Jackhammer esophagus

| Jackhammer esophagus | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Nutcracker esophagus,[1] esophageal hypercontractility,[2] hypercontractile esophagus,[1] nutcracker achalasia | |

| |

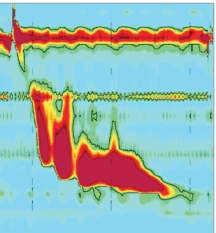

| Jackhammer esophagus with normal distal latency on esophageal high-resolution manometry | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Difficulty swallowing, chest pain[3] |

| Complications | Achalasia[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[3] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, GERD[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Esophageal manometry[2] |

| Treatment | Proton pump inhibitors, hyoscine butylbromide, antidepressants, esophageal dilation, surgery[3] |

| Prognosis | Often resolves with time[3] |

| Frequency | Rare[1] |

Jackhammer esophagus, previously known as nutcracker esophagus, is a condition in which there is excessively strong contractions of the esophagus.[1] Symptoms may include difficulty swallowing, regurgitation, heart burn, and chest pain.[3] Complications may rarely include achalasia.[1]

The cause is unknown.[3] Risk factors include obesity and GERD.[3] While the esophageal contractions are excessive in strength, they remain coordinated.[2] Diagnosis is by esophageal manometry finding a distal contractile integral of more than 8,000 mmHg*s*cm or pressures exceeding 220 mmHg.[2] It is a type of esophageal motility disorder, along with achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm.[2]

Treatment options may include proton pump inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, hyoscine butylbromide, antidepressants, esophageal dilation, and surgery; however, evidence to support these is poor.[3][4] Often the condition resolves without specific measures.[3]

Jackhammer esophagus is rare.[1] It primarily affects those over the age of 60.[1] Males and females are affected equally frequently.[4] The condition was first described in the 1970s.[4] The term "nutcracker esophagus" comes from the increased pressures being likened to that created by a mechanical nutcracker.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Nutcracker esophagus is characterized as a motility disorder of the esophagus, meaning that it is caused by abnormal movement, or peristalsis of the esophagus.[6] People with motility disorders present with two main symptoms: chest pain or difficulty with swallowing. Chest pain is the more common. The chest pain is very severe and intense, and mimics cardiac chest pain.[7][8][9][10] It may spread into the arm and back. The symptoms of nutcracker esophagus are intermittent, and may occur with or without food.[6] Rarely, patients can present with a sudden obstruction of the esophagus after eating food (termed a food bolus obstruction, or the 'steakhouse syndrome') requiring urgent treatment. The disorder does not progress to produce worsening symptoms or complications, unlike other motility disorders (such as achalasia) or anatomical abnormalities of the esophagus (such as peptic strictures or esophageal cancer). Many patients with nutcracker esophagus do not have any symptoms at all, as esophageal manometry studies done on patients without symptoms may show the same motility findings as nutcracker esophagus.[6] Nutcracker esophagus may also be associated with metabolic syndrome. The incidence of nutcracker esophagus in all patients is uncertain.[11][12]

Pathophysiology

Pathology specimens of the esophagus in patients with nutcracker esophagus show no significant abnormality, unlike patients with achalasia, where destruction of the Auerbach's plexus is seen. The pathophysiology of nutcracker esophagus may be related to abnormalities in neurotransmitters or other mediators in the distal esophagus. Abnormalities in nitric oxide levels, which have been seen in achalasia, are postulated as the primary abnormality.[6][13] As GERD is associated with nutcracker esophagus, the alterations in nitric oxide and other released chemicals may be in response to reflux.[14]

Diagnosis

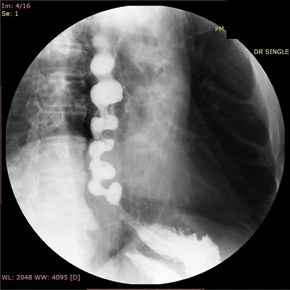

In people who have dysphagia, testing may first be done to exclude an anatomical cause of dysphagia, such as distortion of the anatomy of the esophagus. This usually includes visualization of the esophagus with an endoscope, and can also include barium swallow X-rays of the esophagus. Endoscopy is typically normal in patients with nutcracker esophagus; however, abnormalities associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, which associates with nutcracker esophagus, may be seen.[16] Barium swallow in nutcracker esophagus is also typically normal,[6] but may provide a definitive diagnosis if contrast is given in tablet or granule form. Studies on endoscopic ultrasound show slight trends toward thickening of the muscularis propria of the esophagus in nutcracker esophagus, but this is not useful in making the diagnosis.[17]

Motility studies

Nutcracker esophagus in (C): high-pressure waves in blue; cross-sectional areas (CSA) in fucsia.

The diagnosis of nutcracker esophagus is typically made with an esophageal motility study, which shows characteristic features of the disorder. Esophageal motility studies involve pressure measurements of the esophagus after a patient takes a wet (fluid-containing) or dry (solid-containing) swallow. Measurements are usually taken at various points in the esophagus.[18]

Nutcracker esophagus is characterized by a number of criteria described in the literature. The most commonly used criteria are the Castell criteria, named after American gastroenterologist D.O. Castell. The Castell criteria include one major criterion: a mean peristaltic amplitude in the distal esophagus of more than 180 mm Hg. The minor criterion is the presence of repetitive contractions (meaning two or more) that are greater than six seconds in duration. Castell also noted that the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes normally in nutcracker esophagus, but has an elevated pressure of greater than 40 mm Hg at baseline.[6][18][19][14]

Three other criteria for the definition of the nutcracker esophagus have been defined. The Gothenburg criterion consists of the presence of peristaltic contractions, with an amplitude of 180 mm Hg at any place in the esophagus.[16][14] The Richter criterion involves the presence of peristaltic contractions with an amplitude of greater than 180 mm Hg from an average of measurements taken 3 and 8 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter. It has been incorporated into a number of clinical guidelines for the evaluation of dysphagia.[14] The Achem criteria are more stringent, and are an extension of the study of 93 patients used by Richter and Castell in the development of their criteria, and require amplitudes of greater than 199 mm Hg at 3 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), greater than 172 mm Hg at 8 cm above the LES, or greater than 102 mm Hg at 13 cm above the LES.[14][20]

Treatment

People are usually reassured that the disease is unlikely to worsen. However, the symptoms of chest pain and trouble swallowing may be severe enough to require treatment with medications, and rarely, surgery.

The initial step of treatment focuses on reducing risk factors. While weight reduction may be useful in reducing symptoms, the role of acid suppression therapy to reduce esophageal reflux is still uncertain.[21] Very cold and very hot beverages may trigger esophageal spasms.[22][23]

Medications

Medications for nutcracker esophagus includes the use of calcium-channel blockers, which relax the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and palliate the dysphagia symptoms. Diltiazem, a calcium-channel blocker, has been used in randomized control studies with good effect. Nitrate medications, including isosorbide dinitrate, given before meals, may also help relax the LES and improve symptoms.[6] The inexpensive generic combination of belladonna and phenobarbital (Donnatal and other brands) may be taken three times daily as a tablet to prevent attacks or, for patients with only occasional episodes, as an elixir at the onset of symptoms. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors, such as sildenafil, can be given to reduce symptoms, particularly pain, but small trials have not been able to demonstrate clinical improvement.[24][25]

Procedures

Endoscopic therapy with botulinum toxin can also be used to improve dysphagia which stabilizes unintentional weight loss, but the effect has limited effect on other symptoms, including pain, while also being a temporary treatment lasting a few weeks.[26] Finally, pneumatic dilatation of the esophagus, which is an endoscopic technique where a high-pressure balloon is used to stretch the muscles of the LES, can be performed to improve symptoms, but again no clinical improvement is seen in regards to motility.[27]

In people who have no response to medical or endoscopic therapy, surgery can be performed. A Heller myotomy involves an incision to disrupt the LES and the myenteric plexus that innervates it. The Heller myotomy is used as a final treatment option in patients who do not respond to other therapies.[28]

Prognosis

Nutcracker esophagus is a benign, nonprogressive condition, meaning it is not associated with significant complications.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Wilkinson, JM; Halland, M (1 September 2020). "Esophageal Motility Disorders". American family physician. 102 (5): 291–296. PMID 32866357.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Roman, S; Kahrilas, PJ (March 2013). "Management of spastic disorders of the esophagus". Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 42 (1): 27–43. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2012.11.002. PMID 23452629.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Savarino, E; Smout, AJPM (November 2020). "The hypercontractile esophagus: Still a tough nut to crack". Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 32 (11): e14010. doi:10.1111/nmo.14010. PMID 33043556.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Townsend, Courtney M.; Beauchamp, R. Daniel; Evers, B. Mark; Mattox, Kenneth L. (22 April 2016). Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1016. ISBN 978-0-323-40163-0. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ↑ Madgaonkar, C. S.; CS, Madgaonkar (August 2011). Diagnosis: A Symptom-based Approach in Internal Medicine. JP Medical Ltd. p. 99. ISBN 978-93-80704-75-3. Archived from the original on 2022-07-23. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Tutuian, Radu; Castell, Donald O. (2006). "Esophageal motility disorders (Distal esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, and hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter): Modern management". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 9 (4): 283–94. doi:10.1007/s11938-006-0010-y. PMID 16836947. S2CID 37079411.

- ↑ "Heartburn or Heart Attack? How to Tell the Difference". health.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Esophageal spasms - Symptoms and causes". mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Jr., Harold M. Schmeck (19 January 1989). "HEALTH: SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSIS; When Chest Pains Have Nothing to Do With a Heart Attack". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Heart Attack and Conditions That Mimic Heart Attack: Learn About Chest Pain". www.secondscount.org. 30 November 2008. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Savarino, E; Smoutcorresponding, A (November 2020). "The hypercontractile esophagus: Still a tough nut to crack". Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 32 (11): e14010. doi:10.1111/nmo.14010. PMC 7685127. PMID 33043556.

- ↑ "Nutcracker Esophagus". Healthline. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ↑ Kahrilas, P. J. (2000). "Esophageal motility disorders: Current concepts of pathogenesis and treatment". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (3): 221–31. doi:10.1155/2000/389709. PMID 10758419.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Pilhall, M.; Börjesson, M.; Rolny, P.; Mannheimer, C. (2002). "Diagnosis of nutcracker esophagus, segmental or diffuse hypertensive patterns, and clinical characteristics". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 47 (6): 1381–8. doi:10.1023/A:1015343119090. PMID 12064816. S2CID 20665774.

- ↑ Sirinawasatien, Apichet; Sakulthongthawin, Pallop (December 2021). "Manometrically jackhammer esophagus with fluoroscopically/endoscopically distal esophageal spasm: a case report". BMC Gastroenterology. 21 (1): 222. doi:10.1186/s12876-021-01808-3.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Fang, J; Bjorkman, D (2002). "Nutcracker esophagus: GERD or an esophageal motility disorder". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 97 (6): 1556–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9270(02)04159-X. PMID 12094884.

- ↑ Meizer, Ehud; Ron, Yishay; Tiomni, Elisa; Avni, Yona; Bar-Meier, Simon (1997). "Assessment of the esophageal wall by endoscopic ultrasonography in patients with nutcracker esophagus". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 46 (3): 223–5. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(97)70090-7. PMID 9378208.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Cockeram, A. W. (1998). "Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Practice Guidelines: Evaluation of dysphagia". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (6): 409–13. doi:10.1155/1998/303549. PMID 9784896.

- ↑ Ott, D. J. (1994). "Motility disorders of the esophagus". Radiologic Clinics of North America. 32 (6): 1117–34. PMID 7972703.

- ↑ Achem, S. R.; Kolts, B. E.; Burton, L (1993). "Segmental versus diffuse nutcracker esophagus: An intermittent motility pattern". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 88 (6): 847–51. PMID 8503378.

- ↑ Borjesson, M.; Rolny, P.; Mannheimer, C.; Pilhall, M. (2003). "Nutcracker oesophagus: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of the effects of lansoprazole". Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 18 (11–12): 1129–35. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2306.2003.01788.x. PMID 14653833. S2CID 31592531.

- ↑ "Esophageal spasm: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-01-25. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

- ↑ "Esophageal Spasm Causes, Symptoms, Treatments, and More". Webmd.com. 2011-06-01. Archived from the original on 2013-01-16. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

- ↑ Eherer, A. J.; Schwetz, I; Hammer, H. F.; Petnehazy, T; Scheidl, S. J.; Weber, K; Krejs, G. J. (2002). "Effect of sildenafil on oesophageal motor function in healthy subjects and patients with oesophageal motor disorders". Gut. 50 (6): 758–64. doi:10.1136/gut.50.6.758. PMC 1773249. PMID 12010875.

- ↑ "Sildenafil in Esophageal Motility Disorders". Archived from the original on 2022-07-13. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- ↑ Vanuytsel, Tim; Bisschops, Raf; Farré, Ricard; Pauwels, Ans; Holvoet, Lieselot; Arts, Joris; Caenepeel, Philip; De Wulf, Dominiek; Mimidis, Kostas; Rommel, Nathalie; Tack, Jan (2013). "Botulinum Toxin Reduces Dysphagia in Patients with Nonachalasia Primary Esophageal Motility Disorders". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 11 (9): 1115–1121.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.021. PMID 23591282. Archived from the original on 2022-07-23. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- ↑ "Is there any objective benefit from therapeutic dilatation in patients with nutcracker esophagus ?". Archived from the original on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- ↑ "Achalasia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 14 October 2020. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |