Loa loa

| Loa loa | |

|---|---|

| |

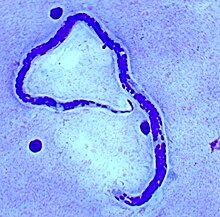

| Loa loa microfilaria found in blood film. (Giemsa stain) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Chromadorea |

| Order: | Rhabditida |

| Family: | Onchocercidae |

| Genus: | Loa |

| Species: | L. loa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Loa loa (Cobbold, 1864)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dracunculus loa Cobbold, 1864[1] Filaria loa (Cobbold, 1864) | |

Loa loa is a filarial (arthropod-borne) nematode (roundworm) that causes Loa loa filariasis. Loa loa actually means "worm worm", but is commonly known as the "eye worm", as it localizes to the conjunctiva of the eye. Loa loa is commonly found in Africa.[2] It mainly inhabits rain forests in West Africa and has native origins in Ethiopia.[3] The disease caused by Loa loa is called loiasis and is one of the neglected tropical diseases.[4]

L. loa is one of three parasitic filarial nematodes that cause subcutaneous filariasis in humans. The other two are Mansonella streptocerca and Onchocerca volvulus (causes river blindness).

Maturing larvae and adults of the "eye worm" occupy the subcutaneous layer of the skin – the fat layer – of humans, causing disease. The L. loa adult worm which travels under the skin can survive up to 10–15 years, causing inflammations known as Calabar swellings. The adult worm travels under the skin, where the female deposits the microfilariae which can develop in the host’s blood within 5 to 6 months and can survive up to 17 years. The young larvae, or microfilariae, develop in horseflies of the genus Chrysops (deer flies, yellow flies), including the species C. dimidiata and C. silacea, which infect humans by biting them. After bites from these infected flies, the microfilariae are unique in that they travel in the peripheral blood during the day and migrate into the lungs at night.[5]

Morphology

L. loa worms have a simple structure consisting of a head (which lacks lips), a body, and a blunt tail. The outer body of the worm is composed of a cuticle with 3 main layers made up of collagen and other compounds which aid in protecting the nematodes while they are inside the digestive system of their host. Juveniles have a similar appearance to adult worms, but are significantly smaller.[6] Male adults range from 20 to 34 mm long and 350 to 430 μm wide. Female adults range from 20 to 70 mm long and can be about 425 μm wide. They vary in color.[2]

Lifecycle

-

Loa loa is the filarial nematode species that causes loa loa filariasis

-

Whole blood with microfilaria worm, giemsa stain

The human is the definitive host, in which the parasitic worms attain sexual maturity, mate, and produce microfilariae. The flies serve as intermediate hosts in which the microfilariae undergo part of their morphological development, and then are borne to the next definitive host.[7]

Two species of Chrysops deerflies, C. silacea and C. dimidiata, are the main vectors for this filariasis.[8]

- A fly bearing third-stage filarial larvae in its proboscis infects the human host through the bite wound.

- After entering the human host, the larvae mature into adults, commonly in subcutaneous tissue. Adult females measure about 40 to 70 mm in length and 0.5 mm in diameter. Males measure some 30 to 34 mm by 0.35 to 0.43 mm.

- The adult female produces large numbers of microfilariae, about 250 to 300 μm in length and 6-8 μm in width. She continues to do so continuously for her lifetime, which typically spans several years.

- Microfilariae tend to reside within spinal fluids, urine, and sputum; by day, they also circulate in the bloodstream. Apart from their presence in bodily fluids, however, microfilariae in the noncirculating phase also occur in the lungs.

- The vector fly ingests microfilariae while feeding on the host's blood.

- Once inside the vector, the microfilaria sheds its sheaths and escapes through the walls of the midgut into the fly’s haemocoel.

- It then migrates through the hemolymph into the wing muscles in the fly's thorax.

- In the thoracic muscles, the microfilaria develops successively into a first-stage larva, second-stage larva, and finally into the infectious third-stage larva.

- The third-stage larva migrates to the fly’s proboscis.

- Once the larva is established in the proboscis and the fly takes its next human blood meal, the cycle of infection continues.

Disease

Signs and symptoms

Usually, about five months are needed for larvae (transferred from a fly) to mature into adult worms, which they can only do inside the human body. The most common display of infection is the localized allergic inflammations called Calabar or Cameroon swellings that signify the migration of the adult worm in the tissues away from the injection site by the vector. The migration does not cause significant damage to the host and is referred to as benign. However, these swellings can be painful, as they are mostly found near the joints.[9]

Although most infections with L. loa are asymptomatic, symptoms generally do not appear until years, or even more than a decade, after the bite from an infected fly. However, symptoms can appear as early as four months after a bite.[10] These parasites have a diurnal periodicity in which they circulate in the peripheral blood during the daytime, but migrate to vascular parts of the lungs during the night, where they are considered non circulatory. Therefore, the appearing and disappearing characteristics of this parasite can cause recurrent swelling that can cause painful enlargements of cysts in the connective tissue surrounding tendons. Additionally, chronic abscesses can be caused by the dying worms.[5]

The most visual sign of an adult worm infections is when the worm crosses the sclera of the eye, which causes significant pain to the host and is usually associated with inflammation and less likely, blindness. Eye worms typically cause little eye damage and last a few hours to a week.[9] Other tissues in which this worm can be found includes: the penis, testes, nipples, bridge of the nose, kidneys, and heart. The worms in these locations are not always externally visible.[11]

Risk factors

People at the highest risk for acquiring loiasis are those who live in the rainforests of West or Central Africa. Furthermore, the probability of getting bitten by a deerfly increases during the day and during rainy seasons. The flies are also attracted to smoke from wood fires. These flies do not commonly enter houses, but they are attracted to the houses that are well lit, so will congregate outside.[9]

Travelers can be infected in less than 30 days after arriving in an affected area, although they are more likely to be infected whilst being bitten by multiple deerflies over the course of many months. Men are more susceptible than women due to their increased exposure to the vectors during activities such as farming, hunting, and fishing.[12]

Diagnosis

The main methods of diagnosis include the presence of microfilariae in the blood, the presence of a worm in the eye, and the presence of skin swellings. However, in cases where none of those is the case, a blood count can be done. Patients with infections have a higher number of blood cells, namely eosinophils, as well as high IgE levels that indicate an active infection with helminth parasites. Due to the migration of microfilariae during the day, the accuracy of a blood test can be increased when samples are taken between 10 am and 2 pm.[11] A Giemsa stain is the most commonly used diagnostic test that uses a thick blood smear to count the microfilariae. Other than blood, microfilariae can also be observed in urine and saliva samples.[12]

Prevention

Currently, no control programs or vaccines for loiasis are available. However, diethylcarbamazine treatment is suggested to the reduce risk of infection. Avoiding areas where the vectors, deerflies, are found also reduces risk. This includes swamps, bogs, and shaded areas near rivers or near wood fires. Fly bites can be reduced by using insect repellents such as DEET and wearing long sleeves and pants during the daytime. Permethrin treatment on clothes is an additional repellent that could be used. Also, using malaria nets can reduce the number of fly bites acquired.[9]

Treatment

Adult worms found in the eye can be surgically removed with forceps after being paralyzed with a topical anesthesia. The worm is not paralyzed completely, so if it is not extracted quickly, it can vanish upon attempting extraction.[12]

Ivermectin has become the most common antiparasitic agent used worldwide, but can lead to residual microfilarial load when given in the management of loiasis. Treatment with ivermectin has shown to produce severe adverse neurological consequences in some cases. These treatment complications can be increased in individuals co-infected with onchocerciasis.[11] Some of these patients experienced cases of coma and resultant encephalopathy, parkinsonism, and death. After about 12 hours, the first signs start to appear and include fatigue, pain in joints, mutism, and incontinence. Severe disorders of the consciousness start to develop after about a day.[13]

Although Ivermectin is a common treatment for loiasis, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends treatment with diethylcarbamazine (DEC). Symptoms may be resolved with as little as 1–2 courses of DEC. DEC is chosen over Ivermectin because evidence supports its ability to kill both the adult worms and the microfilariae, which are the main cause of the severe neurological problems mentioned above. In some cases, albendazole may also be an effective treatment used to reduce the microfilariae prior to treatment with DEC. The body's response to albendazole is slow, so the patient being treated must be monitored closely and frequently to ensure it is effective.[14]

Epidemiology

Reports of microfilaremia have been made in Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Nigeria, and Sudan, and possibly rare cases in Chad, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Uganda, and Zambia.[11] Of the 10 countries that have high rates of infection, about 40% of the people who live in the area have reported being infected with the worm in the past. The population in high-risk areas is about 14.4 million; in addition, 15.2 million people live in areas where around 20–40% of people admitted to having the worm in the past.[9]

Epidemiological studies have been emphasized in the western part of Africa. In this area, the disease is considered endemic. A study conducted by the Research Foundation in Tropical Diseases and Environment in 2002 had a sample of 1458 persons, spanning 16 different villages, and found Loa loa presence in these villages ranging from 2.22 to 19.23% of the population. The disease was found to be slightly more prevalent in men.[15]

In a different country in western Africa, a cross-sectional community survey was conducted in Gabon, Africa. The study was performed by the department of Tsamba-Magotsi from August 2008 to February 2009. The study of 1,180 subjects evaluated the presence of microfilaria using microscopy. The carriage rate of L. loa in the subjects tested was 5%. This rate falls within the range of the study listed above.[16]

