Osteoblastoma

| Osteoblastoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Osteoblastoma in neck | |

| Symptoms | Dull bone pain.[1] |

| Risk factors | Locally destructive[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging, biopsy[1] |

| Frequency | Rare[2] |

Osteoblastoma is a rare noncancerous bone tumor, of the osteogenic type.[2][3][1] It usually presents with a dull pain in the back.[1]

It has clinical and histologic manifestations similar to those of osteoid osteoma.[4] Therefore, some consider the two tumors to be variants of the same disease,[5] with osteoblastoma representing a giant osteoid osteoma. However, an aggressive type of osteoblastoma has been recognized, making the relationship less clear.[6]

Although similar to osteoid osteoma, it is larger (between 2 and 6 cm).[7]

Generaly, osteoblastomas present between the age of 20 and 40 years.[4] Around 40% are located in the spine, and over half have associated scoliosis.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Osteoblastoma usually presents with a dull pain.[1] In contrast to the pain associated with osteoid osteoma, the pain of osteoblastoma usually is less intense, usually not worse at night, and not relieved readily with salicylates (aspirin and related compounds). If the lesion is superficial, there may be a localized swelling and tenderness. Spinal lesions can cause painful scoliosis, although this is less common with osteoblastoma than with osteoid osteoma. In addition, lesions may mechanically interfere with the spinal cord or nerve roots, producing neurologic deficits. Pain and general weakness are common complaints.[citation needed]

Mechanism

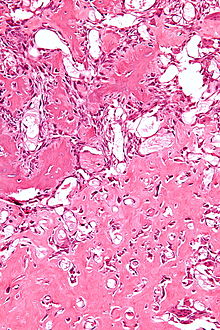

The cause of osteoblastoma is unknown. Histologically, osteoblastomas are similar to osteoid osteomas, producing both osteoid and primitive woven bone amidst fibrovascular connective tissue, the difference being that osteoblastoma can grow larger than 2.0 cm in diameter while osteoid osteomas cannot. Although the tumor is usually considered benign, a controversial aggressive variant has been described in the literature, with histologic features similar to those of malignant tumors such as an osteosarcoma.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

When diagnosing osteoblastoma, the preliminary radiologic workup should consist of radiography of the site of the patient's pain. However, computed tomography (CT) is often necessary to support clinical and plain radiographic findings suggestive of osteoblastoma and to better define the margins of the lesion for potential surgery. CT scans are best used for the further characterization of the lesion with regard to the presence of a nidus and matrix mineralization. MRI aids in detection of nonspecific reactive marrow and soft tissue edema, and MRI best defines soft tissue extension, although this finding is not typical of osteoblastoma. Bone scintigraphy (bone scan) demonstrates abnormal radiotracer accumulation at the affected site, substantiating clinical suspicion, but this finding is not specific for osteoblastoma.[citation needed]

Imaging

-

X-ray: osteoblastoma causing bent spine

-

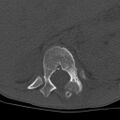

CT scan axial view: expansile osteoblastoma spine

-

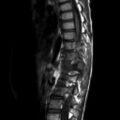

MRI scan osteoblastoma spine

Biopsy

A biopsy is usually required to confirm diagnosis.[1]

Treatment

The first route of treatment in Osteoblastoma is via medical means. Although necessary, radiation therapy (or chemotherapy) is controversial in the treatment of osteoblastoma. Cases of postirradiation sarcoma have been reported after use of these modalities. However, it is possible that the original histologic diagnosis was incorrect and the initial lesion was an osteosarcoma, since histologic differentiation of these two entities can be very difficult.[citation needed]

The alternative means of treatment consists of surgical therapy. The treatment goal is complete surgical excision of the lesion.[8] The type of excision depends on the location of the tumor.

- For stage 1 and 2 lesions, the recommended treatment is extensive intralesional excision, using a high-speed burr. Extensive intralesional resections ideally consist of removal of gross and microscopic tumor and a margin of normal tissue.

- For stage 3 lesions, wide resection is recommended because of the need to remove all tumor-bearing tissue. Wide excision is defined here as the excision of tumor and a circumferential cuff of normal tissue around the entity. This type of complete excision is usually curative for osteoblastoma.

In most patients, radiographic findings are not diagnostic of osteoblastoma; therefore, further imaging is warranted. CT examination performed with the intravenous administration of contrast agent poses a risk of an allergic reaction to contrast material.

The lengthy duration of an MRI examination and a history of claustrophobia in some patients are limiting the use of MRI. Although osteoblastoma demonstrates increased radiotracer accumulation, its appearance is nonspecific, and differentiating these lesions from those due to other causes involving increased radiotracer accumulation in the bone is difficult. Therefore, bone scans are useful only in conjunction with other radiologic studies and are not best used alone.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

Generaly, osteoblastomas present between the age of 20 and 40 years.[4] Around 40% are located in the spine, and over half have associated scoliosis.[4]

In the US, osteoblastomas account for only 0.5-2% of all primary bone tumors and only 14% of benign bone tumors making it a relatively rare form of bone tumor.[citation needed]

In regards to morbidity and mortality, conventional osteoblastoma is a benign lesion with little associated morbidity. However, the tumor may be painful, and spinal lesions may be associated with scoliosis and neurologic manifestations. Metastases and even death have been reported with the controversial aggressive variant, which can behave in a fashion similar to that of osteosarcoma. This variant is also more likely to recur after surgery than is conventional osteoblastoma.[citation needed]

Osteoblastoma affects more males than it does females, with a ratio of 2–3:1 respectively. Osteoblastoma can occur in persons of any age, although the tumors predominantly affect the younger population (around 80% of these tumors occurs in persons under the age of 30). No racial predilection is recognized.[citation needed]

It usually presents in the vertebral column or long bones.[9][10] The tumors usually involve the posterior elements, and 17% of spinal osteoblastomas are found in the sacrum. The long tubular bones are another common site of involvement, with a lower extremity preponderance. Osteoblastoma of the long tubular bones is often diaphyseal, and fewer are located in the metaphysis. Epiphyseal involvement is extremely rare. Although other sites are rarely affected, several bones in the abdomen and extremities have been reported as sites of osteoblastoma tumors.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Bone tumours. What are Bone Tumours?". patient.info. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "Osteoblastoma". Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 3 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. pp. 397–399. ISBN 978-92-832-4503-2. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ↑ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Davies, A. Mark; Sundaram, Murali; James, Steven J. Imaging of Bone Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions: Techniques and Applications. Springer. p. 590. ISBN 978-3-540-77982-7. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ↑ George, Timothy; Daniel H. Kim; Kaufman, Bruce E.; Sean Lew; Narayan Yogananda; Patrick Barnes; Andy Herlich; Deletis, Vedran; Francesco Sala; Frederick Boop; Sigurd Berven; Menezes, Arnold H.; William C. Oakes; Keith Aronyk; Vaccaro, Alexander R. (2007). Surgery of the Pediatric Spine. Thieme New York. p. 312. ISBN 978-1-58890-342-6.

- ↑ Limaiem, Faten; Byerly, Doug W.; Singh, Rahulkumar (2021). "Osteoblastoma". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725639. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ↑ Rubash, Harry E.; Callaghan, John; Rosenberg, Aaron (2007). The adult hip. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 542. ISBN 978-0-7817-5092-9.

- ↑ Max Aebi; Gunzburg, Robert; Szpalski, Marek (2007). Vertebral Tumors. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7817-8867-0.

- ↑ Tugcu B, Gunaldi O, Gunes M, Tanriverdi O, Bilgic B (October 2008). "Osteoblastoma of the temporal bone: a case report". Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 51 (5): 310–2. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1083816. PMID 18855299.

- ↑ Mortazavi SM, Wenger D, Asadollahi S, Shariat Torbaghan S, Unni KK, Saberi S (March 2007). "Periosteal osteoblastoma: report of a case with a rare histopathologic presentation and review of the literature". Skeletal Radiol. 36 (3): 259–64. doi:10.1007/s00256-006-0169-2. PMID 16868789.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |