Levofloxacin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Levaquin, Tavanic, Iquix, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Fluoroquinolone |

| WHO AWaRe | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, IV, eye drops |

| Defined daily dose | 0.24 g (inhalation) 0.5 g (by mouth) 0.5 g (parenteral)[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Systemic: Monograph Eyes: Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697040 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 99%[2] |

| Protein binding | 31%[2] |

| Metabolism | <5% desmethyl and N-oxide metabolites |

| Elimination half-life | 6.9 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Kidney, mostly unchanged (83%)[2] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H20FN3O4 |

| Molar mass | 361.373 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.5±0.1 [3] g/cm3 |

| |

| |

Levofloxacin, sold under the trade names Levaquin among others, is an antibiotic.[4] It is used to treat a number of bacterial infections including acute bacterial sinusitis, pneumonia, H. pylori (in combination with other medications), urinary tract infections, chronic prostatitis, and some types of gastroenteritis.[4] Along with other antibiotics it may be used to treat tuberculosis, meningitis, or pelvic inflammatory disease.[4] Use is generally recommended only when other options are not available.[5] It is available by mouth, intravenously,[4] and in eye drop form.[6]

Common side effects include nausea, diarrhea, and trouble sleeping.[4] Serious side effects may include tendon rupture, tendon inflammation, seizures, psychosis, and potentially permanent peripheral nerve damage.[4] Tendon damage may appear months after treatment is completed.[4] People may also sunburn more easily.[4] In people with myasthenia gravis, muscle weakness and breathing problems may worsen.[4] While use during pregnancy is not recommended, risk appears to be low.[7] The use of other medications in this class appear to be safe while breastfeeding; however, the safety of levofloxacin is unclear.[7] Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic of the fluoroquinolone drug class.[7] It usually results in death of the bacteria.[4] It is the left-handed isomer of the medication ofloxacin.[7]

Levofloxacin was patented in 1985 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1996.[4][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[4] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.44–0.95 per week of treatment.[10] In the United States a week of treatment costs about $50–100.[11] In 2017, it was the 165th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[12][13]

Medical uses

Levofloxacin is used to treat infections including: respiratory tract infections, cellulitis, urinary tract infections, prostatitis, anthrax, endocarditis, meningitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, traveler's diarrhea, tuberculosis, and plague[4][14] and is available by mouth, intravenously,[4] and in eye drop form.[6]

As of 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended that "serious side effects associated with fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs generally outweigh the benefits for patients with acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis, and uncomplicated urinary tract infections who have other treatment options. For patients with these conditions, fluoroquinolones should be reserved for those who do not have alternative treatment options."[15]

Levofloxacin is used for the treatment of pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and abdominal infections. As of 2007 the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society recommended levofloxacin and other respiratory fluoroquinolines as first line treatment for community acquired pneumonia when co-morbidities such as heart, lung, or liver disease are present or when in-patient treatment is required.[16] Levofloxacin also plays an important role in recommended treatment regimens for ventilator-associated and healthcare-associated pneumonia.[17]

As of 2010 it was recommended by the IDSA as a first-line treatment option for catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adults.[18] In combination with metronidazole it is recommended as one of several first-line treatment options for adult patients with community-acquired intra-abdominal infections of mild-to-moderate severity.[19] The IDSA also recommends it in combination with rifampicin as a first-line treatment for prosthetic joint infections.[20] The American Urological Association recommends levofloxacin as a first-line treatment to prevent bacterial prostatitis when the prostate is biopsied.[21] and as of 2004 it was recommended to treat bacterial prostatitis by the NIH research network studying the condition.[22]

Levofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones have also been widely used for the treatment of uncomplicated community-acquired respiratory and urinary tract infections, indications for which major medical societies generally recommend the use of older, narrower spectrum drugs to avoid fluoroquinolone resistance development. Due to its widespread use, common pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae have developed resistance. In many countries as of 2013, resistance rates among healthcare-associated infections with these pathogens exceeded 20%.[23][24]

Levofloxacin is also used as antibiotic eye drops to prevent bacterial infection. Usage of levofloxacin eye drops, along with an antibiotic injection of cefuroxime or penicillin during cataract surgery, has been found to lower the chance of developing endophthalmitis, compared to eye drops or injections alone.[25]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

According to the FDA approved prescribing information, levofloxacin is pregnancy category C.[14] This designation indicates that animal reproduction studies have shown adverse effects on the fetus and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans, but the potential benefit to the mother may in some cases outweigh the risk to the fetus. Available data point to a low risk for the unborn child.[7] Exposure to quinolones, including levofloxacin, during the first-trimester is not associated with an increased risk of stillbirths, premature births, birth defects, or low birth weight.[26]

Levofloxacin does penetrate into breastmilk, though the concentration of levofloxacin in the breastfeeding infant is expected to be low.[27] Due to potential risks to the baby, the manufacturer does not recommend that nursing mothers take levofloxacin.[14] However, the risk appears to be very low, and levofloxacin can be used in breastfeeding mothers with proper monitoring of the infant, combined with delaying breastfeeding for 4–6 hours after taking levofloxacin.[27]

Children

Levofloxacin is not approved in most countries for the treatment of children except in unique and life-threatening infections because it is associated with an elevated risk of musculoskeletal injury in this population, a property it shares with other fluoroquinolones.

In the United States levofloxacin is approved for the treatment of anthrax and plague in children over six months of age.[14]

Levofloxacin is recommended by the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society and the Infectious Disease Society of America as a first-line treatment for pediatric pneumonia caused by penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, and as a second-line agent for the treatment of penicillin-sensitive cases.[28]

In one study,[14][29] 1534 juvenile patients (age 6 months to 16 years) treated with levofloxacin as part of three efficacy trials were followed up to assess all musculoskeletal events occurring up to 12 months post-treatment. At 12 months follow-up the cumulative incidence of musculoskeletal adverse events was 3.4%, compared to 1.8% among 893 patients treated with other antibiotics. In the levafloxacin-treated group, approximately two-thirds of these musculoskeletal adverse events occurred in the first 60 days, 86% were mild, 17% were moderate, and all resolved without long-term sequelae.

Spectrum of activity

Levofloxacin and later generation fluoroquinolones are collectively referred to as "respiratory quinolones" to distinguish them from earlier fluoroquinolones which exhibited modest activity toward the important respiratory pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae.[30]

The drug exhibits enhanced activity against the important respiratory pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae relative to earlier fluoroquinolone derivatives like ciprofloxacin. For this reason, it is considered a "respiratory fluoroquinolone" along with more recently developed fluoroquinolones such as moxifloxacin and gemifloxacin. It is less active than ciprofloxacin against Gram-negative bacteria, especially Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and lacks the anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) activity of moxifloxacin and gemifloxacin.[31][32][33][34] Levofloxacin has shown moderate activity against anaerobes, and is about twice as potent as ofloxacin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacteria, including Mycobacterium avium complex.[35]

Its spectrum of activity includes most strains of bacterial pathogens responsible for respiratory, urinary tract, gastrointestinal, and abdominal infections, including Gram negative (Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Moraxella catarrhalis, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa), Gram positive (methicillin-sensitive but not methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Enterococcus faecalis, and Streptococcus pyogenes), and atypical bacterial pathogens (Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae). Compared to earlier antibiotics of the fluoroquinoline class such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin exhibits greater activity towards Gram-positive bacteria[31] but lesser activity toward Gram-negative bacteria,[36] especially Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Resistance

Resistance to fluoroquinolones is common in staphylococcus and pseudomonas. Resistance occurs in multiple ways. One mechanism is by an alteration in topoisomerase IV enzyme. A double mutant form of S. pneumoniae Gyr A + Par C bearing Ser-81-->Phe and Ser-79-->Phe mutations were eight to sixteen times less responsive to ciprofloxacin.[37]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 0.24 g (inhalation) or 0.5 g (by mouth) or 0.5 g (parenteral)[1]

Contraindications and interactions

Package inserts mention that levofloxacin is to be avoided in patients with a known hypersensitivity to levofloxacin or other quinolone drugs.[14][38]

Like all fluoroquinolines, levofloxacin is contraindicated in patients with epilepsy or other seizure disorders, and in patients who have a history of quinolone-associated tendon rupture.[14][38]

Levofloxacin may prolong the QT interval in some people, especially the elderly, and levofloxacin should not be used for people with a family history of Long QT syndrome, or who have long QT, chronic low potassium, it should not be prescribed with other drugs that prolong the QT interval.[14]

Unlike ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin does not appear to deactivate the drug metabolizing enzyme CYP1A2. Therefore, drugs that use that enzyme, like theophylline, do not interact with levofloxacin. It is a weak inhibitor of CYP2C9,[39] suggesting potential to block the breakdown of warfarin and phenprocoumon. This can result in more action of drugs like warfarin, leading to more potential side effects, such as bleeding.[40]

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in combination with high dose fluoroquinolone therapy may lead to seizures.[41]

When levofloxacin is taken with anti-acids containing magnesium hydroxide or aluminum hydroxide, the two combine to form insoluble salts that are difficult to absorb from the intestines. Peak serum concentrations of levofloxacin may be reduced by 90% or more, which can prevent the levofloxacin from working. Similar results have been reported when levofloxacin is taken with iron supplements and multi-vitamins containing zinc.[42][43]

A 2011 review examining musculoskeletal complications of fluoroquinolones proposed guidelines with respect to administration to athletes, that called for avoiding all use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics if possible, and if they are used: ensure there is informed consent about the musculoskeletal risks, and inform coaching staff; do not use any corticosteroids if fluoroquinolones are used; consider dietary supplements of magnesium and antioxidants during treatment; reduce training until the course of antibiotic is finished and then carefully increase back to normal; and monitor for six months after the course is finished, and stop all athletic activity if symptoms emerge.[44]

Side effects

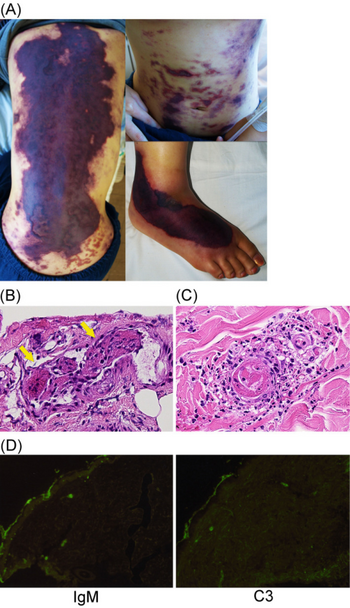

Adverse effects are typically mild to moderate. However, severe, disabling, and potentially irreversible adverse effects sometimes occur, and for this reason use it is recommended that use of fluoroquinolones be limited.

Prominent among these are adverse effects that became the subject of a black box warning by the FDA in 2016.[15] The FDA wrote: "An FDA safety review has shown that fluoroquinolones when used systemically (i.e. tablets, capsules, and injectable) are associated with disabling and potentially permanent serious adverse effects that can occur together. These adverse effects can involve the tendons, muscles, joints, nerves, and central nervous system."[15] Rarely, tendinitis or tendon rupture may occur due to fluoroquinolone antibiotics, including levofloxacin.[45] Such injuries, including tendon rupture, has been observed up to 6 months after cessation of treatment; higher doses of fluoroquinolones, being elderly, transplant patients, and those with a current or historical corticosteroid use are at elevated risk.[46][47] The U.S. label for levofloxacin also contains a black box warning for the exacerbation of the symptoms of the neurological disease myasthenia gravis.[14][48] Similarly, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency recommendations warn of rare but disabling and potentially irreversible adverse effects, and to recommend limiting use of these drugs.[49] Increasing age and corticosteroid use appears to increase the risk of musculoskeletal complications.[44]

A wide variety of other uncommon but serious adverse events have been associated with fluoroquinolone use, with varying degrees of evidence supporting causation. These include anaphylaxis, hepatotoxicity, central nervous system effects including seizures and psychiatric effects, prolongation of the QT interval, blood glucose disturbances, and photosensitivity, among others.[14][38] Levofloxacin may produce fewer of these rare serious adverse effects than other fluoroquinolones.[50]

There is some disagreement in the medical literature regarding whether and to what extent levofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones produce serious adverse effects more frequently than other broad spectrum antibacterial drugs.[51][52][53][54]

With regard to more usual adverse effects, in pooled results from 7537 patients exposed to levofloxacin in 29 clinical trials, 4.3% discontinued treatment due to adverse drug reactions. The most common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Overall, 7% of patients experienced nausea, 6% headache, 5% diarrhea, 4% insomnia, along with other adverse reactions experienced at lower rates.[14]

Administration of levofloxacin or other broad spectrum antibiotics is associated with Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea which may range in severity from mild diarrhea to fatal colitis. Fluoroquinoline administration may be associated with the acquisition and outgrowth of a particularly virulent Clostridium strain.[55]

More research is needed to determine the best dose and length of treatment.[56]

Overdose

Overdosing experiments in animals showed loss of body control and drooping, difficulty breathing, tremors, and convulsions. Doses in excess of 1500 mg/kg orally and 250 mg/kg IV produced significant mortality in rodents.[14]

In the event of an acute overdosage, authorities recommend unspecific standard procedures such as emptying the stomach, observing the patient and maintaining appropriate hydration. Levofloxacin is not efficiently removed by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.[14]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

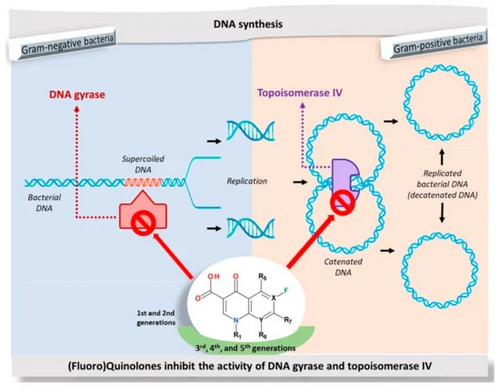

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that is active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Like all quinolones, it functions by inhibiting the DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, two bacterial type II topoisomerases.[58] Topoisomerase IV is necessary to separate DNA that has been replicated (doubled) prior to bacterial cell division. With the DNA not being separated, the process is stopped, and the bacterium cannot divide. DNA gyrase, on the other hand, is responsible for supercoiling the DNA, so that it will fit in the newly formed cells. Both mechanisms amount to killing the bacterium. Levofloxacin acts as a bactericide.[59]

As of 2011 the mechanism of action for the drug's musculoskeletal complications were not clear.[44]

Pharmacokinetics

Levofloxacin is rapidly and essentially completely absorbed after oral administration, with a plasma concentration profile over time that is essentially identical to that obtained from intravenous administration of the same amount over 60 minutes. As such, the intravenous and oral formulations of levofloxacin are considered interchangeable.[14] Levofloxacin's ability to bind to proteins in the body ranges from 24-38%.[56]

The drug undergoes widespread distribution into body tissues. Peak levels in skin are achieved 3 hours after administration and exceed those in plasma by a factor of 2. Similarly, lung tissue concentrations range from two-fold to five-fold higher than plasma concentrations in the 24 hours after a single dose.

The mean terminal plasma elimination half-life of levofloxacin ranges from approximately 6 to 8 hours following single or multiple doses of levofloxacin given orally or intravenously. Elimination occurs mainly via excretion of unmetabolized drug in the urine. Following oral administration, 87% of an administered dose was recovered in the urine as unchanged drug within 2 days. Less than 5% was recovered in the urine as the desmethyl and N-oxide metabolites, the only metabolites identified in humans.

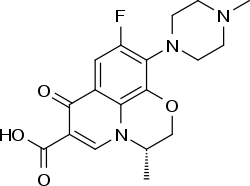

Chemistry

Levofloxacin is the levo isomer of the racemate ofloxacin, another quinolone antimicrobial agent.[60] Levofloxacin, a chiral fluorinated carboxyquinolone, is the pure (−)-(S)-enantiomer of the racemic ofloxacin.[61][62] Distinct functional groups on this molecules include a hydroxyl group, carbonyl group, and an aromatic ring.[63]

Levofloxacin is the S-enantiomer and it binds more effectively to the DNA gyrase enzyme and topoisomerase IV than its counterpart.[64][56]

The substance is used as the hemihydrate, which has the empirical formula C18H20FN3O4 · ½ H2O and a molecular mass of 370.38 g/mol. Levofloxacin is a light-yellowish-white to yellow-white crystal or crystalline powder.[14] A major issue in the synthesis of Levofloxacin is identifying correct entries into the benzoxazine core in order to produce the correct chiral form.[65]

