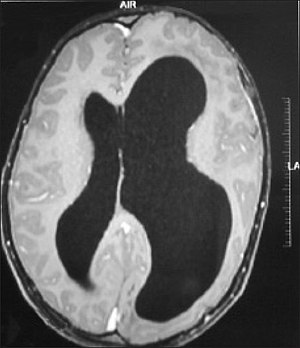

Hemimegalencephaly

| Hemimegalencephaly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Left-sided hemimegalencephaly in a person with neurofibromatosis[1] | |

| Symptoms | Frequent seizures often resistant to medicine |

| Usual onset | Congenital |

| Duration | Long term |

| Treatment | Hemispherectomy |

| Medication | Anti-epileptic drugs |

Hemimegalencephaly (HME), or unilateral megalencephaly, is a rare congenital disorder affecting all or a part of a cerebral hemisphere.[2] It causes severe seizures, which are often frequent and hard to control. A minority might have seizure control with medicines, but most will need removal or disconnection of the affected hemisphere as the best chance. Uncontrolled, they often cause progressive intellectual disability and brain damage and stop development.[3]

Symptoms and signs

Seizures are the main symptom. There can be as many as hundreds of seizures a day.[4] Seizures tend to begin soon after birth, but may sometimes commence during later infancy or, rarely, during early childhood.[5]

Other symptoms

- Asymmetrical or enlarged head[5]

- Developmental delay[5]

- Progressive weakness of half the body[5]

- Progressive blindness of half the body[5]

Genetics

Somatic activation of AKT3 causes hemispheric developmental brain malformations.[6]

Pathophysiology

It is a disorder related to excessive neuronal proliferation and hamartomatous overgrowth affecting the cortical formation.[7] The excessive proliferation is postulated to occur early and to possibly continue beyond the normal proliferative period. Epidermal growth factor is thought to play an important role in the excessive proliferation and the pathogenesis of HME.[8]

Diagnosis

It should be suspected in infants or children with intractable, frequent seizures.[4] On a CT scan, the affected part is distorted and enlarged.[9] It can be diagnosed prenatally, but a lot of cases go undiagnosed until seizures begin. Ultrasound can display asymmetrical brain hemispheres.[5]

Treatment

Although there have been a few reports of medical treatment, the main treatment is radical: remove or disconnect the affected side. However, it has a high mortality, and there have been reports of a vegetative state and seizures resuming, this time in the healthy hemisphere.[10]

Surgery should be done as early as possible to minimize damage caused by seizures. However, a trial with drugs can be attempted for a few months before surgery, and there is a slim chance of it succeeding.[10] The earlier surgery be done, the more the remaining side will do the missing side's job.[citation needed]

Benzodiazepines might control the seizures.[11]

References

- ↑ Acharya N, Reddy MS, Paulson CT, Prasanna D (January 2014). "Cranio-orbital-temporal neurofibromatosis: an uncommon subtype of neurofibromatosis type-1". Oman Journal of Ophthalmology. 7 (1): 43–5. doi:10.4103/0974-620X.127934. PMC 4008903. PMID 24799805.

- ↑ Sato, N; Yagishita, A; Oba, H; Miki, Y; Nakata, Y; Yamashita, F; Nemoto, K; Sugai, K; Sasaki, M (April 2007). "Hemimegalencephaly: a study of abnormalities occurring outside the involved hemisphere". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 28 (4): 678–82. PMID 17416820. Archived from the original on 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- ↑ "Hemimegalencephaly - Why hemispherectomy is usually required". www.brainrecoveryproject.org. Archived from the original on 2018-04-20. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Gene Mutations Cause Massive Brain Asymmetry". UC Health - UC San Diego. Archived from the original on 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 "Hemimegalencephaly & Cortical Dysplasia". hemifoundation.homestead.com. Archived from the original on 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- ↑ Poduri, Annapurna; Evrony, Gilad D.; Cai, Xuyu; Elhosary, Princess Christina; Beroukhim, Rameen; Lehtinen, Maria K.; Hills, L. Benjamin; Heinzen, Erin L.; Hill, Anthony; Hill, R. Sean; Barry, Brenda J.; Bourgeois, Blaise F.D.; Riviello, James J.; Barkovich, A. James; Black, Peter M.; Ligon, Keith L.; Walsh, Christopher A. (April 2012). "Somatic Activation of AKT3 Causes Hemispheric Developmental Brain Malformations". Neuron. 74 (1): 41–48. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.010. PMC 3460551. PMID 22500628.

- ↑ Abdel Razek, A.A.K.; Kandell, A.Y.; Elsorogy, L.G.; Elmongy, A.; Basett, A.A. (7 August 2008). "Disorders of Cortical Formation: MR Imaging Features". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 30 (1): 4–11. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A1223. PMC 7051699. PMID 18687750.

- ↑ Harvey B. Sarnat; Paolo Curatolo (26 September 2007). Malformations of the Nervous System. Newnes. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-08-055984-1. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ↑ Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (2012-06-15). "Radical surgery offers hope for baby racked by seizures". latimes.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bonioli, Eugenio; Palmieri, Antonella; Bellini, Carlo (1994-03-01). "Surgical vs. medical treatment of seizures in hemimegalencephaly". Brain and Development. 16 (2): 169. doi:10.1016/0387-7604(94)90060-4. ISSN 0387-7604. PMID 8048711. S2CID 2442788. Archived from the original on 2020-12-28. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- ↑ Trounce, J. Q.; Rutter, N.; Mellor, D. H. (1991). "Hemimegalencephaly: diagnosis and treatment. - Semantic Scholar". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 33 (3): 261–6. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1991.tb05116.x. PMID 1902803. S2CID 45836490. Archived from the original on 2018-06-15. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |