Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

| Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), post-viral fatigue syndrome (PVFS), chronic fatigue immune dysfunction syndrome (CFIDS), systemic exertion intolerance disease (SEID), others[1]: 20 | |

| |

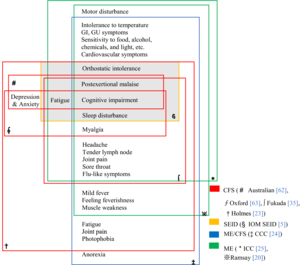

| Chart of the symptoms of ME/CFS according to various definitions | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, rehabilitation medicine, endocrinology, Infectious disease, neurology, immunology, internal medicine, paediatrics, other specialists in ME/CFS[2] |

| Symptoms | Worsening of symptoms with activity, long-term fatigue, others[3] |

| Usual onset | Peaks at 10–19 and 30–39 years old[4] |

| Duration | Long-term[5] |

| Causes | Unknown[3] |

| Risk factors | Female sex, virus and bacterial infections, blood relatives with the illness, major injury, bodily response to psychological stress and others[6][7]: 1–2 |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[3] |

| Treatment | Symptomatic[8] |

| Prevalence | About 0.68 to 1% globally[9][10] |

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is a debilitating long-term medical condition. People with ME/CFS experience lengthy flare-ups of the illness following relatively minor physical or mental activity. This is known as post-exertional malaise (PEM) and is the hallmark symptom of the illness. Other core symptoms are a greatly reduced ability to do tasks that were previously routine, severe fatigue, and sleep disturbances. The baseline fatigue in ME/CFS does not improve much with rest.[11][12] Orthostatic intolerance, memory and concentration problems, and chronic pain are common.[12] About a quarter of people with ME/CFS are severely affected and unable to leave their bed or home.[13]: 3

The root cause(s) of the disease are unknown and the mechanisms are not fully understood.[14] ME/CFS often starts after a flu-like infection, for instance after infectious mononucleosis.[15][6] In some people, physical trauma or psychological stress may also act as a trigger.[13]: 10 A genetic component is suspected, as ME/CFS can run in families.[16] ME/CFS is associated with changes in the nervous and immune system, energy metabolism and hormone production.[14][17] Diagnosis is based on symptoms because no confirmed diagnostic test is available.[18]

The course of ME/CFS is hard to predict. The illness may improve, worsen, or fluctuate in severity, but full recovery is rare.[19] Treatment is aimed at relieving symptoms, as no therapies or medications are approved to treat the condition.[8][19] Pacing and activity management can help prevent flare-ups.[8] Counseling may aid in coping with the illness.[8]

About 1% of patients at primary care clinics have ME/CFS. Estimates vary widely because studies have used different definitions.[10][20][9] ME/CFS occurs 1.5 to 2 times as often in women as in men.[10] It most commonly affects adults between 40 and 60 years old,[21] but can occur at other ages, including childhood.[22] ME/CFS significantly reduces health, happiness and productivity, and can cause loneliness and alienation.[23]

People with ME/CFS often face stigma in healthcare settings, and doctors may have trouble managing an illness that lacks a clear cause or treatment.[1]: 30 [24] Historical research funding for ME/CFS has been far below that of comparable diseases.[25] There is controversy over many aspects of the condition, including the name, cause and potential treatments.[26]

Classification

ME/CFS has been classified as neurological disease by the World Health Organization (WHO) since 1969, initially under the name benign myalgic encephalomyelitis.[27] Even though the cause of the illness is unknown, symptoms point to a central role of the nervous system.[28] Alternatively, based on abnormalities of immune cells, it has been classified as a neuroimmune condition.[29]

In the WHO's most recent classification, ICD-11, both chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis are listed under the term post-viral fatigue syndrome. They are classified as other disorders of the nervous system.[30] In the ICD-10, only (benign) ME was listed, and there was no mention of CFS. Clinicians often used diagnostic codes for fatigue and malaise, or fatigue syndrome for people with CFS.[31]

Signs and symptoms

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends these criteria for diagnosis:[12]

- Greatly lowered ability to do activities that were usual before the illness. This drop in activity level occurs along with fatigue and must last six months or longer.

- Worsening of symptoms after physical or mental activity that would not have caused a problem before the illness. The amount of activity that might aggravate the illness is difficult for a person to predict, and the decline often presents 12 to 48 hours after the activity.[32] The 'relapse', or 'crash', may last days, weeks or longer. This is known as post-exertional malaise (PEM).

- Sleep problems; people may still feel weary after full nights of sleep, or may struggle to stay awake, fall asleep or stay asleep.

Additionally, one of the following symptoms must be present:[12]

- Problems with thinking and memory (cognitive dysfunction, sometimes described as "brain fog")

- While standing or sitting upright; lightheadedness, dizziness, weakness, fainting or vision changes may occur (orthostatic intolerance)

Debilitating fatigue

People with ME/CFS experience a debilitating fatigue, which is made worse by activity, not caused by cognitive, physical, social or emotional overexertion, and minimally alleviated by rest. Particularly in the initial period of illness, this fatigue is described as "flu-like". People with ME/CFS may feel restless, and describe their experience as "wired but tired". When starting an activity, muscle strength may drop rapidly, which can lead to sudden weakness, difficulty with coordination and clumsiness.[19]: 10, 57

Post-exertional malaise

The hallmark feature of ME/CFS is a worsening of symptoms after activity.[13]: 6 This is called post-exertional malaise (PEM) or more accurately post-exertional symptom exacerbation. The term malaise may be considered outdated, as it gives the impression of a "vague discomfort".[33]: 49 PEM involves increased fatigue and functional limitations. It can also include heightened flu-like symptoms, pain, cognitive difficulties, gastrointestinal issues, nausea or sleep disturbances. The crash can lasts hours, days, weeks or months.[13]: 6 Extended durations of PEM are frequently denoted as 'crashes' or flare-ups among individuals with ME/CFS and might foreshadow a prolonged relapse.[33]: 50

All types of activities that require energy can trigger PEM. It can be physical or cognitive, but also social or emotional.[33]: 49 The amount of activity that might aggravate the illness is difficult for a person to predict, and the decline often presents 12 to 48 hours after the activity.[32] At times, PEM starts immediately after the activity.[13]: 6

Sleep problems

There is a wide variety of sleep problems in the ME/CFS population. Sleep is often described as unrefreshing: People wake up exhausted and stiff rather than restored after a night's sleep. This can be caused by a reversed cycle of wakefulness and sleep, shallow sleep or broken sleep. However, even a full night sleep is typically non-restorative. Some people with ME/CFS experience insomnia, hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness) or vivid nightmares.[33]: 50 Sleep apnoea may be present as a co-occurring condition.[34]: 16 However, many diagnostic criteria state that sleep disorders must be excluded before a diagnosis of ME/CFS is confirmed.[13]: 7

Cognitive dysfunction

Cognitive dysfunction is one of the most disabling aspects of CFS due to its negative impact on occupational and social functioning. 50–80% of people with CFS are estimated to have serious problems with cognition.[35] Cognitive symptoms are mainly due to deficits in attention, memory, and reaction time. Measured cognitive abilities are found to be below projected normal values and likely to affect day-to-day activities, causing increases in common mistakes, forgetting scheduled tasks, or having difficulty responding when spoken to.[36]

Simple and complex information-processing speed and functions entailing working memory over long time periods are moderately to extensively impaired. These deficits are generally consistent with the patient's perceptions. Perceptual abilities, motor speed, language, reasoning, and intelligence do not appear to be significantly altered. Patients who report poorer health status tend to also report more severe cognitive trouble, and better physical functioning is associated with less visuoperceptual difficulty and fewer language-processing complaints.[36]: 24

Orthostatic intolerance

People with ME/CFS often experience orthostatic intolerance, symptoms that start or worsen with standing or sitting. Symptoms, which include nausea, lightheadedness and cognitive impairment, often improve again after lying down.[15] Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), an excessive increase in heart rate after standing up, is the most common form of orthostatic intolerance in ME/CFS. Sometimes, POTS can result in fainting.[13]: 7 Orthostatic hypotension, a drop in blood pressure after standing, may also be present.[34]: 17

