Congenital syphilis

| Congenital syphilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Early onset rash of congenital syphilis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms |

|

| Usual onset | Unborn baby, at birth, infancy, and later[2] |

| Types | |

| Causes | Spread from mother to baby of untreated syphilis (Treponema pallidum) during pregnancy or at birth[2] |

| Diagnostic method |

|

| Prevention | Safe sex, adequate screening, early treatment in pregnancy[5] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[6] |

| Medication | Penicillin by injection; Benzylpenicillin (IV), procaine benzylpenicillin (IM), benzathine penicillin G (IM)[6] |

| Frequency | 473 per 100,000 live births worldwide (2016)[7] |

| Deaths | 204,000 worldwide (2016)[7] |

Congenital syphilis is syphilis that occurs when a mother with untreated syphilis passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy.[1] It may be detected in the unborn baby as poor growth, excessive fluid leading to premature birth, or loss of the baby; though some have no signs.[2][8] Features vary widely and may be divided into whether they present before or after age 2-years.[1] Typically there are no signs in the first few weeks of life; though babies may be small and irritable.[1] Features may include fever, rash, large liver and spleen, runny nose, or bone or joint pain.[1][4] There may be yellowish skin and eyes, large glands, pneumonia, meningitis, warty bumps on genitals, deafness, or blindness.[1][5] Untreated babies that survive may develop deformities of the nose, lower legs, forehead, collar bone, jaw, or cheek bone.[1] There may be a perforated or high arched palate, joint disease, and intellectual disability.[1][4] Seizures and cranial nerve palsies may occur in both early and late phases.[1]

It is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum when it infects the baby after crossing the placenta during pregnancy or from contact with a syphilitic sore at birth.[1][8] It is not transmitted during breastfeeding unless there is a syphilitic sore on the mother's breast.[1] Most cases occur due to inadequate screening and treatment during pregnancy.[9] The baby is highly infectious if the rash and snuffles are present.[1] The disease may be suspected from tests on the mother; blood tests and ultrasound.[3] Tests on the baby may include blood, CSF, and medical imaging.[10] Findings may reveal low red blood, low platelets, low sugars, protein in the urine, or low thyroid.[1] The placenta may appear large and pale.[1] Other investigations include testing for HIV.[10]

Prevention is by safe sex to prevent syphilis in the mother, and early screening and treatment in pregnancy.[5] One intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin G given to a pregnant woman early in the illness can prevent congenital syphilis in her baby.[11] Treatment of suspected congenital syphilis is with penicillin by injection; benzylpenicillin, procaine benzylpenicillin, or benzathine penicillin G.[6][10] During times of penicillin unavailability, ceftriaxone may be used.[10] If there is a penicillin allergy, desensitisation may be an option.[10][12]

Syphilis affects around a million pregnancies a year.[13] In 2016, there were around 473 cases of congenital syphilis per 100,000 live births and 204,000 deaths from the disease worldwide.[7] Of 660,000 cases reported in 2016, 143,000 resulted in deaths of unborn babies, 61,000 deaths of newborn babies, 41,000 low birth weights or preterm births, and 109,000 young children diagnosed with congenital syphilis.[14] Around 75% were from the African and Eastern Mediterranean regions.[4] The cost of preventing syphilis in the mother and baby and in treating the disease is generally inexpensive.[11][15] The disease was first described in the sixteenth century.[16] Blood tests for syphilis were introduced in 1906, and it was later shown that spread occurred from the mother.[17]

