History of polio

The history of polio (poliomyelitis) infections began during prehistory. Although major polio epidemics were unknown before the 20th century,[1] the disease has caused paralysis and death for much of human history. Over millennia, polio survived quietly as an endemic pathogen until the 1900s when major epidemics began to occur in Europe.[1] Soon after, widespread epidemics appeared in the rest of the world. By 1910, frequent epidemics became regular events throughout the developed world primarily in cities during the summer months. At its peak in the 1940s and 1950s, polio would paralyze or kill over half a million people worldwide every year.[2]

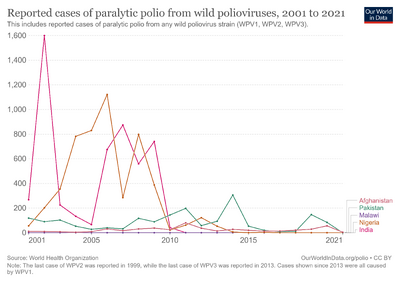

The fear and the collective response to these epidemics would give rise to extraordinary public reaction and mobilization spurring the development of new methods to prevent and treat the disease and revolutionizing medical philanthropy. Although the development of two polio vaccines has eliminated wild poliomyelitis in all but two countries (Afghanistan and Pakistan),[3][4] the legacy of poliomyelitis remains in the development of modern rehabilitation therapy and in the rise of disability rights movements worldwide.

Early history

Ancient Egyptian paintings and carvings depict otherwise healthy people with withered limbs, and children walking with canes at a young age.[5] It is theorized that the Roman Emperor Claudius was stricken as a child, and this caused him to walk with a limp for the rest of his life.[6] Perhaps the earliest recorded case of poliomyelitis is that of Sir Walter Scott. In 1773, Scott was said to have developed "a severe teething fever which deprived him of the power of his right leg".[7] At the time, polio was not known to medicine. A retrospective diagnosis of polio is considered to be strong due to the detailed account Scott later made,[8] and the resultant lameness of his right leg had an important effect on his life and writing.[9]

The symptoms of poliomyelitis have been described by many names. In the early nineteenth century the disease was known variously as: Dental Paralysis, Infantile Spinal Paralysis, Essential Paralysis of Children, Regressive Paralysis, Myelitis of the Anterior Horns, Tephromyelitis (from the Greek tephros, meaning "ash-gray") and Paralysis of the Morning.[10] In 1789 the first clinical description of poliomyelitis was provided by the British physician Michael Underwood—he refers to polio as "a debility of the lower extremities".[11] The first medical report on poliomyelitis was by Jakob Heine, in 1840; he called the disease Lähmungszustände der unteren Extremitäten ("Paralysis of the lower Extremities").[12] Karl Oskar Medin was the first to empirically study a poliomyelitis epidemic in 1890.[13] This work, and the prior classification by Heine, led to the disease being known as Heine-Medin disease.

Epidemics

Major polio epidemics were unknown before the 20th century; localized paralytic polio epidemics began to appear in Europe and the United States around 1900.[1] The first report of multiple polio cases was published in 1843 and described an 1841 outbreak in Louisiana. A fifty-year gap occurs before the next U.S. report—a cluster of 26 cases in Boston in 1893.[1] The first recognized U.S. polio epidemic occurred the following year in Vermont with 132 total cases (18 deaths), including several cases in adults.[13] Numerous epidemics of varying magnitude began to appear throughout the country; by 1907 approximately 2,500 cases of poliomyelitis were reported in New York City.[14]

Richard Rhodes, A Hole in the World

On Saturday, June 17, 1916, an official announcement of the existence of an epidemic polio infection was made in Brooklyn, New York. That year, there were 27,363 cases and 7,130 deaths due to polio in the United States, with over 2,000 deaths in New York City alone.[16][17] The names and addresses of individuals with confirmed polio cases were published daily in the press, their houses were identified with placards, and their families were quarantined.[18] Dr. Hiram M. Hiller, Jr. was one of the physicians in several cities who realized what they were dealing with, but the nature of the disease remained largely a mystery. The 1916 epidemic caused widespread panic and thousands fled the city to nearby mountain resorts; movie theaters were closed, meetings were canceled, public gatherings were almost nonexistent, and children were warned not to drink from water fountains, and told to avoid amusement parks, swimming pools, and beaches.[17] From 1916 onward, a polio epidemic appeared each summer in at least one part of the country, with the most serious occurring in the 1940s and 1950s.[1] In the epidemic of 1949, 42,173 cases were reported in the United States and 2,720 deaths from the disease occurred. Canada and the United Kingdom were also affected.[19][20]

Prior to the 20th century, polio infections were rarely seen in infants before 6 months of age, and most cases occurred in children 6 months to 4 years of age.[21] Young children who contract polio generally develop only mild symptoms, but as a result they become permanently immune to the disease.[22] In developed countries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, improvements were being made in community sanitation, including improved sewage disposal and clean water supplies. Better hygiene meant that infants and young children had fewer opportunities to encounter and develop immunity to polio. Exposure to poliovirus was therefore delayed until late childhood or adult life, when it was more likely to take the paralytic form.[21]

In children, paralysis due to polio occurs in one in 1,000 cases, while in adults, paralysis occurs in one in 75 cases.[23] By 1950, the peak age incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis in the United States had shifted from infants to children aged 5 to 9 years; about one-third of the cases were reported in persons over 15 years of age.[24] Accordingly, the rate of paralysis and death due to polio infection also increased during this time.[1] In the United States, the 1952 polio epidemic was the worst outbreak in the nation's history, and is credited with heightening parents' fears of the disease and focusing public awareness on the need for a vaccine.[25] Of the 57,628 cases reported that year, 3,145 died and 21,269 were left with mild to disabling paralysis.[25][26]

Historical treatments

In the early 20th century—in the absence of proven treatments—a number of odd and potentially dangerous polio treatments were suggested. In John Haven Emerson's A Monograph on the Epidemic of Poliomyelitis (Infantile Paralysis) in New York City in 1916[27] one suggested remedy reads:

Give oxygen through the lower extremities, by positive electricity. Frequent baths using almond meal, or oxidising the water. Applications of poultices of Roman chamomile, slippery elm, arnica, mustard, cantharis, amygdalae dulcis oil, and of special merit, spikenard oil and Xanthoxolinum. Internally use caffeine, Fl. Kola, dry muriate of quinine, elixir of cinchone, radium water, chloride of gold, liquor calcis and wine of pepsin.[28]

Following the 1916 epidemics and having experienced little success in treating polio patients, researchers set out to find new and better treatments for the disease. Between 1917 and the early 1950s, several therapies were explored in an effort to prevent deformities, including hydrotherapy and electrotherapy.[citation needed]

In 1939, Albert Sabin reported that "In the experiments reported in the present communication it was found that vitamin C, both natural and synthetic preparations, had no effect on the course of experimental poliomyelitis induced by nasal instillation of the virus."[29][30]

Surgical treatments such as nerve grafting, tendon lengthening, tendon transfers, and limb lengthening and shortening were used extensively during this time.[31][32] Patients with residual paralysis were treated with braces and taught to compensate for lost function with the help of calipers, crutches and wheelchairs. The use of devices such as rigid braces and body casts, which tended to cause muscle atrophy due to the limited movement of the user, were also touted as effective treatments.[33] Massage and passive motion exercises were also used to treat patients with polio.[32] Most of these treatments proved to be of little therapeutic value, however several effective supportive measures for the treatment of polio did emerge during these decades including the iron lung, an anti-polio antibody serum, and a treatment regimen developed by Sister Elizabeth Kenny.[34]

Iron lung

The first iron lung used in the treatment of polio was invented by Philip Drinker, Louis Agassiz Shaw, and James Wilson at Harvard, and tested October 12, 1928, at Children's Hospital, Boston.[35] The original Drinker iron lung was powered by an electric motor attached to two vacuum cleaners, and worked by changing the pressure inside the machine. When the pressure is lowered, the chest cavity expands, trying to fill this partial vacuum. When the pressure is raised the chest cavity contracts. This expansion and contraction mimics the physiology of normal breathing. The design of the iron lung was subsequently improved by using a bellows attached directly to the machine, and John Haven Emerson modified the design to make production less expensive.[35] The Emerson Iron Lung was produced until 1970.[36] Other respiratory aids were used, such as the Bragg-Paul Pulsator and the "rocking bed" for patients with less critical breathing difficulties.[37]

During the polio epidemics, the iron lung saved many thousands of lives, but the machine was large, cumbersome and very expensive:[38] in the 1930s, an iron lung cost about $1,500—about the same price as the average home.[39] The cost of running the machine was also prohibitive, as patients were encased in the metal chambers for months, years and sometimes for life.[36] Even with an iron lung, the fatality rate for patients with bulbar polio exceeded 90%.[40]

These drawbacks led to the development of more modern positive-pressure ventilators and the use of positive-pressure ventilation by tracheostomy. Positive pressure ventilators reduced mortality in bulbar patients from 90% to 20%.[41] In the Copenhagen epidemic of 1952, large numbers of patients were ventilated by hand ("bagged") by medical students and anyone else on hand because of the large number of bulbar polio patients and the small number of ventilators available.[42]

Passive immunotherapy

In 1950 William Hammon at the University of Pittsburgh isolated serum, containing antibodies against poliovirus, from the blood of polio survivors.[34] The serum, Hammon believed, would prevent the spread of polio and to reduce the severity of disease in polio patients.[43] Between September 1951 and July 1952 nearly 55,000 children were involved in a clinical trial of the anti-polio serum.[44] The results of the trial were promising; the serum was shown to be about 80% effective in preventing the development of paralytic poliomyelitis, and protection was shown to last for 5 weeks if given under tightly controlled circumstances.[45] The serum was also shown to reduce the severity of the disease in patients who developed polio.[34]

The large-scale use of antibody serum to prevent and treat polio had a number of drawbacks, however, including the observation that the immunity provided by the serum did not last long, and the protection offered by the antibody was incomplete, that re-injection was required during each epidemic outbreak, and that the optimal time frame for administration was unknown.[43] The antibody serum was widely administered, but obtaining the serum was an expensive and time-consuming process, and the focus of the medical community soon shifted to the development of a polio vaccine.[46]

Kenny regimen

Early management practices for paralyzed muscles emphasized the need to rest the affected muscles and suggested that the application of splints would prevent tightening of muscle, tendons, ligaments, or skin that would prevent normal movement. Many paralyzed polio patients lay in plaster body casts for months at a time. This prolonged casting often resulted in atrophy of both affected and unaffected muscles.[5]

In 1940, Sister Elizabeth Kenny, an Australian bush nurse from Queensland, arrived in North America and challenged this approach to treatment. In treating polio cases in rural Australia between 1928 and 1940, Kenny had developed a form of physical therapy that—instead of immobilizing affected limbs—aimed to relieve pain and spasms in polio patients through the use of hot, moist packs to relieve muscle spasm and early activity and exercise to maximize the strength of unaffected muscle fibers and promote the neuroplastic recruitment of remaining nerve cells that had not been killed by the virus.[33] Sister Kenny later settled in Minnesota where she established the Sister Kenny Rehabilitation Institute, beginning a world-wide crusade to advocate her system of treatment. Slowly, Kenny's ideas won acceptance, and by the mid-20th century had become the hallmark for the treatment of paralytic polio.[31] In combination with antispasmodic medications to reduce muscular contractions, Kenny's therapy is still used in the treatment of paralytic poliomyelitis.

In 2009 as part of the Q150 celebrations, the Kenny regimen for polio treatment was announced as one of the Q150 Icons of Queensland for its role as an iconic "innovation and invention".[47]

Vaccine development

In 1935 Maurice Brodie, a research assistant at New York University and William Hallock Park of the New York City Department of Health, attempted to produce a polio vaccine, procured from virus in ground up monkey spinal cords, and killed by formaldehyde. Brodie first tested the vaccine on himself and several of his assistants. He then gave the vaccine to three thousand children. Many developed allergic reactions, but none of the children developed an immunity to polio.[48] During the late 1940s and early 1950s, a research group, headed by John Enders at the Boston Children's Hospital, successfully cultivated the poliovirus in human tissue. This significant breakthrough ultimately allowed for the development of the polio vaccines. Enders and his colleagues, Thomas H. Weller and Frederick C. Robbins, were recognized for their labors with the Nobel Prize in 1954.[49]

Two vaccines are used throughout the world to combat polio. The first was developed by Jonas Salk, first tested in 1952 using the HeLa cell, and announced to the world by Salk on April 12, 1955.[46] The Salk vaccine, or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), consists of an injected dose of killed poliovirus. In 1954, the vaccine was tested for its ability to prevent polio; its field trials grew to be the largest medical experiment in history. In 1955, it was chosen for use throughout the United States. By 1957, following mass immunizations promoted by the March of Dimes, the annual number of polio cases in the United States was reduced, from a peak of nearly 58,000 cases, to 5,600 cases.[13]

Eight years after Salk's success, Albert Sabin developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using live but weakened (attenuated) virus.[50] Human trials of Sabin's vaccine began in 1957 and it was licensed in 1962. Following the development of oral polio vaccine, a second wave of mass immunizations led to a further decline in the number of cases: by 1961, only 161 cases were recorded in the United States.[51] The last cases of paralytic poliomyelitis caused by endemic transmission of poliovirus in the United States were in 1979, when an outbreak occurred among the Amish in several Midwestern states.[52]

Legacy

Early in the twentieth century polio became one of the most feared diseases of the developed world.[citation needed] The disease hit without warning and required long quarantine periods during which parents were separated from children: it was impossible to tell who would get the disease and who would be spared.[13] The consequences of the disease left polio survivors marked for life, leaving behind vivid images of wheelchairs, crutches, leg braces, breathing devices, and deformed limbs. However, polio changed not only the lives of those who survived it, but also affected profound cultural changes: the emergence of grassroots fund-raising campaigns that would revolutionize medical philanthropy, the rise of rehabilitation therapy and, through campaigns for the social and civil rights of disabled people, polio survivors helped to spur the modern disability rights movement.

In addition, the occurrence of polio epidemics led to a number of public health innovations. One of the most widespread was the proliferation of "no spitting" ordinances in the United States and elsewhere.[53]

Philanthropy

In 1921 Franklin D. Roosevelt became totally and permanently paralyzed from the waist down. Although the paralysis (whether from poliomyelitis, as diagnosed at the time, or from Guillain–Barré syndrome) had no cure at the time, Roosevelt, who had planned a life in politics, refused to accept the limitations of his disease. He tried a wide range of therapies, including hydrotherapy in Warm Springs, Georgia (see below). In 1938 Roosevelt helped to found the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now known as the March of Dimes), that raised money for the rehabilitation of people with paralytic polio, and was instrumental in funding the development of polio vaccines. The March of Dimes changed the way it approached fund-raising. Rather than soliciting large contributions from a few wealthy individuals, the March of Dimes sought small donations from millions of individuals. Its hugely successful fund-raising campaigns collected hundreds of millions of dollars—more than all of the U.S. charities at the time combined (with the exception of the Red Cross).[54] By 1955 the March of Dimes had invested $25.5 million in research;[55] funding both Jonas Salk's and Albert Sabin's vaccine development; the 1954–55 field trial of vaccine, and supplies of free vaccine for thousands of children.[39]

In 1952, during the worst recorded epidemic, 3,145 people in the United States died from polio.[56]

Rehabilitation therapy

Prior to the polio scares of the twentieth century, most rehabilitation therapy was focused on treating injured soldiers returning from war. The disabling effects of polio led to heightened awareness and public support of physical rehabilitation, and in response a number of rehabilitation centers specifically aimed at treating polio patients were opened, with the task of restoring and building their remaining strength and teaching new, compensatory skills to large numbers of newly paralyzed individuals.[38]

In 1926, Franklin Roosevelt, convinced of the benefits of hydrotherapy, bought a resort at Warm Springs, Georgia, where he founded the first modern rehabilitation center for treatment of polio patients which still operates as the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation.[57]

The cost of polio rehabilitation was often more than the average family could afford, and more than 80% of the nation's polio patients would receive funding through the March of Dimes.[54] Some families also received support through philanthropic organizations such as the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine fraternity, which established a network of pediatric hospitals in 1919, the Shriners Hospitals for Children, to provide care free of charge for children with polio.[58]

Disability rights movement

As thousands of polio survivors with varying degrees of paralysis left the rehabilitation hospitals and went home, to school and to work, many were frustrated by a lack of accessibility and discrimination they experienced in their communities. In the early twentieth century the use of a wheelchair at home or out in public was a daunting prospect as no public transportation system accommodated wheelchairs and most public buildings including schools, were inaccessible to those with disabilities. Many children left disabled by polio were forced to attend separate institutions for "crippled children" or had to be carried up and down stairs.[57]

As people who had been paralyzed by polio matured, they began to demand the right to participate in the mainstream of society. Polio survivors were often in the forefront of the disability rights movement that emerged in the United States during the 1970s, and pushed legislation such as the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 which protected qualified individuals from discrimination based on their disability, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[57][59] Other political movements led by polio survivors include the Independent Living and Universal design movements of the 1960s and 1970s.[60]

Polio survivors are one of the largest disabled groups in the world. The World Health Organization estimates that there are 10 to 20 million polio survivors worldwide.[61] In 1977, the National Health Interview Survey reported that there were 254,000 people living in the United States who had been paralyzed by polio.[62] According to local polio support groups and doctors, some 40,000 polio survivors with varying degrees of paralysis live in Germany, 30,000 in Japan, 24,000 in France, 16,000 in Australia, 12,000 in Canada and 12,000 in the United Kingdom.[61]

See also

- List of polio survivors

- Polio Hall of Fame

- Cutter Laboratories

- Hickory, North Carolina

- Polio eradication

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Trevelyan B, Smallman-Raynor M, Cliff A (2005). "The Spatial Dynamics of Poliomyelitis in the United States: From Epidemic Emergence to Vaccine-Induced Retreat, 1910–1971". Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 95 (2): 269–293. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00460.x. PMC 1473032. PMID 16741562.

- ↑ "What is Polio" (PDF). Canadian International Immunization Initiative. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ "Poliomyelitis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2017-04-18. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ↑ "Global polio eradication initiative applauds WHO African region for wild polio-free certification". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2020-08-27. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Daniel TM, Robbins FC, eds. (1997). "A history of poliomyelitis". Polio. Rochester, N.Y., USA: University of Rochester Press. pp. 5–22. ISBN 1-878822-90-X.

- ↑ Shell M (2005). "Hamlet's Pause". Stutter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 0-674-01937-7. Archived from the original on 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ↑ Collier, William Douglas (1872). A history of English literature, in a series of biographical sketches. Toronto: J. Campbell. p. 400. ISBN 0-665-26955-2.

- ↑ Cone TE (1973). "Was Sir Walter Scott's lameness caused by poliomyelitis?". Pediatrics. 51 (1): 35. doi:10.1542/peds.51.1.35. PMID 4567583. S2CID 245078983.

- ↑ Robertson, Fiona. "'Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies'". Otranto.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ↑ Gould T (1995). "Chapter One". A Summer Plague: Polio and its Survivors. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06292-3.

- ↑ Underwood M (1789). "Debility of the lower extremities". A treatise on the diseases of children. Vol. 2. London: J. Mathews. pp. 53–56. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ↑ Pearce J (2005). "Poliomyelitis (Heine-Medin disease)". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 76 (1): 128. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.028548. PMC 1739337. PMID 15608013. Archived from the original on 2008-09-17.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Sass EJ, Gottfried G, Sorem A, eds. (1996). Polio's legacy: an oral history. Washington, D.C: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-0144-8. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ Sachs B (1910). "Epidemic poliomyelitis; report on the New York epidemic of 1907 by the Collective investigation committee". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.

- ↑ Richard Rhodes (1990). A Hole in the World. Simon and Schuster.

- ↑ "Reported paralytic polio cases and deaths, United States, 1910 to 2019". ourworldindata.org. 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-07-20. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Melnick J (1 July 1996). "Current status of poliovirus infections". Clin Microbiol Rev. 9 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.3.293. PMC 172894. PMID 8809461. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- ↑ Risse GB (1988). Fee E, Fox DM (eds.). Epidemics and History: Ecological Perspectives. in AIDS: The Burden of History. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-06396-1.

- ↑ "Major U.S. Epidemics". infoplease.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-15. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ↑ "Polio epidemic strikes Northern Canada". CBC Canada. March 7, 1949. Archived from the original on 2008-06-18. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Robertson S (1993). "Module 6: Poliomyelitis" (PDF). The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2014-01-13.

- ↑ Yin-Murphy M, Almond JW (1996). "Picornaviruses". In Baron S, et al. (eds.). Picornaviruses: The Enteroviruses: Polioviruses in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. PMID 21413259. Archived from the original on 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Gawne AC, Halstead LS (1995). "Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiology and clinical management". Critical Reviews in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 7 (2): 147–88. doi:10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.v7.i2.40. Archived from the original on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ Melnick JL (1990). Poliomyelitis. In: Tropical and Geographical Medicine (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 558–76. ISBN 0-07-068328-X.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "History of Vaccines Website - Polio cases Surge". College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 3 November 2010. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ↑ Zamula, Evelyn (1991). "A New Challenge for Former Polio Patients". FDA Consumer. 25 (5). Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Emerson H (1977). A monograph on the epidemic of poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis). New York: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-09817-0.

- ↑ Gould T (1995). A summer plague: polio and its survivors. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-300-06292-3. Archived from the original on 2022-07-02. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ↑ Williams, G. (2013). Paralysed with Fear: the Story of Polio, Palgrave–Macmillan, Houndmills UK, ISBN 978 1 137 29975 8, p. 164: "This time, there was no diplomatic solution. Sabin published what he had found, namely that vitamin C had no protective effect whatsoever in monkeys infected with polio intranasally.79 In response, Jungeblut produced a further paper, still insisting that vitamin C protected against paralysis – and then quietly moved into researching leukaemia."

- ↑ Sabin, A.B. (1939). "Vitamin C in Relation to Experimental Poliomyelitis". J. Exp. Med. 69 (4): 507–16. doi:10.1084/jem.69.4.507. PMC 2133652. PMID 19870860.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Leboeuf C (1992). The late effects of Polio: Information For Health Care Providers. Commonwealth Department of Community Services and Health. ISBN 1-875412-05-0. Archived from the original on 2007-04-22. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Frauenthal HW, Van V, Manning J (1914). Manual of infantile paralysis, with modern methods of treatment. Pathology: p. 79-101. Philadelphia Davis. OCLC 2078290. Archived from the original on 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Oppewal S (1997). "Sister Elizabeth Kenny, an Australian nurse, and treatment of poliomyelitis victims". Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 29 (1): 83–7. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01145.x. PMID 9127546.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Hammon W (1955). "Passive immunization against poliomyelitis". Monogr Ser World Health Organ. 26: 357–70. PMID 14374581.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Branson RD (1998). "A Tribute to John H. Emerson. Jack Emerson: Notes on his life and contributions to respiratory care" (PDF). Respiratory Care. 43 (7): 567–71. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2007.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Nelson R (2004). "On Borrowed Time: The last iron lung users face a future without repair service". AARP Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Mehta, Sangeeta; Hill, Nicholas S (2001). "Noninvasive Ventilation". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 163 (2): 540–577. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.9906116. PMID 11179136. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Wilson D (2005). "Braces, wheelchairs, and iron lungs: the paralyzed body and the machinery of rehabilitation in the polio epidemics". J Med Humanit. 26 (2–3): 173–90. doi:10.1007/s10912-005-2917-z. PMID 15877198. S2CID 40057889.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Staff of the National Museum of American History, Behring Center. "Whatever Happened to Polio?". Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ West J (2005). "The physiological challenges of the 1952 Copenhagen poliomyelitis epidemic and a renaissance in clinical respiratory physiology". J Appl Physiol. 99 (2): 424–32. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00184.2005. PMC 1351016. PMID 16020437. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Goldberg A (2002). "Noninvasive mechanical ventilation at home: building upon the tradition". Chest. 121 (2): 321–4. doi:10.1378/chest.121.2.321. PMID 11834636. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- ↑ Wackers G (1994). "Theaters of truth and competence. Intermittent positive pressure respiration during the 1952 polio-epidemic in Copenhagen". Constructivist Medicine. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Rinaldo C (2005). "Passive Immunization Against Poliomyelitis: The Hammon Gamma Globulin Field Trials, 1951–1953". Am J Public Health. 95 (5): 790–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.040790. PMC 1449257. PMID 15855454.

- ↑ "Unsung Hero of the War on Polio" (PDF). Public Health Magazine. University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Hammon W, Coriell L, Ludwig E, et al. (1954). "Evaluation of Red Cross gamma globulin as a prophylactic agent for poliomyelitis. 5. Reanalysis of results based on laboratory-confirmed cases". J Am Med Assoc. 156 (1): 21–7. doi:10.1001/jama.1954.02950010023009. PMID 13183798.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Spice B (2005-04-04). "Tireless polio research effort bears fruit and indignation". The Salk vaccine: 50 years later- second of two parts. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Bligh, Anna (10 June 2009). "PREMIER UNVEILS QUEENSLAND'S 150 ICONS". Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Pearce J (2004). "Salk and Sabin: poliomyelitis immunisation". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 75 (11): 1552. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.028530. PMC 1738787. PMID 15489385. Archived from the original on 2008-02-04.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1954". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Sabin A, Ramos-Alvarez M, Alvarez-Amezquita J, et al. (1960). "Live, orally given poliovirus vaccine. Effects of rapid mass immunization on population under conditions of massive enteric infection with other viruses". JAMA. 173: 1521–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1960.03020320001001. PMID 14440553.

- ↑ Hinman A (1984). "Landmark perspective: Mass vaccination against polio". JAMA. 251 (22): 2994–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1984.03340460072029. PMID 6371280.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1997). "Follow-up on poliomyelitis--United States, Canada, Netherlands. 1979". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 46 (50): 1195–9. PMID 9414151. Archived from the original on 2017-06-25.

- ↑ See David M. Oshinsky, Polio: an American Story. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Oshinsky DM (2005). Polio: an American story. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515294-8.

- ↑ "FDR and Polio: Public Life, Private Pain". Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Archived from the original on 2010-03-24. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Dunn HL (1955). Vital Statistics of the United States (1952): Volume II, Mortality Data (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-11-13.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Gallagher HG (2002). "Disability Rights And Russia (speech)". The Review of Arts, Literature, Philosophy and the Humanities. XXXII (1). Archived from the original on 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Rackl L (2006-06-05). "Hospital marks 80 years of treating kids for free". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2012-11-03. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Morris RB, Morris JB, eds. (1996). Encyclopedia of American History. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-270055-3.

- ↑ Scalise K (1998). "New collection of original documents and histories unveils disability rights movement". University of California at Berkeley News Release. Archived from the original on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "After Effects of Polio Can Harm Survivors 40 Years Later". March of Dimes: News Desk. 2001. Archived from the original on 2014-12-25. Retrieved 2014-11-14.

- ↑ Frick N, Bruno R (1986). "Post-polio sequelae: physiological and psychological overview". Rehabil Lit. 47 (5–6): 106–11. PMID 3749588.

Further reading

- Maus RA (2006). Lucky One: Making It Past Polio and Despair. Anterior Publishing. ISBN 0-9776205-0-6. A memoir by a childhood survivor of polio.

- Oshinsky DM (2005). Polio: An American Story. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515294-8. Awarded the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for history.

- Paul JR (1971). A History of Poliomyelitis. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01324-8. OCLC 118817. Classic history.

- Shell M (2005). Polio and Its Aftermath: The Paralysis of Culture. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01315-8. Memoir, history, medicine.

- Wilson DJ (2005). Living with Polio: The Epidemic and Its Survivors. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-90103-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) A history of polio from accounts written by survivors. Limited preview available from Google Books.

External links

- A History of Polio (Poliomyelitis) Archived 2022-03-08 at the Wayback Machine—History of Vaccines, a project of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

- What ever happened to Polio? Archived 2007-06-07 at the Wayback Machine—An exhibit from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

- The Middle-Class Plague: Epidemic Polio and the Canadian State. Archived 2021-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- CBC Digital Archives - Polio: Combating the Crippler Archived 2021-08-15 at the Wayback Machine—Video and radio reports related to polio

- Poliovirus in New Zealand 1915–1997 Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Polio: A Virus' Struggle Archived 2007-10-16 at the Wayback Machine—an amusing yet educational graphic novella from the Science Creative Quarterly (in PDF format).

- Fermín: Making Polio History Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine—An article about Luis Fermín Tenorio Cortez, the last case of polio reported in the Americas.

- A UK Polio survivor[permanent dead link]—An account of John Prestwich who lived 50 years in an iron lung.

- Post-Polio Health International Archived 2021-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2018

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Webarchive template wayback links

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from March 2024

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- History of medicine

- Polio