Other common symptoms

Pain and hyperalgesia (an abnormally increased sensitivity to pain) are common in ME/CFS. The pain is not accompanied by swelling or redness.[34]: 16 The pain can be present in muscles (as myalgia) and joints, in the lymph nodes and as a sore throat. Chronic pain behind the eyes and in the neck and neuropathic pain (related to disorders of the nervous system) is also described.[13]: 8 Headaches and migraines that were not present before the illness can be present as well. However, chronic daily headaches may indicate an alternative diagnosis.[34]: 16 PEM frequently makes pain worse;[13]: 8 Normally, exercise has the opposite effect, making people less sensitive to pain.[37]

Many, but not all people with ME/CFS further report:[12]

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Chills and night sweats

- Allergies and sensitivities to foods, odors, chemicals, lights, or noise

- Shortness of breath

- Irregular heartbeat

Onset

The onset of ME/CFS may be gradual or sudden.[1] When it begins suddenly, it often follows an episode of infectious-like symptoms or a known infection, and between 25% and 80% report an infectious-like onset.[1]: 158 [38] When gradual, the illness may begin over the course of months or years with no apparent trigger.[39] It is also frequent for ME/CFS to begin with multiple triggering events that initially cause minor symptoms and culminate in a final trigger leading to a noticeable onset.[40] Studies disagree as whether sudden or gradual onset is more common.[1]: 158 : 181 ME/CFS may also occur after physical trauma such as a car accident or surgery.[39]

Severity

ME/CFS often causes significant disability, but the degree varies greatly.[39] People with ME/CFS can be divided into four categories of illness severity:[19]: 8 [34]: 10

- People with mild ME/CFS can usually still work and care for themselves, but will need their free time to recover from these activities, rather than engaging in social and leisure activities

- Moderate severity results in a large reduction in activities of daily living (self-care activities, such as feeding and washing oneself). People are usually unable to work and require frequent resting.

- People with severe ME/CFS are homebound and can do only limited activities of daily living.

- In the very severe group, people are mostly bedbound and cannot independently care for themselves.

Roughly a quarter of people with ME/CFS fall in the mild category, half in the moderate or moderate-to-severe category.[41] The final quarter fall in the severe or very severe category.[13]: 3 Severity may change over time, with periods of worsening, improvement or remission sometimes occurring.[39] Persons who feel better for a period may overextend their activities, triggering post-exertional malaise and a worsening of symptoms.[32]

People with severe and very severe ME/CFS experience more or more severe symptoms. They may face severe weakness and may be unable to move at times.[42] They can lose the ability to speak or swallow, or lose the ability to communicate completely due to cognitive issues. They can further experience hypersensitivities to touch, light, sound, and smells, and experience severe pain.[19]: 50 The activities that can trigger post-exertional malaise in these patients are very minor, such as sitting or going to the toilet.[42]

People with ME/CFS have decreased quality of life according to the SF-36 questionnaire, especially in the domains of vitality, physical functioning, general health, physical role, and social functioning. However, their scores in the "role emotional" and mental health domains were not substantially lower than healthy controls.[43] A 2015 study found that people with ME/CFS had lower health-related quality of life than 20 other medical conditions, including multiple sclerosis, kidney failure, and lung cancer.[44]

Cause

The cause of ME/CFS is unknown.[45][15] Both genetic and environmental factors are believed to contribute, but the genetic component is unlikely to be a single gene.[45] Problems with the nervous and immune systems, and energy metabolism, may be factors.[15] ME/CFS is a biological disease, not a psychiatric or psychological condition,[46][45] and is not caused by deconditioning.[45][47]

Because the illness often follows a known or apparent viral illness, various infectious agents have been proposed, but a single cause has not been found.[48][1][45] For instance, ME/CFS may start after mononucleosis, a H1N1 influenza infection, a varicella zoster virus infection (the virus that causes chickenpox), SARS-CoV-1[49]

Risk factors

All ages, ethnic groups, and income levels are susceptible to the illness. The CDC states that while Caucasians may be diagnosed more frequently than other races in America,[50] the illness is at least as prevalent among African Americans and Hispanics.[21] A 2009 meta-analysis found that Asian Americans have a lower risk of CFS than White Americans, while Native Americans have a higher (probably a much higher) risk and African Americans probably have a higher risk. The review acknowledged that studies and data were limited.[51]

More women than men get ME/CFS.[50] A large 2020 meta-analysis estimated that between 1.5 and 2.0 times more cases are women. The review noted that different case definitions and diagnostic methods within datasets yielded a wide range of prevalence rates.[10] The CDC estimates ME/CFS occurs up to four times more often in women than in men.[21] The illness can occur at any age, but has the highest prevalence in people aged 40 to 60.[21] ME/CFS is less prevalent among children and adolescents than among adults.[22]

People with affected relatives appear to be more likely to get ME/CFS, implying the existence of genetic risk factors.[16] People with a family history of neurological or autoimmune diseases are also at increased risk.[40] Results of genetic studies have been largely contradictory or unreplicated. One study found an association with mildly deleterious mitochondrial DNA variants, and another found an association with certain variants of human leukocyte antigen genes.[16]

Viral and other infections

Viral infections have long been suspected to cause ME/CFS, based on the observation ME/CFS sometimes occurs in outbreaks and is connected to autoimmune diseases.[52] Post-viral fatigue syndrome (PVFS) describes a type of ME/CFS that occurs following a viral infection.[38]

Different types of viral infection have been implicated in ME/CFS, including airway infections, bronchitis, gastroenteritis, or an acute "flu-like illness".[13]: 226 A meta-analysis of different viral infections identified the borna disease virus as having the highest odds of causing ME/CFS. Six other viral infections were also identified with a weaker link to ME/CFS. The analysis did not include COVID-19.[52] Between 15% to 50% of people with long COVID also meet the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS.[13]: 228

Reactivation of latent viruses have also been hypothesized to drive symptoms, in particular Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). EBV is present in about 90% of people, usually in a latent state.[53] EBV antibody activity is often higher in people with ME/CFS, indicating reactivation.[54] Of people who get infection mononucleosis, which is triggered by EBV, around 8% to 15% develop ME/CFS, depending on criteria.[13]: 226

A systematic review found that fatigue severity was the main predictor of prognosis in CFS, and did not identify psychological factors linked to prognosis.[55] Another review found that risk factors for developing post-viral fatigue or CFS after mononucleosis, dengue fever, or Q-fever included longer bed-rest during the illness, poorer pre-illness physical fitness, attributing symptoms to physical illness, belief that a long recovery time is needed, as well as pre-infection distress and fatigue.[56] The same review found biological factors such as CD4 and CD8 activation and liver inflammation are predictors of sub-acute fatigue but not CFS.[56]

Pathophysiology

ME/CFS is associated with changes in several areas, including the nervous, immune, and endocrine systems.[14][17] Reported neurological differences include altered brain structure and metabolism, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction.[17] Observed immunological changes include decreased natural killer cell activity, increased cytokines.[14] Endocrine differences, such as modestly low cortisol and HPA axis dysregulation, have been noted as well.[14] Impaired energy production and the possibility of autoimmunity are other areas of interest.[15]

Neurological

A range of structural, biochemical and functional abnormalities is found brain imaging studies in people with ME/CFS.[29][17] A consistent and frequent finding is the recruitment of additional brain areas in cognitive tasks.[28] Other consistent findings, but based on a low number of studies,[28] are regional hypometabolism, reduced serotonin transporters and problems with neurovascular coupling.[28]

Neuroinflammation has been proposed as an underlying mechanism of ME/CFS that could explain a large set of symptoms. A number of studies suggest neuroinflammatory abnormalities in the cortical and limbic regions of the brain in people with ME/CFS. People with ME/CFS for instance have higher brain lactate and choline levels, which point to neuroinflammation. Two small PET studies of microglia, a type of immune cell in the brain, were contradictory however.[57] However, methodological problems and lack of replication mean that further research is necessary, and direct evidence for nervous system inflammation is somewhat limited.[58]

ME/CFS affects sleep. People with ME/CFS experience decreased sleep efficiency, take longer to fall asleep and longer to achieve REM sleep. Changes to non-REM sleep have also been found, together suggesting a role of the autonomic nervous system.[59][60] People with ME/CFS often have an abnormal heart rate response to a tilt table test, in which a patient is moved from a flat to an upright position. This again suggests dysfunction in the autonomic nervous system.[61]

Immunological

People with ME/CFS often have immunological abnormalities. A consistent finding in studies is a decreased activity of natural killer cells, a type of immune cell that targets virus-infected and tumour cells.[6][62] People with ME/CFS have an abnormal response to exercise, including increased production of complement products, increased oxidative stress combined with decreased antioxidant response, and increased interleukin 10, and TLR4, some of which correlates with symptom severity.[63] Increased levels of cytokines have been proposed to account for the decreased ATP production and increased lactate during exercise;[64][65] however, the elevations of cytokine levels are inconsistent in specific cytokine, albeit frequently found.[1][66]

Autoimmunity has been proposed to be a factor in ME/CFS. There is a subset of people with ME with increased B cell activity and autoantibodies, possibly as a result of decreased NK cell regulation or viral mimicry.[67] In 2015, a large German study found 29% of people with ME/CFS had elevated autoantibodies to M3 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors as well as to ß2 adrenergic receptors.[68][69][70] Problems with these receptors can lead to impaired blood flow.[70]

Energy metabolism

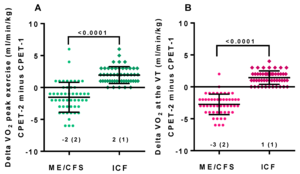

Objective signs of PEM have been found with the 2-day CPET, a test that involves taking VO2max tests on successive days. People with ME/CFS have lower performance and heart rate compared to healthy controls on the first test. On the second test, healthy people's scores stay the same or increase slightly, while people with ME/CFS have a decrease in anaerobic threshold, peak power output, and VO2max. Potential causes include impaired oxygen transport, impaired aerobic metabolism, and mitochondrial dysfunction.[71]

Studies have observed mitochondrial abnormalities in cellular energy production, but heterogeneity among studies make it difficult to draw any conclusions. ME/CFS is likely not a mainly mitochondrial disorder, based on genetic evidence.[72] An example of a possible mitochondrial mechanism in ME/CFS is the overexpression of the WASF3 protein, which reduced mitochrondrial supercomplex formation and thereby cellular energy production.[34]: 8

Other

Evidence points to abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) in some people with ME/CFS, which may include lower cortisol levels, a decrease in the variation of cortisol levels throughout the day and decreased responsiveness of the HPA axis. This can be considered to be a "HPA axis phenotype" that is also present in some other conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder and some autoimmune conditions.[73] In most healthy adults, the cortisol awakening response shows an increase in cortisol levels averaging 50% in the first half-hour after waking. In people with CFS, this increase apparently is significantly less, but methods of measuring cortisol levels vary, so this is not certain.[74]

Other abnormalities have been proposed are reduced blood flow to the brain under orthostatic stress (as found in a tilt table test), small-fibre neuropathy, and an increase in the amount of gut microbes entering the blood.[34]: 9

Diagnosis

No characteristic laboratory abnormalities are approved to diagnose ME/CFS; while physical abnormalities can be found, no single finding is considered sufficient for diagnosis.[15][18] Blood, urine, and other tests are used to rule out other conditions that could be responsible for the symptoms.[75][76][1] A diagnosis may further include taking a medical history and a mental and physical examination.[75]

Diagnostic tools

The CDC recommends considering the questionnaires and tools described in the 2015 Institute of Medicine report, which include:[77]

- DePaul Symptom Questionnaire

- CDC Symptom Inventory for CFS

- The Chalder Fatigue Scale

- The Krupp Fatigue Severity Scale

- Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)

- SF-36 / RAND-36

- Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[1]: 270

A two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) is not necessary for diagnosis, although lower readings on the second day may be helpful in supporting a claim for Social Security disability. A two-day CPET cannot be used to rule out ME/CFS.[1]: 216 Orthostatic intolerance can be measured with a tilt table test, or if that is unavaible, using the simpler NASA 10-minute lean test.[15]

Definitions

Many sets of diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS have been proposed. Required symptoms vary. The four most commly cited are post-exertional malaise, fatigue, cognitive impairment, and sleep disruption.

Notable definitions include:[31][33]

- The 2021 UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines employ a definition of ME/CFS that requires severe fatigue, post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep or sleep disturbance, and cognitive difficulties.[78]

- The 2015 definition by the National Academy of Medicine (then referred to as the "Institute of Medicine") is not a definition of exclusion (differential diagnosis is still required).[1] "Diagnosis requires that the patient have the following three symptoms: 1) A substantial reduction or impairment in the ability to engage in pre-illness levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, that persists for more than 6 months and is accompanied by fatigue, which is often profound, is of new or definite onset (not lifelong), is not the result of ongoing excessive exertion, and is not substantially alleviated by rest, and 2) post-exertional malaise 3) Unrefreshing sleep; At least one of the two following manifestations is also required: 1) Cognitive impairment 2) Orthostatic intolerance"[1]

- The Myalgic Encephalomyelitis International Consensus Criteria (ICC) published in 2011 is based on the Canadian working definition.[79][7] The ICC does not have a six months waiting time for diagnosis. The ICC requires post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion (PENE) which has similarities with post-exertional malaise, plus at least three neurological symptoms, at least one immune or gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptom, and at least one energy metabolism or ion transportation symptom. Unrefreshing sleep or sleep dysfunction, headaches or other pain, and problems with thinking or memory, and sensory or movement symptoms are all required under the neurological symptoms criterion.[79] Patients with post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion but only partially meeting the criteria are given the diagnosis of atypical myalgic encephalomyelitis.[79]

- The 2003 Canadian consensus criteria[80] state: "A patient with ME/CFS will meet the criteria for fatigue, post-exertional malaise and/or fatigue, sleep dysfunction, and pain; have two or more neurological/cognitive manifestations and one or more symptoms from two of the categories of autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune manifestations; and the illness persists for at least 6 months".

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition (1994),[81] is also called the Fukuda definition and is a revision of the Holmes or CDC 1988 scoring system.[82] The 1994 criteria require the presence of four or more symptoms beyond fatigue, while the 1988 criteria require six to eight.[83]

Differential diagnosis

Certain medical conditions have similar symptoms as ME/CFS and should be evaluated before a diagnosis of ME/CFS can be confirmed. While alternative diagnoses are explored, advice can be given on symptom management, to avoid delays in care.[78] Post-exertional malaise often acts as a distinguishing feature of ME/CFS. A diagnosis of ME/CFS is only confirmed after six months of symptoms, to exclude acute medical conditions or problems related to lifestyle, which may resolve within that time frame.[15]

Examples of possible differential diagnoses span a large set of specialties, and depend on patient history.[15] Examples are infectious diseases (such as Epstein–Barr virus, HIV infection, tuberculosis, Lyme disease), neuroendocrine disorder (such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, Addison's disease, adrenal insufficiency), blood disorders (such as anemia) and some cancers. Various rheumatological and auto-immune diseases may also have overlapping symptoms with ME/CFS, such as Sjögren's syndrome, lupus and arthritis. Furthermore, evaluation of psychiatric diseases (such as depression, substance use disorder and anorexia nervosa) and neurological disorders (such as obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, Parkinson's, multiple sclerosis, craniocervical instability) may be warranted.[15][33] Finally, sleep disorders, coeliac disease, connective tissue disorders and side effects of medications may also explain symptoms.[85]

