Hong Kong flu

| Influenza (Flu) |

|---|

|

The Hong Kong flu, also known as the 1968 flu pandemic, was a flu pandemic whose outbreak in 1968 and 1969 killed between one and four million people globally.[1][2][3][4][5] It is among the deadliest pandemics in history, and was caused by an H3N2 strain of the influenza A virus. The virus was descended from H2N2 (which caused the Asian flu pandemic in 1957–1958) through antigenic shift—a genetic process in which genes from multiple subtypes are reassorted to form a new virus.[6][7][8]

History

Origin and outbreak in Hong Kong and China

The first recorded instance of the outbreak appeared on 13 July 1968 in British Hong Kong.[8][10][11][12] There is an unconfirmed possibility that the outbreak actually began in Mainland China before it spread to Hong Kong.[11][13]

The outbreak in Hong Kong, where the population density was greater than 6,000 people per square kilometre (20,000 per sq. mi.), reached its maximum intensity in two weeks.[11][12] The outbreak lasted around six weeks, affecting about 15% of the population (some 500,000 people infected), but the mortality rate was low and the clinical symptoms were mild.[11][12][14][15]

There were two waves of the flu in mainland China, one between July–September in 1968 and the other between June–December in 1970.[15] The reported data were very limited due to the Cultural Revolution, but retrospective analysis of flu activity between 1968–1992 shows that flu infection was the most serious in 1968, implying that most areas in China were affected at the time.[15]

Outbreaks in other areas

By the end of July 1968, extensive outbreaks were reported in Vietnam and Singapore.[12] Despite the lethality of the 1957 Asian Flu in China, little improvement had been made regarding the handling of such epidemics.[12] The Times was the first source to report the new possible pandemic.[12]

By September 1968, the flu had reached India, the Philippines, northern Australia, and Europe. The same month, the virus entered California and was carried by troops returning from the Vietnam War, but it did not become widespread in the United States until December 1968. It reached Japan, Africa, and South America by 1969.[16] At the time of the outbreak, the Hong Kong flu was also known as the "Mao flu" or "Mao Tse-tung flu".[17][18][19][20]

Worldwide deaths from the virus peaked in December 1968 and January 1969, when public health warnings[21] and virus descriptions[22] had been widely issued in the scientific and medical journals. In Berlin, the excessive number of deaths led to corpses being stored in subway tunnels, and in West Germany, garbage collectors had to bury the dead because of a lack of undertakers. In total, East and West Germany registered 60,000 estimated deaths. In some areas of France, half of the workforce was bedridden, and manufacturing suffered large disruptions because of absenteeism. The UK postal and rail services were also severely disrupted.[23]

Vaccine and aftermath

Four months into the Hong Kong flu pandemic, American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman and his team had created a vaccine and more than 9 million doses had been manufactured.[24][25] The same team also played a key role in developing a vaccine during the 1957–58 Asian flu pandemic.[25][26]

The H3N2 virus returned during the following 1969–70 flu season, which resulted in a second, deadlier wave of deaths in Europe, Japan, and Australia.[27] It remains in circulation today as a strain of seasonal flu.[2]

Clinical data

Flu symptoms typically lasted four to five days, but some cases persisted for up to two weeks.[16]

Virology

The Hong Kong flu was the first known outbreak of the H3N2 strain, but there is serologic evidence of H3N1 infections in the late 19th century. The virus was isolated in Queen Mary Hospital.[28]

The H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic flu strains both contained genes from avian influenza viruses. The new subtypes arose in pigs coinfected with avian and human viruses and were soon transferred to humans. Swine were considered the original "intermediate host" for influenza because they supported reassortment of divergent subtypes. However, other hosts appear capable of similar coinfection (such as many poultry species), and direct transmission of avian viruses to humans is possible. H1N1, associated with the 1918 flu pandemic, may have been transmitted directly from birds to humans.[29]

The Hong Kong flu strain shared internal genes and the neuraminidase with the 1957 Asian flu (H2N2). Accumulated antibodies to the neuraminidase or internal proteins may have resulted in many fewer casualties than most other pandemics. However, cross-immunity within and between subtypes of influenza is poorly understood.[citation needed]

The basic reproduction number of the flu in this period was estimated at 1.80.[30]

-

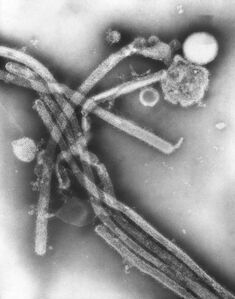

This negatively-stained transmission electron microscopic (TEM) image revealed the presence of a number of Hong Kong Flu virus virions, the H3N2 subtype of the Influenza A virus. Note the proteinaceous coat, or capsid, surrounding each virion, and the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase spikes, which differ in terms of their molecular make-up from strain to strain.

-

The influenza viruses that caused the Hong Kong flu (magnified approximately 100,000 times)

Mortality

The estimates of the total death toll due to Hong Kong flu (from its beginning in July 1968 until the outbreak faded during the winter of 1969–70[31]) vary:

- The World Health Organization and Encyclopaedia Britannica estimated the number of deaths due to Hong Kong flu to be between 1 and 4 million globally.[1][17]

- The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that, in total, the virus caused the deaths of 1 million people worldwide.[32]

However, the death rate from the Hong Kong flu was lower than most other 20th-century pandemics.[16] The World Health Organization estimated the case fatality rate of Hong Kong flu to be lower than 0.2%.[1] The disease was allowed to spread through the population without restrictions on economic activity, and a vaccine created by American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman and his team became available four months after it had started.[23][24][25] Fewer people died during this pandemic than in previous pandemics for several reasons:[32]

- Some immunity against the N2 flu virus may have been retained in populations struck by the Asian Flu strains that had been circulating since 1957.

- The pandemic did not gain momentum until near the winter school holidays in the Northern Hemisphere, thus limiting the infection's spread.

- Improved medical care gave vital support to the very ill.

- The availability of antibiotics that were more effective against secondary bacterial infections.

By region

For this pandemic, there were two geographically-distinct mortality patterns. In North America (the United States and Canada), the first pandemic season (1968/69) was more severe than the second (1969/70). In the "smoldering" pattern seen in Europe and Asia (United Kingdom, France, Japan, and Australia), the second pandemic season was two to five times more severe than the first.[27] The United States health authorities estimated that about 34,000[33][34] to 100,000[32] people died in the U.S; most excess deaths were in those aged 65 and older.[35]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Pandemic Influenza Risk Management: WHO Interim Guidance" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rogers, Kara (25 February 2010). "1968 flu pandemic". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Open Publishing. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ Paul, William E. (2008). Fundamental Immunology. p. 1273. ISBN 9780781765190. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ "World health group issues alert Mexican president tries to isolate those with swine flu". Associated Press. 25 April 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ↑ Mandel, Michael (26 April 2009). "No need to panic... yet Ontario officials are worried swine flu could be pandemic, killing thousands". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ↑ "History's deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ "1968 Pandemic (H3N2 virus)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jester, Barbara J.; Uyeki, Timothy M.; Jernigan, Daniel B. (May 2020). "Fifty Years of Influenza A(H3N2) Following the Pandemic of 1968". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (5): 669–676. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305557. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 7144439. PMID 32267748.

- ↑ Morris, Denise E.; Cleary, David W.; Clarke, Stuart C. (23 June 2017). "Secondary Bacterial Infections Associated with Influenza Pandemics". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 1041. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01041. ISSN 1664-302X.

- ↑ "How 1968's deadly Hong Kong flu left more than one million dead". South China Morning Post. 13 July 2018. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Chang, W. K. (1969). "National Influenza Experience in Hong Kong, 1968" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. WHO. 41 (3): 349–351. PMC 2427693. PMID 5309438. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "Hong Kong Flu (1968 Influenza Pandemic)". Sino Biological. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ Cockburn, W. Charles (1969). "Origin and progress of the 1968-69 Hong Kong influenza epidemic". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3–4–5): 343–348. PMC 2427756. PMID 5309437.

- ↑ "How 1968's deadly Hong Kong flu left more than one million dead". South China Morning Post. 13 July 2018. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Qin, Ying; et al. (2018). "History of influenza pandemics in China during the past century". Chinese Journal of Epidemiology (in 中文). 39 (8): 1028–1031. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.003. PMID 30180422. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Starling, Arthur (2006). Plague, SARS, and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. HK University Press. p. 55. ISBN 962-209-805-3. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Honigsbaum, Mark (13 June 2020). "Revisiting the 1957 and 1968 influenza pandemics". The Lancet. 395 (10240): 1824–1826. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31201-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7247790. PMID 32464113.

- ↑ "200,000 in Rome Have Flu (Published 1968)". The New York Times. 3 November 1968. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ↑ "The crises of winters past". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ↑ "Desert Sun 28 May 1969 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ↑ Jones, F. Avery (1968), "Winter Epidemics", British Medical Journal, 1968 (4): 327, doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5626.327-c, PMC 1912285

- ↑ Coleman, Marion T.; Dowdle, Walter R.; Pereira, Helio G.; Schild, Geoffrey C.; Chang, W. K. (1968), "The Hong Kong/68 Influenza A2 Variant", The Lancet, 292 (7583): 1384–1386, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(68)92683-4, PMID 4177941

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Pancevski, Bojan (24 April 2020). "Forgotten Pandemic Offers Contrast to Today's Coronavirus Lockdowns". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Vaccine for Hong Kong Influenza Pandemic". History of Vaccines. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). "Maurice Hilleman: Creator of Vaccines That Changed the World". Case Studies in Public Health: 443–470. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00003-2. ISBN 9780128045718. PMC 7150172.

- ↑ "Confronting a Pandemic, 1957". The Scientist Magazine®. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Viboud, Cécile; Grais, Rebecca F.; Lafont, Bernard A. P.; Miller, Mark A.; Simonsen, Lone (15 July 2005). "Multinational Impact of the 1968 Hong Kong Influenza Pandemic: Evidence for a Smoldering Pandemic". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 192 (2): 233–248. doi:10.1086/431150. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 15962218. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ Peckham, Robert (November 2020). "Viral surveillance and the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemic". Journal of Global History. 15 (3): 444–458. doi:10.1017/S1740022820000224. ISSN 1740-0228. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ Belshe, R. B. (2005). "The origins of pandemic influenza – lessons from the 1918 virus". New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (21): 2209–2211. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058281. PMID 16306515. Cited in Harder, Timm C.; Werner, Ortrud. Kamps, Bernd Sebastain; Hoffmann, Christian; Preiser, Wolfgang (eds.). "Influenza Report". Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- ↑ Biggerstaff, M.; Cauchemez, S.; Reed, C.; et al. (2014). "Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature". BMC Infectious Diseases. 14 (480): 480. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-480. PMC 4169819. PMID 25186370.

- ↑ Dutton, Gail (13 April 2020). "The 1968 Pandemic Strain (H3N2) Persists. Will COVID-19?". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "1968 Pandemic (H3N2 virus)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ↑ "Pandemics and Pandemic Threats since 1900". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 31 March 2009.

- ↑ "1968 Hong Kong flu – CDC". Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ Shiel, William. "Medical Definition of Hong Kong flu". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

External links

- Influenza Research Database – Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- CS1 中文-language sources (zh)

- EngvarB from January 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Use dmy dates from January 2020

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2020

- 1968 in Hong Kong

- Health in Hong Kong

- Influenza pandemics

- 1968 health disasters

- 20th-century epidemics