Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy

| Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: | |

| |

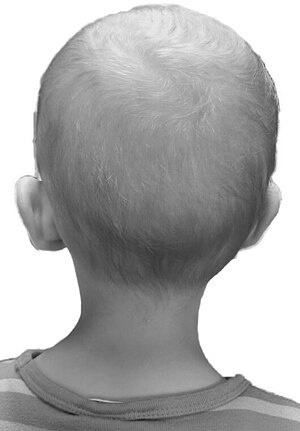

| Hypotrichosis (sparse hair growth) in a 5-year-old boy with HJMD | |

Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy (HJMD or CDH3) is an extremely rare congenital disease characterized by sparse hair growth (hypotrichosis) from birth and progressive macular corneal dystrophy.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of this condition is as follows:[2]

- Blindness

- Macular dystrophy

- Pili torti

- Sparse hair

Hair growth on the head is noticeably less full than normal, and the hairs are very weak; the rest of the body shows normal hair. The macular degeneration comes on slowly with deterioration of central vision, leading to a loss of reading ability. Those affected may otherwise develop in a completely healthy manner; life expectancy is normal.[citation needed]

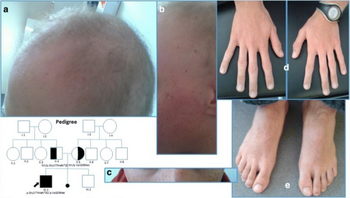

Cause

Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease.[3] It is caused by a combination of mutations (compound heterozygosity) in the CDH3 gene, which codes for Cadherin-3 (also known as P-Cadherin), a calcium-binding protein that is responsible for cellular adhesion in various tissues.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

The markedly anomalous hair growth should lead to a retinal examination by school entry at the latest, since weak vision will not necessarily be detected in the course of normal medical check-ups. Confirmation of a diagnosis, which is necessary for any future therapeutic options, is only possible by means of a molecular genetic diagnosis in the context of genetic counseling.[citation needed]

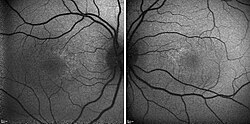

Examination method

The extent of retinal damage is assessed by fluorescent angiography, retinal scanning and optical coherence tomography; electrophysiological examinations such as electroretinography (ERG) or multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) may also be used.[citation needed]

-

Fluorescent angiogram of a 5-year-old boy with HJMD

-

Optical coherence tomography of a 5-year-old boy with HJMD

-

Fundoscopy, left eye of a 5-year-old boy with HJMD

-

Fundoscopy, right eye of a 5-year-old boy with HJMD

Differential diagnosis

Anomalies of the hair shaft caused by ectodermal dysplasia should be ruled out. Mutations in the CDH3 gene can also appear in EEM syndrome.

Treatment

There is no treatment for the disorder. A number of studies are looking at gene therapy, exon skipping and CRISPR interference to offer hope for the future. Accurate determination through confirmed diagnosis of the genetic mutation that has occurred also offers potential approaches beyond gene replacement for a specific group, namely in the case of diagnosis of a so-called nonsense mutation, a mutation where a stop codon is produced by the changing of a single base in the DNA sequence. This results in premature termination of protein biosynthesis, resulting in a shortened and either functionless or function-impaired protein. In what is sometimes called "read-through therapy", translational skipping of the stop codon, resulting in a functional protein, can be induced by the introduction of specific substances. However, this approach is only conceivable in the case of narrowly circumscribed mutations, which cause differing diseases.[citation needed]

Life planning

A disease that threatens the eyesight and additionally produces a hair anomaly that is apparent to strangers causes harm beyond the physical. It is therefore not surprising that learning the diagnosis is a shock to the patient. This is as true of the affected children as of their parents and relatives. They are confronted with a statement that there are at present no treatment options. They probably have never felt so alone and abandoned in their lives. The question comes to mind, "Why me/my child?" However, there is always hope and especially for affected children, the first priority should be a happy childhood. Too many examinations and doctor appointments take up time and cannot practically solve the problem of a genetic mutation within a few months. It is therefore advisable for parents to treat their child with empathy, but to raise him or her to be independent and self-confident by the teenage years. Openness about the disease and talking with those affected about their experiences, even though its rarity makes it unlikely that others will be personally affected by it, will together assist in managing life.

Epidemiology

It is estimated to affect less than one in a million people.[3] Only 50 to 100 cases have so far been described.[3]

History

The disease was first described in 1935 by Hans Wagner, a German physician.[4]

References

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular degeneration". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ "Juvenile macular degeneration and hypotrichosis | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Hypotrichose - juvenile Makuladegeneration: ORPHA1573". Orphanet (in German). Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2016-08-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Wagner, H. (1935). "Maculaaffektion, vergesellschaftet mit Haarabnormitat von Lanugotypus, beide vielleicht angeboren bei zwei Geschwistern". Graefes Archiv Klinischer und Experimenteller Ophthalalmologie (in German). 134: 74–81. doi:10.1007/BF01854763. S2CID 21073109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

Sources

- "A Rare Syndrome: Hypotrichosis with Juvenile Macular Dystrophy (HJMD)". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 55 (13): 6424. April 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): CADHERIN 3 - 114021

- Samuelov, L; Sprecher, E; Tsuruta, D; Bíró, T; Kloepper, J. E.; Paus, R (2012). "P-cadherin regulates human hair growth and cycling via canonical Wnt signaling and transforming growth factor-β2". Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 132 (10): 2332–41. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.171. PMID 22696062.

- Nagel-Wolfrum, K; Möller, F; Penner, I; Wolfrum, U (2014). "Translational read-through as an alternative approach for ocular gene therapy of retinal dystrophies caused by in-frame nonsense mutations". Visual Neuroscience. 31 (4–5): 309–16. doi:10.1017/S0952523814000194. PMID 24912600. (Review).

- Gregory-Evans, C. Y.; Wang, X; Wasan, K. M.; Zhao, J; Metcalfe, A. L.; Gregory-Evans, K (2014). "Postnatal manipulation of Pax6 dosage reverses congenital tissue malformation defects". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124 (1): 111–116. doi:10.1172/JCI70462. PMC 3871240. PMID 24355924.

- Schwarz, N.; Carr, A.-J.; Lane, A.; Moeller, F.; Chen, L. L.; Aguila, M.; Nommiste, B.; Muthiah, M. N.; Kanuga, N.; Wolfrum, U.; Nagel-Wolfrum, K.; Da Cruz, L.; Coffey, P. J.; Cheetham, M. E.; Hardcastle, A. J. (2014). "Translational read-through of the RP2 Arg120stop mutation in patient iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelium cells". Human Molecular Genetics. 24 (4): 972–86. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu509. PMC 4986549. PMID 25292197.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |