Hydranencephaly

| Hydranencephaly Hydrancephaly | |

|---|---|

| |

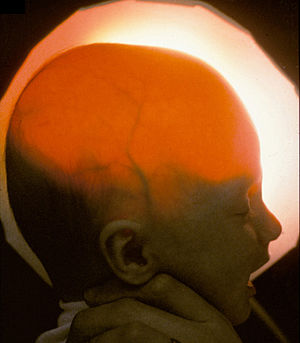

| Light passing through the skull of a hydranencephalic baby, underscoring the absence of the forebrain — Image courtesy of D. P. Agamanolis | |

Hydranencephaly[1] is a condition in which the brain's cerebral hemispheres are absent to a great degree and the remaining cranial cavity is filled with cerebrospinal fluid.[2] "Cephalic" is the scientific term for "head" or "head end of body".

Hydranencephaly[3] is a type of cephalic disorder. These disorders are congenital conditions that derive from damage to, or abnormal development of, the fetal nervous system in the earliest stages of development in utero. These conditions do not have any definitive identifiable cause factor. Instead, they are generally attributed to a variety of hereditary or genetic conditions, but also by environmental factors such as maternal infection, pharmaceutical intake, or even exposure to high levels of radiation.[4]

Hydranencephaly should not be confused with hydrocephalus, which is an accumulation of excess cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles of the brain.

In hemihydranencephaly, only half of the cranial cavity is affected.[5]

Signs and symptoms

An infant with hydranencephaly may appear normal at birth or may have some distortion of the skull and upper facial features due to fluid pressure inside the skull. The infant's head size and spontaneous reflexes such as sucking, swallowing, crying, and moving the arms and legs may all seem normal, depending on the severity of the condition. However, after a few weeks the infant sometimes becomes irritable and has increased muscle tone (hypertonia). After several months of life, seizures and hydrocephalus may develop, if they did not exist at birth. Other symptoms may include visual impairment, lack of growth, deafness, blindness, spastic quadriparesis (paralysis), and intellectual deficits.[citation needed]

Some infants may have additional abnormalities at birth including seizures, myoclonus (involuntary sudden, rapid jerks), limited thermoregulation abilities, and respiratory problems. Still other infants display no obvious symptoms at birth, going many months without a confirmed diagnosis of hydranencephaly. In some cases severe hydrocephalus, or another cephalic condition, is misdiagnosed.[citation needed]

Causes

Hydranencephaly is an extreme form of porencephaly, which is characterized by a cyst or cavity in the cerebral hemispheres.[citation needed]

Although the exact cause of hydranencephaly remains undetermined in most cases, the most likely general cause is by vascular insult, such as stroke, injury, intrauterine infections, or traumatic disorders after the first trimester of pregnancy. In a number of cases where intrauterine infection was determined to be the causing factor, most involved toxoplasmosis and viral infections such as enterovirus, adenovirus, parvovirus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, Epstein-Barr, and syncytial viruses. Another cause factor is monochorionic twin pregnancies, involving the death of one twin in the second trimester, which in turn causes vascular exchange to the living twin through placental circulation through twin-to-twin transfusion, causing hydranencephaly in the surviving fetus.[6] One medical journal reports hydranencephaly as an autosomal inherited disorder with an unknown mode of transmission, causing a blockage of the carotid artery where it enters the cranium; this causes obstruction and damage to the cerebral cortex.[3]

Genetic

Hydranencephaly is a recessive genetic condition, so both parents must carry the asymptomatic gene and pass it along to their child. There is a 25% chance that both parents will pass the gene to their child, resulting in hydranencephaly. Genetic hydranencephaly afflicts both males and females in equal numbers.[citation needed]

Post-natal brain injury

Though hydranencephaly is typically a congenital disorder, it can occur as a postnatal diagnosis in the aftermath of meningitis, intracerebral infarction, ischemia, or a traumatic brain injury.[7]

Diagnosis

An accurate, confirmed diagnosis is generally impossible until after birth, though prenatal diagnosis using fetal ultrasonography (ultrasound) can identify characteristic physical abnormalities. After birth, diagnosis may be delayed for several months because the infant's early behavior appears to be relatively normal. The most accurate diagnostic techniques are thorough clinical evaluation (considering physical findings and a detailed patient history); advanced imaging techniques, such as angiography, computerized tomography (CT scan), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); and (more rarely) transillumination.[3] However, diagnostic literature fails to provide a clear distinction between severe obstructive hydrocephalus and hydranencephaly, leaving some children with an unsettled diagnosis.[7]

Preliminary diagnosis may be made in utero via standard ultrasound, and can be confirmed with a standard anatomy ultrasound. Hydranencephaly is sometimes misdiagnosed as bilaterally symmetric schizencephaly (a less destructive developmental process on the brain), severe hydrocephalus (cerebrospinal fluid excess within the skull), or alobar holoprosencephaly (a neurological developmental anomaly).

Once destruction of the brain is complete, the cerebellum, midbrain, thalami, basal ganglia, choroid plexus, and portions of the occipital lobes typically remain preserved to varying degrees. The cerebral cortex is absent; however, in most cases, the fetal head remains enlarged due to increased intracranial pressure, which results from inadequate reabsorption of the cerebrospinal fluid produced in the choroid plexus.[6]

Prognosis

There is no standard treatment for hydranencephaly. Treatment is symptomatic and supportive. An accompanying diagnosis of hydrocephalus may be treated with surgical insertion of a shunt; this often improves prognosis and quality of life.[8]

The prognosis for children with hydranencephaly is generally quite poor. Death often occurs within the first year of life,[9] though many children live several years, or even into adulthood; in one reported case, a woman with hydranencephaly was assessed at age 32.[10]

Occurrence

This condition affects under 1 in 10,000 births worldwide.[6] Hydranencephaly is a rare disorder in the United States, which is defined as affecting fewer than 1 in 250,000.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Kandel, Eric R. (2013). Principles of neural science (5. ed.). Appleton and Lange: McGraw Hill. p. 1020. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ↑ "Hydranencephaly: Definition, Information, Diagnosis & Prognosis". 29 September 2012. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 National Organization for Rare Disorders. "Hydranencephaly". Rare Diseases Information.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ National Institute of Neurological Conditions and Stroke, NINDS. "Hydranencephaly Information Page". Disorders. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ Ulmer S, Moeller F, Brockmann MA, Kuhtz-Buschbeck JP, Stephani U, Jansen O (2005). "Living a normal life with the nondominant hemisphere: magnetic resonance imaging findings and clinical outcome for a patient with left-hemispheric hydranencephaly". Pediatrics. 116 (1): 242–5. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0425. PMID 15995064. S2CID 45671819.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Kurtz & Johnson, Alfred & Pamela. "Case Number 7: Hydranencephaly". Radiology, 210, 419-422. Archived from the original on 2013-03-27. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dubey, AK Lt Col. "Is it Hydranencephaly-A Variant?" (PDF). MJAFI 2002; 58:338-339. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-02.

- ↑ "Everything Guide to Children with Hydranencephaly" by Brayden Alexander Global Foundation for Hydranencephaly, Incorporated.

- ↑ McAbee GN, Chan A, Erde EL (2000). "Prolonged survival with hydranencephaly: report of two patients and literature review" (PDF). Pediatr. Neurol. 23 (1): 80–4. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(00)00154-5. PMID 10963978. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-14. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ S. A. Counter (Dec 15, 2007). "Preservation of brainstem neurophysiological function in hydranencephaly". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 263 (1–2): 198–207. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.043. PMID 17719607. S2CID 26948761.

- ↑ Rare Disease Day: February 28. "What is a Rare Disease?". Rare Disease. Archived from the original on 2018-10-24.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from January 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2018

- Congenital disorders of nervous system

- Rare diseases