Signs and symptoms

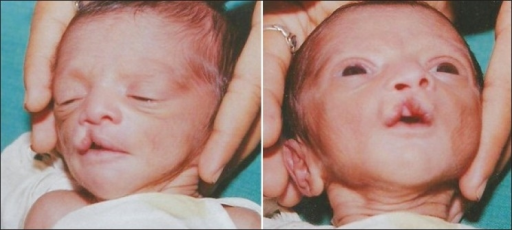

Congenital syphilis may present in the unborn baby, newborn baby or later.[2] Clinical features vary and some differ between early onset, that is presentation before age 2-years of age, and late onset, presentation after age 2-years.[1] Infection in the unborn baby may present as poor growth, non-immune hydrops leading to premature birth or loss of the baby, or no signs.[1][4] Affected newborns mostly initially have no clinical signs.[1] If they have symptoms, they are more likely to be quite sick. [8] These babies are typically small, dehydrated, malnourished, and irritable.[1][8] They characteristically present with a rash, fever, large liver and spleen, and may have a runny and congested nose, and leg pain.[1][4] There may be jaundice, large glands, pneumonia, meningitis, warty bumps on genitals, deafness or blindness.[1][5] Signs in the eyes are less frequent.[1] Untreated babies that survive the early phase may develop skeletal deformities.[1][4] Seizures and cranial nerve palsies may first occur in both early and late phases.[1]

Early

Rash

The rash in a newborn is a prominent feature.[1] It may appear as light coloured patches on the legs and face, dark spots on the soles of feet, small bumps around the mouth, or widespread peeling skin with blisters.[1]

-

Rash of congenital syphilis

-

Rash of congenital syphilis

-

Erosive lesions over natal cleft

-

Erosive lesion over genitals

-

Congenital syphilis rash

Rhinitis

Some babies present with the snuffles; initially clear discharge, it may later become purulent or blood tinged.[1]

-

Runny and congested nose

-

High arched palate, oral fissures, and runny and congested nose

Bone pain

Refusal to move a limb in an infant may result from inflammation around bone or cartilage.[1]

-

Swollen elbow

-

Swollen joints (age 2-months)

-

Swollen knee

Eyes

Eye findings include glaucoma, cataracts, chorioretinitis and uveitis.[1]

-

Congenital syphilis corneal keratitis

-

Congenital syphilis cataract

Other early signs

-

13-day-old infant with cleft lip

Late

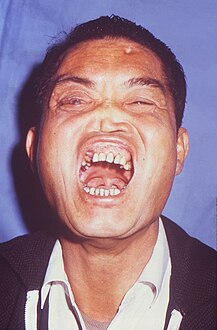

Late onset features include deformity of the nose, lower legs, forehead, collar bone, jaw, and cheek bone.[1] Some of these bone defects can be detected early.[16] There may be a perforated or high arched palate, and recurrent joint disease.[1][4] Other late signs include scarred skin, intellectual disability, hydrocephalus, and juvenile general paresis.[1] Eighth nerve palsy, interstitial keratitis and small notched teeth may appear individually or together; known as Hutchinson triad.[1][18]

-

Late onset: Deformity of nose and palate

-

Hutchinson's teeth

-

Mulberry molar

-

Absent teeth

-

Perforation of palate

-

Perforated hard palate

-

Saddle nose

-

Gumma of face

-

Frontal bossing, mulberry molars, Hutchinson teeth, saddle nose, cataract in right eye

-

Clutton's joints

Cause

Congenital syphilis is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum when it infects the baby after crossing the placenta or from contact with a syphilitic sore at birth.[1][8] It is not transmitted during breastfeeding unless there is an open sore on the mother's breast.[1] The unborn baby can become infected at any time during the pregnancy, and risk of infection is greater as the pregnancy progresses.[1] The previously held theory that infection generally could not occur in the first 4-months of pregnancy has been disproved.[1]

Diagnosis

The disease may be suspected from tests on the mother; blood tests and ultrasound.[3] No specific ultrasound finding precisely indicates congenital syphilis but a large liver or spleen, bowel abnormalities, poor growth, ascites, and hydrops, suggest a syphilis work-up.[19] Babies with large livers, bone damage and skin lesions suggestive of congenital syphilis also require testing.[19]

Tests may include dark field microscopy.[3] Serological testing is carried out on the mother and the baby; venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests.[3] If the neonatal IgG antibody titres are significantly higher than the mother's, then congenital syphilis can be confirmed. Specific IgM in the infant is another method of confirmation. CSF pleocytosis, raised CSF protein level and positive CSF serology suggest neurosyphilis.[20]

-

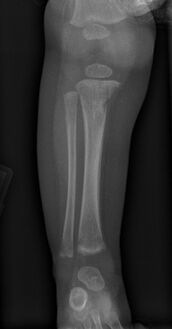

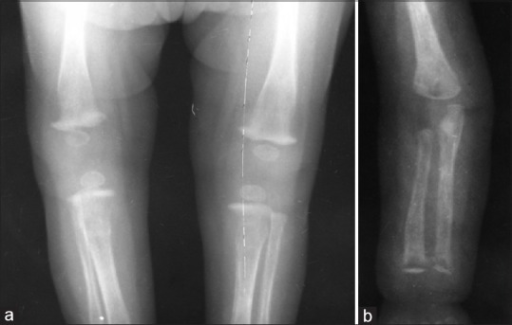

Wimberger corner sign; X-rays of (a) lower limbs (AP view) and (b) upper limbs (AP view) showing resolution of metaphyseal erosions and periosteal reaction

-

a) X-ray of the lower limb (AP view) showing proximal tibial metaphyseal erosions along with periosteal reaction and (b) X-ray of the upper limb (AP view) showing distal tibial and fibular metaphyseal erosions with periosteal reaction

-

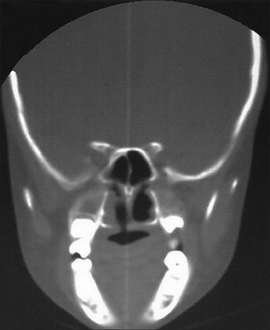

CT PNS showing the bilateral maxillary and nasal polyps

-

CT PNS showing the perforation of right side of hard palate

Prevention

Prevention is by safe sex to prevent syphilis in the mother, and early screening and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy.[5][11] One intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin G (2.4MIU) administered to a pregnant woman early in the illness can prevent congenital syphilis in her baby.[11]

Treatment

Treatment of suspected congenital syphilis is with penicillin by injection; benzylpenicillin into vein (50,000 units/kg twice daily during the first 7 days of life and three times daily thereafter for a total of 10 days), or procaine benzylpenicillin into muscle (50,000 units/kg in a single daily dose for 10 days) or benzathine penicillin G into muscle (50,000 units/kg in a single dose).[6][10] During times of penicillin unavailability, ceftriaxone may be used.[10] Where there is penicillin allergy, antimicrobial desensitisation may be considered.[10][12]

Epidemiology

Syphilis affects around one million pregnancies a year.[13] In 2016, there were around 473 cases of congenital syphilis per 100,000 live births and 204,000 deaths from the disease worldwide.[7] Of the 660,000 congenital syphilis cases reported in 2016, 143,000 resulted in deaths of unborn babies, 61,000 deaths of newborn babies, 41,000 low birth weights or preterm births, and 109,000 young children diagnosed with congenital syphilis.[14] Around 75% were from the WHO's African and Eastern Mediterranean regions.[4]

History

The origin of syphilis is unclear.[21] The disease was first described in children in the sixteenth century, and thought to be due to breastfeeding.[16] Nineteenth century physicans believed that congenital syphilis was acquired from semen ("semen inheritance") at the time of conception, and the unborn baby then transmitted it to the mother via the placenta.[17] This false theory was used to explain why the mother was typically without symptoms until after childbirth.[17] Then, the condition was popularly known as the "snuffles".[22] Serological tests for syphilis were introduced in 1906, and it was later shown that transmission occurred from the mother.[17]

-

Gérard de Lairesse, Dutch Baroque painter who suffered from congenital syphilis.

