Papaverine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /pəˈpævəriːn/ |

| Trade names | Pavabid, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Vasodilator[1] |

| Main uses | Arterial spasm, erectile dysfunction (ED)[1] |

| Side effects | Nausea, constipation, headache, abdominal pain, flushing, low blood pressure, priapism[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, intravenous, intramuscular, rectal, intracavernosal |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682707 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 80% |

| Protein binding | ~90% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5–2 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

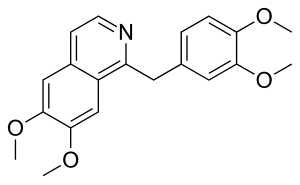

| Formula | C20H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 339.391 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Papaverine is a medication primarily used to treat arterial spasm and erectile dysfunction (ED).[1] It is not a first line agent for ED.[1] Other uses have include painful periods and gastrointestinal spasms.[1] It is given by mouth or by injection.[1] Onset is relatively rapid and lasts for hours.[1]

Common side effects include nausea, constipation, headache, abdominal pain, flushing, low blood pressure, and priapism.[1] Other side effects may include respiratory arrest, liver problems, abuse, and arrhythmia.[1] Safety in pregnancy is unclear.[2]

Papaverine was first isolated in 1848 from opium.[3] Despite being from opium it contains no opioid activity.[4] In the United States a 60 mg dose costs about 40 USD as of 2021.[5]

Medical uses

Papaverine is approved to treat spasms of the gastrointestinal tract, bile ducts and ureter and for use as a cerebral and coronary vasodilator in subarachnoid hemorrhage (combined with balloon angioplasty)[6] and coronary artery bypass surgery.[7] Papaverine may also be used as a smooth muscle relaxant in microsurgery where it is applied directly to blood vessels.

Papaverine is used as an erectile dysfunction drug, alone or sometimes in combination.[8][9] Papaverine, when injected in penile tissue, causes direct smooth muscle relaxation and consequent filling of the corpus cavernosum with blood resulting in erection. A topical gel is also available for ED treatment.[10]

It is also commonly used in cryopreservation of blood vessels along with the other glycosaminoglycans and protein suspensions.[11][12] Functions as a vasodilator during cryopreservation when used in conjunction with verapamil, phentolamine, nifedipine, tolazoline or nitroprusside.[13][14]

Papaverine is also being investigated as a topical growth factor in tissue expansion with some success.[15]

Papaverine is used as an off-label prophylaxis (preventative) of migraine headaches.[16][17][18] It is not a first line drug such as a few beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and some anticonvulsants such as divalproex, but rather when these first line drugs and secondary drugs such as SSRIs, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, etc. fail in the prophylaxis of migraines, have intolerable side effects or are contraindicated.

Papaverine is also present in combinations of opium alkaloid salts such as papaveretum (Omnopon, Pantopon) and others, along with morphine, codeine, and in some cases noscapine and others in a percentage similar to that in opium, or modified for a given application.

Papaverine is found as a contaminant in some heroin[19] and can be used by forensic laboratories in heroin profiling to identify its source.[20] The metabolites can also be found in the urine of heroin users, allowing street heroin to be distinguished from pharmaceutical diacetylmorphine.[21]

Dosage

For arterial spasm it is taken by mouth mouth at a dose of 150 to 300 mg twice per day.[1] Or by injection at 30 mg to 120 mg.[1] For ED a dose of 2.5 to 37.5 mg is used.[1]

Side effects

Frequent side effects of papaverine treatment include polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, constipation, interference with sulphobromophthalein[22] retention test (used to determine hepatic function), increased transaminase levels, increased alkaline phosphatase levels, somnolence, and vertigo.

Rare side effects include flushing of the face, hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating), cutaneous eruption, arterial hypotension, tachycardia, loss of appetite, jaundice, eosinophilia, thrombopenia, mixed hepatitis, headache, allergic reaction, chronic active hepatitis, and paradoxical aggravation of cerebral vasospasm.[23]

Papaverine in the plant Sauropus androgynus is linked to bronchiolitis obliterans.[24]

Mechanism

The in vivo mechanism of action is not entirely clear, but an inhibition of the enzyme phosphodiesterase causing elevation of cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP[clarification needed] levels is significant. It may also alter mitochondrial respiration.

Papaverine has also been demonstrated to be a selective phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the PDE10A subtype found mainly in the striatum of the brain. When administered chronically to mice, it produced motor and cognitive deficits and increased anxiety, but conversely may produce an antipsychotic effect,[25][26] although not all studies support this view.[27]

History

Papaverine was discovered in 1848 by Georg Merck (1825–1873).[28] Merck was a student of the German chemists Justus von Liebig and August Hofmann, and he was the son of Emanuel Merck (1794–1855), founder of the Merck corporation, a major German chemical and pharmaceutical company.[29]

Society and culture

The name "papaverine" is from Latin papaver meaning "poppy".

Names

Papaverine is available as a conjugate of hydrochloride, codecarboxylate, adenylate, and teprosylate. It was also once available as a salt of hydrobromide, camsylate, cromesilate, nicotinate, and amygdalic acid|phenylglycolate. The hydrochloride salt is available for intramuscular, intravenous, rectal and oral administration. The teprosylate is available in intravenous, intramuscular, and orally administered formulations. The codecarboxylate is available in oral form, only, as is the adenylate.

The codecarboxylate is sold under the name Albatran,[30] the adenylate as Dicertan,[31] and the hydrochloride salt is sold variously as Artegodan (Germany), Cardioverina (countries outside Europe and the United States), Dispamil (countries outside Europe and the United States), Opdensit (Germany), Panergon (Germany), Paverina Houde (Italy, Belgium), Pavacap (United States), Pavadyl (United States), Papaverine (Israel), Papaverin-Hamelin (Germany), Paveron (Germany), Spasmo-Nit (Germany), Cardiospan, Papaversan, Cepaverin, Cerespan, Drapavel, Forpaven, Papalease, Pavatest, Paverolan, Therapav (Canada[32]), Vasospan, Cerebid, Delapav, Dilaves, Durapav, Dynovas, Optenyl, Pameion, Papacon, Pavabid, Pavacen, Pavakey, Pavased, Pavnell, Alapav, Myobid, Vasal, Pamelon, Pavadel, Pavagen, Ro-Papav, Vaso-Pav, Papanerin-hcl, Qua bid, Papital T.R., Paptial T.R., Pap-Kaps-150.[33] In Hungary, papaverine and homatropine methylbromide are used in mild drugs that help "flush" the bile.[34]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 "Papaverine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ "DailyMed - PAPAVERINE HYDROCHLORIDE injection, solution". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Hanessian, Stephen (18 December 2013). Natural Products in Medicinal Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 227. ISBN 978-3-527-67655-2. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Sdrales, Lorraine M.; Miller, Ronald D. (21 May 2012). Miller's Anesthesia Review: Expert Consult - Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4377-2793-7. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ "Papaverine Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Liu JK, Couldwell WT (2005). "Intra-arterial papaverine infusions for the treatment of cerebral vasospasm induced by aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage". Neurocrit Care. 2 (2): 124–32. doi:10.1385/NCC:2:2:124. PMID 16159054. S2CID 35400205.

- ↑ Takeuchi K, Sakamoto S, Nagayoshi Y, Nishizawa H, Matsubara J (November 2004). "Reactivity of the human internal thoracic artery to vasodilators in coronary artery bypass grafting". Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 26 (5): 956–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.07.047. PMID 15519189.

- ↑ Desvaux, P (2005). "An overview of the management of erectile disorders". Presse Médicale. 34 (13 Suppl): 5–7. PMID 16158020.

- ↑ Bella, A. J.; Brock, G. B. (2004). "Intracavernous Pharmacotherapy for Erectile Dysfunction". Endocrine. 23 (2–3): 149–155. doi:10.1385/ENDO:23:2-3:149. PMID 15146094. S2CID 13056029.

- ↑ Kim, E.; Elrashidy, R.; McVary, K. (1995). "Papaverine Topical Gel for Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction". The Journal of Urology. 153 (2): 361–5. doi:10.1097/00005392-199502000-00019. PMID 7815584.

- ↑ Müller-Schweinitzer E, Ellis P (May 1992). "Sucrose promotes the functional activity of blood vessels after cryopreservation in DMSO-containing fetal calf serum". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 345 (5): 594–7. doi:10.1007/bf00168954. PMID 1528275. S2CID 10441842.

- ↑ Müller-Schweinitzer E, Hasse J, Swoboda L (1993). "Cryopreservation of human bronchi". J Asthma. 30 (6): 451–7. doi:10.3109/02770909309056754. PMID 8244915.

- ↑ Brockbank KG (February 1994). "Effects of cryopreservation upon vein function in vivo". Cryobiology. 31 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1006/cryo.1994.1009. PMID 8156802.

- ↑ Giglia JS, Ollerenshaw JD, Dawson PE, Black KS, Abbott WM (November 2002). "Cryopreservation prevents arterial allograft dilation". Ann Vasc Surg. 16 (6): 762–7. doi:10.1007/s10016-001-0072-1. PMID 12391500. S2CID 24777062.

- ↑ Tang Y, Luan J, Zhang X (2004). "Accelerating tissue expansion by application of topical papaverine cream". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 114 (5): 1166–9. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000135854.48570.76. PMID 15457029.

- ↑ Sillanpää, M; Koponen, M (1978). "Papaverine in the prophylaxis of migraine and other vascular headache in children". Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica. 67 (2): 209–12. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1978.tb16304.x. PMID 343489. S2CID 28817628.

- ↑ Vijayan, N. (1977). "Brief therapeutic report: papaverine prophylaxis of complicated migraine". Headache. 17 (4): 159–162. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1977.hed1704159.x. PMID 893088. S2CID 36626189.

- ↑ Poser, C. M. (1974). "Letter: Papaverine in prophylactic treatment of migraine". Lancet. 1 (7869): 1290. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(74)90045-2. PMID 4134173.

- ↑ Paterson, S; Cordero, R (2006). "Comparison of the various opiate alkaloid contaminants and their metabolites found in illicit heroin with 6-monoacetyl morphine as indicators of heroin ingestion". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 30 (4): 267–73. doi:10.1093/jat/30.4.267. PMID 16803666.

In addition to morphine, street heroin contains various alkaloids extracted from the opium poppy, Papaversomniferum, including codeine, thebaine, noscapine, and papaverine

- ↑ Seetohul, L. N; Maskell, P. D; De Paoli, G; Pounder, D. J (2013). "Biomarkers for Illicit Heroin: A Previously Unrecognized Origin of Papaverine". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 37 (2): 133. doi:10.1093/jat/bks099. PMID 23316026.

- ↑ Strang, John; Metrebian, Nicola; Lintzeris, Nicholas; Potts, Laura; Carnwath, Tom; Mayet, Soraya; Williams, Hugh; Zador, Deborah; Evers, Richard (May 2010). "Supervised injectable heroin or injectable methadone versus optimised oral methadone as treatment for chronic heroin addicts in England after persistent failure in orthodox treatment (RIOTT): a randomised trial". The Lancet. 375 (9729): 1885–1895. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60349-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 20511018. S2CID 205958031.

- ↑ "SID 149219 — PubChem Substance Summary". Archived from the original on 2013-12-15. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ Clyde BL, Firlik AD, Kaufmann AM, Spearman MP, Yonas H (April 1996). "Paradoxical aggravation of vasospasm with papaverine infusion following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Case report". J. Neurosurg. 84 (4): 690–5. doi:10.3171/jns.1996.84.4.0690. PMID 8613866. S2CID 1172874. Archived from the original on 2021-10-17. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ Bunawan H, Bunawan SN, Baharum SN, Noor NM (2015). "Sauropus androgynus (L.) Merr. Induced Bronchiolitis Obliterans: From Botanical Studies to Toxicology". Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2015/714158. PMC 4564651. PMID 26413127.

- ↑ Siuciak JA, Chapin DS, Harms JF, et al. (August 2006). "Inhibition of the striatum-enriched phosphodiesterase PDE10A: a novel approach to the treatment of psychosis". Neuropharmacology. 51 (2): 386–96. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.013. PMID 16780899. S2CID 13447370.

- ↑ Hebb AL, Robertson HA, Denovan-Wright EM (May 2008). "Phosphodiesterase 10A inhibition is associated with locomotor and cognitive deficits and increased anxiety in mice". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 18 (5): 339–63. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.08.002. PMID 17913473. S2CID 9621541.

- ↑ Weber M, Breier M, Ko D, Thangaraj N, Marzan DE, Swerdlow NR (May 2009). "Evaluating the antipsychotic profile of the preferential PDE10A inhibitor, papaverine". Psychopharmacology. 203 (4): 723–35. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1419-x. PMC 2748940. PMID 19066855.

- ↑ Merck Georg (1848). "Vorläufige Notiz über eine neue organische Base im Opium" [Preliminary notice of a new organic base in opium]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 66: 125–128. doi:10.1002/jlac.18480660121. Archived from the original on 2014-06-08. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ William H. Brock, Justus von Liebig: The Chemical Gatekeeper (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1997). page 120 Archived 2014-07-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "SID 660773 — PubChem Substance Summary". Archived from the original on 2015-01-23. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ "SID 660767 — PubChem Substance Summary". Archived from the original on 2015-01-23. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ "THERAPAV (PRODUIT PUR) - Détail". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2005. CSST - Service du répertoire toxicologique. (French)

- ↑ "SID 660767 — PubChem Substance Summary — Depositor-Supplied Synonyms: All". Archived from the original on 2015-01-23. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ "Országos Gyógyszerészeti és Élelmezés-egészségügyi Intézet". www.ogyi.hu. Archived from the original on 2015-01-23. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from November 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Antispasmodics

- Bitter compounds

- Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids

- Natural opium alkaloids

- Catechol ethers

- Phosphodiesterase inhibitors

- Vasodilators

- RTT