Nutrition in classical antiquity

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Poor grammar, punctuation, and arrangement of ideas. (April 2021) |

Classical antiquity is the period of cultural history spanning from the 8th century BC to the beginning of the Middle Ages (which began around 500 AD). The major civilizations are those of the Mediterranean region, ancient Greece, ancient Rome, and southwest Asia. Nutrition consisted of simple fresh or preserved whole foods that were either locally grown or transported from neighboring areas during times of crisis. Physicians and philosophers studied the effect of food on the human body and they generally agreed that food was important in preventing illness and restoring health.

Food of antiquity

People ate various types of food; consumers had choices from dairy (milk and cheese), fruits (figs, pears, apples, and pomegranates), vegetables (greens and bulbs), grains and legumes (cereal, wheat barley, millet, beans, and chickpeas), and meat (beef, mutton, fowl, mussels, and oysters).[1][2] Food was most often fresh, but the processing of food aided in the preservation for long-term storage or transport to other cities. Cereals, olives, wine, legumes, vegetables, fruit, and animal products could all be processed and stored for later use.[3] Cereals were often processed and stored in the form of bread, flat-cakes, and porridge.[4] Legumes were also most often processed and stored as pulses and eaten with bread to enhance the flavor.[5] Cereals were most nourishing providing essential macro- and micronutrients to consumers.[6] Cereals sustained individuals with sufficient amounts of protein, vitamin B, vitamin E, calcium, and iron.[7] Fruits and vegetables provided vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin D, and half the dietary fiber needed for health support.[8]

Food shortage

Cities depended on trade with agricultural farmers and neighboring cities for food supply due to the lack of land cultivation area.[9][10] Food supply was altered by numerous events such as climate, location, and distribution.[11] Weather drastically affected the amount of produce harvested during a growing season. Climate often fluctuated in the Mediterranean region with varying temperatures and volumes of precipitation; these two factors also affected the quality of soil available to farmers.[12] Soil composition mainly depended on location, but the climate affected the moisture retained within the soil.[13] If the growing season was not prosperous then cities would have to resort to trade as a means for food supply. This often made food distribution difficult due to political disagreements and issues with transportation.[14] To combat hunger due to inadequate food supply people would eat twigs, roots of plants, bark from trees, and each other as a last resort.[15] Food shortages were frequent but did not last long enough to generate famine.

People of interest

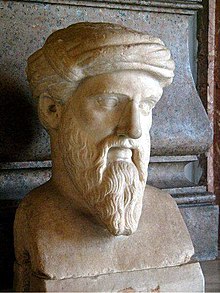

Pythagoras (570 BC – 495 BC) was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, and is also considered to be "the Father of Ethical Vegetarianism". He believed that in order to obtain the highest level of spiritual and physical health it was necessary to follow a lifestyle that included a vegetarian diet which excluded meats and other flesh foods.[16] Anaxagoras (500 BC – 428 BC) was also a Greek philosopher, he suggested that foods that we ate contained fragments that were needed for growth in the body. His belief was that "everything is in everything, at all times", physical characteristics (hair, nails, flesh, etc.) were generated from foods that contained those same substances.[17] Hippocrates (460 BC – 377 BC) was a physician known as the "father of medicine", his nutritional advice was based on the presence of the four humors in the body.[18] Plato (428/427 BC – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher and mathematician; his idea of a healthy diet consisted of balance and moderation of cereals, fruits, vegetables, dairy, with a strong emphasis on the moderation of meat and wine.[19] His belief is that excess food from one source would lead to future ailments. Galen (129 AD – 216 AD) built much of his work by challenging the writings of others. He was an admirer of Hippocrates because of the work he had done in the field of medicine.[20] Galen believed that Hippocrates had stated all that needed to be known about nutrition, and he would interpret his work by the presentation of his own knowledge.[21]

Medicine

The humoral theory of medicine was central to medicine during antiquity and for centuries following. Physicians believed that the body contained a mixture of bodily fluids, the four humors: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. They assessed a patient's degree of health based on the balance of these four bodily fluids. Diet was the first prescribed treatment of disease followed by drugs, then surgery.[22] Early physicians studied the different ways foods would affect the humors of the body by restoring health or causing disease. Utilizing knowledge about how humors were affected by diet physicians prescribed diets with balance, moderation, and timing in mind. Galen worked extensively on classifying foods according to how they interacted with the humors of the body.[23] Galen had also noted that some foods had drug characteristics and for that reason during food preparation it was not uncommon to boil those foods two or three times.[24]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Skiadas, P., & Lascaratos, J. (2001). Dietetics in ancient Greek philosophy: Plato's concepts of healthy diet. Published Online: 14 June 2001; | doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601179, 55(7).

- ^ Thurmond, D. L. (2006). A handbook of food processing in classical Rome: For her bounty no winter(Technology and change in history, v. 9; Technology and change in history, v. 9). Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P.15

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P.15

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P.36

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P.12

- ^ Garnsey, P., & Scheidel, W. (1998). Cities, peasants, and food in classical antiquity : Essays in social and economic history. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P.183

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P. 29 - 33.

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P. 34

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P. 35

- ^ Thurmond, D. L. (2006). A handbook of food processing in classical Rome: For her bounty no winter(Technology and change in history, v. 9; Technology and change in history, v. 9). Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P. 35

- ^ Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. P. 37

- ^ Leitzmann C. (2014). Vegetarian nutrition: past, present, future. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100, 496S-502S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071365

- ^ Sisko, J. E. (2010). Anaxagoras on Matter, Motion, and Multiple Worlds. Philosophy Compass, 5(6), 443-454. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2010.00313.x

- ^ Ullah, M. F., & Khan, M. W. (2008). Food as medicine: potential therapeutic tendencies of plant derived polyphenolic compounds. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev,9(2), 187-196.

- ^ Skiadas, P., & Lascaratos, J. (2001). Dietetics in ancient Greek philosophy: Plato's concepts of healthy diet. Published Online: 14 June 2001; | doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601179, 55(7).

- ^ Jouanna, J., Eijk, P. J. v. d., & Allies, N. (2012).Greek medicine from Hippocrates to Galen: Selected papers(Studies in Ancient Medicine; Studies in ancient medicine). Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Galen, & Grant, M. (2000). Galen: on food and diet. (M. Grant, Trans.). London and New York: Routledge. P. 5

- ^ Galen, & Grant, M. (2000). Galen: on food and diet. (M. Grant, Trans.). London and New York: Routledge. P. 6

- ^ Galen, & Grant, M. (2000). Galen: on food and diet. (M. Grant, Trans.). London and New York: Routledge. P. 11

- ^ Galen, & Grant, M. (2000). Galen: on food and diet. (M. Grant, Trans.). London and New York: Routledge. P. 7

Bibliography

- Galen, & Grant, M. (2000). Galen: on food and diet. (M. Grant, Trans.). London and New York: Routledge.

- Garnsey, P. (1988). Famine and food supply in the Graeco-Roman world : Responses to risk and crisis. Cambridge Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press.

- Garnsey, P. (1999). Food and society in classical antiquity (Key themes in ancient history; Key themes in ancient history). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Garnsey, P., & Scheidel, W. (1998). Cities, peasants, and food in classical antiquity : Essays in social and economic history. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Hamlyn, D.W. [1968] 1993. Aristotle De Anima, Books II and III (with passages from Book I), translated with Introduction and Notes by D.W. Hamlyn, with a Report on Recent Work and a Revised Bibliography by Christopher Shields, Oxford: Clarendon Press. (First edition, 1968.).

- Hippocrates, & Adams, F. (1886). The genuine works of Hippocrates (Wood's library of standard medical authors; Wood's library of standard medical authors). New York: William Wood and Company.

- J. Mira Seo. (2010). Food and Drink, Roman(1. ed.). In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

- Jouanna, J., Eijk, P. J. v. d., & Allies, N. (2012). Greek medicine from Hippocrates to Galen: Selected papers(Studies in Ancient Medicine; Studies in ancient medicine). Leiden: Brill.

- Leitzmann C. (2014). Vegetarian nutrition: past, present, future. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100, 496S-502S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071365

- McLaren, D. S. (1999). Towards the conquest of Vitamin A deficiency disorders. Basel, Switzerland: Task Force Sight and Life.

- Orfanos, C. (2007). HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE: From Hippocrates to modern medicine. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology, 21(6), 852–858.

- Rocca, J. (2003). Galenic dietetics. Early Science And Medicine, 8(1), 44–51.

- Sisko, J. E. (2010). Anaxagoras on Matter, Motion, and Multiple Worlds. Philosophy Compass, 5(6), 443–454. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2010.00313.x

- Skiadas, P., & Lascaratos, J. (2001). Dietetics in ancient Greek philosophy: Plato's concepts of healthy diet. , Published Online: 14 June 2001; | doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601179, 55(7).

- Thurmond, D. L. (2006). A handbook of food processing in classical Rome: For her bounty no winter(Technology and change in history, v. 9; Technology and change in history, v. 9). Leiden: Brill.

- Ullah, M. F., & Khan, M. W. (2008). Food as medicine: potential therapeutic tendencies of plant derived polyphenolic compounds. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev,9(2), 187–196.

- van der Eijk, P. J. (2002). Hippocrates: the protean father of medicine. The Lancet, 359(9325), 2285. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09311-X