History

Levofloxacin is a third-generation fluoroquinolone, being one of the isomers of ofloxacin, which was a broader-spectrum conformationally locked analog of norfloxacin; both ofloxacin and levofloxaxin were synthesized and developed by scientists at Daiichi Seiyaku.[66] The Daiichi scientists knew that ofloxacin was racemic, but tried unsuccessfully to separate the two isomers; in 1985 they succeeded in separately synthesizing the pure levo form and showed that it was less toxic and more potent than the other form.[67][68]

It was first approved for marketing in Japan in 1993 for oral administration, and Daiichi marketed it there under the brand name Cravit.[68] Daiichi, working with Johnson & Johnson as it had with ofloxacin, obtained FDA approval in 1996 under the brand name Levaquin[67] to treat bacterial sinusitus, bacterial exacerbations of bronchitis, community-acquired pneumonia, uncomplicated skin infections, complicated urinary tract infections, and acute pyelonephritis.[14]

Levofloxacin is marketed by Sanofi-Aventis under a license agreement signed with Daiichi in 1993 under the trade name "Tavanic".[69]

Levofloxacin had reached blockbuster status by this time; combined worldwide sales of levofloxacin and ofloxacin for J&J alone were US$1.6 billion in 2009.[69]

The term of the levofloxacin United States patent was extended by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office 810 days under the provisions of the Hatch Waxman Amendment so that the patent would expire in 2010 instead of 2008.[67] This extension was challenged by generic drug manufacturer Lupin Pharmaceuticals, which did not challenge the validity of the patent, but only the validity of the patent extension, arguing that the patent did not cover a "product" and so Hatch-Waxman was not available for extensions.[67] The federal patent court ruled in favor of J&J and Daiichi, and generic versions of levofloxacin did not enter the U.S. market until 2009.[67][69]

Society and culture

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.44–0.95 per week of treatment.[10] In the United States a week of treatment costs about $50–100.[11] In 2017, it was the 165th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[12][13]

-

Levofloxacin costs (US)

-

Levofloxacin prescriptions (US)

Availability

Levofloxacin is available in tablet form, injection, and oral solution.[14]

Usage

The FDA estimated that in 2011 over 23 million outpatient prescriptions for fluoroquinolones, of which levofloxacin made up 28%, were filled in the United States.[70]

Litigation

As of 2012, Johnson and Johnson was facing around 3400 state and federal lawsuits filed by people who claimed tendon damage from levofloxacin; about 1900 pending in a class action at the United States District Court in Minnesota[71] and about 1500 pending at a district court in New Jersey.[72][73]

In October 2012, J&J settled 845 cases in the Minnesota action, after Johnson and Johnson prevailed in three of the first four cases to go to trial. By May 2014, all but 363 cases had been settled or adjudicated.[73][74][75]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Zhanel GG, Fontaine S, Adam H, Schurek K, Mayer M, Noreddin AM, Gin AS, Rubinstein E, Hoban DJ (2006). "A Review of New Fluoroquinolones : Focus on their Use in Respiratory Tract Infections". Treat Respir Med. 5 (6): 437–65. doi:10.2165/00151829-200605060-00009. PMID 17154673.

- ↑ "Levofloxacin_msds". Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 "Levofloxacin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ "Press Announcements - FDA updates warnings for fluoroquinolone antibiotics on risks of mental health and low blood sugar adverse reactions". www.fda.gov. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Levofloxacin ophthalmic medical facts from Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Yaffe, Gerald G. Briggs, Roger K. Freeman, Sumner J. (2011). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation : a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 828. ISBN 9781608317080. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 500. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Levofloxacin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 102. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Levofloxacin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 "US Label" (PDF). 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2016.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling adverse effects that can occur". US Department of Health and Human Services. US Food and Drug Administration. 25 August 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- ↑ Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. (March 2007). "Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults". Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 Suppl 2: S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159. PMID 17278083.

- ↑ File TM (August 2010). "Recommendations for treatment of hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: review of recent international guidelines". Clin. Infect. Dis. 51 Suppl 1: S42–7. doi:10.1086/653048. PMID 20597671.

- ↑ Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, et al. (March 2010). "Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clin. Infect. Dis. 50 (5): 625–63. doi:10.1086/650482. PMID 20175247.

- ↑ Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. (January 2010). "Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clin. Infect. Dis. 50 (2): 133–64. doi:10.1086/649554. PMID 20034345.

- ↑ Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. (January 2013). "Executive summary: diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America" (PDF). Clin. Infect. Dis. 56 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1093/cid/cis966. PMID 23230301. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ American Urological Association. 2016 The Prevention and Treatment of the More Common Complications Related to Prostate Biopsy Update Archived 20 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Schaeffer AJ (September 2004). "NIDDK-sponsored chronic prostatitis collaborative research network (CPCRN) 5-year data and treatment guidelines for bacterial prostatitis". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 24 Suppl 1: S49–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.02.009. PMID 15364307.

- ↑ ECDC (2014). "Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2014" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2016.

- ↑ CDC. "Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Gower EW, Lindsley K, Tulenko SE, Nanji AA, Leyngold I, McDonnell PJ (2017). "Perioperative antibiotics for prevention of acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD006364. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006364.pub3. PMC 5375161. PMID 28192644.

- ↑ Ziv A, Masarwa R, Perlman A, Ziv D, Matok I (March 2018). "Pregnancy Outcomes Following Exposure to Quinolone Antibiotics - a Systematic-Review and Meta-Analysis". Pharm. Res. 35 (5): 109. doi:10.1007/s11095-018-2383-8. PMID 29582196.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "TOXNET: Levofloxacin". toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ↑ Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, Alverson B, Carter ER, Harrison C, Kaplan SL, Mace SE, McCracken GH, Moore MR, St Peter SD, Stockwell JA, Swanson JT (2011). "The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clin. Infect. Dis. 53 (7): e25–76. doi:10.1093/cid/cir531. PMID 21880587.

- ↑ Noel GJ, Bradley JS, Kauffman RE (October 2007). "Comparative safety profile of levofloxacin in 2523 children with a focus on four specific musculoskeletal disorders". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 26 (10): 879–91. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3180cbd382. PMID 17901792.

- ↑ Wispelwey B, Schafer KR (November 2010). "Fluoroquinolones in the management of community-acquired pneumonia in primary care". Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 8 (11): 1259–71. doi:10.1586/eri.10.110. PMID 21073291.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Lafredo SC, Foleno BD, Fu KP (1993). "Induction of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to quinolones in vitro". Chemotherapy. 39 (1): 36–9. doi:10.1159/000238971. PMID 8383031.

- ↑ Fu KP, Lafredo SC, Foleno B, et al. (April 1992). "In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of levofloxacin (l-ofloxacin), an optically active ofloxacin". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36 (4): 860–6. doi:10.1128/aac.36.4.860. PMC 189464. PMID 1503449.

- ↑ Blondeau JM (May 1999). "A review of the comparative in-vitro activities of 12 antimicrobial agents, with a focus on five new respiratory quinolones'". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43 Suppl B (90002): 1–11. doi:10.1093/jac/43.suppl_2.1. PMID 10382869.

- ↑ Cormican MG, Jones RN (January 1997). "Antimicrobial activity and spectrum of LB20304, a novel fluoronaphthyridone". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41 (1): 204–11. doi:10.1128/AAC.41.1.204. PMC 163688. PMID 8980783.

- ↑ John A. Bosso (1998). "New and Emerging Quinolone Antibiotics". Journal of Infectious Disease Pharmacotherapy. 2 (4): 61–76. doi:10.1300/J100v02n04_06. ISSN 1068-7777.

- ↑ Yamane N, Jones RN, Frei R, Hoban DJ, Pignatari AC, Marco F (April 1994). "Levofloxacin in vitro activity: results from an international comparative study with ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin". J Chemother. 6 (2): 83–91. doi:10.1080/1120009X.1994.11741134. PMID 8077990.

- ↑ Hawkey, PM (May 2003). "Mechanisms of quinolone action and microbial response". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 51 Suppl 1 (90001): 29–35. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg207. PMID 12702701.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 UK electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC) Levofloxacin 250mg and 500mg Tablets Archived 26 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Last revised in July 2013

- ↑ Zhang L, Wei MJ, Zhao CY, Qi HM (December 2008). "Determination of the inhibitory potential of 6 fluoroquinolones on CYP1A2 and CYP2C9 in human liver microsomes". Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 29 (12): 1507–14. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00908.x. PMID 19026171.

- ↑ Schelleman H, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Han X, Kimmel SE, Hennessy S (November 2008). "Warfarin with fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, or azole antifungals: interactions and the risk of hospitalization for gastrointestinal bleeding". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 84 (5): 581–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2008.150. PMC 2574587. PMID 18685566.

- ↑ Domagala JM (April 1994). "Structure-activity and structure-side-effect relationships for the quinolone antibacterials". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33 (4): 685–706. doi:10.1093/jac/33.4.685. PMID 8056688. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009.

- ↑ Rodvold KA, Piscitelli SC (August 1993). "New oral macrolide and fluoroquinolone antibiotics: an overview of pharmacokinetics, interactions, and safety". Clin. Infect. Dis. 17 Suppl 1: S192–9. doi:10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_1.s192. PMID 8399914.

- ↑ Tanaka M, Kurata T, Fujisawa C, et al. (October 1993). "Mechanistic study of inhibition of levofloxacin absorption by aluminum hydroxide". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37 (10): 2173–8. doi:10.1128/aac.37.10.2173. PMC 192246. PMID 8257141.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Hall, MM; Finnoff, JT; Smith, J (February 2011). "Musculoskeletal complications of fluoroquinolones: guidelines and precautions for usage in the athletic population". PM&R : The Journal of Injury, Function, and Rehabilitation. 3 (2): 132–42. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.10.003. PMID 21333952.

- ↑ Stephenson AL, Wu W, Cortes D, Rochon PA (September 2013). "Tendon Injury and Fluoroquinolone Use: A Systematic Review". Drug Saf. 36 (9): 709–21. doi:10.1007/s40264-013-0089-8. PMID 23888427.

- ↑ Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG (June 2003). "Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literature". Clin. Infect. Dis. 36 (11): 1404–10. doi:10.1086/375078. PMID 12766835.

- ↑ Kim GK (April 2010). "The Risk of Fluoroquinolone-induced Tendinopathy and Tendon Rupture: What Does The Clinician Need To Know?". J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 3 (4): 49–54. PMC 2921747. PMID 20725547.

- ↑ Jones SC, Sorbello A, Boucher RM (October 2011). "Fluoroquinolone-associated myasthenia gravis exacerbation: evaluation of postmarketing reports from the US FDA adverse event reporting system and a literature review". Drug Saf. 34 (10): 839–47. doi:10.2165/11593110-000000000-00000. PMID 21879778.

- ↑ "Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: New restrictions and precautions for use due to very rare reports of disabling and potentially long-lasting or irreversible side effects". Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ Carbon C (2001). "Comparison of side effects of levofloxacin versus other fluoroquinolones". Chemotherapy. 47 Suppl 3 (3): 9–14, discussion 44–8. doi:10.1159/000057839. PMID 11549784.

- ↑ Liu HH (May 2010). "Safety profile of the fluoroquinolones: focus on levofloxacin". Drug Saf. 33 (5): 353–69. doi:10.2165/11536360-000000000-00000. PMID 20397737.

- ↑ Karageorgopoulos DE, Giannopoulou KP, Grammatikos AP, Dimopoulos G, Falagas ME (March 2008). "Fluoroquinolones compared with beta-lactam antibiotics for the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". CMAJ. 178 (7): 845–54. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071157. PMC 2267830. PMID 18362380.

- ↑ Lipsky BA, Baker CA (February 1999). "Fluoroquinolone toxicity profiles: a review focusing on newer agents". Clin. Infect. Dis. 28 (2): 352–64. doi:10.1086/515104. PMID 10064255.

- ↑ Stahlmann R, Lode HM (July 2013). "Risks associated with the therapeutic use of fluoroquinolones". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 12 (4): 497–505. doi:10.1517/14740338.2013.796362. PMID 23651367.

