Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

| Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Janz syndrome | |

| |

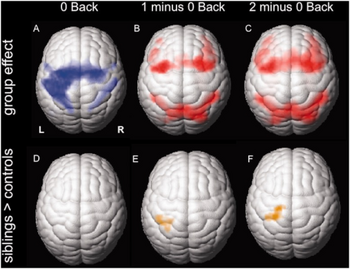

| Group functional MRI activation maps from juvenile myoclonic epilepsy individual(s) a-c) Cortical activation for the three different task conditions d-f) activation patterns in unaffected juvenile myoclonic epilepsy siblings compared to controls | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), also known as Janz syndrome, is a fairly common form of generalized epilepsy of presumed genetic origin (previously known an idiopathic generalized epilepsy),[1] and is also known as “Castels and Mendilaharsu Syndrome” in South America,[2] representing 5-10% of all epilepsy cases.[3][4][5] This disorder typically first manifests itself between the ages of 12 and 18 with sudden brief involuntary single or multiple episodes of muscle(s) contractions caused by an abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.[2] These events typically occur either early in the morning or upon sleep deprivation. JME reported as inherited idiopathic epilepsy syndrome (generalized).[6]

Additional clinical presentations include seizures with either a motor (tonic-clonic seizure) or nonmotor (absence seizure) generalized onset.[7] The evidence of absence seizure is very rare in the patient with JME.[6] Genetic studies have demonstrated several loci for JME and identified mutations in 4 genes.[8]

Signs and symptoms

The characteristic signs of JME are brief episodes of involuntary muscle twitching. These are brief episodes of involuntary muscle contractions occurring early in the morning or shortly before falling asleep. They are more common in the arms than in the legs and may result in dropping objects. Myoclonic jerks may as well appear in clusters. Other seizure types include those with either motor or non motor generalized onset. The onset of symptoms is generally around age 10-16 although some patients can present in their 20s or even early 30s. The myoclonic jerks generally precede the generalized tonic-clonic seizures by several months. Sleep deprivation is a major factor in triggering seizures in JME patients.[7]

Cause

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy is an inherited genetic syndrome, but the way in which this disorder is inherited is unclear. Frequently (17-49%) those with JME have relatives with a history of epileptic seizures. There is also a higher rate of females showing JME symptoms than males.[4] The majority of JME cases have an onset in early childhood to puberty.[3] The six genes BRD2, CASR, GABRA1, GABRD, EFHC1, and ICK are considered major vulnerable alleles for JME.[2]

Pathophysiology

CACNB4

CACNB4 is a gene that encodes the calcium channel β subunit protein. β subunits are important regulators of calcium channel current amplitude, voltage dependence, and also regulate channel trafficking.[9] In mice, a naturally occurring null mutation leads to the "lethargic" phenotype. This is characterized by ataxia and lethargic behavior at early stages of development followed within days by the onset of both focal motor seizures as well as episodes of behavioral immobility which correlates with patterns of cortical spike and wave discharges at the EEG[10] A premature-termination mutation R482X was identified in a patient with JME while an additional missense mutation C104F was identified in a German family with generalized epilepsy and praxis – induced seizures.[11]

The R482X mutation results in increased current amplitudes and an accelerated fast time constant of inactivation.[12] Whether these modest functional differences may be in charge of JME remains to be established.[12] Calcium channel β4 subunit (CACNB4) is not strictly considered a putative JME gene because its mutation did not segregate in affected family members, and it was found in only one member of a JME family from Germany, and it has not been replicated.[13]

GABRA1

GABRA1 is a gene that encodes for an α subunit of the GABA A receptor protein, which encodes one of the major inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors. There is one known mutation in this gene that is associated with JME, A322D, which is located in the third segment of the protein[14]/sub>. This missense mutation results in channels with reduced peak GABA-evoked currents.[15] Furthermore, the presence of such mutation alters the composition and reduces the expression of wild-type GABAA receptors.[15]

GABRD

GABRD encodes the δ subunit of the GABA receptor, which is an important constituent of the GABAA receptor mediating tonic inhibition in neurons (extrasynaptic GABA receptors, i.e. receptors that are localized outside of the synapse).[16] Among the mutations that have been reported in this in this gene, one (R220H) has been identified in a small family with JME. This mutation affects GABAergic transmission by altering the surface expression of the receptor as well as reducing the channel – opening duration.

Myoclonin1/EFHC1

The final known associated gene is EFHC1. Myoclonin1/EFHC1 encodes for a protein that has been known to play a wide range ofwild-typeom cell division, neuroblast migration and synapse/dendrite formation. EFHC1 is expressed in many tissues, including the brain, where it is localized to the soma and dendrites of neurons, particularly the hippocampal CA1 region, pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex, and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum.[17]

There are four JME-causing mutations discovered (D210N, R221H, F229L and D253Y). The mutations do not seem to alter the ability of the protein to colocalize with centrosomes and mitotic spindles but induce mitotic spindle defects. Moreover, the mutations impact radial and tangential migration during brain development.[17] As such a theory has been put forward that JME may be the result of a brain developmental disorder.[17]

Other loci

Three SNP alleles in BRD2, Cx-36 and ME2 and microdeletions in 15q13.3, 15q11.2 and 16p.13.11 also contribute risk to JME.[8]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically made based on patient history. The physical examination is usually normal. The primary diagnosis for JME is a good knowledge of patient history and the neurologist's familiarity with the myoclonic jerks, which are the hallmark of the syndrome.[18] Additionally, an electroencephalogram (EEG), will indicate a characteristic pattern of waves and spikes associated with the syndrome such as generalized 4–6 Hz polyspike and slow wave discharges. These discharges may be evoked by photic stimulation (blinking lights) and/or hyperventilation.

Both a magnetic resonance imaging scan (MRI) and computed tomography scan (CT scan) generally appear normal in JME patients. However a number of quantitative MRI studies have reported focal or regional abnormalities of the subcortical and cortical grey matter, particularly the thalamus and frontal cortex, in JME patients.[19] Positron emission tomography reports in some patients may indicate local deviations in many transmitter systems.[20]

Management

The most effective anti-epileptic medication for JME is valproic acid (Depakote).[21][22]

Due to valproic acid's high incidence of fetal malformations,[23][21] women of child-bearing age are started on alternative medications such as Lamotrigine, levetiracetam. Carbamazepine may aggravate genetic generalized epilepsies and as such its use should be avoided in JME. Treatment is lifelong. However, recent follow-up researches on a subgroup of patients showed them becoming seizure-free and off anti-epileptic drugs in due course of time.[24][25][26] This makes this dogma questionable. Patients should be warned to avoid sleep deprivation.

History

The first citation of JME was made in 1857 when Théodore Herpin described a 13-year-old boy suffering from myoclonic jerks, which progressed to tonic-clonic seizures three months later.[27] In 1957, Janz and Christian published a journal article describing several patients with JME.[28] The name Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy was proposed in 1975 and adopted by the International League Against Epilepsy.[27]

Culture

Stand-up comedian Maisie Adam has JME and her award-winning show "Vague" (2018) discussed it.[29]

The 2018 documentary film Separating The Strains dealt with the use of CBD oil to treat symptoms of JME.[30] Currently, no scientific evidence exist to support the use of CBD oil to treat symptoms of JME.

See also

References

- ↑ Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, Connolly MB, French J, Guilhoto L, et al. (April 2017). "ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology". Epilepsia. 58 (4): 512–521. doi:10.1111/epi.13709. PMC 5386840. PMID 28276062.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Gilsoul M, Grisar T, Delgado-Escueta AV, de Nijs L, Lakaye B (2019). "Subtle Brain Developmental Abnormalities in the Pathogenesis of Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 13: 433. doi:10.3389/fncel.2019.00433. PMC 6776584. PMID 31611775.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Panayiotopoulos CP, Obeid T, Tahan AR (1994). "Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a 5-year prospective study". Epilepsia. 35 (2): 285–296. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02432.x. PMID 8156946. S2CID 2840926.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Camfield CS, Striano P, Camfield PR (July 2013). "Epidemiology of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy". Epilepsy & Behavior. 28 (Suppl 1): S15–S17. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.06.024. PMID 23756473. S2CID 27904623.

- ↑ Syvertsen M, Hellum MK, Hansen G, Edland A, Nakken KO, Selmer KK, Koht J (January 2017). "Prevalence of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy in people <30 years of age-A population-based study in Norway". Epilepsia. 58 (1): 105–112. doi:10.1111/epi.13613. PMID 27861775. S2CID 46366621.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wandschneider B, Centeno M, Vollmar C, Symms M, Thompson PJ, Duncan JS, Koepp MJ (September 2014). "Motor co-activation in siblings of patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: an imaging endophenotype?". Brain. 137 (Pt 9): 2469–2479. doi:10.1093/brain/awu175. PMC 4132647. PMID 25001494.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité DG, de Weerd A, Beniczky S (July 2013). "Chronodependency and provocative factors in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy". Epilepsy & Behavior. 28 (Suppl 1): S25–S29. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.11.045. PMID 23756476. S2CID 40326663.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Delgado-Escueta AV, Koeleman BP, Bailey JN, Medina MT, Durón RM (July 2013). "The quest for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy genes". Epilepsy & Behavior. 28 (Suppl 1): S52–S57. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.06.033. PMID 23756480. S2CID 1159871.

- ↑ Buraei Z, Yang J (October 2010). "The ß subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels". Physiological Reviews. 90 (4): 1461–1506. doi:10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. PMC 4353500. PMID 20959621.

- ↑ Burgess DL, Jones JM, Meisler MH, Noebels JL (February 1997). "Mutation of the Ca2+ channel beta subunit gene Cchb4 is associated with ataxia and seizures in the lethargic (lh) mouse". Cell. 88 (3): 385–392. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81877-2. PMID 9039265.

- ↑ Escayg A, De Waard M, Lee DD, Bichet D, Wolf P, Mayer T, et al. (May 2000). "Coding and noncoding variation of the human calcium-channel beta4-subunit gene CACNB4 in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and episodic ataxia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (5): 1531–1539. doi:10.1086/302909. PMC 1378014. PMID 10762541.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Etemad S, Campiglio M, Obermair GJ, Flucher BE (2014). "The juvenile myoclonic epilepsy mutant of the calcium channel β(4) subunit displays normal nuclear targeting in nerve and muscle cells". Channels. 8 (4): 334–343. doi:10.4161/chan.29322. PMC 4203735. PMID 24875574.

- ↑ Delgado-Escueta AV (2007). "Advances in genetics of juvenile myoclonic epilepsies". Epilepsy Currents. 7 (3): 61–67. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2007.00171.x. PMC 1874323. PMID 17520076.

- ↑ Cossette P, Liu L, Brisebois K, Dong H, Lortie A, Vanasse M, et al. (June 2002). "Mutation of GABRA1 in an autosomal dominant form of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy". Nature Genetics. 31 (2): 184–189. doi:10.1038/ng885. PMID 11992121. S2CID 11974933.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Macdonald RL, Kang JQ, Gallagher MJ (2012). "GABAA Receptor Subunit Mutations and Genetic Epilepsies". In Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV (eds.). Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet] (4th ed.). National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). PMID 22787601. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ Hirose S (2014). "Mutant GABAA receptor subunits in genetic (Idiopathic) epilepsy". Mutant GABA(A) receptor subunits in genetic (idiopathic) epilepsy. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 213. pp. 55–85. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63326-2.00003-X. ISBN 9780444633262. PMID 25194483.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 de Nijs L, Wolkoff N, Coumans B, Delgado-Escueta AV, Grisar T, Lakaye B (December 2012). "Mutations of EFHC1, linked to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, disrupt radial and tangential migrations during brain development". Human Molecular Genetics. 21 (23): 5106–5117. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds356. PMC 3490517. PMID 22926142.

- ↑ Grünewald RA, Chroni E, Panayiotopoulos CP (June 1992). "Delayed diagnosis of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 55 (6): 497–499. doi:10.1136/jnnp.55.6.497. PMC 1014908. PMID 1619419.

- ↑ Kim JH (December 2017). "Grey and White Matter Alterations in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Review". Journal of Epilepsy Research. 7 (2): 77–88. doi:10.14581/jer.17013. PMC 5767493. PMID 29344465.

- ↑ Koepp MJ, Woermann F, Savic I, Wandschneider B (July 2013). "Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy--neuroimaging findings". Epilepsy & Behavior. Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy: What is it Really?. 28 (Suppl 1): S40–S44. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.06.035. PMID 23756478. S2CID 21360686.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Tomson T, Battino D, Perucca E (February 2016). "Valproic acid after five decades of use in epilepsy: time to reconsider the indications of a time-honoured drug". The Lancet. Neurology. 15 (2): 210–218. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00314-2. PMID 26655849. S2CID 29434414.

- ↑ Yacubian EM (January 2017). "Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: Challenges on its 60th anniversary". Seizure. 44: 48–52. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2016.09.005. PMID 27665373. S2CID 4930675.

- ↑ Tomson T, Marson A, Boon P, Canevini MP, Covanis A, Gaily E, et al. (July 2015). "Valproate in the treatment of epilepsy in girls and women of childbearing potential". Epilepsia. 56 (7): 1006–1019. doi:10.1111/epi.13021. PMID 25851171.

- ↑ Baykan B, Altindag EA, Bebek N, Ozturk AY, Aslantas B, Gurses C, et al. (May 2008). "Myoclonic seizures subside in the fourth decade in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy". Neurology. 70 (22 Pt 2): 2123–2129. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000313148.34629.1d. PMID 18505992. S2CID 28743237.

- ↑ Geithner J, Schneider F, Wang Z, Berneiser J, Herzer R, Kessler C, Runge U (August 2012). "Predictors for long-term seizure outcome in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: 25-63 years of follow-up". Epilepsia. 53 (8): 1379–1386. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03526.x. PMID 22686598. S2CID 13521080.

- ↑ Syvertsen MR, Thuve S, Stordrange BS, Brodtkorb E (May 2014). "Clinical heterogeneity of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: follow-up after an interval of more than 20 years". Seizure. 23 (5): 344–348. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2014.01.012. PMID 24512779. S2CID 14722826.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy at eMedicine

- ↑ Janz D, Christian W (1994). "Impulsive petit mal". In Malafosse A (ed.). Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsies: Clinical, Experimental and Genetic Aspects. pp. 229–51. ISBN 978-0-86196-436-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ "Comedian Maisie Adam shares her experiences growing up with epilepsy in her new show Vague Epilepsy Action". www.epilepsy.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ "Cannabis documentary about epilepsy to foster more understanding". 2018-06-13. Archived from the original on 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2022-04-26.