Mallory–Weiss syndrome

| Mallory–Weiss syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Gastro-esophageal laceration syndrome | |

| |

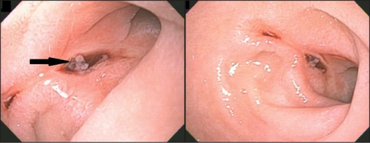

| Mallory–Weiss tear affecting the esophageal side of the gastroesophageal junction | |

Mallory–Weiss syndrome or gastro-esophageal laceration syndrome refers to bleeding from a laceration in the mucosa at the junction of the stomach and esophagus.[1] This is usually caused by severe vomiting because of alcoholism or bulimia,[2] but can be caused by any condition which causes violent vomiting and retching such as food poisoning. The syndrome presents with hematemesis. The laceration is sometimes referred to as a Mallory–Weiss tear.

Signs and symptoms

Mallory–Weiss Syndrome often presents as an episode of vomiting up blood (hematemesis) after violent retching or vomiting, but may also be noticed as old blood in the stool (melena), and a history of retching may be absent.

In most cases, the bleeding stops spontaneously after 24–48 hours, but endoscopic or surgical treatment is sometimes required. The condition is rarely fatal.[citation needed]

Causes

It is often associated with alcoholism[3] and eating disorders and there is some evidence that presence of a hiatal hernia is a predisposing condition. Forceful vomiting causes tearing of the mucosa at the junction. NSAID abuse is also a rare association.[4] In rare instances some chronic disorders like Ménière's disease that cause long term nausea and vomiting could be a factor.

The tear involves the mucosa and submucosa but not the muscular layer (contrast to Boerhaave syndrome which involves all the layers).[5] Most patients are between the ages of 30 and 50 years, although it has been reported in infants aged as young as 3 weeks, as well as in older people [6][7] Hyperemesis gravidarum, which is severe morning sickness associated with vomiting and retching in pregnancy, is also a known cause of Mallory–Weiss tear.[8]

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis is by endoscopy.[9] Proper history taking by the medical doctor to distinguish other conditions that cause haematemesis but definitive diagnosis is by conducting esophagogastroduodenoscopy.[10][11][12]

Treatment

Treatment is usually supportive as persistent bleeding is uncommon. However cauterization or injection of epinephrine[13] to stop the bleeding may be undertaken during the index endoscopy procedure. Very rarely embolization of the arteries supplying the region may be required to stop the bleeding. If all other methods fail, high gastrostomy can be used to ligate the bleeding vessel. A Blakemore tube will not be able to stop bleeding as here the bleeding is arterial and the pressure in the balloon is not sufficient to overcome the arterial pressure.

History

The condition was first described in 1929 by G. Kenneth Mallory and Soma Weiss in 15 alcoholic patients.[14]

See also

- Boerhaave syndrome – Full thickness esophageal ruptures are also often secondary to vomiting/retching.

- Hematemesis

References

- ↑ "Mallory-Weiss Syndrome (Mallory-Weiss Tear)". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ Sattar, Husain A. (2011). Fundamentals of Pathology. Pathoma, LLC. ISBN 9780983224600.

- ↑ Caroli A, Follador R, Gobbi V, Breda P, Ricci G (1989). "[Mallory–Weiss syndrome. Personal experience and review of the literature]". Minerva Dietologica e Gastroenterologica (in italiano). 35 (1): 7–12. PMID 2657497.

- ↑ R, Eslava García; Jl, Negrete Pardo; P, Muñoz Kim; S, García (April 1990). "[Mallory–Weiss Syndrome. Surgical Treatment After Sclerotherapy. Presentation of a Case and Review of the Literature]". Revista de Gastroenterologia de Mexico. 55 (2): 75–7. PMID 2287873.

- ↑ Boerhaave Syndrome at eMedicine

- ↑ Ba¸k-Romaniszyn, L.; Małecka-Panas, E.; Czkwianianc, E.; Płaneta-Małecka, I. (1999-03-01). "Mallory–Weiss syndrome in children". Diseases of the Esophagus. 12 (1): 65–67. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2050.1999.00006.x. ISSN 1120-8694. PMID 10941865. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- ↑ Kitagawa, Takashi; Takano, Hideya; Sohma, Mitsuhiro; Mutoh, Eiji; Takeda, Shouzo (1994). "Clinical Study of Mallory–Weiss Syndrome in the Aged Patients Over 75 Year. Mainly Five Cases Induced by the Endoscopic Examination". Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. Japanese Journal of Geriatrics. 31 (5): 374–379. doi:10.3143/geriatrics.31.374. ISSN 0300-9173. PMID 8072208.

- ↑ Parva M, Finnegan M, Keiter C, Mercogliano G, Perez CM (August 2009). "Mallory–Weiss tear diagnosed in the immediate postpartum period: a case report". J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 31 (8): 740–3. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34280-3. PMID 19772708.

- ↑ Hastings, Paul R.; Peters, Kenneth W.; Cohn, Isidore (November 1981). "Mallory–Weiss syndrome". The American Journal of Surgery. 142 (5): 560–562. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(81)90425-6. PMID 7304810.

- ↑ "Gastroscopy – examination of oesophagus and stomach by endoscope". BUPA. December 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (November 2004). "Upper Endoscopy". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ "What is Upper GI Endoscopy?". Patient Center -- Procedures. American Gastroenterological Association. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ Gawrieh S, Shaker R (2005). "Treatment of actively bleeding Mallory–Weiss syndrome: epinephrine injection or band ligation?". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 7 (3): 175. doi:10.1007/s11894-005-0030-0. PMID 15913474. S2CID 195343875.

- ↑ Weiss S, Mallory GK (1932). "Lesions of the cardiac orifice of the stomach produced by vomiting". Journal of the American Medical Association. 98 (16): 1353–5. doi:10.1001/jama.1932.02730420011005.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |