Neurocysticercosis

| Neurocysticercosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Magnetic resonance image of neurocysticercosis demonstrating multiple cysticerci within the brain. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, neurology |

| Symptoms | Seizures, headaches, increased intracranial pressure, other neurological problems; many have no symptoms[1] |

| Complications | Epilepsy, dementia[2] |

| Types | Parenchymal, extraparenchymal[1] |

| Causes | Eating Taenia solium eggs |

| Risk factors | Rural areas that lack proper sanitation[1] |

| Treatment | Antiparasitic medication, corticosteroids surgery[3] |

| Medication | Albendazole, praziquantel, dexamethasone[3] |

| Frequency | 2.5 to 8.3 million people[1] |

Neurocysticercosis is a form of the parasitic disease, cysticercosis, in which cysts develop in the nervous system.[1] Symptoms may include seizures, headaches, increased intracranial pressure, and other neurological problems; though many have few or no symptoms.[1] It is a frequent cause of epilepsy worldwide, representing about a third of cases were the infection is common.[1]

It is caused by eating eggs, found in the stool of humans with the tapeworm Taenia solium.[1] Risk factors include living with someone who has the tapeworm.[2] People get infected by the tapeworm from eating undercooked infected pig.[1] Diagnosis is by medical imaging, either MRI or CT scan, supported by blood tests.[1][2] It can appear similar to nearly all other neurological problems.[2]

Antiparasitic medication (albendazole or praziquantel) together with corticosteroids may be recommended in people who have live cysts within brain tissue that result in symptoms.[1][3] Antiseizure medications are also often used.[1] Surgery may be required in certain cases.[1] Prevention include vaccinating pigs, preventing their exposure to human feces, and treating humans with taeniasis.[1]

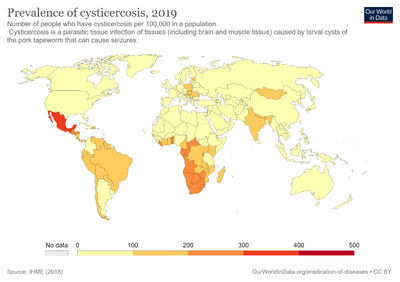

Neurocysticercosis is estimated to affect 2.5 to 8.3 million people.[1] It occurs most commonly in Latin America, South East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.[1] It is particularly common in rural areas that lack proper sanitation.[1] The risk of death is higher in extraparenchymal compared to parenchymal disease.[2] It is a World Health Organization neglected tropical disease.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may include seizures, headaches, increased intracranial pressure, and other neurological problems; though many have few or no symptoms.[1]

Pathophysiology

Neurocysticercosis most commonly involves the cerebral cortex followed by the cerebellum. The pituitary gland is very rarely involved in neurocysticercosis. The cysts may rarely coalesce and form a tree-like pattern which is known as racemose neurocysticercosis, which when involving the pituitary gland may result in multiple pituitary hormone deficiency.[4]

Diagnosis

Neurocysticerosis is diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) scan or MRI.[5] Diagnosis may be supported by finding certain antibodies in the blood, specifically using lentil lectin purified glycoprotein antigen (LLGP).[2] Though this blood test may be negative in people with only one cyst or those with calcified cysts.[2] Additionally the test may be positive in those with prior infection or cysts elsewhere in the body.[2] Testing the CSF via ELISA may be helpful in certain cases.[2]

Treatment

Treatment of neurocysticercosis includes antiseizure medication. Certain cases may be treated with the antiparasitic medication, praziquantel (PZQ) or albendazole.[3] Steroid therapy, generally dexamethasone or prednisone, is used to minimize the inflammatory reaction to dying cysticerci during this treatment.[3] Surgical removal of brain cysts may be necessary, e.g. in cases of large parenchymal cysts, intraventricular cysts or hydrocephalus.[6][7]

Antiparasitic medication

Certain cases may be treated with antiparasitic medication; however, a number of contraindication to their use exist.[3] This includes those with dozens of colloidal cysts and those with intracranial hypertension.[3] Repeat imaging is generally carried out six month following treatment.[3]

For those with cysts within the brain tissue doses of albendazole are 7.5 mg/kg twice per day and doses of praziquantel are 16.7 mg/kg three times per day.[3] They are used for 10 to 14 days.[3] Both may be used together.[3]

For those with cysts outside the brain tissue doses of albendazole are 15 mg/kg twice per day.[3] Treatment may be repeated six month later or a longer course of treatment may be used.[3]

Albendazole has been shown to reduce seizure recurrence in those with a single non-viable intraparenchymal cyst.[8] For those with only calcified areas antiparasitic medication is not needed.[3]

Seizures

For seizures, antiepileptic drugs (AED) are used similar to in epilepsy.[3] These are used for at least 6 months to two years.[3] Further trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of AEDs for seizure prevention in people with symptoms other than seizures and the duration of AED treatment in these cases.[9]

Epidemiology

Neurocysticercosis is associated with poor sanitation and is common in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Asia.[10][11][12] It commonly affects the poor and homeless, particularly those without access or in the habit of inadequate hand-washing and in the habit of eating with their hands.[citation needed]

Society and culture

Cysticercosis has been classified as a "neglected tropical disease".[13]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 WHO guidelines on management of taenia solium neurocysticercosis. Geneva. 2021. ISBN 978-92-4003223-1. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Garcia, HH; Nash, TE; Del Brutto, OH (December 2014). "Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis". The Lancet. Neurology. 13 (12): 1202–15. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70094-8. PMID 25453460. Archived from the original on 2023-02-16. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Considerations for the use of anthelminthic therapy for the treatment of neurocysticercosis. World Health Organization. 28 March 2023. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ↑ Dutta, Deep; Kumar, Mano; Ghosh, Sujoy; Mukhopadhyay, Satinath; Chowdhury, Subhankar (2013). "Pituitary hormone deficiency due to racemose neurocysticercosis". The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 1 (2): e13. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70026-3. PMID 24622323.

- ↑ "WHO | 10 facts about neurocysticercosis". WHO. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ↑ Rajshekhar (4 January 2010). "Surgical management of neurocysticercosis". International Journal of Surgery. 8 (2): 100–104. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.12.006. PMID 20045747.

- ↑ Murray, P.; Rosenthal, K.; Pfaller, M. (2013). "Chapter 85 — Cestodes". Medical Microbiology (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA, USA: Elsevier Saunders. p. 809. ISBN 978-0-323-08692-9.

- ↑ Monk, Edward J. M.; Abba, Katharine; Ranganathan, Lakshmi N. (2021-06-01). "Anthelmintics for people with neurocysticercosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (6): CD000215. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000215.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8167835. PMID 34060667.

- ↑ Frackowiak, Marta; Sharma, Monika; Singh, Tejinder; Mathew, Amrith; Michael, Benedict D. (2019-10-14). "Antiepileptic drugs for seizure control in people with neurocysticercosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD009027. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009027.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6790915. PMID 31608991.

- ↑ Flisser, Ana; Sarti, Elsa; Lightowlers, Marshall; Schantz, Peter (2003-06-01). "Neurocysticercosis: regional status, epidemiology, impact and control measures in the Americas". Acta Tropica. International Action Planning Workshop on Taenia Solium Cysticercosis/Taeniosis with Special Focus on Eastern and Southern Africa. 87 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(03)00054-8. PMID 12781377.

- ↑ Mwanjali, Gloria; Kihamia, Charles; Kakoko, Deodatus Vitalis Conatus; Lekule, Faustin; Ngowi, Helena; Johansen, Maria Vang; Thamsborg, Stig Milan; Iii, Arve Lee Willingham (2013-03-14). "Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Human Taenia Solium Infections in Mbozi District, Mbeya Region, Tanzania". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (3): e2102. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002102. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 3597471. PMID 23516650.

- ↑ Schantz, Peter M.; Moore, Anne C.; Muñoz, José L.; Hartman, Barry J.; Schaefer, John A.; Aron, Alan M.; Persaud, Deborah; Sarti, Elsa; Wilson, Marianna (1992-09-03). "Neurocysticercosis in an Orthodox Jewish Community in New York City". New England Journal of Medicine. 327 (10): 692–695. doi:10.1056/NEJM199209033271004. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 1495521.

- ↑ Hotez, Peter J. (2014). "Neglected Parasitic Infections and Poverty in the United States". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (9): e3012. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003012. PMC 4154650. PMID 25188455.