Shin splints

| Shin splints | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS),[1] soleus syndrome,[2] tibial stress syndrome,[2] periostitis[2] | |

| |

| Red area represents the tibia. Pain is generally in the inner and lower 2/3rds of tibia. | |

| Specialty | Sports medicine |

| Symptoms | Pain along the inside edge of the shinbone[1] |

| Complications | Stress fracture[2] |

| Risk factors | Runners, dancers, military personnel[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Stress fracture, tendinitis, exertional compartment syndrome[1] |

| Treatment | Rest with gradual return to exercise[1][2] |

| Prognosis | Good[2] |

| Frequency | 4 to 35% (at risk groups)[2] |

A shin splint is pain along the inside edge of the shinbone (tibia) due to inflammation of tissue in the area.[1] Generally this is between the middle of the lower leg to the ankle.[2] The pain may be dull or sharp and is generally brought on by exercise.[1] It generally resolves during periods of rest.[3] Complications may include stress fractures.[2]

Shin splints typically occur due to excessive physical activity.[1] Groups that are commonly affected include runners, dancers, and military personnel.[2] The underlying mechanism is not entirely clear.[2] Diagnosis is generally based on the symptoms, with medical imaging done to rule out other possible causes.[2]

Shin splints are generally treated by rest followed by a gradual return to exercise.[1][2][3] Other measures such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cold packs, physical therapy, and compression may be used.[1][2] Shoe insoles may help some people.[1] Surgery is rarely required, but may be done if other measures are not effective.[2] Rates of shin splints in at-risk groups range from 4% to 35%.[2] The condition occurs more often in women.[2] It was first described in 1958.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Shin splint pain is described as a recurring dull ache, sometimes becoming an intense pain, along the inner part of the lower two-thirds of the tibia.[4] The pain increases during exercise, and some individuals experience swelling in the pain area.[5] In contrast, stress fracture pain is localized to the fracture site.[6]

Women are several times more likely to progress to stress fractures from shin splints.[7][8][9] This is due in part to women having a higher incidence of diminished bone density and osteoporosis.[citation needed]

Causes

Shin splints typically occur due to excessive physical activity.[1] Groups that are commonly affected include runners, dancers, and military personnel.[2]

Risk factors for developing shin splints include:

- Flat feet or rigid arches[1]

- Being overweight[3]

- Excessively tight calf muscles (which can cause excessive pronation)[10]

- Engaging the medial shin muscle in excessive amounts of eccentric muscle activity[7]

- Undertaking high-impact exercises on hard, noncompliant surfaces (such as running on asphalt or concrete)[7]

People who have previously had shin splints are more likely to have them again.[11]

Pathophysiology

While the exact mechanism is unknown, shin splints can be attributed to the overloading of the lower leg due to biomechanical irregularities resulting in an increase in stress exerted on the tibia. A sudden increase in intensity or frequency in activity level fatigues muscles too quickly to help shock absorption properly, forcing the tibia to absorb most of the impact. This stress is associated with the onset of shin splints.[12] Muscle imbalance, including weak core muscles, inflexibility and tightness of lower leg muscles, including the gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantar muscles (commonly the flexor digitorum longus) can increase the possibility of shin splints.[13] The pain associated with shin splints is caused from a disruption of Sharpey's fibres that connect the medial soleus fascia through the periosteum of the tibia where it inserts into the bone.[12] With repetitive stress, the impact forces eccentrically fatigue the soleus and create repeated tibial bending or bowing, contributing to shin splints. The impact is made worse by running uphill, downhill, on uneven terrain, or on hard surfaces. Improper footwear, including worn-out shoes, can also contribute to shin splints.[14][15]

Diagnosis

Shin splints are generally diagnosed from a history and physical examination.[3] The important factors on history are the location of pain, what triggers the pain, and the absence of cramping or numbness.[3]

On physical examination, gentle pressure over the tibia will recreate the type of pain experienced.[11][16] Generally more than a 5 cm length of tibia is involved.[11] Swelling, redness, or poor pulses in addition to the symptoms of shin splints indicate a different underlying cause.[3]

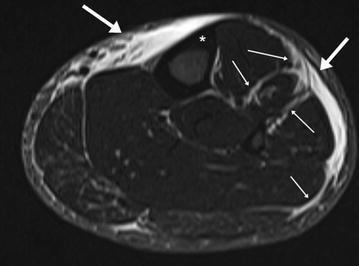

-

MRI of the left lower leg-severe “shin-splint”

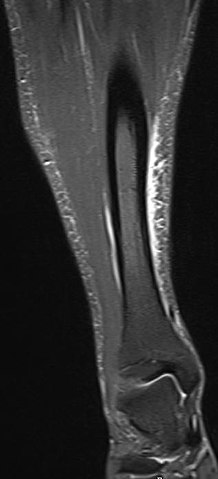

-

Magnetic resonance image of the lower leg in the coronal plane showing high signal (bright) areas around the tibia as signs of shin splints.

