Goodpasture syndrome

| Goodpasture syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Goodpasture’s disease, antiglomerular basement antibody disease, anti-GBM disease | |

| |

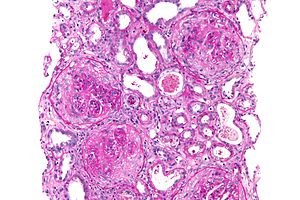

| Micrograph of a crescentic glomerulonephritis due to GPS, PAS stain | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

| Symptoms | blood in the urine, protein in the urine, coughing up blood[1] |

| Complications | Acute kidney failure[1] |

| Usual onset | ~25 years old[2] |

| Causes | Environmental trigger in those who are genetically susceptible[1] |

| Risk factors | HLA-DR15[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, kidney biopsy[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, lupus, microscopic polyangiitis, IgA nephropathy, acute glomerulonephritis[1] |

| Treatment | Corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis, hemodialysis, mechanical ventilation[1] |

| Prognosis | 5-year survival rate > 80% |

| Frequency | Rare[1] |

Goodpasture syndrome (GPS), also known as anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, is a disease that involves the kidneys and lungs.[1] Symptom may include blood in the urine, protein in the urine, and coughing up blood.[1] Shortness of breath, tiredness, and chest pain may also occur.[2] Acute kidney failure may result.[1]

It is believed to occur following an environmental trigger in people who are genetically susceptible.[1] Risk factors include HLA-DR15.[1] Triggers may include certain medications, cocaine, smoking, and infection by influenza.[1] The underlying mechanism involves autoantibodies against the basement membrane.[1] The diagnosis may be confirmed by blood testing looking for specific antibodies or a kidney biopsy.[1]

Treatment is generally with medications that suppress the immune system such as corticosteroids or cyclophosphamide.[1] Plasmapheresis may be done daily to remove antibodies from the blood.[1] Other required efforts may include hemodialysis or mechanical ventilation.[1] With treatment the 5-year survival rate is greater than 80% and less than 30% require long term dialysis.[1]

Goodpasture syndrome is a rare, affecting about one in a million people per year.[1] Males are more commonly affected than females.[2] Those around the age of 25 are most commonly affected.[2] It is named after the American pathologist Ernest Goodpasture who first described the condition in 1919.[1][3][4]

Signs and symptoms

The antiglomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies primarily attack the kidneys and lungs, although, generalized symptoms like malaise, weight loss, fatigue, fever, and chills are also common, as are joint aches and pains.[5] 60 to 80% of those with the condition experience both lung and kidney involvement; 20-40% have kidney involvement alone, and less than 10% have lung involvement alone.[5] Lung symptoms usually antedate kidney symptoms and usually include: coughing up blood, chest pain (in less than 50% of cases overall), cough, and shortness of breath.[6] Kidney symptoms usually include blood in the urine, protein in the urine, unexplained swelling of limbs or face, high amounts of urea in the blood, and high blood pressure.[5]

Cause

Its precise cause is unknown, but an insult to the blood vessels taking blood from and to the lungs is believed to be required to allow the anti-GBM antibodies to come into contact with the alveoli.[7] Examples of such an insult include:[7] exposure to organic solvents (e.g. chloroform) or hydrocarbons, exposure to tobacco smoke, certain alleles (HLA-DR15), infection (such as influenza A), cocaine inhalation, metal dust inhalation, bacteraemia, sepsis, high-oxygen environments, and treatment with antilymphocytic treatment (especially monoclonal antibodies).

Pathophysiology

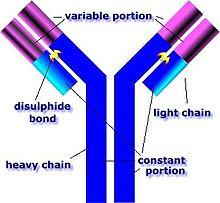

GPS is caused by abnormal plasma cell production of anti-GBM antibodies.[7] The anti-GBM antibodies attack the alveoli and glomeruli basement membranes.[7] These antibodies bind their reactive epitopes to the basement membranes and activate the complement cascade, leading to the death of tagged cells.[7] T cells are also implicated, though it is generally considered a type II hypersensitivity reaction.[7]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of GPS is often difficult, as numerous other diseases can cause the various manifestations of the condition and the condition itself is rare.[8] The most accurate means of achieving the diagnosis is testing the affected tissues by means of a biopsy, especially the kidney, as it is the best-studied organ for obtaining a sample for the presence of anti-GBM antibodies.[8] On top of the anti-GBM antibodies implicated in the disease, about one in three of those affected also has cytoplasmic antineutrophilic antibodies in their bloodstream, which often predates the anti-GBM antibodies by about a few months or even years.[8] The later the disease is diagnosed, the worse the outcome is for the affected person.[7]

Treatment

The major mainstay of treatment for GPS is plasmapheresis, a procedure in which the affected person's blood is sent through a centrifuge and the various components separated based on weight.[9] The plasma contains the anti-GBM antibodies that attack the affected person's lungs and kidneys, and is filtered out.[9] The other parts of the blood (the red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets) are recycled and intravenously reinfused.[9] Most individuals affected by the disease also need to be treated with immunosuppressant drugs, especially cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and rituximab, to prevent the formation of new anti-GBM antibodies so as to prevent further damage to the kidneys and lungs.[9] Other, less toxic immunosuppressants such as azathioprine may be used to maintain remission.[9]

Prognosis

With treatment, the five-year survival rate is >80% and fewer than 30% of affected individuals require long-term dialysis.[7] A study performed in Australia and New Zealand demonstrated that in patients requiring renal replacement therapy (including dialysis) the median survival time is 5.93 years.[7] Without treatment, virtually every affected person will die from either advanced kidney failure or lung hemorrhages.[7]

Epidemiology

GPS is rare, affecting about 0.5–1.8 per million people per year in Europe and Asia.[7] It is also unusual among autoimmune diseases in that it is more common in males than in females and is also less common in blacks than whites, but more common in the Māori people of New Zealand.[7] The peak age ranges for the onset of the disease are 20–30 and 60–70 years.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 DeVrieze, BW; Hurley, JA (January 2020). "Goodpasture Syndrome". PMID 29083697.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Goodpasture Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ Goodpasture EW (1919). "The significance of certain pulmonary lesions in relation to the etiology of influenza". Am J Med Sci. 158 (6): 863–870. doi:10.1097/00000441-191911000-00012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ↑ Salama AD, Levy JB, Lightstone L, Pusey CD (September 2001). "Goodpasture's disease". Lancet. 358 (9285): 917–920. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06077-9. PMID 11567730.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome Clinical Presentation". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ Schwarz, MI (November 2013). "Goodpasture Syndrome: Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage and Pulmonary-Renal Syndrome". Merck Manual Professional. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome Workup". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- GBM antibodies: immunofluorescence image Archived 2007-03-22 at the Wayback Machine