).[3][4]

Many cases of hypospadias are treated by surgery.[3] This is generally done when the child is 3 to 18 months old.[3] Those affected should not be circumcised.[3] It affects about 1 in 200 males at birth in the United States and Europe, though may be less common in other parts of the world.[3][4] It is the second-most common birth abnormality of the male reproductive system after undescended testicles.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Roughly 90% of cases are the less serious distal hypospadias, in which the urethral opening is on or near the head of the penis. The remainder have proximal hypospadias, in which the meatus is on the shaft of the penis or within the scrotum. In most cases, the foreskin is less developed and does not wrap completely around the penis, leaving the underside of the glans uncovered. Also, a downward bending of the penis may occur.[5] This is found in 10% of distal hypospadias[6] and 50% of proximal hypospadias.[7] The scrotum may be higher than usual on either side of the penis (called penoscrotal transposition).

-

Example of penis with hypospadias

-

Penis with hypospadias (1) and two fistulae (2)

Complications

There is noted to be an increase in erectile problems in people with hypospadias, particularly when associated with a chordee (down curving of the shaft). There is usually minimal interaction with ability to ejaculate in hypospadias providing the meatus remains distal. This can also be affected by the coexistence of posterior urethral valves. There is an increase in difficulties associated with ejaculation however including increased rate of pain on ejaculation and weak/dribbling ejaculation. The rates of these problems are the same regardless of whether or not the hypospadias is surgically corrected.[8]

Hypospadias can be a symptom or indication of an intersex condition, but the presence of hypospadias alone is not enough to classify a person as intersex. In most cases, hypospadias is not associated with any other condition.[9] The most common associated difference is an undescended testicle, which has been reported in around 3% of infants with distal hypospadias and 10% with proximal hypospadias.[10] The combination of hypospadias and an undescended testicle sometimes indicates a child has an intersex condition, so additional testing may be recommended to make sure the child does not have congenital adrenal hyperplasia with salt wasting or a similar condition where immediate medical intervention is needed.[11][12] Otherwise no blood tests or X-rays are routinely needed in newborns with hypospadias.[6]

Diagnosis

A penis with hypospadias usually has a characteristic appearance. Not only is the meatus (urinary opening) lower than usual, but the foreskin is also often only partially developed, lacking the usual amount that would cover the glans on the underside, causing the glans to have a hooded appearance. However, newborns with partial foreskin development do not necessarily have hypospadias, as some have a meatus in the usual place with a hooded foreskin, called “chordee without hypospadias”.

In other cases, the foreskin (prepuce) is typical and the hypospadias is concealed. This is called "megameatus with intact prepuce". The condition is discovered during newborn circumcision or later in childhood when the foreskin begins to retract. A newborn with typical-appearing foreskin and a straight penis who is discovered to have hypospadias after the start of circumcision can have circumcision completed without concern for jeopardizing hypospadias repair.[13][14] Hypospadias is almost never discovered after a circumcision.[citation needed]

Treatment

Where hypospadias is seen as a genital ambiguity in a child, the World Health Organization standard of care is to delay surgery until the child is old enough to participate in informed consent, unless emergency surgery is needed because the child lacks a urinary opening. Hypospadias is not a serious medical condition. A urinary opening that is not surrounded by glans tissue is more likely to “spray” the urine, which can cause a man to sit to urinate because he cannot reliably stand and hit the toilet. Chordee is a separate condition, but where it occurs, the downward curvature of the penis may be enough to make sexual penetration more difficult. For these reasons or others, people with hypospadias may choose to seek urethroplasty, a surgical extension of the urethra using a skin graft.

Surgery can extend the urinary channel to the end of the penis, straighten bending, and/or change the foreskin (by either circumcision or by altering its appearance to look more typical (“prepucioplasty”), depending on the desire of the patient. Urethroplasty failure rates vary enormously, from around 5% for the simplest repairs to damage in a normal urethra by an experienced surgeon, to 15-20% when a buccal graft from the inside of the mouth can be used to extend a urethra, to close to 50% when graft urethral tubes are constructed from other skin.[15]

When the hypospadias is extensive--third degree/penoscrotal--or has associated differences in sex development such as chordee or cryptorchidism, the best management can be a more complicated decision. The world standard (UN and WHO) forbids nonessential surgery to produce a "normal" appearance without the informed consent of the patient[16], and the American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends but does not require the same standard. The AAP Textbook of Pediatric Care states "Gender assignment in patients with genital ambiguity should be made only after careful investigation by a multidisciplinary team; increasingly, surgical decisions are delayed until the child is able to participate in the decision-making process." [17] A karyotype and endocrine evaluation should be performed to detect intersex conditions or hormone deficiencies that have major health risks (i.e. salt-wasting). If the penis is small, testosterone or human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) injections may be given with consent to enlarge it before surgery if this will increase the chance of a successful urethral repair.[6]

Surgical repair of severe hypospadias may require multiple procedures and mucosal grafting. Preputial skin is often used for grafting and circumcision should be avoided before repair. In patients with severe hypospadias, surgery often produces unsatisfactory results, such as scarring, curvature, or formation of urethral fistulas, diverticula, or strictures. A fistula is an unwanted opening through the skin along the course of the urethra, and can result in urinary leakage or an abnormal stream. A diverticulum is an "outpocketing" of the lining of the urethra which interferes with urinary flow and may result in posturination leakage. A stricture is a narrowing of the urethra severe enough to obstruct flow. Reduced complication rates even for third-degree repair (e.g., fistula rates below 5%) have been reported in recent years from centers with the most experience.[18] However, typical complications in urethroplasty for severe hypospadias can lead to long surgical cycles of failure and repair, and side effects may include loss of sexual or urinary function.[19] Research suggests failure rates are higher when urethroplasty corrects a born condition rather than disease or injury[20] so patients and families considering surgery for hypospadias should have realistic expectations about the risks and benefits.[21]

Age at surgery

The results of surgery are probably not influenced by the age at which repair is done.[22][23] Teens and adults typically spend one night in the hospital after surgery.

Preoperative hormones

Hormones potentially increase the size of the penis, and have been used in children with proximal hypospadias who have a smaller penis. Numerous articles report testosterone injections or topical creams increase the length and circumference of the penis. However, few studies discuss the impact of this treatment on the success of corrective surgery, with conflicting results.[23][24] Therefore, the role, if any, for preoperative hormone stimulation is not clear at this time.

Surgery

Hypospadias repair is done under general anesthesia, most often supplemented by a nerve block to the penis or a caudal block to reduce the general anesthesia needed, and to minimize discomfort after surgery.

Many techniques have been used during the past 100 years to extend the urinary channel to the desired location. Today, the most common operation, known as the tubularized incised plate or “TIP” repair, rolls the urethral plate from the low meatus to the end of the glans. TIP repair, also called the Snodgrass Repair (after the creator of the method, Dr. Warren Snodgrass), is the most widely-used procedure and surgical method for hypospadias repair worldwide. This procedure can be used for all distal hypospadias repairs, with complications afterwards expected in less than 10% of cases.[25][26]

Less consensus exists regarding proximal hypospadias repair.[27] TIP repair can be used when the penis is straight or has mild downward curvature, with success in 85%.[25] Alternatively, the urinary channel can be reconstructed using the foreskin, with reported success in from 55% to 75%.[28]

Most distal and many proximal hypospadias are corrected in a single operation. However, those with the most severe condition having a urinary opening in the scrotum and downward bending of the penis are often corrected in a two-stage operation. During the first operation the curvature is straightened. At the second, the urinary channel is completed. Any complications may require additional interventions for repair.

While most hypospadias repairs are done in childhood, occasionally, an adult desires surgery because of urinary spraying or unhappiness with the appearance. Other adults wanting surgery have long-term complications as a result of childhood surgeries. A direct comparison of surgical results in children versus adults found they had the same outcomes, and adults can undergo hypospadias repair or reoperations with good expectations for success.[23]

Outcomes

Most non-intersex children having hypospadias repair heal without complications. This is especially true for distal hypospadias operations, which are successful in over 90% of cases.

Problems that can arise include a small hole in the urinary channel below the meatus, called a fistula. The head of the penis, which is open at birth in children with hypospadias and is closed around the urinary channel at surgery, sometimes reopens, known as glans dehiscence. The new urinary opening can scar, resulting in meatal stenosis, or internal scarring can create a stricture, either of which cause partial blockage to urinating. If the new urinary channel balloons when urinating a child is diagnosed with a diverticulum.

Most complications are discovered within six months after surgery, although they occasionally are not found for many years. In general, when no problems are apparent after repair in childhood, new complications arising after puberty are uncommon. However, some problems that were not adequately repaired in childhood may become more pronounced when the penis grows at puberty, such as residual penile curvature or urine spraying due to rupture of the repair at the head of the penis.

Complications are usually corrected with another operation, most often delayed for at least six months after the last surgery to allow the tissues to heal sufficiently before attempting another repair. Results when circumcision or foreskin reconstruction are done are the same.[29][30] (Figure 4a, 4b)

Patients and surgeons had differing opinions as to outcomes of hypospadias repair, that is, patients might not be satisfied with a cosmetic result considered satisfactory by the surgeon, but patients with a cosmetic result considered not very satisfactory by the surgeon may themselves be satisfied. Overall, patients were less satisfied than surgeons.[8]

Epidemiology

Hypospadias is among the most common birth defects in the world and is said to be the second-most common birth defect in the male reproductive system, occurring once in every 250 males.[31]

Due to variations in the reporting requirements of different national databases, data from such registries cannot be used to accurately determine either incidence of hypospadias or geographical variations in its occurrences.[6]

References

- ↑ Entry "hypospadias" Archived 2020-12-12 at the Wayback Machine in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary Archived 2017-09-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ OED 2nd edition, 1989 as /hɪpəʊˈspeɪdɪəs/~/haɪpəʊˈspeɪdɪəs/

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 "Facts about Hypospadias | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 December 2019. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Donaire, AE; Mendez, MD (January 2020). "Hypospadias". PMID 29489236.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ King S, Beasley S (2012) [1st. Pub. 1986]. "Chapter 9.1:Surgical Conditions in Older Children". In South M (ed.). Practical Paediatrics, Seventh Edition. Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-0-702-04292-8.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Snodgrass, Warren (2012). "Chapter 130: Hypospadias". In Wein, Allan; Campbell, Meredith F; Walsh, Patrick C (eds.). Campbell-Walsh Urology, Tenth Edition. Elsevier. pp. 3503–3536. ISBN 978-1-4160-6911-9.

- ↑ Snodgrass W, Prieto J (October 2009). "Straightening ventral curvature while preserving the urethral plate in proximal hypospadias repair". The Journal of Urology. 182 (4 Suppl): 1720–5. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.084. PMID 19692004.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Mieusset R, Soulié M (2005). "Hypospadias: psychosocial, sexual, and reproductive consequences in adult life". Journal of Andrology. 26 (2): 163–8. doi:10.1002/j.1939-4640.2005.tb01078.x. PMID 15713818.

- ↑ Tidy, Colin (January 19, 2016). "Hypospadias". Patient. Patient Platform Ltd. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ↑ Wu, Hongfei; Wei, Zhang; M., Gu (2002). "Hypospadias and enlarged prostatic utricle". Chinese Journal of Urology. 12: 51–3. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-11.

- ↑ Kaefer M, Tobin MS, Hendren WH, Bauer SB, Peters CA, Atala A, et al. (April 1997). "Continent urinary diversion: the Children's Hospital experience". The Journal of Urology. 157 (4): 1394–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64998-X. PMID 9120962.

- ↑ Tarman GJ, Kaplan GW, Lerman SL, McAleer IM, Losasso BE (January 2002). "Lower genitourinary injury and pelvic fractures in pediatric patients". Urology. 59 (1): 123–6, discussion 126. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01526-6. PMID 11796295.

- ↑ Snodgrass WT, Khavari R (July 2006). "Prior circumcision does not complicate repair of hypospadias with an intact prepuce". The Journal of Urology. 176 (1): 296–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00564-7. PMID 16753427.

- ↑ Chalmers D, Wiedel CA, Siparsky GL, Campbell JB, Wilcox DT (May 2014). "Discovery of hypospadias during newborn circumcision should not preclude completion of the procedure". The Journal of Pediatrics. 164 (5): 1171–1174.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.013. PMID 24534572.

- ↑ "Urethroplasty". Department of Urology. 2016-06-06. Archived from the original on 2019-06-11. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ↑ "United Nations Fact Sheet-Intersex" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-02.

- ↑ "Disorders of Sex Development | American Academy of Pediatrics Textbook of Pediatric Care, 2nd Edition | Pediatric Care Online | AAP Point-of-Care-Solutions". pediatriccare.solutions.aap.org. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ↑ "Re operation with Dr Nicol Bush & Dr Warren Snodgrass". PARC Urology Hypospadias Center. 2016-07-15. Archived from the original on 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ↑ "Urethroplasty - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Archived from the original on 2019-09-22. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ↑ Suh JG, Choi WS, Paick JS, Kim SW (July 2013). "Surgical Outcome of Excision and End-to-End Anastomosis for Bulbar Urethral Stricture". Korean Journal of Urology. 54 (7): 442–7. doi:10.4111/kju.2013.54.7.442. PMC 3715707. PMID 23878686.

- ↑ "What are some of the risks of penile surgery?". ISSM. 2012-02-21. Archived from the original on 2019-09-22. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ↑ Warren T. Snodgrass (2013-05-13). Pediatric Urology: Evidence for Optimal Patient Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-1-4614-6910-0. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Bush N, Snodgrass W (August 2014). "Response to "Re: Snodgrass W, et al. Duration of follow-up to diagnose hypospadias urethroplasty complications. J Pediatr Urol 2014;10:783-784"". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 10 (4): 784–5. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.04.022. PMID 24999242.

- ↑ Kaplan GW (September 2008). "Does administration of transdermal dihydrotestosterone gel before hypospadias repair improve postoperative outcomes?". Nature Clinical Practice. Urology. 5 (9): 474–5. doi:10.1038/ncpuro1178. PMID 18679395.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Snodgrass WT, Bush N, Cost N (August 2010). "Tubularized incised plate hypospadias repair for distal hypospadias". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 6 (4): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.09.010. PMID 19837000.

- ↑ Wilkinson DJ, Farrelly P, Kenny SE (June 2012). "Outcomes in distal hypospadias: a systematic review of the Mathieu and tubularized incised plate repairs". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 8 (3): 307–12. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.11.008. PMID 21159560.

- ↑ Castagnetti M, El-Ghoneimi A (October 2010). "Surgical management of primary severe hypospadias in children: systematic 20-year review". The Journal of Urology. 184 (4): 1469–74. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.044. PMID 20727541.

- ↑ Warren T. Snodgrass (2013-05-13). Pediatric Urology: Evidence for Optimal Patient Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-4614-6910-0. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ↑ Suoub M, Dave S, El-Hout Y, Braga LH, Farhat WA (October 2008). "Distal hypospadias repair with or without foreskin reconstruction: A single-surgeon experience". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 4 (5): 377–80. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2008.01.215. PMID 18790424.

- ↑ Snodgrass W, Dajusta D, Villanueva C, Bush N (August 2013). "Foreskin reconstruction does not increase urethroplasty or skin complications after distal TIP hypospadias repair". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 9 (4): 401–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.06.008. PMID 22854388.

- ↑ Gatti, John M. "Epidemiology". Medscape Reference. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

Further reading

- Austin PF, Siow Y, Fallat ME, Cain MP, Rink RC, Casale AJ (October 2002). "The relationship between müllerian inhibiting substance and androgens in boys with hypospadias". The Journal of Urology. 168 (4 Pt 2): 1784–8, discussion 1788. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64413-8. PMID 12352359.

- Patel RP, Shukla AR, Snyder HM (October 2004). "The island tube and island onlay hypospadias repairs offer excellent long-term outcomes: a 14-year followup". The Journal of Urology. 172 (4 Pt 2): 1717–9, discussion 1719. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000138903.20136.22. PMID 15371798.

- Retik AB, Atala A (May 2002). "Complications of hypospadias repair". The Urologic Clinics of North America. 29 (2): 329–39. doi:10.1016/S0094-0143(02)00026-5. PMID 12371224.

- Shukla AR, Patel RP, Canning DA (August 2004). "Hypospadias". The Urologic Clinics of North America. 31 (3): 445–60, viii. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2004.04.020. PMID 15313054.

- International Trends in Rates of Hypospadias and Cryptorchidism

- Uretheral graft technique (Camillo Il Grande) Archived 2008-10-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Special issue on hypospadias". Indian Journal of Urology. 24 (2). 2008. Archived from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Congenital disorders of urinary system

- Congenital disorders of male genital organs

- Penis

- Intersex variations

- RTT