Nipah virus infection

| Nipah virus infection | |

|---|---|

| |

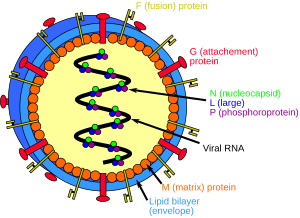

| Structure of a Henipavirus | |

| Symptoms | None, fever, cough, headache, confusion[1] |

| Complications | Inflammation of the brain, seizures[2] |

| Usual onset | 5 to 14 days after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Nipah virus (spread by direct contact)[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, confirmed by laboratory testing[4] |

| Prevention | Avoiding exposure to bats and sick pigs, not drinking raw date palm sap[5] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[2] |

| Frequency | ~701 human cases (1998 to May 2018)[6][7] |

| Deaths | ~40 to 75% risk of death[8][9] |

A Nipah virus infection is a viral infection caused by the Nipah virus.[2] Symptoms from infection vary from none to fever, cough, headache, shortness of breath, and confusion.[1][2] This may worsen into a coma over a day or two.[1] Complications can include inflammation of the brain and seizures following recovery.[2]

The Nipah virus (NiV) is a type of RNA virus in the genus Henipavirus.[2] The virus normally circulates among specific types of fruit bats.[2] It can both spread between people and from other animals to people.[2] Spread typically requires direct contact with an infected source.[3] Diagnosis is based on symptoms and confirmed by laboratory testing.[4]

Management involves supportive care.[2] As of 2023 there is no vaccine or specific treatment.[2] Prevention is by avoiding exposure to bats and sick pigs and not drinking raw date palm sap.[5] As of May 2018 about 700 human cases are estimated to have occurred and 40 to 75% of those who were infected died.[6][8][7][9] In May 2018, an outbreak of the disease resulted in 17 deaths in the Indian state of Kerala.[10][11][12]

The disease was first identified in 1998 during an outbreak in Malaysia while the virus was isolated in 1999.[2][13] It is named after a village in Malaysia, Sungai Nipah.[13] Pigs may also be infected and millions were killed by Malaysian authorities in 1999 to stop the spread of disease.[2][13]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms start to appear after 5–14 days from exposure.[13] Initial symptoms are fever, headache, drowsiness followed by disorientation and mental confusion. These symptoms can progress into coma as fast as in 24–48 hours. Encephalitis, inflammation of the brain, is a potentially fatal complication of Nipah virus infection. Respiratory illness can also be present during the early part of the illness.[13] Nipah-case patients who have breathing difficulty are more likely than those without respiratory illness to transmit the virus,[14] as are those who are more than 45 years of age.[15] The disease is suspected in symptomatic individuals in the context of an epidemic outbreak.

Risks

The risk of exposure is high for hospital workers and caretakers of those infected with the virus. In Malaysia and Singapore, Nipah virus infection occurred in those with close contact to infected pigs. In Bangladesh and India, the disease has been linked to consumption of raw date palm sap (toddy) and eating of fruits partially consumed by bats and using water from wells inhabited by bats.[16][17]

-

How the Nipah virus spreads[18]

-

Fruit bats are the natural reservoirs of Nipah virus

Diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis of Nipah virus infection is made by:

ARN detection can be done using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from throat swabs, cerebrospinal fluid, urine and blood analysis during acute and convalescent stages of the disease.[13]

IgG and IgM antibody detection can be done after recovery to confirm Nipah virus infection. Immunohistochemistry on tissues collected during autopsy also confirms the disease.[13]

-

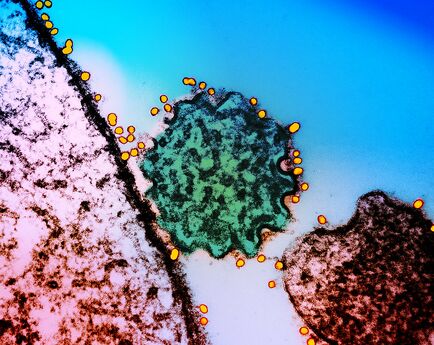

Transmission electron micrograph of a single Nipah virus particle green that has budded from the surface of an infected cell pink. Nipah virus surface glycoproteins have been labeled using a technique called “immunogold labeling,” in which gold particles are bound to antibodies that recognize a specific viral antigen or epitope, which then bind to that individual virus species both within and on the surfaces of infected cell

-

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) depicted a number of Nipah virus virions from a person's cerebrospinal fluid

Prevention

Prevention of Nipah virus infection is important since there is no effective treatment for the disease. The infection can be prevented by avoiding exposure to bats in endemic areas and sick pigs. Drinking of raw palm sap (palm toddy) contaminated by bat excrete,[19] eating of fruits partially consumed by bats and using water from wells infested by bats[20] should be avoided. Bats are known to drink toddy that is collected in open containers, and occasionally urinate in it, which makes it contaminated with the virus.[19] Switching to closed top containers prevents transmission via this route. Surveillance and awareness are important for preventing future outbreaks. The association of this disease within reproductive cycle of bats is not well studied. Standard infection control practices should be enforced to prevent nosocomial infections. A subunit vaccine using the Hendra G protein was found to produce cross-protective antibodies against henipavirus and nipavirus has been used in monkeys to protect against Hendra virus, although its potential for use in humans has not been studied.[21]

Treatment

Currently there is no specific treatment for Nipah virus infection as of 2020.[22] The mainstay of treatment is supportive care.[23][22] Standard infection control practices and proper barrier nursing techniques are recommended to avoid the spread of the infection from person to person.[23] All suspected cases of Nipah virus infection should be isolated.[24] While tentative evidence supports the use of ribavirin, it has not yet been studied in people with the disease.[23] Specific antibodies have also been studied in an animal model with potential benefit.[23] Acyclovir and favipiravir has also been tried,[22] as has remdesivir.[25]

Outbreaks

Nipah virus outbreaks have been reported in Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh and India. The highest mortality due to Nipah virus infection has occurred in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, the outbreaks are typically seen in winter season.[26] Nipah virus first appeared in Malaysia in 1998 in peninsular Malaysia in pigs and pig farmers. By mid-1999, more than 265 human cases of encephalitis, including 105 deaths, had been reported in Malaysia, and 11 cases of either encephalitis or respiratory illness with one fatality were reported in Singapore.[27] In 2001, Nipah virus was reported from Meherpur District, Bangladesh[28][29] and Siliguri, India.[28] The outbreak again appeared in 2003, 2004 and 2005 in Naogaon District, Manikganj District, Rajbari District, Faridpur District and Tangail District.[29] In Bangladesh, there were also outbreaks in subsequent years.[30][8]

- 1998 - 1999 September 1998 - May 1999, in the states of Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Selangor in Malaysia. A total of 265 cases of acute encephalitis with 105 deaths caused by the virus were reported in the three states throughout the outbreak.[31] The Malaysian health authorities at the first thought Japanese encephalitis (JE) was the cause of infection which hampered the deployment of effective measures to prevent the spread.[32]

- 2001 January 31–23 February, Siliguri, India: 66 cases with a 74% mortality rate.[33] 75% of patients were either hospital staff or had visited one of the other patients in hospital, indicating person-to-person transmission.

- 2001 April – May, Meherpur District, Bangladesh: 13 cases with nine fatalities (69% mortality).[34]

- 2003 January, Naogaon District, Bangladesh: 12 cases with eight fatalities (67% mortality).[34]

- 2004 January – February, Manikganj and Rajbari districts, Bangladesh: 42 cases with 14 fatalities (33% mortality).

- 2004 19 February – 16 April, Faridpur District, Bangladesh: 36 cases with 27 fatalities (75% mortality). 92% of cases involved close contact with at least one other person infected with Nipah virus. Two cases involved a single short exposure to an ill patient, including a rickshaw driver who transported a patient to hospital. In addition, at least six cases involved acute respiratory distress syndrome, which has not been reported previously for Nipah virus illness in humans.

- 2005 January, Tangail District, Bangladesh: 12 cases with 11 fatalities (92% mortality). The virus was probably contracted from drinking date palm juice contaminated by fruit bat droppings or saliva.[35]

- 2007 February – May, Nadia District, India: up to 50 suspected cases with 3–5 fatalities. The outbreak site borders the Bangladesh district of Kushtia where eight cases of Nipah virus encephalitis with five fatalities occurred during March and April 2007. This was preceded by an outbreak in Thakurgaon during January and February affecting seven people with three deaths.[36] All three outbreaks showed evidence of person-to-person transmission.

- 2008 February – March, Manikganj and Rajbari districts, Bangladesh: Nine cases with eight fatalities.[37]

- 2010 January, Bhanga subdistrict, Faridpur, Bangladesh: Eight cases with seven fatalities. During March, one physician of Faridpur Medical College Hospital caring for confirmed Nipah cases died[38]

- 2011 February: An outbreak of Nipah Virus occurred at Hatibandha, Lalmonirhat, Bangladesh. The deaths of 21 schoolchildren due to Nipah virus infection were recorded on 4 February 2011. IEDCR confirmed the infection was due to this virus.[39] Local schools were closed for one week to prevent the spread of the virus. People were also requested to avoid consumption of uncooked fruits and fruit products. Such foods, contaminated with urine or saliva from infected fruit bats, were the most likely source of this outbreak.[40]

- 2018 May: Deaths of seventeen[41] people in Perambra near Calicut, Kerala, India were confirmed to be due to the virus. Treatment using antivirals such as Ribavirin was initiated.[42][43]

- 2019 June: A 23-year-old student was admitted into hospital with Nipah virus infection at Kochi in Kerala.[44] Health Minister of Kerala, K. K. Shailaja confirmed that 86 people who have had recent interactions with the patient were under observation. This included two nurses who treated the patient, and had fever and sore throat. The situation was monitored and precautionary steps were taken to control the spread of virus by the Central[45] and State Government.[44] 338 people were kept under observation and 17 of them in isolation by the Health Department of Kerala. After undergoing treatment for 54 days at a private hospital, the 23-year-old student was discharged. On 23 July, the Kerala government declared Ernakulam district to be Nipah-free.[46]

Research

Ribavirin, m102.4 monoclonal antibody and favipiravir are being studied as treatments as of 2019.[47]

Medication

Ribavirin has been studied in a small number of people, however whether or not it is useful is unclear as of 2011, but a few people have returned to their normal life after having been treated with this medicine.[48] In vitro studies and animal studies have shown conflicting results in the efficacy of ribavirin against NiV and Hendra, with some studies showing effective inhibition of viral replication in cell lines[49][50] whereas some studies in animal models showed that ribavirin treatment only delayed but did not prevent death after NiV or Hendra virus infection.[51][52]

The anti-malarial drug chloroquine was shown to block the critical functions needed for maturation of Nipah virus, although no clinical benefit has yet been observed.[53]

Immunization

Passive immunization using a human monoclonal antibody - m102.4 that targets the ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3 receptor binding domain of the henipavirus Nipah G glycoprotein has been evaluated in the ferret model as post-exposure prophylaxis.[6][13] m102.4, has been used in people on a compassionate use basis in Australia and was in pre-clinical development in 2013.[6]

Popular culture

A Malayalam movie Virus was released in 2019, based on the 2018 Kerala (India) outbreak of Nipah virus.[54][55]

The fictional MEV-1 virus featured in the 2011 film Contagion was based on a combination of the Nipah virus and the Measles virus[56]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Signs and Symptoms Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 "WHO Nipah Virus (NiV) Infection". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Transmission Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Diagnosis Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Prevention Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Broder CC, Xu K, Nikolov DB, Zhu Z, Dimitrov DS, Middleton D, et al. (October 2013). "A treatment for and vaccine against the deadly Hendra and Nipah viruses". Antiviral Research. 100 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.012. PMC 4418552. PMID 23838047.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Morbidity and mortality due to Nipah or Nipah-like virus encephalitis in WHO South-East Asia Region, 2001-2018" (PDF). SEAR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

112 cases since Oct 2013

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Nipah virus outbreaks in the WHO South-East Asia Region". South-East Asia Regional Office. WHO. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Nipah virus". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ↑ CNN, Manveena Suri (22 May 2018). "10 confirmed dead from Nipah virus outbreak in India". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ↑ "Nipah virus outbreak: Death toll rises to 14 in Kerala, two more cases identified". Hindustan Times. 27 May 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ↑ "After the outbreak". Frontline. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 "Nipah Virus (NiV) CDC". www.cdc.gov. CDC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Luby SP, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Ahmed BN, Banu S, Khan SU, et al. (August 2009). "Recurrent zoonotic transmission of Nipah virus into humans, Bangladesh, 2001-2007". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (8): 1229–35. doi:10.3201/eid1508.081237. PMC 2815955. PMID 19751584. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Nikolay B, Salje H, Hossain MJ, Khan AK, Sazzad HM, Rahman M, et al. (May 2019). "Transmission of Nipah Virus - 14 Years of Investigations in Bangladesh". The New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (19): 1804–1814. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1805376. PMC 6547369. PMID 31067370.

- ↑ Luby, Stephen P.; Gurley, Emily S.; Hossain, M. Jahangir (2012). Transmission of Human Infection with Nipah Virus. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Balan, Sarita (21 May 2018). "6 Nipah virus deaths in Kerala: Bat-infested house well of first victims sealed". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ "Nipah Virus Infection symptoms, causes, treatment, medicine, prevention, diagnosis". myUpchar. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Islam MS, Sazzad HM, Satter SM, Sultana S, Hossain MJ, Hasan M, et al. (April 2016). "Nipah Virus Transmission from Bats to Humans Associated with Drinking Traditional Liquor Made from Date Palm Sap, Bangladesh, 2011-2014". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (4): 664–70. doi:10.3201/eid2204.151747. PMC 4806957. PMID 26981928.

- ↑ Balan, Sarita (21 May 2018). "6 Nipah virus deaths in Kerala: Bat-infested house well of first victims sealed". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Bossart KN, Rockx B, Feldmann F, Brining D, Scott D, LaCasse R, et al. (August 2012). "A Hendra virus G glycoprotein subunit vaccine protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus challenge". Science Translational Medicine. 4 (146): 146ra107. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004241. PMC 3516289. PMID 22875827.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Sharma, V; Kaushik, S; Kumar, R; Yadav, JP; Kaushik, S (January 2019). "Emerging trends of Nipah virus: A review". Reviews in Medical Virology. 29 (1): e2010. doi:10.1002/rmv.2010. PMID 30251294.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "Treatment | Nipah Virus (NiV) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "Nipah yet to be confirmed, 86 under observation: Shailaja". OnManorama. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ↑ Lo, Michael K.; Feldmann, Friederike; Gary, Joy M.; Jordan, Robert; Bannister, Roy; Cronin, Jacqueline; Patel, Nishi R.; Klena, John D.; Nichol, Stuart T.; Cihlar, Tomas; Zaki, Sherif R. (29 May 2019). "Remdesivir (GS-5734) protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus challenge". Science Translational Medicine. 11 (494): eaau9242. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9242. ISSN 1946-6234. PMC 6732787. PMID 31142680.

- ↑ Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, et al. (February 2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- ↑ Eaton BT, Broder CC, Middleton D, Wang LF (January 2006). "Hendra and Nipah viruses: different and dangerous". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 4 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1323. PMC 7097447. PMID 16357858. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, et al. (February 2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, Ali MM, Ksiazek TG, Kuzmin I, et al. (December 2004). "Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (12): 2082–7. doi:10.3201/eid1012.040701. PMC 3323384. PMID 15663842.

- ↑ "Arguments in Bahodderhat murder case begin". The Daily Star. 18 March 2008. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Looi, Lai-Meng; Chua, Kaw-Bing (2007). "Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia" (PDF). The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. Department of Pathology, University of Malaya and National Public Health Laboratory of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. 29 (2): 63–67. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019.

- ↑ Looi, Lai-Meng; Chua, Kaw-Bing (2007). "Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia" (PDF). The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. Department of Pathology, University of Malaya and National Public Health Laboratory of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. 29 (2): 63–67. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019.

- ↑ Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L (2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD (2004). "Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (12): 2082–7. doi:10.3201/eid1012.040701. PMC 3323384. PMID 15663842.

- ↑ ICDDR,B (2005). "Nipah virus outbreak from date palm juice". Health and Science Bulletin. 3 (4): 1–5. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006.

- ↑ ICDDR,B (2007). "Person-to-person transmission of Nipah infection in Bangladesh". Health and Science Bulletin. 5 (4): 1–6. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ↑ ICDDR,B (2008). "Outbreaks of Nipah virus in Rajbari and Manikgonj". Health and Science Bulletin. 6 (1): 12–3. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ↑ ICDDR,B (2010). "Nipah outbreak in Faridpur District, Bangladesh, 2010". Health and Science Bulletin. 8 (2): 6–11. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- ↑ "Arguments in Bahodderhat murder case begin". The Daily Star. 18 March 2008. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ তাহেরকে ফাঁসি দেওয়ার সিদ্ধান্ত নেন জিয়া. prothom-alo.com. 4 February 2011

- ↑ "Nipah virus outbreak: Death toll rises to 14 in Kerala, two more cases confirmed". indianexpress.com. 27 May 2018. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ↑ "Kozhikode on high alert as three deaths attributed to Nipah virus". The Indian Express. 20 May 2018. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ "Deadly Nipah virus claims victims in India". BBC News. 21 May 2018. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Kerala Govt Confirms Nipah Virus, 86 Under Observation". New Delhi. 4 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ↑ Sharma, Neetu Chandra (4 June 2019). "Centre gears up to contain re-emergence of Nipah virus in Kerala". Mint. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ KochiJuly 23, Press Trust of India; July 23, 2019UPDATED; Ist, 2019 19:32. "Ernakulam district declared Nipah virus free, says Kerala health minister". India Today. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Banerjee, S; Gupta, N; Kodan, P; Mittal, A; Ray, Y; Nischal, N; Soneja, M; Biswas, A; Wig, N (February 2019). "Nipah virus disease: A rare and intractable disease". Intractable & Rare Diseases Research. 8 (1): 1–8. doi:10.5582/irdr.2018.01130. PMC 6409114. PMID 30881850.

- ↑ Vigant F, Lee B (June 2011). "Hendra and nipah infection: pathology, models and potential therapies". Infectious Disorders Drug Targets. 11 (3): 315–36. doi:10.2174/187152611795768097. PMC 3253017. PMID 21488828.

- ↑ Wright PJ, Crameri G, Eaton BT (March 2005). "RNA synthesis during infection by Hendra virus: an examination by quantitative real-time PCR of RNA accumulation, the effect of ribavirin and the attenuation of transcription". Archives of Virology. 150 (3): 521–32. doi:10.1007/s00705-004-0417-5. PMID 15526144. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ Aljofan M, Saubern S, Meyer AG, Marsh G, Meers J, Mungall BA (June 2009). "Characteristics of Nipah virus and Hendra virus replication in different cell lines and their suitability for antiviral screening". Virus Research. 142 (1–2): 92–9. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2009.01.014. PMC 2744099. PMID 19428741.

- ↑ Georges-Courbot MC, Contamin H, Faure C, Loth P, Baize S, Leyssen P, et al. (May 2006). "Poly(I)-poly(C12U) but not ribavirin prevents death in a hamster model of Nipah virus infection". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 50 (5): 1768–72. doi:10.1128/AAC.50.5.1768-1772.2006. PMC 1472238. PMID 16641448.

- ↑ Freiberg AN, Worthy MN, Lee B, Holbrook MR (March 2010). "Combined chloroquine and ribavirin treatment does not prevent death in a hamster model of Nipah and Hendra virus infection". The Journal of General Virology. 91 (Pt 3): 765–72. doi:10.1099/vir.0.017269-0. PMC 2888097. PMID 19889926.

- ↑ Broder CC, Xu K, Nikolov DB, Zhu Z, Dimitrov DS, Middleton D, et al. (October 2013). "A treatment for and vaccine against the deadly Hendra and Nipah viruses". Antiviral Research. 100 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.012. PMC 4418552. PMID 23838047.

- ↑ Virus, archived from the original on 8 September 2019, retrieved 1 September 2019

- ↑ Virus Movie Review {3.5/5}: A well-crafted multi-starrer, fictional documentation on the Nipah virus attack, retrieved 1 September 2019

- ↑ "Nipah virus inspired "Contagion." We're testing a vaccine". www.path.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

![How the Nipah virus spreads[18]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/How_the_Nipah_Virus_spreads.png/516px-How_the_Nipah_Virus_spreads.png)