Orbital blowout fracture

| Blowout fracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Orbital floor fracture | |

| |

| An orbital blowout fracture of the floor of the left orbit. | |

| Specialty | ENT surgery, plastic surgery, ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Double vision, facial numbness, nose bleed, subconjunctival bleed |

| Causes | Direct blow to the eye socket |

An orbital blowout fracture is a traumatic deformity of the orbital floor or medial wall that typically results from the impact of a blunt object larger than the orbital aperture, or eye socket.[1] Most commonly this results in a herniation of orbital contents through the orbital fractures.[1] The proximity of maxillary and ethmoidal sinus increases the susceptibility of the floor and medial wall for the orbital blowout fracture in these anatomical sites.[2] Most commonly, the inferior orbital wall, or the floor, is likely to collapse, because the bones of the roof and lateral walls are robust.[2] Although the bone forming the medial wall is the thinnest, it is buttressed by the bone separating the ethmoidal air cells.[2] The comparatively thin bone of the floor of the orbit and roof of the maxillary sinus has no support and so the inferior wall collapses mostly. Therefore, medial wall blowout fractures are the second-most common, and superior wall, or roof and lateral wall, blowout fractures are uncommon and rare, respectively. They are characterized by double vision, sunken ocular globes, and loss of sensation of the cheek and upper gums from infraorbital nerve injury.[3]

The two broad categories of blowout fractures are open door and trapdoor fractures. Open door fractures are large, displaced and comminuted, and trapdoor fractures are linear, hinged, and minimally displaced.[4] The hinged orbital blowout fracture is a fracture with an edge of the fractured bone attached on either side.[5]

In pure orbital blowout fractures, the orbital rim (the most anterior bony margin of the orbit) is preserved, but with impure fractures, the orbital rim is also injured. With the trapdoor variant, there is a high frequency of extra-ocular muscle entrapment despite minimal signs of external trauma, a phenomenon that is referred to as a "white-eyed" orbital blowout fracture.[3] The fractures can occur of pure floor, pure medial wall or combined floor and medial wall.They can occur with other injuries such as transfacial Le Fort fractures or zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures. The most common causes are assault and motor vehicle accidents. In children, the trapdoor subtype are more common.[6] Smaller fractures are associated with a higher risk of entrapment of the nerve and therefore often smaller fracture are more serious injuries. Large orbital floor fractures have less chance of restrictive strabismus due to nerve entrapment but a greater chance of enopthalmus

There are a lot of controversies in the management of orbital fractures. the controversies debate on the topics of timing of surgery, indications for surgery, and surgical approach used.[4] Surgical intervention may be required to prevent diplopia and enophthalmos. Patients not experiencing enophthalmos or diplopia and having good extraocular mobility may be closely followed by ophthalmology without surgery.[7]

Signs and symptoms

Some clinically observed signs and symptoms include:[8][9]

- Eye pain

- Eyes displaced posteriorly into sockets (enophthalmos)

- Limitation of eye movement (restrictive strabismus)

- Loss of sensation along the trigeminal (V2) nerve distribution

- Seeing-double when looking up or down (vertical diplopia)

- Orbital and lid subcutaneous emphysema, especially when blowing the nose or sneezing

- Nausea and bradycardia due to oculocardiac reflex

- Inability to elevate eye ball, and move eyeball downward due to inferior rectus entrapment

- Bruising/ecchymosis

- Decreased movement of eyes

- Cranial nerve palsies (III, IV, VI)

- subconjunctival hemorrhage

Causes

Common medical causes of blowout fracture may include:[10]

- Direct orbital blunt injury

- Sports injury (squash ball,[11] tennis ball etc.)

- Motor vehicle accidents

- Falls

- Assault

- sports

- work-related injuries

- Any source of direct force

Mechanism

There are two main theories to how orbital fractures occur. The first theory is the hydraulic theory. The hydraulic theory states that a force is applied to the globe which results in equatorial expansion of the globe due to increasing hydrostatic pressure.[10] The pressure is eventually released at the weaker point in the orbit (the medial and inferior walls). Theoretically, this mechanism should lead to more fractures of the medial wall than the floor, since the medial wall is slightly thinner (0.25 mm vs 0.50 mm).[12] However, it is known that pure blowout fractures most frequently involve the orbital floor. This may be attributed to the honeycomb structure of the numerous bony septa of the ethmoid sinuses, which support the lamina papyracea, thus allowing it to withstand the sudden rise in intraorbital hydraulic pressure better than the orbital floor.[13]

The second prevailing theory is known as the buckling theory. The buckling theory states that a force is transmitted directly to the facial skeleton and then a ripple effect is transmitted to the orbit and causes buckling at the weakest points as described above.[10]

In children, the flexibility of the actively developing floor of the orbit fractures in a linear pattern that snaps backward. This is commonly referred to as a trapdoor fracture.[7] The trapdoor can entrap soft-tissue contents, thus causing permanent structural change that requires surgical intervention.[7]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and medical imaging. Periorbital bruising and subconjunctival hemorrhage are indirect signs of a possible fracture.

Imaging

Thin cut (2-3mm) CT scan with axial and coronal view is the optimal study of choice for orbital fractures.[14][15]

Plain radiographs, on the other hand, do not have the sensitively capture blowout fractures.[16] On Water's view radiograph, polypoid mass can be observed hanging from the floor into the maxillary antrum, known as the "teardrop sign", as it usually is in shape of a teardrop. This polypoid mass consists of herniated orbital contents, periorbital fat and inferior rectus muscle. The affected sinus is partially opacified on radiograph. Air-fluid level in maxillary sinus may sometimes be seen due to presence of blood. Lucency in orbits (on a radiograph) usually indicate orbital emphysema.[4]

-

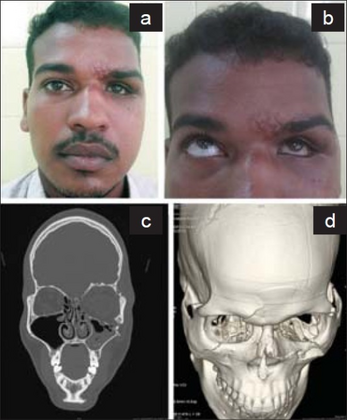

a)Enophthalmos and hypoglobus in left eye, b) restricted left eyeball movement in upward gaze, c) blow out fracture of left orbital floor d) fracture and outward displaced left orbital floor

-

Orbital blowout fracture demonstrating enophthalmos

Anatomy

The bony orbital anatomy is composed of 7 bones: the maxillary, zygomatic, frontal, lacrimal, sphenoid, palatine, and ethmoidal.[17] The floor of the orbit is the roof of the maxillary sinus.[18] The medial wall of the orbit is the lateral wall of the ethmoid sinus. The medial wall is also known as the lamina papyrcea which means "paper layer." This demonstrates the thinness which is associated with increased fractures.[17] The clinically important structures surrounding the orbit include the optic nerve at the apex of the orbit as well as the superior orbital fissure which contains cranial nerves 3, 4, and 6 therefore controlling ocular muscles of eye movement.[18] Inferior to the orbit is the infraorbital nerve which is purely sensory. Five cranial nerves (optic, oculomotor, trochlear, trigeminal, and abducens), and several vascular bundles, pass through the orbital socket.[17]

Treatment

Ophthalmologist follow up is recommended within 1 week of the fracture. To prevent air within the orbit people are advised to avoid blowing of the nose.[14] Nasal decongestants are commonly used. It is also common practice to administer prophylactic antibiotics when the fracture enters a sinus, although this practice is largely anecdotal.[8][19] Amoxicillin-clavulanate and azithromycin are most commonly used.[8] Oral corticosteroids are used to decrease swelling.[20]

Surgery

Surgery is indicated if there is enophthalmos greater than 2 mm on imaging, Double vision on primary or inferior gaze, entrapment of extraocular muscles, or the fracture involves greater than 50% of the orbital floor.[8] When not surgically repaired, most blowout fractures heal spontaneously without significant consequence.[21]

Surgical repair of a "blowout" is rarely undertaken immediately; it can be safely postponed for up to two weeks, if necessary, to let the swelling subside. Surgery to treat the fracture generally leaves little or no scarring and the recovery period is usually brief. Ideally, the surgery will provide a permanent cure, but sometimes it provides only partial relief from double vision or a sunken eye.[22] Reconstruction is usually performed with a titanium mesh or porous polyethylene through a transconjunctival or subciliary incision. More recently, there has been success with endoscopic, or minimally invasive, approaches.[23]

Transcutaneous

Transcutaneous surgery can be performed from a variety of surgical incisions.[24] The first is known as the infraciliary incision.[25] This incision has an advantage as the scar is barely perceivable but the disadvantage is that there is a higher rate of ectropion after repair.[26] The next incision can be performed at the lower eyelid crease also known as the sub tarsal. This creates a more visible scar but has a lower risk of ectropion.[25] The final incision option is infraorbital which allows the easiest access to the orbit but results in the most visible scar.[25]

Transconjunctival

The advantage to this approach is direct access to the orbit and there is no skin incision.[25] The disadvantage to this a purported decreased view of the orbit which can be offset with a canthotomy to increase the view of the orbit.[26]

Endosocpic

Endoscopically, transnasal and transantral approaches had been used for reduction and support of fractured medial and inferior walls, respectively enophthalmos was improved in 89% of the endoscopic group and 76% of the external group (NS).[25] The endoscopic group had no significant complications.[27] The external group had ectropions, significant facial scars, extrusion of inserted Medpor, and intra-orbital hematoma.Disadvantage is working towards the globe rather than away with instruments.[28]

Materials for implant[29] are as follow:

- Nylon suprafoil

- Titanium mesh

- Bone graft

- Porous polyethylene sheets

- Reservable materials

- Preformed orbital implant

Epidemiology

Orbital fractures, in general, are more common in men than women. In one study in children, 81% of cases were boys (mean age 12.5 years).[30] In another study in adults, men accounted for 72% of orbital fractures (mean age 81).[31]

History

Orbital floor fractures were investigated and described by MacKenzie in Paris in 1844[15] and the term blow out fracture was coined in 1957 by Smith & Regan,[32] who were investigating injuries to the orbit and resultant inferior rectus entrapment, by placing a hurling ball on cadaverous orbits and striking it with a mallet.In the 1970's an occuplastic surgeon named Putterman described the first reccomendations for surgery. In the 1970's Putterman advocated for repair of virtually no orbital floor fractures and instead promoted watchful waiting for up to six weeks. At the same time the Plastic surgeons put out literature recommending repair of every orbital floor fracture. Now there has been a softening from both sides and an agreeance in the middle.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lerman S (February 1970). "Blowout fracture of the orbit. Diagnosis and treatment". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 54 (2): 90–98. doi:10.1136/bjo.54.2.90. PMC 1207641. PMID 5441785.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Song WK, Lew H, Yoon JS, Oh MJ, Lee SY (February 2009). "Role of medial orbital wall morphologic properties in orbital blow-out fractures". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 50 (2): 495–499. doi:10.1167/iovs.08-2204. PMID 18824729.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Caranci F, Cicala D, Cappabianca S, Briganti F, Brunese L, Fonio P (October 2012). "Orbital fractures: role of imaging". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT, and MR. 33 (5): 385–391. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2012.06.007. PMID 22964404.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Valencia MR, Miyazaki H, Ito M, Nishimura K, Kakizaki H, Takahashi Y (April 2021). "Radiological findings of orbital blowout fractures: a review". Orbit. 40 (2): 98–109. doi:10.1080/01676830.2020.1744670. PMID 32212885. S2CID 214681849.

- ↑ Young SM, Kim YD, Kim SW, Jo HB, Lang SS, Cho K, Woo KI (June 2018). "Conservatively Treated Orbital Blowout Fractures: Spontaneous Radiologic Improvement". Ophthalmology. 125 (6): 938–944. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.12.015. PMID 29398084. S2CID 4700726.

- ↑ Ellis E (November 2012). "Orbital trauma". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 24 (4): 629–648. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2012.07.006. PMID 22981078.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Flint PW, Cummings CW (2010-01-01). Otolaryngology head and neck surgery. Mosby. ISBN 9780323052832. OCLC 664324957.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Jatla KK, Enzenauer RW (2004). "Orbital fractures: a review of current literature". Current Surgery. 61 (1): 25–29. doi:10.1016/j.cursur.2003.08.003. PMID 14972167.

- ↑ Friedman NJ, Pineda II R (2014). The Massachusetts eye and ear infirmary illustrated manual of ophthalmology. ISBN 9781455776443. OCLC 944088986.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Adeyemo WL, Aribaba OT, Ladehinde AL, Ogunlewe MO (December 2008). "Mechanisms of orbital blowout fracture: a critical review of the literature". The Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal. 15 (4): 251–254. PMID 19169343. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ Nickson C (July 26, 2014) [August 8, 2010]. "Blown Out, aka Ophthalmology Befuddler 014". Life in the Fast Lane. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ↑ Phan, Laura T., W. Jordan Piluek, and Timothy J. McCulley. "Orbital trapdoor fractures." Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology (2012).

- ↑ O-Lee, T. J., and Peter J. Koltai. "Pediatric Facial Fractures." Pediatric Otolaryngology for the Clinician (2009): 91-95.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Joseph JM, Glavas IP (January 2011). "Orbital fractures: a review". Clinical Ophthalmology. 5: 95–100. doi:10.2147/opth.s14972. PMC 3037036. PMID 21339801.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ng P, Chu C, Young N, Soo M (August 1996). "Imaging of orbital floor fractures". Australasian Radiology. 40 (3): 264–268. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1673.1996.tb00400.x. PMID 8826732.

- ↑ Brady SM, McMann MA, Mazzoli RA, Bushley DM, Ainbinder DJ, Carroll RB (March 2001). "The diagnosis and management of orbital blowout fractures: update 2001". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 19 (2): 147–154. doi:10.1053/ajem.2001.21315. PMID 11239261.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Turvey TA, Golden BA (November 2012). "Orbital anatomy for the surgeon". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. The Orbit. 24 (4): 525–536. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2012.08.003. PMC 3566239. PMID 23107426.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Felding UN (March 2018). "Blowout fractures - clinic, imaging and applied anatomy of the orbit". Danish Medical Journal. 65 (3): B5459. PMID 29510812. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ Martin B, Ghosh A (January 2003). "Antibiotics in orbital floor fractures". Emergency Medicine Journal. 20 (1): 66. doi:10.1136/emj.20.1.66-a. PMC 1726033. PMID 12533379.

- ↑ Courtney DJ, Thomas S, Whitfield PH (October 2000). "Isolated orbital blowout fractures: survey and review". The British Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 38 (5): 496–504. doi:10.1054/bjom.2000.0500. PMID 11010781.

- ↑ Damgaard OE, Larsen CG, Felding UA, Toft PB, von Buchwald C (September 2016). "Surgical Timing of the Orbital "Blowout" Fracture: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 155 (3): 387–390. doi:10.1177/0194599816647943. PMID 27165680. S2CID 22854098.

- ↑ Mwanza, J. C. K., D. K. Ngoy, and D. L. Kayembe. "Reconstruction of orbital floor blow-out fractures with silicone implant." Bulletin de la Société belge d'ophtalmologie 280 (2001): 57–62.

- ↑ Wilde F, Lorenz K, Ebner AK, Krauss O, Mascha F, Schramm A (May 2013). "Intraoperative imaging with a 3D C-arm system after zygomatico-orbital complex fracture reduction". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 71 (5): 894–910. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2012.10.031. PMID 23352428.

- ↑ Burnstine, Michael A. (October 2003). "Clinical recommendations for repair of orbital facial fractures". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 14 (5): 236–240. doi:10.1097/00055735-200310000-00002. ISSN 1040-8738. PMID 14502049. S2CID 20454732. Archived from the original on 2023-01-26. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Pfeiffer, Margaret L.; Bergman, Mica Y.; Merritt, Helen A.; Samimi, David B.; Dresner, Steven C.; Burnstine, Michael A. (December 2018). "Re: Kersten et al.: Orbital 'blowout' fractures: time for a new paradigm (Ophthalmology. 2018;125:796-798)". Ophthalmology. 125 (12): e87–e88. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.06.030. ISSN 1549-4713. PMID 30343934. S2CID 53041839. Archived from the original on 2023-01-26. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Burnstine, Michael A. (July 2002). "Clinical recommendations for repair of isolated orbital floor fractures: an evidence-based analysis". Ophthalmology. 109 (7): 1207–1210, discussion 1210–1211, quiz 1212–1213. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01057-6. ISSN 0161-6420. PMID 12093637. Archived from the original on 2023-01-26. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ Ducic Y, Verret DJ (June 2009). "Endoscopic transantral repair of orbital floor fractures". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 140 (6): 849–854. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.004. PMID 19467402. S2CID 27346185.

- ↑ Jin HR, Yeon JY, Shin SO, Choi YS, Lee DW (January 2007). "Endoscopic versus external repair of orbital blowout fractures". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 136 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2006.08.027. PMID 17210331. S2CID 20356825.

- ↑ Han, Dae Heon; Chi, Mijung (July 2011). "Comparison of the outcomes of blowout fracture repair according to the orbital implant". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 22 (4): 1422–1425. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e31821cc2b5. ISSN 1536-3732. PMID 21772173. S2CID 9206820. Archived from the original on 2023-01-26. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ Hatton MP, Watkins LM, Rubin PA (May 2001). "Orbital fractures in children". Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 17 (3): 174–179. doi:10.1097/00002341-200105000-00005. PMID 11388382. S2CID 13653675.

- ↑ Manolidis S, Weeks BH, Kirby M, Scarlett M, Hollier L (November 2002). "Classification and surgical management of orbital fractures: experience with 111 orbital reconstructions". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 13 (6): 726–37, discussion 738. doi:10.1097/00001665-200211000-00002. PMID 12457084. S2CID 43630551.

- ↑ "Blowout fracture of the orbit: mechanism and correction of internal orbital fracture. By Byron Smith and William F. Regan, Jr". Advances in Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 6: 197–205. 1987. PMID 3331936.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- CT Scans of Blowout Fracture from MedPix