Mycetoma

| Mycetoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Madura foot, maduramycosis[1] | |

| |

| Mycetoma foot | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Triad: painless firm skin lump, multiple weeping sinuses, grainy discharge[1] |

| Usual onset | Slowly progressive[2] |

| Types |

|

| Diagnostic method | Ultrasound, fine needle aspiration[2] |

Mycetoma is a long-term infection deep in the skin, resulting in a triad of symptoms; painless firm skin lumps, weeping sinuses, and a discharge that contains grains.[1] 80% occur in feet.[2]

It is caused by either bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma).[2] Most eumycetoma is caused by M. mycetomatis, whereas most actinomycetoma is caused by Nocardia brasiliensis, Streptomyces somaliensis, Actinomadura madurae and Actinomadura pelletieri.[2] People who develop mycetoma likely have a weakened immune system.[2] It can take between 3 months to 50 years from time of infection to first seeking healthcare advice.[2]

Diagnosis requires ultrasound and fine needle aspiration.[2]

While most cases of mycetoma occur in Sudan, Venezuela, Mexico, and India, its true prevalence and incidence are not well-known.[3][4] It appears most frequently in people living in rural areas, particularly farmers and shepherds; men between 20 and 40 years who tend to be the breadwinners.[2] It has been described in ancient Sanskrit scriptures as "anthill foot", and was reported by John Gill in 1842 in Madurai, India..[1] The disease is listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neglected tropical disease.[5]

Symptoms and signs

Mycetoma's presentation is that of a small mass under the skin, usually in the lower extremities (foot)[6]

-

Mycetoma

-

Mycetoma foot

-

Actinomycetoma

Risk factor

Frequent exposure to penetrating wounds by thorns or splinters is a risk factor.[7] This risk can be reduced by disinfecting wounds and wearing shoes.[8]

Pathogenesis

Mycetoma is caused by common saprotrophs found in the soil and on thorny shrubs in semi-desert climates.[8] The most common causative agents are:[2]

- Madurella mycetomatis (fungus)[2]

- Nocardia brasiliensis (bacteria)[2]

- Actinomadure madura (bacteria)[2]

- Streptomyces somaliensis (bacteria)[2]

- Actinomadura pelletieri (bacteria)[2]

Infection is caused as a result of localized skin trauma, such as stepping on a needle or wood splinter, or through a pre-existing wound.[8]

The first visible symptom of mycetoma is a typically painless swelling beneath the skin; over several years, this will grow to a nodule (lump).[7] Affected people will experience massive swelling and hardening of the area, in addition to skin rupture and the formation of sinus tracts that discharge pus and grains filled with organisms.[7] In many instances, the underlying bone is affected.[9][8] Some people with mycetoma will not experience pain or discomfort, while others will report itching and/or pain.[7]

-

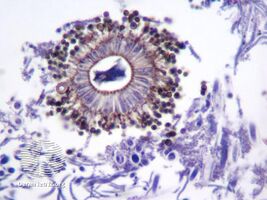

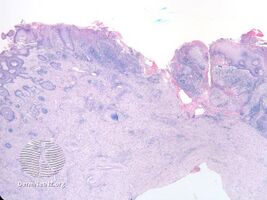

pathology-Mycetoma

-

pathology-Mycetoma

Diagnosis

There are currently no rapid diagnostic tools for mycetoma.[4] Mycetoma is diagnosed through microscopic examination of the grains in the nodule and by analysis of cultures.[8] Since the bacterial form and the fungal form of mycetoma infection of the foot share similar clinical and radiological features, diagnosis can be a challenge.[3] Magnetic resonance imaging is a very valuable diagnostic tool. However, its results should be closely correlated with the clinical, laboratory and pathological findings.[9][10]

Treatment

While treatment will vary depending on the cause of the condition, it may include antibiotics or antifungal medication.[7] Actinomycetoma, the bacterial form, can be cured with antibiotics.[3] Eumycetoma, the fungal form, is treated with antifungals.[10] Surgery in the form of bone resection may be necessary in late presenting cases or to enhance the effects of medical treatment.[9] In the more extensive cases amputation is another surgical treatment option.[11][8] For both forms, extended treatment is necessary.[3]

Epidemiology

Mycetoma is endemic in some regions of the tropics and subtropics.[2] India, Sudan and Mexico are most affected.[2]

History

It has been described in ancient Sanskrit scriptures as "anthill foot", and was reported by John Gill in 1842 in India..[1]

Social and cultural

It generally affects people living in poverty in rural regions.[2] It is listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neglected tropical disease.[4]

Other animals

In cats, mycetoma can be treated with complete surgical removal. Antifungal drugs are rarely effective.[13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Chander, Jagdish (2018). "11. Mycetom". Textbook of Medical Mycology (4th ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd. pp. 203–228. ISBN 978-93-86261-83-0. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Zijlstra, Eduard E.; Sande, Wendy W. J. van de; Welsh, Oliverio; Mahgoub, El Sheikh; Goodfellow, Michael; Fahal, Ahmed H. (1 January 2016). "Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (1): 100–112. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00359-X. ISSN 1473-3099. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Welsh O, Al-Abdely HM, Salinas-Carmona MC, Fahal AH (October 2014). "Mycetoma medical therapy". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (10): e3218. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003218. PMC 4199551. PMID 25330342.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 van de Sande WW, Maghoub El S, Fahal AH, Goodfellow M, Welsh O, Zijlstra E (March 2014). "The mycetoma knowledge gap: identification of research priorities". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (3): e2667. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002667. PMC 3967943. PMID 24675533.

- ↑ Yotsu, Rie R. (14 November 2018). "Integrated Management of Skin NTDs—Lessons Learned from Existing Practice and Field Research". Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 3 (4). doi:10.3390/tropicalmed3040120. ISSN 2414-6366. PMID 30441754. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ↑ "Mycetoma | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 16 September 2020. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Mycetoma". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Mycetoma". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 El-Sobky, TA; Haleem, JF; Samir, S (2015). "Eumycetoma Osteomyelitis of the Calcaneus in a Child: A Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation following Total Calcanectomy". Case Reports in Pathology. 2015: 129020. doi:10.1155/2015/129020. PMC 4592886. PMID 26483983.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Karrakchou, B; Boubnane, I; Senouci, K; Hassam, B (10 January 2020). "Madurella mycetomatis infection of the foot: a case report of a neglected tropical disease in a non-endemic region". BMC Dermatology. 20 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s12895-019-0097-1. PMC 6953183. PMID 31918687.

- ↑ Efared, Boubacar; Tahiri, Layla; Boubacar, Marou Soumana; Atsam-Ebang, Gabrielle; Hammas, Nawal; Hinde, El Fatemi; Chbani, Laila (December 2017). "Mycetoma in a non-endemic area: a diagnostic challenge". BMC Clinical Pathology. 17 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s12907-017-0040-5. ISSN 1472-6890. PMC 5288886. PMID 28167862.

- ↑ Sande, Wendy W. J. van de (7 November 2013). "Global Burden of Human Mycetoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (11): e2550. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002550. ISSN 1935-2735. PMID 24244780. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ↑ Eldredge, Debra M.; Carlson, Delbert G.; Carlson, Liisa D.; Giffin, James M. (2008). Cat Owner's Home Veterinary Handbook. Howell Book House. p. 160.

External links

- DermNet NZ Archived 2016-06-30 at the Wayback Machine: an online resource about skin diseases from the New Zealand Dermatological Society Incorporated.

- Orphanet Archived 2021-03-02 at the Wayback Machine: a reference portal from Europe that provides information on rare diseases and orphan drugs.

- ClinicalTrials.gov Archived 2021-04-04 at the Wayback Machine: a list of clinical trials related to mycetoma.