- ↑ Vardakas KZ, Konstantelias AA, Loizidis G, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME (November 2012). "Risk factors for development of Clostridium difficile infection due to BI/NAP1/027 strain: a meta-analysis". Int. J. Infect. Dis. 16 (11): e768–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.07.010. PMID 22921930.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 McGregor, JC; Allen, GP; Bearden, DT (October 2008). "Levofloxacin in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections and acute pyelonephritis". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 4 (5): 843–53. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S3426. PMC 2621400. PMID 19209267.

- ↑ Rusu, Aura; Lungu, Ioana-Andreea; Moldovan, Octavia-Laura; Tanase, Corneliu; Hancu, Gabriel (August 2021). "Structural Characterization of the Millennial Antibacterial (Fluoro)Quinolones—Shaping the Fifth Generation". Pharmaceutics. 13 (8): 1289. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13081289. ISSN 1999-4923.

- ↑ Drlica K, Zhao X (1 September 1997). "DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones". Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 61 (3): 377–92. doi:10.1128/.61.3.377-392.1997. PMC 232616. PMID 9293187. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ Mutschler, Ernst; Schäfer-Korting, Monika (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 814f. ISBN 978-3-8047-1763-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "STATISTICAL REVIEW AND EVALUATION" (PDF). USA: FDA. 21 November 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2012.

- ↑ Morrissey, I.; Hoshino, K.; Sato, K.; Yoshida, A.; Hayakawa, I.; Bures, MG.; Shen, LL. (August 1996). "Mechanism of differential activities of ofloxacin enantiomers" (PDF). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 40 (8): 1775–84. doi:10.1128/AAC.40.8.1775. PMC 163416. PMID 8843280. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2011.

- ↑ Kannappan, Valliappan; Mannemala, Sai Sandeep (7 June 2014). "Multiple Response Optimization of a HPLC Method for the Determination of Enantiomeric Purity of S-Ofloxacin". Chromatographia. 77 (17–18): 1203–1211. doi:10.1007/s10337-014-2699-4.

- ↑ Mouzam, M. I.; Dehghan, M. H. G.; Asif, S.; Sahuji, T.; Chudiwal, P. Preparation of a novel floating ring capsule-type dosage form for stomach specific delivery. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2011, 19, 85-93.

- ↑ McGregor, J. C.; Allen, G. P.; Bearden, D. T. Levofloxacin in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections and acute pyelonephritis. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2008, 4, 843-853.

- ↑ ) John F. Bower; Janjira Rujirawanich; Timothy Gallagher N -Heterocycle construction via cyclic sulfamidates. Applications in synthesis.

- ↑ Walter Sneader (31 October 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 67.3 67.4 Staff, Fish and Richardson. memorANDA, Q2, 2009 Archived 27 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. VIII. Cites US Patent 5,053,407 Archived 26 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 S Atarashi from Daiichi. Research and Development of Quinolones in Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. Archived 12 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed August 25, 2016

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Katie Taylor (October 2010). "Drug In Focus: Levofloxacin". GenericsWeb. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires label changes to warn of risk for possibly permanent nerve damage from antibacterial fluoroquinolone drugs taken by mouth or by injection". US Department of Health and Human Services. US Food and Drug Administration. 16 January 2016. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016.

- ↑ Judge John R. Tunheim. "Levaquin MDL". USA: US Courts. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ Charles Toutant (6 July 2009). "Litigation Over Johnson & Johnson Antibiotic Levaquin Designated N.J. Mass Tort". New Jersey Law Journal. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Margaret Cronin Fisk and Beth Hawkins for Bloomberg News. Nov 1, 2012 Johnson & Johnson Settles 845 Levaquin Lawsuits Archived 8 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Johnson & Johnson Settles 845 Levaquin Lawsuits - Businessweek". Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- ↑ "Levaquin MDL | United States District Court - District of Minnesota, United States District Court - District of Minnesota". Archived from the original on 26 October 2012.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1: long volume value

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- Use dmy dates from January 2013

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Articles with Curlie links

- Enantiopure drugs

- Fluoroquinolone antibiotics

- Nitrogen heterocycles

- Oxygen heterocycles

- Piperazines

- GABAA receptor negative allosteric modulators

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- RTT

- Japanese inventions

- Sanofi

- Johnson & Johnson brands

- Janssen Pharmaceutica