Differential diagnosis

Other potential causes include stress fractures, compartment syndrome, nerve entrapment, and popliteal artery entrapment syndrome.[16] If the cause is unclear, medical imaging such as a bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be performed.[3] Bone scans and MRI can differentiate between stress fractures and shin splints.[11]

Treatment

Treatments include rest, ice, and gradually returning to activity.[13] Rest and ice help the tibia to recover from sudden, high levels of stress and reduce inflammation and pain levels. It is important to reduce significantly any pain or swelling before returning to activity. Strengthening exercises should be performed after pain has subsided, on calves, quadriceps and gluteals.[13] Cross training (e.g., cycling, swimming, boxing) is recommended in order to maintain aerobic fitness.[17] Individuals should return to activity gradually, beginning with a short and low intensity level. Over multiple weeks, they can slowly work up to normal activity level. It is important to decrease activity level if any pain returns. Individuals should consider running on other surfaces besides asphalt, such as grass, to decrease the amount of force the lower leg must absorb.[7]

Orthoses and insoles help to offset biomechanical irregularities, like pronation, and help to support the arch of the foot.[18] Other conservative interventions include improving form during exercise, footwear refitting, orthotics, manual therapy, balance training (e.g., using a balance board), cortisone injections, and calcium and vitamin D supplementation.[13]

Less-common forms of treatment for more-severe cases of shin splints include extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) and surgery.[19] Surgery is only performed in extreme cases where more-conservative options have been tried for at least a year.[20] However, surgery does not guarantee 100% recovery.

Epidemiology

Rates of shin splints in at-risk groups are 4% to 35%.[2] Women are affected more often than men.[21]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Shin Splints - OrthoInfo - AAOS". www.orthoinfo.org. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 Reshef, N; Guelich, DR (April 2012). "Medial tibial stress syndrome". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 31 (2): 273–90. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.09.008. PMID 22341017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 McClure, CJ; Oh, R (January 2019). "Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome". PMID 30860714.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Carr, K.; Sevetson, E.; Aukerman, D. (2008). "Clinical inquiries. How can you help athletes prevent and treat shin splints?". The Journal of Family Practice. 57 (6): 406–408. PMID 18544325.

- ↑ Tweed, J.L.; Avil, S.J.; Campbell, J.A.; Barnes, M.R. (2008). "Etiologic factors in the development of medial tibial stress syndrome: A review of the literature". Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 98 (2): 107–111. doi:10.7547/0980436. PMID 18347118.

- ↑ Edwards, Peter H.; Wright, Michelle L.; Hartman, Jodi F. (2005). "A Practical Approach for the Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Leg Pain in the Athlete". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 33 (8): 1241–1249. doi:10.1177/0363546505278305. PMID 16061959. S2CID 7828716.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Yates, B.; White, S. (2004). "The incidence and risk factors in the development of medial tibial stress syndrome among naval recruits". American Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (3): 772–780. doi:10.1177/0095399703258776. PMID 15090396. S2CID 24603853.

- ↑ Bennett, Jason E.; Reinking, Mark F.; Pluemer, Bridget; Pentel, Adam; Seaton, Marcus; Killian, Clyde (2001). "Factors Contributing to the Development of Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome in High School Runners". Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 31 (9): 504–510. doi:10.2519/jospt.2001.31.9.504. PMID 11570734.

- ↑ Haycock, C.E. (1976). "Susceptibility of women athletes to injury. Myths vs reality". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 236 (2): 163–165. doi:10.1001/jama.236.2.163. PMID 947011.

- ↑ Brukner, Peter (2000). "Exercise-related lower leg pain: An overview". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 32 (3 Suppl): S1–S3. doi:10.1249/00005768-200003001-00001. PMID 10730988.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Moen, MH; Tol, JL; Weir, A; Steunebrink, M; De Winter, TC (2009). "Medial tibial stress syndrome: a critical review". Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 39 (7): 523–46. doi:10.2165/00007256-200939070-00002. PMID 19530750. S2CID 40720414.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Craig, Debbie I. (2008). "Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Evidence-Based Prevention". Journal of Athletic Training. 43 (3): 316–318. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-43.3.316. PMC 2386425. PMID 18523568.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Galbraith, R. Michael; Lavallee, Mark E. (2009-10-07). "Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2 (3): 127–133. doi:10.1007/s12178-009-9055-6. ISSN 1935-973X. PMC 2848339. PMID 19809896.

- ↑ Lobby, Mackenzie (9 September 2014). "Running 101: How To Select The Best Pair Of Running Shoes". Competitor.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ "Shin Splints Symptoms, Treatment, Recovery, and Prevention". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Patel, Deepak S.; Roth, Matt; Kapil, Neha (2011). "Stress fractures: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention" (PDF). American Family Physician. 83 (1): 39–46. PMID 21888126. S2CID 1736230. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-02-28. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ↑ Couture, Christopher (2002). "Tibial Stress Injuries: Decisive Diagnosis and Treatment of 'Shin Splints'". The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 30 (6): 29–36. doi:10.3810/psm.2002.06.337. PMID 20086529. S2CID 39133382.

- ↑ Loudon, Janice K.; Dolphino, Martin R. (2010). "Use of Foot Orthoses and Calf Stretching for Individuals with Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome". Foot & Ankle Specialist. 3 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1177/1938640009355659. PMID 20400435. S2CID 3374384.

- ↑ Rompe, Jan D.; Cacchio, Angelo; Furia, John P.; Maffulli, Nicola (2010). "Low-Energy Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy as a Treatment for Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 38 (1): 125–132. doi:10.1177/0363546509343804. PMID 19776340. S2CID 21114701.

- ↑ Yates, Ben; Allen, Mike J.; Barnes, Mike R. (2003). "Outcome of Surgical Treatment of Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 85 (10): 1974–1980. doi:10.2106/00004623-200310000-00017. PMID 14563807.

- ↑ Newman, Phil; Witchalls, Jeremy; Waddington, Gordon; Adams, Roger (2013). "Risk factors associated with medial tibial stress syndrome in runners: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 4: 229–241. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S39331. ISSN 1179-1543. PMC 3873798. PMID 24379729.

External links

| Classification |

|---|