-

Inheritance by Edvard Munch (1899)

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 Medoro, Alexandra K.; Sánchez, Pablo J. (June 2021). "Syphilis in Neonates and Infants". Clinics in Perinatology. 48 (2): 293–309. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2021.03.005. ISSN 1557-9840. PMID 34030815. Archived from the original on 2022-07-20. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Ghanem, Khalil G.; Hook, Edward W. (2020). "303. Syphilis". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 1986. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Congenital Syphilis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 April 2021. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Adamson, Paul C.; Klausner, Jeffrey D. (2022). "60. Syphilis (Treponema palladium)". In Jong, Elaine C.; Stevens, Dennis L. (eds.). Netter's Infectious Diseases (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 339–347. ISBN 978-0-323-71159-3. Archived from the original on 2023-07-06. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "STD Facts - Congenital Syphilis". www.cdc.gov. 10 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Ferri, Fred F. (2022). "Syphilis". Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2022. Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 1452–1454. ISBN 978-0-323-75571-9. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021 (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization;. 2021. ISBN 978-92-4-003098-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-26. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "18. Syphilis, Yaws, Bejel, and Pinta". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. pp. 347–361. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

- ↑ Gilmour, Leeyan S.; Walls, Tony (15 March 2023). "Congenital Syphilis: a Review of Global Epidemiology". Clinical Microbiology Reviews: e0012622. doi:10.1128/cmr.00126-22. ISSN 1098-6618. PMID 36920205. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 "Congenital Syphilis - STI Treatment Guidelines". www.cdc.gov. 19 October 2022. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 WHO guideline on syphilis screening and treatment for pregnant women. Geneva: World health Organization. 2017. ISBN 978-92-4-155009-3. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chastain, DB; Hutzley, VJ; Parekh, J; Alegro, JVG (9 August 2019). "Antimicrobial Desensitization: A Review of Published Protocols". Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland). 7 (3). doi:10.3390/pharmacy7030112. PMID 31405062. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hussain, Syed A.; Vaidya, Ruben (2023). "Congenital Syphilis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725772. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Congenital syphilis - Mother-to-child transmission of syphilis". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ Akhtar, F; Rehman, S (16 January 2018). "Prevention of Congenital Syphilis Through Antenatal Screenings in Lusaka, Zambia: A Systematic Review". Cureus. 10 (1): e2078. doi:10.7759/cureus.2078. PMID 29560291. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Nissanka-Jayasuriya, EH; Odell, EW; Phillips, C (September 2016). "Dental Stigmata of Congenital Syphilis: A Historic Review With Present Day Relevance". Head and neck pathology. 10 (3): 327–31. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0703-z. PMID 26897633. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Oriel, J. David (2012). "5. "The sins of the fathers": Congenital syphilis". The Scars of Venus: A History of Venereology. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-1-4471-2068-1. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ↑ "Congenital Syphilis". University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on 2019-05-14. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 David, Marion; Hcini, Najeh; Mandelbrot, Laurent; Sibiude, Jeanne; Picone, Olivier (May 2022). "Fetal and neonatal abnormalities due to congenital syphilis: A literature review". Prenatal Diagnosis. 42 (5): 643–655. doi:10.1002/pd.6135. ISSN 1097-0223. Archived from the original on 2022-08-02. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- ↑ South, Mike (2012). Practical Paediatrics (7th ed.). Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. pp. 368, 830. ISBN 9780702042928.

- ↑ Harper, Kristin N.; Zuckerman, Molly K.; Harper, Megan L.; Kingston, John D.; Armelagos, George J. (2011). "The origin and antiquity of syphilis revisited: An Appraisal of Old World pre-Columbian evidence for treponemal infection". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 146 (S53): 99–133. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21613. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- ↑ Holmes, Timothy (1889). "20. venereal diseases". A Treatise on Surgery: Its Principles and Practice (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co. pp. 437–438. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |