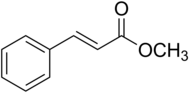

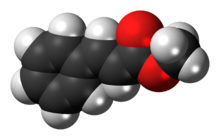

Methyl cinnamate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Methyl (2E)-3-phenylprop-2-enoate | |

| Other names

Methyl cinnamate

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.813 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H10O2 | |

| Molar mass | 162.188 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.092 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 34–38 °C (93–100 °F; 307–311 K) |

| Boiling point | 261–262 °C (502–504 °F; 534–535 K) |

| Insoluble | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling:[3] | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H317 | |

| P261, P272, P280, P302+P352, P321, P333+P313, P363, P501 | |

| Flash point | > 110 °C (230 °F; 383 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Methyl cinnamate is the methyl ester of cinnamic acid and is a white or transparent solid with a strong, aromatic odor. It is found naturally in a variety of plants, including in fruits, like strawberry, and some culinary spices, such as Sichuan pepper and some varieties of basil.[4] Eucalyptus olida has the highest known concentrations of methyl cinnamate (98%) with a 2–6% fresh weight yield in the leaf and twigs.[5]

Methyl cinnamate is used in the flavor and perfume industries. The flavor is fruity and strawberry-like; and the odor is sweet, balsamic with fruity odor, reminiscent of cinnamon and strawberry.[1]

It is known to attract males of various orchid bees, such as Aglae caerulea.[6]

List of plants that contain the chemical

- Eucalyptus olida 'Strawberry Gum'

- Ocotea quixos South American (Ecuadorian) Cinnamon, Ishpingo[7]

- Ocimum americanum cv. Purple Lovingly (Querendona Morada)

- Ocimum americanum cv. Purple Castle (Castilla Morada)

- Ocimum americanum cv. Purple Long-legged (Zancona morada)

- Ocimum americanum cv. Clove (Clavo)

- Ocimum basilicum cv. Sweet Castle (Dulce de Castilla)

- Ocimum basilicum cv. White Compact (Blanca compacta)

- Ocimum basilicum cv. large green leaves (verde des horjas grandes)

- Ocimum micranthum cv. Cinnamon (Canela)

- Ocimum minimum cv. Little Virgin (Virgen pequena)

- Ocimum minimum cv. Purple Virgin (Virgen morada)

- Ocimum sp. cv. Purple ruffle (Crespa morada)

- Ocimum sp. cv. White Ruffle (Crespa blanca)

- Stanhopea embreei, an orchid

- Vanilla

Toxicology and safety

Moderately toxic by ingestion. The oral LD50 for rats is 2610 mg/kg.[8] It is combustible as a liquid, and when heated to decomposition it emits acrid smoke and irritating fumes.

Compendial status

See also

- Eucalyptus oil

- Ralf Sieckmann v Deutsches Patent und Markenamt, a court case concerning a company attempting to trademark the chemical compound.

References

- ^ a b Methyl cinnamate, at goodscents.com

- ^ Methyl cinnamate, at Sigma-Aldrich

- ^ "Methyl cinnamate". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Viña, Amparo; Murillo, Elizabeth (2003). "Essential oil composition from twelve varieties of basil (Ocimum spp) grown in Colombia". Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society. 14 (5): 744–9. doi:10.1590/S0103-50532003000500008.

- ^ Boland DJ, Brophy JJ, House APN (1991). Eucalyptus Leaf Oils. ISBN 978-0-909605-69-8.

- ^ Williams, N.H.; Whitten, W.M. (1983). "Orchid floral fragrances and male euglossine bees: methods and advances in the last sesquidecade". Biol. Bull. 164 (3): 355–395. doi:10.2307/1541248. JSTOR 1541248.

- ^ Bruni, Renato; Medici, Alessandro; Andreotti, Elisa; Fantin, Carlo; Muzzoli, Mariavittoria; Dehesa, Marco; Romagnoli, Carlo; Sacchetti, Gianni (2004). "Chemical composition and biological activities of Ishpingo essential oil, a traditional Ecuadorian spice from Ocotea quixos (Lam.) Kosterm. (Lauraceae) flower calices". Food Chemistry. 85 (3): 415–21. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.07.019. hdl:11381/1449234.

- ^ Richard J. Lewis (1989). Food Additives Handbook. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 304–. ISBN 978-0-442-20508-9.

- ^ Therapeutic Goods Administration (1999). "Approved Terminology for Medicines" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2006. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Articles with changed InChI identifier

- Chembox having GHS data

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Chembox image size set

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Spanish-language text

- Cinnamate esters

- Methyl esters

- Flavors

- Sweet-smelling chemicals