Joint and muscle pain without swelling or inflammation is a feature of ME/CFS, but is more associated with fibromyalgia. Modern definitions of fibromyalgia not only include widespread pain, but also fatigue, sleep disturbances and cognitive issues, making the two syndromes difficult to distinguish.[86]: 13, 26 The two are often co-diagnosed.[87] Ehlers–Danlos syndromes (EDS) may also have similar symptoms.[88]

Like with other chronic illnesses, depression and anxiety co-occur frequently with ME/CFS. Depression may be differentially diagnosed from ME/CFS by feelings of worthlessness, the inability to feel pleasure, loss of interest and/or guilt; and the absence of bodily symptoms such autonomic dysfunction, pain, migraines or post-exertional malaise.[86]: 26

Management

There is no approved drug treatment or cure for ME/CFS, although some symptoms can be treated or managed. The CDC recommends a strategy treating the most disabling symptom first, and the NICE guideline specifies the need for shared decision-making between patients and medical teams.[8][78] Clinical management varies widely, with many patients receiving combinations of therapies.[89]: 9

Pacing, or managing one's activities to stay within energy limits, can reduce episodes of post-exertional malaise. Addressing sleep problems with good sleep hygiene, or medication if required, may be beneficial. Chronic pain is common in ME/CFS, and the CDC recommends consulting with a pain management specialist if over-the-counter painkillers are insufficient. For cognitive impairment, adaptations like organizers and calendars may be helpful.[8]

Symptoms of severe ME/CFS may be misunderstood as neglect or abuse during well-being evaluations, and NICE recommends that professionals with experience in ME/CFS should be involved in any type of assessment for safeguarding.[78]

Co-occurring conditions that may interact with and worsen ME/CFS symptoms are common, and treating these may help manage ME/CFS. Commonly diagnosed ones include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, allergies, and chemical sensitivities.[90] The debilitating nature of ME/CFS can cause depression, anxiety or other psychological problems, which should be treated accordingly.[8]

Pacing and energy envelope

Pacing, or activity management, is a management strategy based on the observation that symptoms tend to increase following mental or physical exertion.[8] It was developed for ME/CFS in the 1980s,[91] and is now commonly used as a management strategy in chronic illnesses and in chronic pain.[92]

Its two forms are symptom-contingent pacing, in which the decision to stop (and rest or change an activity) is determined by self-awareness of an worsening of symptoms, and time-contingent pacing, which is determined by a set schedule of activities that a patient estimates they can complete without triggering post-exertional malaise (PEM). Thus, the principle behind pacing for ME/CFS is to avoid overexertion and an exacerbation of symptoms. It is not aimed at treating the illness as a whole. Those whose illness appears stable may gradually increase activity and exercise levels, but according to the principle of pacing, must rest or reduce their activity levels if it becomes clear that they have exceeded their limits.[91][19]

Energy envelope theory, consistent with pacing, states that patients should stay within, and avoid pushing through, the envelope of energy available to them, so as to reduce the post-exertional malaise "payback" caused by overexertion. This may help them make "modest gains" in physical functioning.[93][94] Use of a heart-rate monitor with pacing to monitor and manage activity levels is recommended by a number of patient groups,[95] and the CDC considers it useful for some individuals to help avoid post-exertional malaise.[8]

Several studies have found energy envelope theory to be a helpful management strategy, noting that it reduces symptoms and may increase the level of functioning in ME/CFS.[94] A 2023 review of pacing studies stated that while most trials found a positive effects, studies were typically small and rarely included a way to tell if patients implemented pacing well. It said that until large RCTs are undertaken, the literature base is insufficient to inform treatment practises.[96]

Exercise

Stretching, movement therapies, and toning exercises are recommended for pain in people with ME/CFS. In many chronic illnesses, aerobic exercise is beneficial, but in chronic fatigue syndrome, the CDC does not recommend it. The CDC states:[8]

Any activity or exercise plan for people with ME/CFS needs to be carefully designed with input from each patient. While vigorous aerobic exercise can be beneficial for many chronic illnesses, patients with ME/CFS do not tolerate such exercise routines. Standard exercise recommendations for healthy people can be harmful for patients with ME/CFS. However, it is important that patients with ME/CFS undertake activities that they can tolerate...

Short periods of low-intensity exercise to improve stamina may be possible in a subset of people with ME/CFS. Exercise should only be attempted after pacing has been implemented effectively.[15] The amount of exercise should be varied based on the symptom severity of each day, to avoid PEM.[86]

Graded exercise therapy (GET), a proposed treatment for ME/CFS which involves fixed increments in exercise over time, is not recommended for people with ME/CFS.[40][86]: 37

Counseling

Chronic illness often impacts mental health.[15] Psychotherapy may help people with ME/CFS manage the stress of being ill, apply self-management strategies for their symptoms, and cope with physical pain.[19][8] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may be offered to people with a new ME/CFS diagnosis to give them tools to cope with the disease and help with rehabilitation. A mindfullness approach is sometimes also chosen.[34]: 41

If sleep problems remain after implementing sleep hygiene routines, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia can be offered. Family sessions may be useful to educate people close to those with ME/CFS about the illness' severity.[34]: 41 Depression or anxiety resulting from ME/CFS is common,[15] and CBT may be a useful treatment.[34]: 41

Diet and nutrition

A proper diet is a significant contributor to the health of any individual. Medical consultation about diet and supplements is recommended for persons with ME/CFS.[8] Persons with ME/CFS may also benefit from nutritional support if deficiencies are detected by medical testing. However, nutritional supplements may interact with prescribed medication.[97][8]

Bowel issues are a common symptom of ME/CFS. For some, eliminating certain food groups, such as caffeine, alcohol or dairy, can alleviate symptoms.[15] People with severe ME/CFS may have significant trouble getting nutrition. Intravenous feeding (via blood) or tube feeding may be necessary to address this, or to address electrolyte imbalances.[40]

Changes in environment

People with moderate to severe ME/CFS may benefit from home adaptations and mobility aids, such as wheelchairs, disability parking, shower chairs, or stair lifts. To manage sensitivities to environmental stimuli, these stimuli can be limited. For instance, the use of perfume can be discouraged, or the patient can use an eye mask or earplugs.[34]: 39–40

Proposed treatments

There are no approved treatments for ME/CFS. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) have been proposed, but their safety and efficacy are disputed.[98][99] The drug rintatolimod has been trialed and has been approved in Argentina.[100]

Cognitive behavioral therapy

NICE only recommends CBT for help coping with distress the illness causes. The guidelines emphasize that CBT for people with ME/CFS, not assume unhelpful beliefs cause their illness, and not represent it as curative.[78] Similarly, the CDC stopped recommending CBT as a treatment in 2017, recommending counseling as a coping method instead.[101][8]

Certain types of CBT for ME/CFS operate on the idea that individuals with ME/CFS mistakenly believe their illness is purely physical. According to this model, their fear of triggering symptoms can prolong their condition, creating a harmful cycle of avoiding activity and becoming less physically active. This model has been criticized as lacking evidence and being at odds with the biological changes associated with ME/CFS. The use of this type of CBT has been controversial,[98][99] and NICE removed their recommendation for this form in 2021.[78]

Graded exercise therapy

Graded exercise therapy (GET) is a programme of physical therapy that starts at a patient's baseline and increases over time in fixed increments. Like forms of CBT that seeks to challenge patients beliefs of their illness, it assumes that fear of activity and deconditioning play a significant role in their illness.[78][8] Reviews of GET either see weak evidence of a small to moderate effect[89][102] or no evidence of effectiveness.[98][99] Few clinical trials contained enough detail about adverse effects.[89] There are reports of serious adverse effects from GET.[13]: 160

The 2021 NICE guidelines removed GET as a recommended treatment due to low quality evidence regarding benefit, with the guidelines now telling clinicians not to prescribe "any programme that ... uses fixed incremental increases in physical activity or exercise, for example, graded exercise therapy."[19] The CDC withdrew their recommendation for GET in 2017.[101]

Rintatolimod

Rintatolimod is a double-stranded RNA drug developed to modulate an antiviral immune reaction through activation of toll-like receptor 3. In several clinical trials of ME/CFS, the treatment has shown a reduction in symptoms, but improvements were not sustained after discontinuation.[103] Evidence supporting the use of rintatolimod is deemed low to moderate.[104] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has denied commercial approval, called a new drug application, citing several deficiencies and gaps in safety data in the trials, and concluded that the available evidence is insufficient to demonstrate its safety or efficacy in ME/CFS.[105][106] Rintatolimod has been approved for marketing and treatment for persons with ME/CFS in Argentina.[100]

Prognosis

Information on the prognosis of ME/CFS is limited, and the course of the illness is variable.[107] Complete recovery, partial improvement, and worsening are all possible,[107] but full recovery is rare.[13]: 11 Symptoms generally fluctuate over days, weeks, or longer periods, and some people may experience periods of remission.[108] Overall, "many will need to adapt to living with ME/CFS."[108] Some people who improve need to manage their activities in order to prevent relapse.[107]

An early diagnosis may improve care and prognosis.[33] Factors that may make the disease worse over days but also over longer time periods are physical and mental exertion, a new infection, sleep deprivation, and emotional stress.[13]: 11

Children and teenagers are more likely to recover or improve than adults.[107][108] For instance, a study in Australia among 6- to 18-year olds found two thirds reported recovery after ten years, and that the typical duration of illness was 5 years.[13]: 11

Epidemiology

Reported prevalence rates vary widely depending on how ME/CFS is defined and diagnosed.[10] Based on the 1994 CDC diagnostic criteria, the global prevalence rate for CFS is 0.89%.[10] In comparison, estimates using the 1988 CDC "Holmes" criteria and 2003 Canadian criteria for ME produced an incidence rate of only 0.17%.[10]

As of 2015, between 836,000 and 2.5 million Americans were estimated to have ME/CFS, with 84–91% of these being undiagnosed.[1]: 1 In England and Wales, over 250,000 people are estimated to be affected.[109] The worldwide prevalence is 17 and 24 million.[10] These estimates are based on data before the COVID-19 pandemic. It is likely that numbers have increased as a large share of people with Long COVID meet the diagnostic criteria of ME/CFS.[13]: 29, 228 A 2021–2022 CDC survey found that 1.3% of adults in the United States, or 3.3 million, had ME/CFS.[110]

Females are diagnosed about 1.5 to 2.0 times more often with ME/CFS than males.[10] An estimated 0.5% of children have ME/CFS, and more adolescents are affected with the illness than younger children.[1]: 182 [22] The incidence rate according to age has two peaks, one at 10–19 and another at 30–39 years,[4] and the rate of prevalence is highest between ages 40 and 60.[45][111]

History

From 1934 onwards, there were multiple outbreaks globally of an unfamiliar illness, initially mistaken for polio. A 1950s outbreak at London's Royal Free Hospital led to the term "benign myalgic encephalomyelitis" (ME). Patients displayed symptoms such as malaise, sore throat, pain and signs of nervous system inflammation. While its infectious nature was suspected, the exact cause remained elusive.[1]: 28–29 The syndrome appeared in sporadic as well as epidemic cases.[112]

In 1970, two UK psychiatrists proposed that these ME outbreaks were psychosocial phenomena, suggesting mass hysteria or altered medical perception as potential causes. This theory, though challenged, sparked controversy and cast doubt on ME's legitimacy in the medical community.[1]: 28–29

Melvin Ramsay's subsequent research emphasized ME's disabling nature, prompting the removal of "benign" from the name and the establishment of diagnostic criteria in 1986. These criteria included the tendency of muscles to tire after minor effort and taking multiple days to recover, high symptom variability, and chronicity. Despite Ramsay's efforts and a UK report acknowledging ME as not psychological, skepticism persisted within the medical field, leading to limited research.[1]: 28–29

In the United States, Nevada and New York State saw outbreaks of what appeared similar to mononucleosis in the middle of the 1980s. People suffered from "chronic or recurrent fatigue", among a large number of other symptoms.[1]: 28–29 The initial link of elevated antibodies to the Epstein–Barr virus had the illness acquire the name "chronic Epstein–Barr virus syndrome. The CDC renamed it chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), as a viral cause could not be confirmed in studies.[113]: 155–158 An initial case definition of CFS was defined in 1988;[1]: 28–29 The CDC published new diagnostic criteria in 1994, which became widely referenced.[114]

In the 2010s, ME/CFS gained increasing recognition from health professionals and the public. Two reports proved key in this shift. In 2015, the Institute of Medicine produced a report with new diagnostic criteria, which described ME/CFS as a "serious, chronic, complex systemic disease". The US National Institutes of Health subsequently published their Pathways to Prevention report, which gave recommendations on research priorities.[115]

Society and culture

Naming

Many names have been proposed for the illness. Currently, the most commonly used are "chronic fatigue syndrome", "myalgic encephalomyelitis", and the umbrella term "myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)". Reaching consensus on a name is challenging because the cause and pathology remain unknown.[1]: 29–30

Many patients object to the term "chronic fatigue syndrome". They consider the term too simplistic and trivialising, which in turn prevents the illness from being taken seriously.[1]: 234 [116] At the same time, there are also issues with the use of "myalgic encephalomyelitis, as there is only limited evidence of brain inflammation implied by the name.[86]: 3 The umbrella term ME/CFS would retain the better-known phrase CFS without trivialising the disease, but some people object to this name too as they see CFS and ME as distinct illnesses.[116]

A 2015 report from the Institute of Medicine recommended the illness be renamed "systemic exertion intolerance disease", (SEID), and suggested new diagnostic criteria, proposing post-exertional malaise (PEM), impaired function, and sleep problems are core symptoms of ME/CFS.[1] While the new name was not widely adopted, the diagnostic criteria were taken over by the CDC. Like CFS, SEID only focuses on a single symptom and patient opinions have generally been negative.[117]

Economic and social impact

Loss of health, social development, employment, educational and recreational opportunity, as well as increased utilization and cost of medical care can occur with ME/CFS. The illness often significantly diminishes a person's perception of self, financial security, overall quality of life and can cause isolation from community.[23] The normal development of children with ME/CFS is interrupted, as they increasingly rely on their family for assistance, rather than become more independent with age.[118] Not only patients are impacted, by also their unpaid carers. Caring for somebody with ME/CFS can be a full-time role, and the stress of caregiving is made worse by the lack of effective treatments and by the historical biases.[119]

Economic costs due to ME/CFS are "significant".[120] A 2021 paper by Leonard Jason and Arthur Mirin estimated the impact in the US to be $36–51 billion per year, or $31,592 to $41,630 per person, considering both lost wages and healthcare costs.[121] The CDC estimated direct healthcare costs alone at $9–14 billion annually.[120] A 2017 estimate for the annual economic burden in the United Kingdom was £3.3 billion.[16]

Advocacy

12 May is designated as ME/CFS International Awareness Day.[122] The goal of the day is to raise awareness among the public and health care workers on diagnosis and treatment of ME/CFS.[123] It was chosen because it is the birthday of Florence Nightingale, who had an unidentified illness appearing similar to ME/CFS.[124]

Advocacy and research organisations include MEAction,[125] Open Medicine Foundation[126] and the Solve ME/CFS Initiative in the US,[125] the ME Association in the UK,[127] and the European ME Coalition.[125]

Doctor–patient relations

The NAM report refers to ME/CFS as "stigmatized", and the majority of patients report negative healthcare experiences.[1]: 30 [24] These patients may feel that their doctor inappropriately calls their illness psychological or doubts the severity of their symptoms.[24] They may also feel forced to prove that they are legitimately ill.[128] Some may be given outdated treatments that provoke symptoms or assume their illness is due to unhelpful thoughts and deconditioning.[1]: 25 [15]: 2871 [129] In a 2009 survey, only 35% of patients considered their physicians experienced with CFS and only 23% thought their doctors knew enough to treat it.[130]

Doctors may have trouble managing an illness that lacks a clear cause or treatment.[1]: 30 [24] Clinicians may be unfamiliar with ME/CFS, as it is often not covered in medical school.[129][24] Due to this unfamiliarity, people may go undiagnosed for years,[15]: 2861 [1]: 1 or be misdiagnosed with mental conditions.[129][15]: 2871 A substantial portion of doctors are uncertain about how to diagnose or manage chronic fatigue syndrome.[130] In a 2006 survey of GPs in southwest England, 75% accepted it as a "recognisable clinical entity", but 48% did not feel confident in diagnosing it, and 41% in managing it.[131][130]

Controversy

Much contention has arisen over the cause, pathophysiology,[132] name,[133] and diagnostic criteria of ME/CFS.[26][134] Historically, many professionals within the medical community were unfamiliar with CFS, or did not recognize it as a real condition; nor did agreement exist on its prevalence or seriousness.[135][136][137]

In 1970, two British psychiatrists, McEvedy and Beard, reviewed the case notes of 15 outbreaks of benign ME and concluded it was caused by "mass hysteria on the part of patients, or altered medical perception of the attending physicians."[138] Their conclusions were based on the absence of known causes of symptoms in the patients and a higher prevalence of the illness in females. This perspective was rejected by Melvin Ramsay, who worked as a consultant at the Royal Free Hospital, the center of a significant outbreak.[139][1]: 28 The psychological hypothesis created great controversy, and convinced a generation of health professionals in the UK that this could be a plausible explanation for the condition, resulting in neglect by many medical specialties.[140][141] The specialty that did take a major interest in the illness was psychiatry.[141]

Because of the controversy, sociologists hypothesized that stresses of modern living might be a cause of the illness, while some in the media used the term "Yuppie flu" and called it a disease of the middle class.[141] People with disabilities from CFS were often not believed and were accused of being malingerers.[141] The November 1990 issue of Newsweek ran a cover story on CFS, which although supportive of an organic cause of the illness, also featured the term 'yuppie flu', reflecting the stereotype that CFS mainly affected yuppies. The implication was that CFS is a form of burnout. The term 'yuppie flu' is considered offensive by both patients and clinicians.[142][143]

In 2009, the journal Science[144] published a study that identified the XMRV retrovirus in a population of people with CFS. Other studies failed to reproduce this finding,[145][146][147] and in 2011, the editor of Science formally retracted its XMRV paper[148] while the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences similarly retracted a 2010 paper which had appeared to support the finding of a connection between XMRV and CFS.[149]

Research funding

Historical research funding for ME/CFS has been far below that of comparable diseases.[25][150] In a 2015 report, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences called it "remakabl[e]" how little funding there had been for research into causes, mechanisms and treatment.[1]: 9 Lower funding levels have led to a smaller number and size of studies.[151] In addition, drug companies have invested very little in the disease.[152]

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the largest biomedical funder worldwide.[153] Using rough estimates of disease burden, a study found NIH funding for ME/CFS was only 3% to 7% of the average disease per healthy life year lost between 2015 and 2019.[154] Worldwide, multiple sclerosis, which affects fewer people and results in disability no worse than ME/CFS, received 20 times as much funding between 2007 and 2015.[150]

Multiple reasons have been proposed for the low funding levels. Diseases for which society "blames the victim" are frequently underfunded. This may explain why a severe lung disease often caused by smoking receives low funding per healthy life year lost.[155] Similarly for ME/CFS, the historical belief that it is caused by psychological factors, may have contributed to lower funding. Gender bias may also play a role; the NIH spends less on diseases which predominantly affect women in relation to disease burden. Less well funded research areas may also struggle competing with more mature areas of medicine for the same grants.[154]

Notable cases

In 1989, The Golden Girls (1985–1992) featured chronic fatigue syndrome in a two-episode arc, "Sick and Tired: Part 1" and "Part 2", in which protagonist Dorothy Zbornak, portrayed by Bea Arthur, after a lengthy battle with her doctors in an effort to find a diagnosis for her symptoms, is finally diagnosed with CFS.[156] American author Ann Bannon had CFS.[157] Laura Hillenbrand, author of the popular book Seabiscuit, has struggled with CFS since age 19.[158][159]

Research

Research into ME/CFS seeks to find a better understanding of the disease's causes, biomarkers to aid in diagnosis, and treatments to relieve symptoms.[1]: 10 The emergence of long COVID has sparked increased interest in ME/CFS, as the two conditions may share pathology, and a treatment for one may treat the other.[29]

Causes

Recent research suggests dysfunction in many biological processes. These changes may share a common cause, but the true relationship between them is currently unknown. Metabolic areas of interest include disruptions in amino acid metabolism, the TCA cycle, ATP synthesis, and potentially increased lipid metabolism. Other research has investigated immune dysregulation and its potential connections to mitochondrial dysfunction. Autoimmunity has been proposed as a cause, but evidence is scant. People with ME/CFS may have abnormal gut microbiota, which has been proposed to affect mitochondria or nervous system function.[160]

Several small studies have investigated the genetics of ME/CFS, but none of their findings have been replicated.[16] A larger study, DecodeME, is currently underway in the United Kingdom.[161]

Treatments

Various drug treatments for ME/CFS are being explored. The types of drugs under investigation often target the nervous system, the immune system, autoimmunity, or pain directly. More recently, there has been a growing interest in drugs targeting energy metabolism.[152]

Drugs targetting the immune system include rintatolimod.[152] Low-dose naltrexone, which works against neuro-inflammation, is being studied as of 2023.[162] Rituximab, a drug that depletes B cells, was studied and found to be ineffective.[160] Other options targetting auto-immunity are immune absorption, whereby a large set of (auto)antibodies is removed from the blood.[152]

Biomarkers

Many biomarkers for ME/CFS have been proposed, but there is no consensus on a biomarker as of yet. The search for biomarkers is complicated due to the historical dominance of the broad Fukuda criteria. Studies on biomarkers have often been too small to draw robust conclusions. NK cells have been identified as an area of interest for biomarker research, as they show consistent abnormalities.[18] Other proposed markers include electrical measurements of blood cells and a combination of immune cell death rate and function.[162]

Challenges

ME/CFS affects multiple bodily systems, varies widely in severity, and fluctuates over time, creating heterogeneity within patient groups and making it very difficult to identify a singular cause. This variation may also cause treatments that are effective for some to have no effect or a negative effect in others.[162] Dividing people with ME/CFS into subtypes may help manage this heterogeneity.[160]

The existence of multiple diagnostic criteria, and variations in how scientists apply them, complicate comparisons between studies.[1]: 53 [160] Some definitions, like the Oxford and Fukuda criteria, may fail to distinguish between chronic fatigue in general and ME/CFS, which requires PEM in modern definitions.[160] Definitions also vary in which co-occurring conditions preclude a diagnosis of ME/CFS.[1]: 52

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine (10 February 2015). Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness (PDF). PMID 25695122. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations – Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management – Guidance". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 29 October 2021. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Collard SS, Murphy J (September 2020). "Management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis in a pediatric population: A scoping review". Journal of Child Health Care. 24 (3): 411–431. doi:10.1177/1367493519864747. PMC 7863118. PMID 31379194.

- ↑ "Information for the public | Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 29 October 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Possible Causes". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, et al. (International Consensus Panel) (2012). "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis – Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2020.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 "Treatment of ME/CFS". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 January 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sandler CX, Lloyd AR (May 2020). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: progress and possibilities". The Medical Journal of Australia. 212 (9): 428–433. doi:10.5694/mja2.50553. PMID 32248536. S2CID 214810583.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 Lim EJ, Ahn YC, Jang ES, Lee SW, Lee SH, Son CG (February 2020). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME)". Journal of Translational Medicine. 18 (1): 100. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02269-0. PMC 7038594. PMID 32093722.

- ↑ "Information for Healthcare Providers". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 "Symptoms of ME/CFS". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG) (17 April 2023). Myalgische Enzephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Aktueller Kenntnisstand [Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): current state of knowledge] (PDF) (in Deutsch). Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen. ISSN 1864-2500. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 "Etiology and Pathophysiology". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 12 July 2018. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 15.15 15.16 Bateman L, Bested AC, Bonilla HF, Chheda BV, Chu L, Curtin JM, et al. (November 2021). "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Essentials of Diagnosis and Management". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 96 (11): 2861–2878. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.004. PMID 34454716. S2CID 237419583.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Dibble JJ, McGrath SJ, Ponting CP (September 2020). "Genetic risk factors of ME/CFS: a critical review". Human Molecular Genetics. 29 (R1): R117–R124. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddaa169. PMC 7530519. PMID 32744306.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Maksoud R, du Preez S, Eaton-Fitch N, Thapaliya K, Barnden L, Cabanas H, et al. (2020). "A systematic review of neurological impairments in myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome using neuroimaging techniques". PLOS ONE. 15 (4): e0232475. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1532475M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232475. PMC 7192498. PMID 32353033.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Maksoud R, Magawa C, Eaton-Fitch N, Thapaliya K, Marshall-Gradisnik S (May 2023). "Biomarkers for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): a systematic review". BMC Medicine. 21 (1): 189. doi:10.1186/s12916-023-02893-9. PMID 37226227.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 "Recommendations – Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management – Guidance". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 29 October 2021. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ Estévez-López F, Mudie K, Wang-Steverding X, Bakken IJ, Ivanovs A, Castro-Marrero J, et al. (May 2020). "Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Burden of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Across Europe: Current Evidence and EUROMENE Research Recommendations for Epidemiology". Journal of Clinical Medicine. MDPI AG. 9 (5): 1557. doi:10.3390/jcm9051557. PMC 7290765. PMID 32455633.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Epidemiology". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 12 July 2018. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "ME/CFS in Children". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

ME/CFS is often thought of as a problem in adults, but children (both adolescents and younger children) can also get ME/CFS.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Boulazreg S, Rokach A (October 2020). "The Lonely, Isolating, and Alienating Implications of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Healthcare. 8 (4): 413. doi:10.3390/healthcare8040413. PMC 7711762. PMID 33092097.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 McManimen S, McClellan D, Stoothoff J, Gleason K, Jason LA (March 2019). "Dismissing chronic illness: A qualitative analysis of negative health care experiences". Health Care for Women International. 40 (3): 241–258. doi:10.1080/07399332.2018.1521811. PMC 6567989. PMID 30829147.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Tyson S, Stanley K, Gronlund TA, Leary S, Emmans Dean M, Dransfield C, et al. (2022). "Research priorities for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): the results of a James Lind alliance priority setting exercise". Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior. 10 (4): 200–211. doi:10.1080/21641846.2022.2124775. ISSN 2164-1846. S2CID 252652429.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 O'Leary D (July 2019). "Ethical classification of ME/CFS in the United Kingdom". Bioethics. 33 (6): 716–722. doi:10.1111/bioe.12559. PMID 30734339. S2CID 73450577.

- ↑ Bateman L (2022). "Fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome". In Zigmond M, Wiley C, Chesselet MF (eds.). Neurobiology of Brain Disorders : Biological Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 564. ISBN 9780323856546.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Shan ZY, Barnden LR, Kwiatek RA, Bhuta S, Hermens DF, Lagopoulos J (September 2020). "Neuroimaging characteristics of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): a systematic review". Journal of Translational Medicine. 18 (1): 335. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02506-6. PMC 7466519. PMID 32873297.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Marshall-Gradisnik S, Eaton-Fitch N (September 2022). "Understanding myalgic encephalomyelitis". Science. 377 (6611): 1150–1151. Bibcode:2022Sci...377.1150M. doi:10.1126/science.abo1261. hdl:10072/420658. PMID 36074854. S2CID 252159772.

- ↑ "8E49 Postviral fatigue syndrome". ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

Diseases of the nervous system

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Lim EJ, Son CG (July 2020). "Review of case definitions for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)". Journal of Translational Medicine. 18 (1): 289. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02455-0. PMC 7391812. PMID 32727489.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Treating the Most Disruptive Symptoms First and Preventing Worsening of Symptoms". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 National Guideline Centre (UK) (2021). Identifying and diagnosing ME/CFS: Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy) / chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management: Evidence review D. NICE Evidence Reviews Collection. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). ISBN 978-1-4731-4221-3. PMID 35438857. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ↑ 34.00 34.01 34.02 34.03 34.04 34.05 34.06 34.07 34.08 34.09 34.10 Baraniuk JN, Marshall-Gradisnik S, Eaton-Fitch N (January 2024). BMJ Best Practice: Myalgic encephalomyelitis (Chronic fatigue syndrome) (PDF). BMJ Publishing Group. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ↑ Christley Y, Duffy T, Everall IP, Martin CR (April 2013). "The neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological features of chronic fatigue syndrome: revisiting the enigma". Current Psychiatry Reports. 15 (4): 353. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0353-8. PMID 23440559. S2CID 25790262.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Cvejic E, Birch RC, Vollmer-Conna U (May 2016). "Cognitive Dysfunction in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a Review of Recent Evidence". Current Rheumatology Reports. 18 (5): 24. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0577-9. PMID 27032787. S2CID 38748839.

- ↑ Nijs J, Meeus M, Van Oosterwijck J, Ickmans K, Moorkens G, Hans G, De Clerck LS (February 2012). "In the mind or in the brain? Scientific evidence for central sensitisation in chronic fatigue syndrome". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 42 (2): 203–212. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02575.x. PMID 21793823. S2CID 13926525.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 O'Boyle S, Nacul L, Nacul FE, Mudie K, Kingdon CC, Cliff JM, et al. (2021). "A Natural History of Disease Framework for Improving the Prevention, Management, and Research on Post-viral Fatigue Syndrome and Other Forms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Frontiers in Medicine. 8: 688159. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.688159. PMC 8835111. PMID 35155455.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 "Presentation and Clinical Course of ME/CFS". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Grach SL, Seltzer J, Chon TY, Ganesh R (October 2023). "Diagnosis and Management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 98 (10): 1544–1551. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.032. PMID 37793728. S2CID 263665180.

- ↑ Grach SL, Seltzer J, Chon TY, Ganesh R (October 2023). "Diagnosis and Management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 98 (10): 1544–1551. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.032. PMID 37793728. S2CID 263665180.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Montoya JG, Dowell TG, Mooney AE, Dimmock ME, Chu L (October 2021). "Caring for the Patient with Severe or Very Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Healthcare. 9 (10): 1331. doi:10.3390/healthcare9101331. PMC 8544443. PMID 34683011.

- ↑ Unger ER, Lin JS, Brimmer DJ, Lapp CW, Komaroff AL, Nath A, et al. (December 2016). "CDC Grand Rounds: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Advancing Research and Clinical Education" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (50–51): 1434–1438. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051a4. PMID 28033311. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

The highest prevalence of illness is in persons aged 40–50 years...

- ↑ Falk Hvidberg M, Brinth LS, Olesen AV, Petersen KD, Ehlers L (6 July 2015). Furlan R (ed.). "The Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0132421. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1032421F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132421. PMC 4492975. PMID 26147503.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 Unger ER, Lin JS, Brimmer DJ, Lapp CW, Komaroff AL, Nath A, et al. (December 2016). "CDC Grand Rounds: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Advancing Research and Clinical Education" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (50–51): 1434–1438. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051a4. PMID 28033311. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

The highest prevalence of illness is in persons aged 40–50 years...

- ↑ "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Etiology and Pathophysiology". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ↑ "Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)". Department of Health, State Government of Victoria, Australia. 7 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ↑ Rasa S, Nora-Krukle Z, Henning N, Eliassen E, Shikova E, Harrer T, et al. (October 2018). "Chronic viral infections in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)". Journal of Translational Medicine. 16 (1): 268. doi:10.1186/s12967-018-1644-y. PMC 6167797. PMID 30285773.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 50.0 50.1 "What is ME/CFS?". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 12 July 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ↑ Dinos S, Khoshaba B, Ashby D, White PD, Nazroo J, Wessely S, Bhui KS (December 2009). "A systematic review of chronic fatigue, its syndromes and ethnicity: prevalence, severity, co-morbidity and coping". International Journal of Epidemiology. 38 (6): 1554–1570. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp147. PMID 19349479.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Hwang JH, Lee JS, Oh HM, Lee EJ, Lim EJ, Son CG (October 2023). "Evaluation of viral infection as an etiology of ME/CFS: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Translational Medicine. 21 (1): 763. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04635-0. PMID 37898798.

- ↑ Ruiz-Pablos M, Paiva B, Zabaleta A (September 2023). "Epstein-Barr virus-acquired immunodeficiency in myalgic encephalomyelitis-Is it present in long COVID?". Journal of Translational Medicine. 21 (1): 633. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04515-7. PMID 37718435.

- ↑ Eriksen W (16 August 2018). "ME/CFS, case definition, and serological response to Epstein–Barr virus. A systematic literature review". Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior. 6 (4): 220–34. doi:10.1080/21641846.2018.1503125. S2CID 80898744.

The levels of antibodies to EBV in ME/CFS patients differed from those in controls in 14 studies. The differences in EBV serology that were revealed, were almost exclusively signs that may indicate higher EBV activity in the patient group. The serological differences between patients and controls were seen in the two studies in which ME/CFS was defined using the Canadian criteria, in 5 of the 9 studies using the Holmes criteria, in 1 of the 2 studies using modified Holmes criteria, in 2 of the 6 studies using the Fukuda criteria, and in 4 of the 7 studies using less known criteria. The single study using the Oxford criteria showed no difference between cases and controls. Conclusions: There seems to be increased EBV activity in subset(s) of ME/CFS patients.

- ↑ Jason LA, Porter N, Brown M, Anderson V, Brown A, Hunnell J, Lerch A (2009). "CFS: A Review of Epidemiology and Natural History Studies". Bulletin of the IACFS/ME. 17 (3): 88–106. PMC 3021257. PMID 21243091.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Hulme K, Hudson JL, Rojczyk P, Little P, Moss-Morris R (August 2017). "Biopsychosocial risk factors of persistent fatigue after acute infection: A systematic review to inform interventions" (PDF). Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 99: 120–129. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.013. PMID 28712416. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ↑ Lee JS, Sato W, Son CG (November 2023). "Brain-regional characteristics and neuroinflammation in ME/CFS patients from neuroimaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 23 (2): 103484. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2023.103484. PMID 38016575.

- ↑ VanElzakker MB, Brumfield SA, Lara Mejia PS (2019). "Neuroinflammation and Cytokines in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): A Critical Review of Research Methods". Frontiers in Neurology. 9: 1033. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.01033. PMC 6335565. PMID 30687207.

- ↑ Tanaka M, Tajima S, Mizuno K, Ishii A, Konishi Y, Miike T, Watanabe Y (November 2015). "Frontier studies on fatigue, autonomic nerve dysfunction, and sleep-rhythm disorder". The Journal of Physiological Sciences. 65 (6): 483–498. doi:10.1007/s12576-015-0399-y. PMC 4621713. PMID 26420687.

- ↑ Mohamed AZ, Andersen T, Radovic S, Del Fante P, Kwiatek R, Calhoun V, Bhuta S, Hermens DF, Lagopoulos J, Shan ZY (June 2023). "Objective sleep measures in chronic fatigue syndrome patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 69: 101771. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101771. PMID 36948138.

- ↑ Van Cauwenbergh D, Nijs J, Kos D, Van Weijnen L, Struyf F, Meeus M (May 2014). "Malfunctioning of the autonomic nervous system in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic literature review". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 44 (5): 516–526. doi:10.1111/eci.12256. PMID 24601948. S2CID 9722415.

- ↑ Eaton-Fitch N, du Preez S, Cabanas H, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S (November 2019). "A systematic review of natural killer cells profile and cytotoxic function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome". Systematic Reviews. 8 (1): 279. doi:10.1186/s13643-019-1202-6. PMC 6857215. PMID 31727160.

- ↑ Nijs J, Nees A, Paul L, De Kooning M, Ickmans K, Meeus M, Van Oosterwijck J (2014). "Altered immune response to exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic literature review". Exercise Immunology Review. 20: 94–116. PMID 24974723.

- ↑ Armstrong CW, McGregor NR, Butt HL, Gooley PR (2014). "Metabolism in chronic fatigue syndrome". Advances in Clinical Chemistry. 66: 121–172. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801401-1.00005-0. ISBN 978-0-12-801401-1. PMID 25344988.

- ↑ Morris G, Anderson G, Galecki P, Berk M, Maes M (March 2013). "A narrative review on the similarities and dissimilarities between myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and sickness behavior". BMC Medicine. 11: 64. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-64. PMC 3751187. PMID 23497361.

- ↑ Griffith JP, Zarrouf FA (2008). "A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don't assume it's depression". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 10 (2): 120–128. doi:10.4088/pcc.v10n0206. PMC 2292451. PMID 18458765.

- ↑ Morris G, Berk M, Galecki P, Maes M (April 2014). "The emerging role of autoimmunity in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/cfs)". Molecular Neurobiology. 49 (2): 741–756. doi:10.1007/s12035-013-8553-0. hdl:11343/219795. PMID 24068616. S2CID 13185036.

- ↑ Loebel M, Grabowski P, Heidecke H, Bauer S, Hanitsch LG, Wittke K, et al. (February 2016). "Antibodies to β adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 52: 32–39. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2015.09.013. PMID 26399744.

- ↑ Sotzny F, Blanco J, Capelli E, Castro-Marrero J, Steiner S, Murovska M, Scheibenbogen C, et al. (European Network on ME/CFS (EUROMENE)) (June 2018). "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Evidence for an autoimmune disease". Autoimmunity Reviews. 17 (6): 601–609. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.009. PMID 29635081.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Wirth K, Scheibenbogen C (June 2020). "A Unifying Hypothesis of the Pathophysiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Recognitions from the finding of autoantibodies against ß2-adrenergic receptors". Autoimmunity Reviews. 19 (6): 102527. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102527. PMID 32247028.

- ↑ Franklin JD, Graham M (3 July 2022). "Repeated maximal exercise tests of peak oxygen consumption in people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior. 10 (3): 119–135. doi:10.1080/21641846.2022.2108628. ISSN 2164-1846. S2CID 251636593.

- ↑ Holden S, Maksoud R, Eaton-Fitch N, Cabanas H, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S (July 2020). "A systematic review of mitochondrial abnormalities in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome/systemic exertion intolerance disease". Journal of Translational Medicine. 18 (1): 290. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02452-3. PMC 7392668. PMID 32727475.

- ↑ Morris G, Anderson G, Maes M (November 2017). "Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways". Molecular Neurobiology. 54 (9): 6806–6819. doi:10.1007/s12035-016-0170-2. PMID 27766535. S2CID 3524276.

- ↑ Powell DJ, Liossi C, Moss-Morris R, Schlotz W (November 2013). "Unstimulated cortisol secretory activity in everyday life and its relationship with fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review and subset meta-analysis". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 38 (11): 2405–2422. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.004. hdl:2164/3290. PMID 23916911.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 "Diagnosis of ME/CFS". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ↑ Bansal AS (July 2016). "Investigating unexplained fatigue in general practice with a particular focus on CFS/ME". BMC Family Practice. 17 (81): 81. doi:10.1186/s12875-016-0493-0. PMC 4950776. PMID 27436349.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (2015). "Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Redefining an Illness. Report for Clinicians" (PDF). Institute of Medicine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.