Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease

| Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Pelizaeus Merzbacher brain sclerosis[1] | |

| |

| Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease is inherited in an x-linked recessive manner[2] | |

Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease is an X-linked neurological disorder that damages oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system. It is caused by mutations in proteolipid protein 1 (PLP1), a major myelin protein. It is characterized by a decrease in the amount of insulating myelin surrounding the nerves (hypomyelination) and belongs to a group of genetic diseases referred to as leukodystrophies.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The hallmark signs and symptoms of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease include little or no movement in the arms or legs, respiratory difficulties, and characteristic horizontal movements of the eyes left to right.[citation needed]

The onset of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease is usually in early infancy. The most characteristic early signs are nystagmus (rapid, involuntary, rhythmic motion of the eyes) and low muscle tone. Motor abilities are delayed or never acquired, mostly depending upon the severity of the mutation. Most children with Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease learn to understand language, and usually have some speech. Other signs may include tremor, lack of coordination, involuntary movements, weakness, unsteady gait, and over time, spasticity in legs and arms. Muscle contractures often occur over time. Mental functions may deteriorate. Some patients may have convulsions and skeletal deformation, such as scoliosis, resulting from abnormal muscular stress on bones.[citation needed]

Cause

Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease is caused by X-linked recessive mutations in the major myelin protein proteolipid protein 1 (PLP1). This causes hypomyelination in the central nervous system and severe neurological disease. [4][5]

The majority of mutations result in duplications of the entire PLP1 gene. Deletions of PLP1 locus (which are rare) cause a milder form of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease than is observed with the typical duplication mutations, which demonstrates the critical importance of gene dosage at this locus for normal CNS function.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

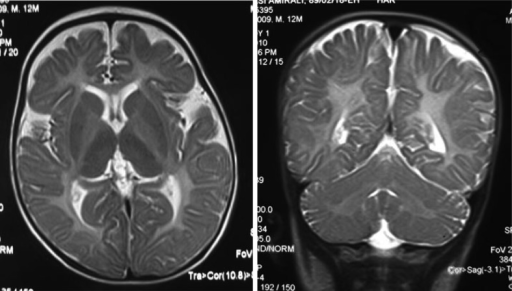

The diagnosis of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease is often first suggested after identification by magnetic resonance imaging of abnormal white matter (high T2 signal intensity, i.e. T2 lengthening) throughout the brain, which is typically evident by about 1 year of age, but more subtle abnormalities should be evident during infancy.

Unless a family history consistent with sex-linked inheritance exists, the condition is often misdiagnosed as cerebral palsy. Once a PLP1 mutation is identified, prenatal diagnosis or preimplantation genetic diagnostic testing is possible.[citation needed]

-

Iso intensity in bilateral periventricular deep white matter

-

Left- MRI,abnormal high signal internal capsule,Right MRI,high signal white matter of cerebellum

Classification

The disease is one in a group of genetic disorders collectively known as leukodystrophies that affect the growth of the myelin sheath, the fatty covering—which acts as an insulator—on nerve fibers in the central nervous system. The several forms of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease include classic, congenital, transitional, and adult variants.[1]

Milder mutations of the PLP1 gene that mainly cause leg weakness and spasticity, with little or no cerebral involvement, are classified as spastic paraplegia 2 (SPG2).[citation needed]

Treatment

No cure for Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease has been developed.[6] Outcomes are variable: people with the most severe form of the disease do not usually survive to adolescence, although with milder forms, survival into adulthood is possible.[6]

Research

In December 2008, StemCells, Inc received clearance in the United States to conduct a phase I clinical trials of human neural stem cell transplantation.[7] The trial did not show meaningful efficacy and the company has since gone bankrupt.[8]

In 2019 Paul Tesar used CRISPR and antisense therapy in a mouse model of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher with success.[9][10][11] Iron chelation as a potential treatment is also being studied.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (Concept Id: C0205711) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-10-29. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 312080 - Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease; PMD". omim.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Hobson, Grace; Garbern, James (2012). "Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-Like Disease 1, and Related Hypomyelinating Disorders". Seminars in Neurology. 32 (1): 062–067. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1306388. ISSN 0271-8235. PMID 22422208.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Inoue, Ken (2017). "Cellular Pathology of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease Involving Chaperones Associated with Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress". Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 4. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2017.00007/full. ISSN 2296-889X. Archived from the original on 2024-04-04. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ↑ Singh, Raman; Samanta, Debopam (2024). "Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2023-05-12. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 2019-10-26. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ↑ "Stem Cells, Inc". Archived from the original on 2019-10-26. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ↑ "End of line for StemCells Inc., pioneering & controversial stem cell biotech". 2016-05-31. Archived from the original on 2019-10-26. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ↑ Elitt, Matthew S.; Barbar, Lilianne; Shick, H. Elizabeth; Powers, Berit E.; Maeno-Hikichi, Yuka; Madhavan, Mayur; Allan, Kevin C.; Nawash, Baraa S.; Nevin, Zachary S.; Olsen, Hannah E.; Hitomi, Midori; LePage, David F.; Jiang, Weihong; Conlon, Ronald A.; Rigo, Frank; Tesar, Paul J. (31 December 2018). "Therapeutic suppression of proteolipid protein rescues Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease in mice". bioRxiv: 508192. doi:10.1101/508192.

- ↑ Elitt, Matthew S.; Barbar, Lilianne; Shick, H. Elizabeth; Powers, Berit E.; Maeno-Hikichi, Yuka; Madhavan, Mayur; Allan, Kevin C.; Nawash, Baraa S.; Gevorgyan, Artur S.; Hung, Stevephen; Nevin, Zachary S.; Olsen, Hannah E.; Hitomi, Midori; Schlatzer, Daniela M.; Zhao, Hien T.; Swayze, Adam; Lepage, David F.; Jiang, Weihong; Conlon, Ronald A.; Rigo, Frank; Tesar, Paul J. (2020-07-01). "Suppression of proteolipid protein rescues Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease". Nature. 585 (7825): 397–403. Bibcode:2020Natur.585..397E. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2494-3. PMC 7810164. PMID 32610343.

- ↑ "Research finds new approach to treating certain neurological diseases". MedicalXpress. 1 July 2020. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

Their research was published online July 1 in the journal Nature. "The pre-clinical results were profound. PMD mouse models that typically die within a few weeks of birth were able to live a full lifespan after treatment," said Paul Tesar

- ↑ Nobuta, Hiroko; Yang, Nan; Ng, Yi Han; Marro, Samuele G.; Sabeur, Khalida; Chavali, Manideep; Stockley, John H.; Killilea, David W.; Walter, Patrick B.; Zhao, Chao; Huie, Philip; Goldman, Steven A.; Kriegstein, Arnold R.; Franklin, Robin J.M.; Rowitch, David H.; Wernig, Marius (October 2019). "Oligodendrocyte Death in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease Is Rescued by Iron Chelation". Cell Stem Cell. 25 (4): 531–541.e6. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2019.09.003. PMID 31585094.

Further reading

- Uhlenberg, Birgit; Schuelke, Markus; Rüschendorf, Franz; Ruf, Nico; Kaindl, Angela M.; Henneke, Marco; Thiele, Holger; Stoltenburg-Didinger, Gisela; Aksu, Fuat; Topaloğlu, Haluk; Nürnberg, Peter; Hübner, Christoph; Weschke, Bernhard; Gärtner, Jutta (August 2004). "Mutations in the Gene Encoding Gap Junction Protein α12 (Connexin 46.6) Cause Pelizaeus-Merzbacher–Like Disease". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1086/422763. PMC 1216059. PMID 15192806.

External links

- Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease Archived 2008-10-07 at the Wayback Machine. NINDS/National Health Institutes.

- pmd at NIH/UW GeneTests

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from October 2020

- Lipid storage disorders

- Leukodystrophies

- X-linked recessive disorders

- Rare diseases

- Demyelinating diseases of CNS