Vascular dementia

| Vascular dementia | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Arteriosclerotic dementia, multi-infarct dementia, vascular cognitive impairment | |

| |

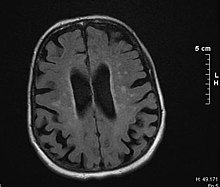

| Brain atrophy on MRI from vascular dementia | |

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry |

| Usual onset | 60 to 75 years old[1] |

| Duration | Long-term[2] |

| Types | Binswanger disease, mixed dementia, subcortical, multi infarct |

| Risk factors | Hyperlipidemia, high blood pressure, diabetes, tobacco use[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Cognitive testing, medical imaging[2][1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Alzheimer's, depression, thyroid disorder, medications (benzodiazepines or anticholinergics), alcohol misuse, neurosyphilis, delirium[2][1] |

| Prevention | Healthy diet, exercise, not smoking, healthy weight, alcohol in moderation[1] |

| Prognosis | Shorter life expectancy[2] |

| Frequency | 16% of dementia cases[2] |

Vascular dementia (VaD) is long-term, progressive cognitive decline due to insufficient blood flow to the brain.[2] It can effect memory, executive function, spatial abilities, language, or attention.[2] Onset may be gradual, sudden, or stepwise in nature.[2] Other symptoms may include paranoia and hallucinations.[2] Complications may include falls, aspiration pneumonia, and pressure sores.[2] Associated condition may include heart disease.[2]

Risk factors include hyperlipidemia, high blood pressure, diabetes, and tobacco use.[2] The underlying mechanism may involved atherosclerosis, thrombosis, or vasculopathy.[2] Diagnosis often requiring speaking with the people who support the affected person and may be supported by cognitive testing and medical imaging.[2][1] Other causes should be ruled out.[2]

There is no cure.[2] Treatment involves preventing worsening by addressing risk factors and efforts to improve behavior.[2] Cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine may help.[2] In those with evidence of a stroke, aspirin, warfarin, or carotid endarterectomy may help.[2] Life expectancy is shortened.[2]

Vascular dementia represents about 16% of dementia cases, being the second most common cause after Alzheimer's.[2][3] It becomes more common with age, with a typical onset between 60 and 75.[2][1] Males are more commonly affected than females.[1] That strokes can result in dementia has been described since the 1800s.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Differentiating dementia syndromes can be challenging, due to the frequently overlapping clinical features and related underlying pathology. In particular, Alzheimer's dementia often co-occurs with vascular dementia.[5]

People with vascular dementia present with progressive cognitive impairment, acutely or subacutely as in mild cognitive impairment, frequently step-wise, after multiple cerebrovascular events (strokes). Some people may appear to improve between events and decline after further silent strokes. A rapidly deteriorating condition may lead to death from a stroke, heart disease, or infection.[6]

Signs and symptoms are cognitive, motor, behavioral, and for a significant proportion of patients also affective. These changes typically occur over a period of 5–10 years. Signs are typically the same as in other dementias, but mainly include cognitive decline and memory impairment of sufficient severity as to interfere with activities of daily living, sometimes with presence of focal neurologic signs, and evidence of features consistent with cerebrovascular disease on brain imaging (CT or MRI).[7] The neurologic signs localizing to certain areas of the brain that can be observed are hemiparesis, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, extensor plantar reflexes, ataxia, pseudobulbar palsy, as well as gait problems and swallowing difficulties. People have patchy deficits in terms of cognitive testing. They tend to have better free recall and fewer recall intrusions when compared with patients with Alzheimer's disease. In the more severely affected patients, or patients affected by infarcts in Wernicke's or Broca's areas, specific problems with speaking called dysarthrias and aphasias may be present.

In small vessel disease, the frontal lobes are often affected. Consequently, patients with vascular dementia tend to perform worse than their Alzheimer's disease counterparts in frontal lobe tasks, such as verbal fluency, and may present with frontal lobe problems: apathy, abulia (lack of will or initiative), problems with attention, orientation, and urinary incontinence. They tend to exhibit more perseverative behavior. VaD patients may also present with general slowing of processing ability, difficulty shifting sets, and impairment in abstract thinking. Apathy early in the disease is more suggestive of vascular dementia.

Rare genetic disorders that cause vascular lesions in the brain have other presentation patterns. As a rule, they tend to occur earlier in life and have a more aggressive course. In addition, infectious disorders, such as syphilis, can cause arterial damage, strokes, and bacterial inflammation of the brain.

Causes

Vascular dementia can be caused by ischemic or hemorrhagic infarcts affecting multiple brain areas, including the anterior cerebral artery territory, the parietal lobes, or the cingulate gyrus. On rare occasion, infarcts in the hippocampus or thalamus are the cause of dementia.[8] A history of stroke increases the risk of developing dementia by around 70%, and recent stroke increases the risk by around 120%.[9] Brain vascular lesions can also be the result of diffuse cerebrovascular disease, such as small vessel disease.[citation needed]

Risk factors for vascular dementia include age, hypertension, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease. Other risk factors include geographic origin, genetic predisposition, and prior strokes.[10]

Vascular dementia can sometimes be triggered by cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which involves accumulation of beta amyloid plaques in the walls of the cerebral arteries, leading to breakdown and rupture of the vessels. Since amyloid plaques are a characteristic feature of Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia may occur as a consequence. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy can, however, appear in people with no prior dementia condition. Amyloid beta accumulation is often present in cognitively normal elderly people.[11][12]

Two reviews of 2018 and 2019 found potentially an association between celiac disease and vascular dementia.[13][14]

Diagnosis

Several specific diagnostic criteria can be used to diagnose vascular dementia,[15] including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) criteria, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke criteria, Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN) criteria,[16] the Alzheimer's Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Center criteria, and the Hachinski Ischemic Score (after Vladimir Hachinski).[17]

The recommended investigations for cognitive impairment include: blood tests (for anemia, vitamin deficiency, thyrotoxicosis, infection, etc.), chest X-Ray, ECG, and neuroimaging, preferably a scan with a functional or metabolic sensitivity beyond a simple CT or MRI. When available as a diagnostic tool, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) neuroimaging may be used to confirm a diagnosis of multi-infarct dementia in conjunction with evaluations involving mental status examination.[18] In a person already having dementia, SPECT appears to be superior in differentiating multi-infarct dementia from Alzheimer's disease, compared to the usual mental testing and medical history analysis.[19] Advances have led to the proposal of new diagnostic criteria.[20][21]

The screening blood tests typically include full blood count, liver function tests, thyroid function tests, lipid profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C reactive protein, syphilis serology, calcium serum level, fasting glucose, urea, electrolytes, vitamin B-12, and folate. In selected patients, HIV serology and certain autoantibody testing may be done.

Mixed dementia is diagnosed when people have evidence of Alzheimer's disease and cerebrovascular disease, either clinically or based on neuro-imaging evidence of ischemic lesions.

Pathology

Gross examination of the brain may reveal noticeable lesions and damage to blood vessels. Accumulation of various substances such as lipid deposits and clotted blood appear on microscopic views. The white matter is most affected, with noticeable atrophy (tissue loss), in addition to calcification of the arteries. Microinfarcts may also be present in the gray matter (cerebral cortex), sometimes in large numbers. Although atheroma of the major cerebral arteries is typical in vascular dementia, smaller vessels and arterioles are mainly affected.

Prevention

Early detection and accurate diagnosis are important,[22] as vascular dementia is at least partially preventable. Ischemic changes in the brain are irreversible, but the patient with vascular dementia can demonstrate periods of stability or even mild improvement.[23] Since stroke is an essential part of vascular dementia,[9] the goal is to prevent new strokes. This is attempted through reduction of stroke risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high blood lipid levels, atrial fibrillation, or diabetes mellitus. Meta-analyses have found that medications for high blood pressure are effective at prevention of pre-stroke dementia, which means that high blood pressure treatment should be started early.[24] These medications include angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, sympathetic nerve inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists or adrenergic antagonists. Elevated lipid levels, including HDL, were found to increase risk of vascular dementia. However, six large recent reviews showed that therapy with statin drugs was ineffective in treatment or prevention of this dementia.[24][25] Aspirin is a medication that is commonly prescribed for prevention of strokes and heart attacks; it is also frequently given to patients with dementia. However, its efficacy in slowing progression of dementia or improving cognition has not been supported by studies.[24][26] Smoking cessation and Mediterranean diet have not been found to help patients with cognitive impairment; physical activity was consistently the most effective method of preventing cognitive decline.[24]

Treatment

Currently, there are no medications that have been approved specifically for prevention or treatment of vascular dementia. The use of medications for treatment of Alzheimer's dementia, such as cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, has shown small[quantify] improvement of cognition in vascular dementia. This is most likely due to the drugs' actions on co-existing AD-related pathology. Multiple studies found a small[quantify] benefit in VaD treatment with: memantine, a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist; cholinesterase inhibitors galantamine, donepezil, rivastigmine;[27] and ginkgo biloba extract.[24]

In those with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity, a strict gluten-free diet may relieve symptoms of mild cognitive impairment.[14][13] It should be started as soon as possible. There is no evidence that a gluten free diet is useful against advanced dementia. People with no digestive symptoms are less likely to receive early diagnosis and treatment.[14]

General management of dementia includes referral to community services, aid with judgment and decision-making regarding legal and ethical issues (e.g., driving, capacity, advance directives), and consideration of caregiver stress. Behavioral and affective symptoms deserve special consideration in this patient group. These problems tend to resist conventional psychopharmacological treatment, and often lead to hospital admission and placement in permanent care.

Prognosis

Many studies have been conducted to determine average survival of patients with dementia. The studies were frequently small and limited, which caused contradictory results in the connection of mortality to the type of dementia and the patient's gender. A very large study conducted in Netherlands in 2015 found that the one-year mortality was three to four times higher in patients after their first referral to a day clinic for dementia, when compared to the general population.[28] If the patient was hospitalized for dementia, the mortality was even higher than in patients hospitalized for cardiovascular disease.[28] Vascular dementia was found to have either comparable or worse survival rates when compared to Alzheimer's Disease;[29][30][31] another very large 2014 Swedish study found that the prognosis for VaD patients was worse for male and older patients.[32]

Unlike Alzheimer's disease, which weakens the patient, causing them to succumb to bacterial infections like pneumonia, vascular dementia can be a direct cause of death due to the possibility of a fatal interruption in the brain's blood supply.

Epidemiology

Vascular dementia is the second-most-common form of dementia after Alzheimer's disease (AD) in older adults.[33][34] The prevalence of the illness is 1.5% in Western countries and approximately 2.2% in Japan. It accounts for 50% of all dementias in Japan, 20% to 40% in Europe and 15% in Latin America. 25% of stroke patients develop new-onset dementia within one year of their stroke. One study found that in the United States, the prevalence of vascular dementia in all people over the age of 71 is 2.43%, and another found that the prevalence of the dementias doubles with every 5.1 years of age.[35][36] The incidence peaks between the fourth and the seventh decades of life and 80% of patients have a history of hypertension.

A recent meta-analysis identified 36 studies of prevalent stroke (1.9 million participants) and 12 studies of incident stroke (1.3 million participants).[9] For prevalent stroke, the pooled hazard ratio for all-cause dementia was 1.69 (95% confidence interval: 1.49–1.92; P < .00001; I2 = 87%). For incident stroke, the pooled risk ratio was 2.18 (95% confidence interval: 1.90–2.50; P < .00001; I2 = 88%). Study characteristics did not modify these associations, with the exception of sex, which explained 50.2% of between-study heterogeneity for prevalent stroke. These results confirm that stroke is a strong, independent, and potentially modifiable risk factor for all-cause dementia.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Multi-Infarct Dementia Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 Uwagbai, O; Kalish, VB (January 2020). "Vascular Dementia". PMID 28613567.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Cunningham EL, McGuinness B, Herron B, Passmore AP (May 2015). "Dementia". The Ulster Medical Journal. 84 (2): 79–87. PMC 4488926. PMID 26170481.

- ↑ Festa, Joanne; Lazar, Ronald (2009). Neurovascular Neuropsychology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-387-70715-0. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- ↑ Karantzoulis S, Galvin JE (November 2011). "Distinguishing Alzheimer's disease from other major forms of dementia". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (11): 1579–91. doi:10.1586/ern.11.155. PMC 3225285. PMID 22014137.

- ↑ Office of Communications and Public Liaison. "NINDS Multi-Infarct Dementia Information Page". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Human Brain - Dementia Associated with Depression. Oxford: Elsevier Science and Technology. 2002. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ↑ Love S (December 2005). "Neuropathological investigation of dementia: a guide for neurologists". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 76 Suppl 5 (supplement 5): v8-14. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.080754. PMC 1765714. PMID 16291923.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kuźma E, Lourida I, Moore SF, Levine DA, Ukoumunne OC, Llewellyn DJ (November 2018). "Stroke and dementia risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 14 (11): 1416–1426. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3061. PMC 6231970. PMID 30177276.

- ↑ Arvanitakis Z. "Dementia And Vascular Disease". Archived from the original on 2012-01-20.

- ↑ Vlassenko AG, Mintun MA, Xiong C, Sheline YI, Goate AM, Benzinger TL, Morris JC (November 2011). "Amyloid-beta plaque growth in cognitively normal adults: longitudinal [11C]Pittsburgh compound B data". Annals of Neurology. 70 (5): 857–61. doi:10.1002/ana.22608. PMC 3243969. PMID 22162065.

- ↑ Sojkova J, Zhou Y, An Y, Kraut MA, Ferrucci L, Wong DF, Resnick SM (May 2011). "Longitudinal patterns of β-amyloid deposition in nondemented older adults". Archives of Neurology. 68 (5): 644–9. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.77. PMC 3136195. PMID 21555640.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Makhlouf S, Messelmani M, Zaouali J, Mrissa R (2018). "Cognitive impairment in celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity: review of literature on the main cognitive impairments, the imaging and the effect of gluten free diet". Acta Neurol Belg (Review). 118 (1): 21–27. doi:10.1007/s13760-017-0870-z. PMID 29247390.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Zis P, Hadjivassiliou M (26 February 2019). "Treatment of Neurological Manifestations of Gluten Sensitivity and Coeliac Disease". Curr Treat Options Neurol (Review). 21 (3): 10. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0552-7. PMID 30806821.

- ↑ Wetterling T, Kanitz RD, Borgis KJ (January 1996). "Comparison of different diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia (ADDTC, DSM-IV, ICD-10, NINDS-AIREN)". Stroke. 27 (1): 30–6. doi:10.1161/01.str.27.1.30. PMID 8553399.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Tang WK, Chan SS, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, Wong KS, Kwok TC, Mok V, Wong KT, Richards PS, Ahuja AT (2004). "Impact of applying NINDS-AIREN criteria of probable vascular dementia to clinical and radiological characteristics of a stroke cohort with dementia". Cerebrovascular Diseases. 18 (2): 98–103. doi:10.1159/000079256. PMID 15218273.

- ↑ Pantoni L, Inzitari D (October 1993). "Hachinski's ischemic score and the diagnosis of vascular dementia: a review". Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 14 (7): 539–46. doi:10.1007/BF02339212. PMID 8282525.

- ↑ Bonte FJ, Harris TS, Hynan LS, Bigio EH, White CL. Tc-99m HMPAO SPECT in the Differential Diagnosis of the Dementias with Histopathologic Confirmation. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. July 2006;31(7):376–378. doi:10.1097/01.rlu.0000222736.81365.63. PMID 16785801.

- ↑ Dougall NJ, Bruggink S, Ebmeier KP. Systematic Review of the Diagnostic Accuracy of 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT in Dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12(6):554–570. doi:10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.6.554. PMID 15545324.

- ↑ Waldemar G.. Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Management of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Disorders Associated with Dementia: EFNS guideline. European Journal of Neurology. January 2007;14(1):e1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x. PMID 17222085.

- ↑ From NINCDS-ADRDA Alzheimer's Criteria: Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O'brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P (August 2007). "Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria". The Lancet. Neurology. 6 (8): 734–46. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. PMID 17616482.

- ↑ McVeigh, Catherine; Passmore, Peter (Sep 2006). "Vascular dementia: prevention and treatment". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 1 (3): 229–235. doi:10.2147/ciia.2006.1.3.229. ISSN 1176-9092. PMC 2695177. PMID 18046875.

- ↑ Erkinjuntti, Timo (Feb 2012). Gelder, Michael; Andreasen, Nancy; Lopez-Ibor, Juan; Geddes, John (eds.). New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780199696758.001.0001. ISBN 9780199696758. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Baskys A, Cheng JX (November 2012). "Pharmacological prevention and treatment of vascular dementia: approaches and perspectives". Experimental Gerontology. 47 (11): 887–91. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2012.07.002. PMID 22796225.

- ↑ Mijajlović MD, Pavlović A, Brainin M, Heiss WD, Quinn TJ, Ihle-Hansen HB, et al. (January 2017). "Post-stroke dementia - a comprehensive review". BMC Medicine. 15 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0779-7. PMC 5241961. PMID 28095900.

- ↑ Rands, Gianetta; Orrell, Martin (23 October 2000). "Aspirin for vascular dementia" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001296. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ J, Birks; B, McGuinness; D, Craig (2013-05-31). "Rivastigmine for Vascular Cognitive Impairment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. PMID 23728651. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 van de Vorst IE, Vaartjes I, Geerlings MI, Bots ML, Koek HL (October 2015). "Prognosis of patients with dementia: results from a prospective nationwide registry linkage study in the Netherlands". BMJ Open. 5 (10): e008897. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008897. PMC 4636675. PMID 26510729.

- ↑ Guehne U, Riedel-Heller S, Angermeyer MC (2005). "Mortality in dementia". Neuroepidemiology. 25 (3): 153–62. doi:10.1159/000086680. PMID 15990446.

- ↑ Bruandet A, Richard F, Bombois S, Maurage CA, Deramecourt V, Lebert F, Amouyel P, Pasquier F (February 2009). "Alzheimer disease with cerebrovascular disease and vascular dementia: clinical features and course compared with Alzheimer disease". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 80 (2): 133–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.137851. PMID 18977819.

- ↑ Villarejo A, Benito-León J, Trincado R, Posada IJ, Puertas-Martín V, Boix R, Medrano MR, Bermejo-Pareja F (2011). "Dementia-associated mortality at thirteen years in the NEDICES Cohort Study". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 26 (3): 543–51. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110443. PMID 21694455.

- ↑ Garcia-Ptacek S, Farahmand B, Kåreholt I, Religa D, Cuadrado ML, Eriksdotter M (2014). "Mortality risk after dementia diagnosis by dementia type and underlying factors: a cohort of 15,209 patients based on the Swedish Dementia Registry". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 41 (2): 467–77. doi:10.3233/JAD-131856. PMID 24625796.

- ↑ Battistin L, Cagnin A (December 2010). "Vascular cognitive disorder. A biological and clinical overview". Neurochemical Research. 35 (12): 1933–8. doi:10.1007/s11064-010-0346-5. PMID 21127967.

- ↑ "Vascular Dementia: A Resource List". Archived from the original on 2015-10-05. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, Burke JR, Hurd MD, Potter GG, Rodgers WL, Steffens DC, Willis RJ, Wallace RB (2007). "Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study". Neuroepidemiology. 29 (1–2): 125–32. doi:10.1159/000109998. PMC 2705925. PMID 17975326.

- ↑ Jorm AF, Korten AE, Henderson AS (November 1987). "The prevalence of dementia: a quantitative integration of the literature". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 76 (5): 465–79. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02906.x. PMID 3324647.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 maint: url-status

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2017

- Cognitive disorders

- Dementia

- Learning disabilities

- Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders

- Psychiatric diagnosis

- RTT