Hallux rigidus

| Hallux rigidus | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Stiff big toe | |

| |

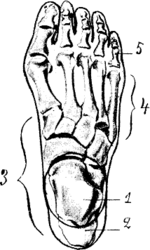

| Hallux not labeled but visible at upper left. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, Podiatry |

Hallux rigidus is arthritis in the big toe, which presents as pain and stiffness.[1]

Treatment is generally with better footwear and help from a podiatrist.[1] Another option is surgery.[1]

Signs and symptoms

- Pain and stiffness in the joint at the base of the big toe during use (walking, standing, bending, etc.)

- Difficulty with certain activities (running, squatting)

- Swelling and inflammation around the joint

Although the condition is degenerative, it can occur in patients who are relatively young, particularly active sports people who have at some time suffered trauma to the joint (turf toe). A notable example is NBA star Shaquille O'Neal[2] who returned to basketball after surgery.

Causes

This condition, which occurs in adolescents and adults, can be associated with previous trauma. The true cause is not known. Most commonly, hallux rigidus is thought to be caused by wear and tear of the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

Classification

In 1988, Hattrup and Johnson described the following radiographic classification system:

- Grade I – mild changes with maintained joint space and minimal spurring.

- Grade II – moderate changes with narrowing of joint space, bony proliferation on the metatarsophalangeal head and phalanx and subchondral sclerosis or cyst.

- Grade III – severe changes with significant joint space narrowing, extensive bony proliferation and loose bodies or a dorsal ossicle.[3]

Treatment

Non-surgical

Early treatment for mild cases of hallux rigidus may include prescription foot orthotics, shoe modifications (such as a pad under the joint, and/or a deeper toe box[4]to take the pressure off the toe and/or facilitate walking), specialized footwear ('rocker-sole' shoes), medications (anti-inflammatory drugs) or injection therapy (corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and pain). Physical therapy programs may be recommended, although there is very limited evidence that they provide benefit for reducing pain and improving function of the joint.[5]

Surgical

The goal of surgery is to eliminate or reduce pain. There are several types of surgery for treatment of hallux rigidus. The type of surgery is based on the stage of hallux rigidus. According to the Coughlin and Shurnas Clinical Radiographic Scale:[6]

Stage 1 hallux rigidus involves some loss of range of motion of the big toe joint or first MTP joint and is often treated conservatively with prescription foot orthotics.

Stage 2 hallux rigidus involves greater loss of range of motion and cartilage and may be treated via cheilectomy in which the metatarsal head is reshaped and bone spurs reduced.

Stage 3 hallux rigidus often involves significant cartilage loss and may be treated by an osteotomy in which cartilage on the first metatarsal head is repositioned, possibly coupled with a hemi-implant in which the base of the proximal phalanx (base of the big toe) is resurfaced.

Stage 4 hallux rigidus, also known as end stage hallux rigidus, involves severe loss of range of motion of the big toe joint and cartilage loss. Stage 4 hallux rigidus may be treated via fusion of the joint (arthrodesis) or implant arthroplasty in which both sides of the joint are resurfaced or a hinged implant is used. Fusion of the joint is often viewed as more definitive but may lead to significant alteration of gait causing postural symptomatology. The implants termed "two part unconstrained" implants in which a "ball" type device is placed on the first metatarsal head and "socket" portion on the base of the big toe do not have a good long term track record. The hinged implants have been in existence since the 1970s, have been continually improved and have the best record of improving long term function. Another example of MTP joint implant is "Roto-glide" which is designed to restore optimum anatomical movement whilst preserving as much primary bone stock as possible.[7] [8]

Cartilage replacement may be the first step before considering Fusion ( Arthrodesis- stiff toe joint) or arthroplasty. Cartilage repair for focal osteochondral defects of the first MTP may be a strategy before fusion or arthroplasty. Osteochondral plugs and resurfacing both have advocates. Although still at the case report stage, the experience is improving in the literature. [9]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Rahman, Anisur; Giles, Ian (2020). "18. Rheumatology". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ↑ Brown, Tim (12 September 2002). "Operation Goes Well on Shaq Toe". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Hattrup, SJ; Johnson, KA (1988). "Subjective results of hallux rigidus following treatment with cheilectomy". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. (226): 182–91. doi:10.1097/00003086-198801000-00025. PMID 3335093.

- ↑ Lam, A; Chan, JJ; Surace, MF; Vulcano, E (18 May 2017). "Hallux rigidus: How do I approach it?". World Journal of Orthopedics. 8 (5): 364–371. doi:10.5312/wjo.v8.i5.364. PMC 5434342. PMID 28567339.

- ↑ Zammit, Gerard V; Menz, Hylton B; Munteanu, Shannon E; Landorf, Karl B; Gilheany, Mark F (8 September 2010). "Interventions for treating osteoarthritis of the big toe joint". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD007809. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007809.pub2. PMID 20824867.

- ↑ Coughlin, MJ; Shurnas, PS (November 2003). "Hallux rigidus. Grading and long-term results of operative treatment". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 85 (11): 2072–88. doi:10.2106/00004623-200311000-00003. PMID 14630834.

- ↑ Kofoed, Hakon; Danborg, Lasse; Grindsted, Jacob; Merser, Soren (23 September 2017). "The Rotoglide™ total replacement of the first metatarso-phalangeal joint. A prospective series with 7-15 years clinico-radiological follow-up with survival analysis". Foot and Ankle Surgery. 23 (3): 148–152. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2017.04.004. PMID 28865581.

- ↑ Tunstall, Charlotte; Limaye, Rajiv; Laing, Patrick; Walker, Christopher; Kendall, S; LaValette, David; Mackenney, Paul; Adedapo, Akinwanda O; Al-Maiyah, Mohammed (September 2017). "1st metatarso-phalangeal joint arthroplasty with ROTO-glide implant". Foot and Ankle Surgery. 23 (3): 153–156. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2017.07.005. PMID 28865582.

- ↑ Van Dyke, B.; Berlet, G. C.; Daigre, J. L.; Hyer, C. F.; Philbin, T. M. (2018). "First Metatarsal Head Osteochondral Defect Treatment with Particulated Juvenile Cartilage Allograft Transplantation: A Case Series". Foot & Ankle International. 39 (2): 236–241. doi:10.1177/1071100717737482. PMID 29110501. S2CID 4220097. Archived from the original on 2021-10-05. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- rigidus and cheilectomy Hallux rigidus and cheilectomy at the Duke University Health System's Orthopedics program

- Overview at aaos.org Archived 2006-09-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Hallux Rigidus and Hallux Limitus – Classification and Treatment Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Diagram Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine