Nephronophthisis

| Nephronophthisis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Medullary cystic kidney disease (historical),[1] familial juvenile nephronophthisis[1] | |

| |

| Nephronophthisis has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

| Symptoms | Infantile: Oligohydramnios sequence[2] Juvenile&adult: Increased urination, delayed milestone, low red blood cells[2] |

| Complications | Kidney failure[2] |

| Types | Infantile, juvenile, adolescent[2] |

| Causes | Genetic mutation (autosomal recessive)[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on lab tests, urine tests, and ultrasound[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease[2] |

| Treatment | Management of high blood pressure, electrolyte abnormalities, low red blood cells, dialysis, kidney transplant[2] |

| Frequency | 1 in 50,000 to 1,000,000[2] |

Nephronophthisis (NPHP) is a genetic disorder of the kidneys.[3] There are three types infantile, juvenile, and adolescent.[2] The infantile form begins before birth and presents with oligohydramnios sequence.[2] The juvenile and adolescent forms presents in childhood with increased urination, delayed milestone, and low red blood cells.[2] Kidney failure occurs before the age of 30.[2]

It is due to mutations in the NPHP genes.[1] It is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion.[1] Up to 20% of cases may present as part of another syndrome such as Joubert or Bardet-Biedl.[2] It is classified as a ciliopathy.[2] Diagnosis is based on on lab tests, urine tests, and ultrasound of the kidneys.[2]

Treatment may include managing high blood pressure, electrolyte abnormalities, and low red blood cells.[2] Growth hormone may be useful in certain cases.[2] Kidney failure may be treated with dialysis or kidney transplant.[2]

It effects between 1 in 50,000 newborns in Canada and Finland to 1 in a million in the United States.[2] It is the most common genetic cause of kidney failure before the age of 30.[1] Nephronophthisis was first described by Smith and Graham in 1945.[1] The word itself means "wasting of the nephrons".[2]

Signs and symptoms

Infantile, juvenile, and adolescent forms of nephronophthisis have been identified. Although the range of characterizations is broad, people affected by nephronophthisis typically present with polyuria (production of a large volume of urine), polydipsia (excessive liquid intake), and after several months to years, end-stage kidney disease, a condition necessitating either dialysis or a kidney transplant in order to survive.[4] Some individuals that suffer from nephronophthisis also have so-called "extra-renal symptoms" which can include tapetoretinal degeneration, liver problems, ocularmotor apraxia, and cone-shaped epiphysis (Saldino-Mainzer syndrome).[5][6]

Cause

Nephronophthisis is characterized by fibrosis and the formation of cysts at the cortico-medullary junction, it is an autosomal recessive disorder which eventually leads to kidney failure.[7]

Pathophysiology

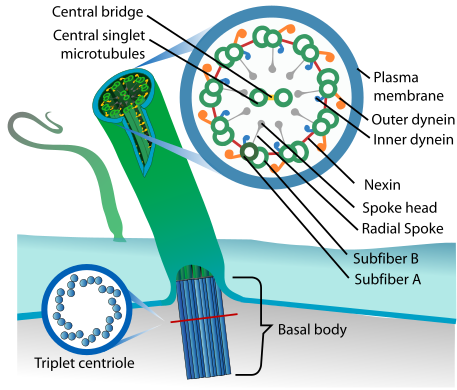

Mechanism of nephronophthisis indicates that all proteins mutated in cystic kidney diseases express themselves in primary cilia. NPHP gene mutations cause defects in signaling resulting in flaws of planar cell polarity. The ciliary theory indicates that multiple organs are involved in NPHP (retinal degeneration, cerebellar hypoplasia, liver fibrosis, and intellectual disability).[8]

-

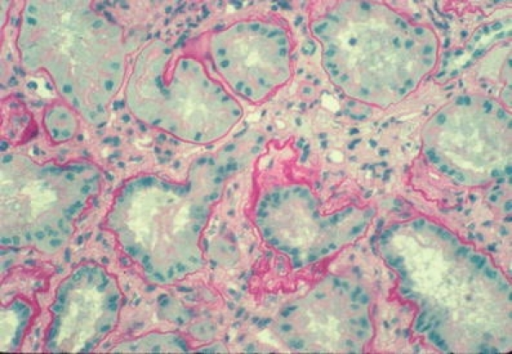

Histology of nephronophthisis, cross-section of kidney showing diffuse interstitial fibrosis

-

Ciliopathy (eukaryotic cilium diagram)

Related genetic disorders

Nephronophthisis is a ciliopathy. Other known ciliopathies include primary ciliary dyskinesia, Bardet–Biedl syndrome, polycystic kidney and liver disease, Alström syndrome, Meckel–Gruber syndrome and some forms of retinal degeneration.[9]

NPHP2 is infantile type of nephropthisis and sometimes associated with situs inversus this can be explained by its relation with inversin gene. NPHP1, NPHP3, NPHP4, NPHP5, and NPHP6 are sometimes seen with retinitis pigmentosa, this particular association has a name, Senior-Loken syndrome.[10]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of nephronophthisis can be obtained via a kidney ultrasound, family history and clinical history of the affected individual according to Stockman, et al.[11]

Types

Management

The management of this condition can be done via-improvement of any electrolyte imbalance, as well as, high blood pressure and low red blood cell counts (anemia) treatment as the individual's condition warrants.[11]

Epidemiology

Nephronophthisis occurs equally in both sexes and has an estimate 9 in about 8 million rate in individuals. Nephronophthisis is the leading monogenic cause of end-stage kidney disease.[12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Wolf, MT; Hildebrandt, F (February 2011). "Nephronophthisis". Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 26 (2): 181–94. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1585-z. PMID 20652329.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Stokman, M; Lilien, M; Knoers, N; Adam, MP; Ardinger, HH; Pagon, RA; Wallace, SE; Bean, LJH; Mirzaa, G; Amemiya, A (2016). "Nephronophthisis". GeneReviews. PMID 27336129.

- ↑ "Nephronophthisis: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ Hildebrandt, Friedhelm; Zhou, Weibin (2007). "Nephronophthisis-Associated Ciliopathies". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 18 (6): 1855–71. doi:10.1681/ASN.2006121344. PMID 17513324.

- ↑ Kanwal, Kher (2007). Clinical Pediatric Nephrology, Second Edition (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-84184-447-3. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ↑ Medullary Cystic Disease~clinical at eMedicine

- ↑ Salomon, Rémi; Saunier, Sophie; Niaudet, Patrick (2009). "Nephronophthisis". Pediatric Nephrology. 24 (12): 2333–44. doi:10.1007/s00467-008-0840-z. PMC 2770134. PMID 18607645.

- ↑ Hildebrandt, Friedhelm; Attanasio, Massimo; Otto, Edgar (2009). "Nephronophthisis: Disease Mechanisms of a Ciliopathy". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 20 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008050456. PMC 2807379. PMID 19118152.

- ↑ McCormack, Francis X.; Panos, Ralph J.; Trapnell, Bruce C. (2010-03-10). Molecular Basis of Pulmonary Disease: Insights from Rare Lung Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781597453844. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- ↑ Badano, Jose L.; Mitsuma, Norimasa; Beales, Phil L.; Katsanis, Nicholas (2006). "The Ciliopathies: An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 7: 125–48. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. PMID 16722803.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Stokman, Marijn; Lilien, Marc; Knoers, Nine (1 January 1993). "Nephronophthisis". GeneReviews. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2016.update 2016

- ↑ Hildebrandt, Friedhelm (2009). "Nephronophthisis". In Lifton, Richard P.; Somlo, Stefan; Giebisch, Gerhard H.; et al. (eds.). Genetic Diseases of the Kidney. Academic Press. pp. 425–46. ISBN 978-0-08-092427-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Simms, Roslyn J.; Hynes, Ann Marie; Eley, Lorraine; Sayer, John A. (2011). "Nephronophthisis: A Genetically Diverse Ciliopathy". International Journal of Nephrology. 2011: 1–10. doi:10.4061/2011/527137. PMC 3108105. PMID 21660307.

- Hildebrandt, Friedhelm; Attanasio, Massimo; Otto, Edgar (2009-01-01). "Nephronophthisis: Disease Mechanisms of a Ciliopathy". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 20 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008050456. ISSN 1046-6673. PMC 2807379. PMID 19118152.

External links

| Classification |

|---|