In the western part of Africa, an increase in prevalence has been associated with the distribution of ivermectin, which is used to prevent the infection of onchocerciasis, which is also very prevalent in the same region. Patients with L. loa who are treated with ivermectin have extreme adverse effects, including death. Therefore, a prevalence mapping system was created called REMO. REMO is used to determine which areas to distribute the ivermectin based on lower levels of L. loa prevalence. The area discovered to be the most overlapping was where Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo overlap.[3]

A study performed to review reported cases of L. loa in nonendemic countries in the past 25 years reviewed 102 cases of imported loiasis, 61 of them from Europe and 31 from the US. Three-quarters of the infestations were acquired in three countries considered endemic: Cameroon, Nigeria, and Gabon. In the subjects viewed, peripheral blood microfilariae were detected 61.4% of the time, eye worm migration 53.5% of the time, and Calabar swellings 41.6% of the time. A trend appeared in the symptoms of the patients where Calabar swellings and eosinophilia were more common among travelers. African immigrants tended to have microfilaremia. Eye worm migration was observed in a similar proportion between the two groups. Only 35 of the patients underwent clinical follow-up. The researchers concluded that L. loa would end up migrating to Europe and the United States, due to increased travel to already endemic regions.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ Cobbold, T. S. (1864). Entozoa, an introduction to the study of helminthology, with reference more particularly to the internal parasites of man. London: Groombridge and Sons. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.46771.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Schmidt, Gerald et al. "Foundations of Parasitology". 7th ed. McGraw Hill, New York, NY, 2005.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Thomson, MC; Obsomer, V; Dunne, M; Connor, SJ; Molyneux, DH (2000). "Satellite mapping of Loa loa prevalence in relation to ivermectin use in west and central Africa". The Lancet. 356 (9235): 1077–1078. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02733-1. PMID 11009145. S2CID 11743223.

- ↑ Metzger, Wolfram Gottfried; Mordmüller, Benjamin (April 2014). "Loa loa—does it deserve to be neglected?". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 14 (4): 353–357. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70263-9. PMID 24332895.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Turkington, C., & Ashby, B. (2007). Encyclopedia of Infectious Diseases. New York: Facts on File.

- ↑ Harris, Michael. "Loa loa". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 2019-04-26. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ↑ Prevention, CDC – Centers for Disease Control and. "CDC – Loiasis – Biology". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- ↑ Whittaker, C; Walker, M; Pion, SDS; Chesnais, CB; Boussinesq, M; Basáñez, MG (April 2018). "The Population Biology and Transmission Dynamics of Loa loa". Trends in Parasitology. 34 (4): 335–350. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2017.12.003. PMID 29331268. S2CID 4545820.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2015 January 20). Parasites – Loiasis. Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/loiasis/ Archived 2023-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Agbolade, O.M.; Akinboye, D.O.; Ogunkola, O. (2005). "Loa loa and Mansonella perstans: neglected human infections that need control in Nigeria". Afr. J. Biotechnol. 4: 1554–1558.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Padgett, J. J.; Jacobsen, K. H. (2008). "Loiasis: African eye worm". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 102 (10): 983–989. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.03.022. PMID 18466939.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Zierhut, M., Pavesio, C., Ohno, S., Oréfice, F., Rao, N. A. (2014). Intraocular Inflammation. Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York.

- ↑ Holmes, D (2013). "Loa loa: neglected neurology and nematodes". The Lancet. Neurology. 12 (7): 631–632. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70139-X. PMID 23769594. S2CID 140206733.

- ↑ Prevention, CDC-Centers for Disease Control and (2019-04-18). "CDC - Loiasis - Resources for Health Professionals". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-04-26. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ↑ Wanji, S.; Tendongfor, N.; Esum, M.; Ndindeng, S.; Enyong, P. (2003). "Epidemiology of concomitant infections due to Loa loa, Mansonella perstans, and Onchocerca volvulus in rain forest villages of Cameroon". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 192 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1007/s00430-002-0154-x. PMID 12592559. S2CID 42438020.

- ↑ Manego, R.; Mombo-Ngoma, Witte; Held, Gmeiner; Gebru (2017). "Demography, maternal health and the epidemiology of malaria and other major infectious diseases in the rural department Tsamba-Magotsi, Ngounie Province, in central African Gabon". BMC Public Health. 17 (1): 130. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4045-x. PMC 5273856. PMID 28129759.

- ↑ Antinori, S.; Schifanella, Million; Galimberti, Ferraris; Mandia (2012). "Imported Loa loa filariasis: Three cases and a review of cases reported in nonendemic countries in the past 25 years. International Journal of Infectious Diseases IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases". 16 (9): E649–E662. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.05.1023. PMID 22784545.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- Taxonomy Browser: Loa Loa. Archived 2023-03-25 at the Wayback Machine National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).