Mortality displacement

In epidemiology, mortality displacement is the occurrence of deaths at an earlier time than they would have otherwise occurred, meaning the deaths are displaced from the future into the present. The displacement may be described as the result of events such as heat waves, cold spells, epidemics and pandemics (especially influenza pandemics), famine or war, and allows for estimates of the mortality caused by those events.

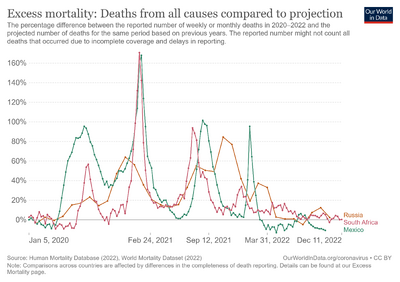

The earlier deaths are called excess deaths (i.e., more deaths than expected), and this time period is followed by a period of mortality deficit (i.e., fewer deaths than expected, because those people have died at a younger age). It is also known as "harvesting". Mortality deficit in a particular time period can be caused by deaths displaced to an earlier time (due to harvesting by an event in the past) or deaths displaced to a future time (due to lives being saved, also called "avoided mortality").[1][2]

Measurement

Different institutions and initiatives offer weekly data to monitor excess mortality. Significant efforts to capture short term mortality data have been made along 2020 due to the pandemic of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its worldwide effects. Eurostat launched in April 2020 a collection of weekly death data that provide for most of the EU countries weekly death data series by 5-year age groups and sex in NUTS3 regions within the countries starting from the year 2000.[3] This temporary data collection was established in order to support the policy and research efforts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data are transmitted by the National Statistical Institutes on voluntary basis and it is being updated, depending on the country, weekly.[4]

In May 2020, the Human Mortality Database project launched a new data series, the Short-term Mortality Fluctuation series (STMF), offering freely available weekly death counts by age and sex for a growing number of countries (34 in October 2020), as well as a visualization tool that captures the excess mortality on a weekly basis. The STMF was established to provide data for scientific analysis of all-cause mortality fluctuations by week within each calendar year in standard formats. Part of the Human Mortality Database use a joint project of two teams based in the Laboratory of Demographic Data Archived 2022-12-13 at the Wayback Machine at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) and at the Department of Demography Archived 2022-10-06 at the Wayback Machine of the University of California, Berkeley (UCB).

The collaborative network EuroMOMO (European mortality monitoring activity), monitors mortality across 24 European countries in order to detect and measure excess deaths related to seasonal influenza, pandemics, and other public health threats. EuroMOMO is hosted and maintained by the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention of Copenhagen, Denmark. They offer regular reports (weekly bulletins), graphs and maps showing the present levels of mortality but the network does not publish openly data. Individual partners may decide to share openly some selected national data, like for instance, MoMo-Spain Archived 2022-04-23 at the Wayback Machine. The study centre at the Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen publishes a weekly situation report and regular scientific articles. Periods of high excess mortality have also been described for the United States.[5]

Heat waves

During heat waves, for instance, there are often additional deaths observed in the population, affecting especially older adults and those who are sick. After some periods with excess mortality, however, there has also been observed a decrease in overall mortality during the subsequent weeks. Such short-term forward shift in mortality rate is also referred to as harvesting effect. The subsequent, compensatory reduction in mortality suggests that the heat wave especially affected those whose health was already so compromised that they "would have died in the short-term anyway" due to other causes, meaning that not all the deaths caused by the heat wave could have been avoided by addressing the effects of heat waves.[6]

References

- ↑ Islam, Nazrul; Shkolnikov, Vladimir M; Acosta, Rolando J; Klimkin, Ilya; Kawachi, Ichiro; Irizarry, Rafael A; Alicandro, Gianfranco; Khunti, Kamlesh; Yates, Tom; Jdanov, Dmitri A; White, Martin (2021). "Excess deaths associated with covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries". BMJ. 373: n1137. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1137. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 8132017. PMID 34011491.

- ↑ Beaney, Thomas; Clarke, Jonathan M; Jain, Vageesh; Golestaneh, Amelia Kataria; Lyons, Gemma; Salman, David; Majeed, Azeem (2020). "Excess mortality: the gold standard in measuring the impact of COVID-19 worldwide?". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 113 (9): 329–334. doi:10.1177/0141076820956802. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 7488823. PMID 32910871.

- ↑ "Weekly deaths – special data collection". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Archived from the original on 2019-07-24. Retrieved 2022-11-15.

- ↑ "Weekly deaths – special data collection (demomwk)". Eurostat. 2020. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ↑ Dushoff, Jonathan; Plotkin, Joshua B.; Viboud, Cecile; Earn, David J. D.; Simonsen, Lone (2006-01-15). "Mortality due to Influenza in the United States – An Annualized Regression Approach Using Multiple-Cause Mortality Data". American Journal of Epidemiology. 163 (2): 181–187. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj024. ISSN 0002-9262. PMID 16319291. Archived from the original on 2022-10-27. Retrieved 2022-11-15.

- ↑ Huynen, M.M.; Martens, P.; Schram, D.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Kunst, A.E. (May 2001). "The Impact of Heat Waves and Cold Spells on Mortality Rates in the Dutch Population". Environmental Health Perspectives. Vol. 109, no. 5. pp. 463–470. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109463. PMC 1240305. PMID 11401757.

External links

- Human Mortality Database Archived 2021-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, Short-term Mortality Fluctuation data series

- EuroMOMO Homepage Archived 2020-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- CDC (US Center for Disease Control) Homepage Archived 2020-06-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Excess mortality during the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) Archived 2022-11-15 at the Wayback Machine – Our World in Data