Legius syndrome

| Legius syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

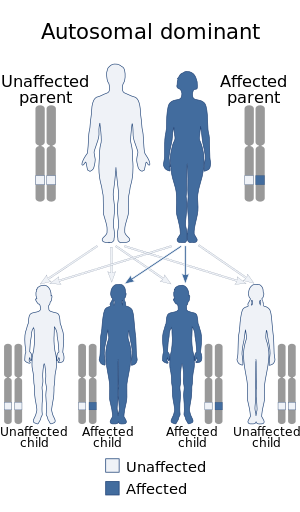

| This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. | |

| Symptoms | café au lait spots; +/- learning disabilities[1] |

| Usual onset | at birth |

| Causes | Mutations in the SPRED1 gene[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical findings, Genetic test[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1) |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, Speech therapy[1][4] |

| Prognosis | good |

| Frequency | rare (estimated at 1:46,000-1:75,000)[1] |

Legius syndrome (LS) is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by cafe au lait spots.[2] It was first described in 2007 and is often mistaken for neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). It is caused by mutations in the SPRED1 gene.[5][6] It is also known as neurofibromatosis type 1-like syndrome (NFLS).[4]

Symptoms and signs

Nearly all individuals with Legius syndrome show multiple café au lait spots on their skin.[7] Symptoms may include:[1]

- Freckles in the axillary and inguinal skin fold

- Lipomas, developing in adulthood

- Macrocephaly

- Learning disabilities

- ADHD

- Developmental delay

Features common in neurofibromatosis – like Lisch nodules (iris hamartomas diagnosed on slit lamp exam), bone abnormalities, neurofibromas, optic pathway gliomas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors – are absent in Legius syndrome.[4]

-

Legius syndrome

-

Legius syndrome

-

Café au lait spot on right underarm

Cause

Legius syndrome is a phakomatosis[8] and a RASopathy, a developmental syndrome due to germline mutations in genes.[7][9] The condition is autosomal dominant in regards to inheritance and caused by mutations to the SPRED1 gene at chromosome 15, specifically 15q14 (or (GRCh38): 15:38,252,086-38,357,248).[10][11] The gene in question demonstrates almost 100 mutations.[4]

Mechanism

A mutated SPRED1 protein adversely regulates Ras-MAPK signaling, which is a chain of proteins in a cell that sends signals from the surface of a cell to the nucleus which in turn causes the symptoms of this condition.[1][12]

Diagnosis

Genetic testing is necessary to identify the syndrome. The DNA test is necessary sometimes, because symptoms may not be sufficient to definitely diagnose this condition.[3][4][13]

Differential diagnosis

The symptoms of Legius syndrome and NF-1 are very similar; An important difference between Legius syndrome and NF-1 is the absence of tumor growths Lisch nodules and neurofibromas which are common in NF-1.[1]

A genetic test is often the only way to make sure a person has LS and not NF-1; the similarity of symptoms stem from the fact that the different genes affected in the two syndromes code for proteins that carry out a similar task in the same reaction pathway.[medical citation needed]

Treatment

Management of Legius syndrome is done via the following:[1][4]

- Physical therapy

- Speech therapy

- Pharmacologic therapy (e.g. methylphenidate for ADHD)[14]

The prognosis of this condition is generally considered good with appropriate treatment.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Stevenson, David; Viskochil, David; Mao, Rong (1993). "Legius Syndrome". GeneReviews. PMID 20945555. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.update 2015

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [https://web.archive.org/web/20170627230347/https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/legius-syndrome Archived 2017-06-27 at the Wayback Machine "Legius syndrome", Genetics Home Reference, National Institutes of Health

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Legius syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-01-14. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Legius syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ [https://web.archive.org/web/20180103193433/https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/SPRED1 Archived 2018-01-03 at the Wayback Machine "SPRED1", Genetics Home Reference, National Institutes of Health

- ↑ [https://web.archive.org/web/20191011202620/https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/712643 Archived 2019-10-11 at the Wayback Machine "Legius Syndrome Often Mistaken for Neurofibromatosis Type 1", by Allison Gandley, November 18, 2009, Medscape

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "OMIM Entry - # 611431 - LEGIUS SYNDROME". omim.org. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Rosser, Tena (February 2018). "Neurocutaneous Disorders". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 24 (1, Child Neurology): 96–129. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000562. ISSN 1538-6899. PMID 29432239. S2CID 4107835. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ↑ Tidyman, William (2009). "The RASopathies: Developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 19 (3): 230–236. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.001. PMC 2743116. PMID 19467855.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - * 609291 - SPROUTY-RELATED EVH1 DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN 1; SPRED1". www.omim.org. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ "Homo sapiens sprouty related EVH1 domain containing 1 (SPRED1), RefSeq - Nucleotide - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-01-24. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Molina, Julian R.; Adjei, Alex A. (2006-01-01). "The Ras/Raf/MAPK Pathway". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 1 (1): 7–9. doi:10.1016/S1556-0864(15)31506-9. PMID 17409820.

- ↑ "SPRED1 sprouty related EVH1 domain containing 1 - Gene - GTR - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-05-27. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Jakob Storebø Ole (2015). "Benefits and harms of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | Cochrane". Reviews (11): CD009885. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009885.pub2. PMID 26599576. Archived from the original on 2020-11-30. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

Further reading

- MD, Robert P. Erickson; PhD, Anthony J. Wynshaw-Boris MD (2016). Epstein's Inborn Errors of Development: The Molecular Basis of Clinical Disorders of Morphogenesis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190275426. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- Zhang, Jia (2016). "Molecular screening strategies for NF1-like syndromes with café-au-lait macules". Molecular Medicine Reports. 14 (5): 4023–4029. doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5760. PMC 5112360. PMID 27666661. Review

External links

- PubMed Archived 2018-07-25 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- Genodermatoses

- Developmental neuroscience

- Neuro-cardio-facial-cutaneous syndromes

- RASopathies

- Syndromes