Ganado, Arizona

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

Ganado, Arizona | |

|---|---|

Location in Apache County and the state of Arizona | |

| Coordinates: 35°42′06″N 109°33′01″W / 35.70167°N 109.55028°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Apache |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.15 sq mi (23.70 km2) |

| • Land | 9.15 sq mi (23.69 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km2) |

| Elevation | 6,401 ft (1,951 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 883 |

| • Density | 96.54/sq mi (37.27/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| ZIP codes | 86505, 86540 |

| Area code | 928 |

| FIPS code | 04-26210 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2408273[2] |

Ganado (Navajo: Lókʼaahnteel) is a chapter of the Navajo Nation and census-designated place (CDP) in Apache County, Arizona, United States. The population was 1,210 at the 2010 census.[3]

Ganado is part of the Fort Defiance Agency, of the Bureau of Indian Affairs; and is the delegate seat for the district that encompasses the Jeddito, Cornfields, Ganado, Kinlichee, and Steamboat communities at the Navajo Nation Council. The Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site in Ganado is maintained as an example of a 19th-century trading post.

Geography

Ganado is located at 35°42′9″N 109°33′12″W / 35.70250°N 109.55333°W (35.702571, −109.553234).[4]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 9.2 square miles (23.7 km2), all land.[3] The greater Ganado area includes Ganado, Burnside, Cornfields, Kinlichee, Wood Springs, Klagetoh, and Steamboat and the family ranches dispersed amongst these sub-areas.

Climate

According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Ganado has a semi-arid climate, abbreviated "BSk" on climate maps.[5]

| Climate data for Ganado, Arizona, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1929–2016 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

72 (22) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

98 (37) |

101 (38) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

96 (36) |

92 (33) |

87 (31) |

73 (23) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.6 (13.7) |

61.3 (16.3) |

69.9 (21.1) |

77.1 (25.1) |

85.4 (29.7) |

93.6 (34.2) |

96.1 (35.6) |

93.3 (34.1) |

88.4 (31.3) |

80.4 (26.9) |

68.5 (20.3) |

58.9 (14.9) |

96.5 (35.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 44.2 (6.8) |

49.2 (9.6) |

57.5 (14.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

73.6 (23.1) |

85.3 (29.6) |

89.2 (31.8) |

86.5 (30.3) |

80.3 (26.8) |

68.7 (20.4) |

54.9 (12.7) |

44.5 (6.9) |

66.6 (19.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.0 (−0.6) |

34.8 (1.6) |

42.2 (5.7) |

48.1 (8.9) |

56.7 (13.7) |

66.9 (19.4) |

72.6 (22.6) |

71.2 (21.8) |

64.4 (18.0) |

51.7 (10.9) |

39.9 (4.4) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

50.9 (10.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 17.8 (−7.9) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

48.5 (9.2) |

56.0 (13.3) |

55.8 (13.2) |

48.4 (9.1) |

34.7 (1.5) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

35.2 (1.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1.9 (−16.7) |

4.4 (−15.3) |

12.3 (−10.9) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

27.6 (−2.4) |

36.2 (2.3) |

46.9 (8.3) |

49.0 (9.4) |

35.7 (2.1) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

9.8 (−12.3) |

0.2 (−17.7) |

−4.0 (−20.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−25 (−32) |

−9 (−23) |

5 (−15) |

15 (−9) |

27 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

35 (2) |

27 (−3) |

11 (−12) |

−16 (−27) |

−20 (−29) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.53 (13) |

0.67 (17) |

0.85 (22) |

0.64 (16) |

0.58 (15) |

0.23 (5.8) |

1.21 (31) |

1.75 (44) |

1.19 (30) |

0.93 (24) |

0.78 (20) |

0.77 (20) |

10.13 (257.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.0 (7.6) |

2.2 (5.6) |

2.4 (6.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.5 (3.8) |

3.3 (8.4) |

12.8 (32.52) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 37.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 5.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2 (mean maxima/minima, precip/precip days, snow/snow days 1981–2010)[7] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1,505 | — | |

| 2010 | 1,210 | −19.6% | |

| 2020 | 883 | −27.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] | |||

| Languages (2000)[9] | Percent |

|---|---|

| Spoke Navajo at home | 55% |

| Spoke English at home | 45% |

As of the census[10] of 2000, there were 1,505 people, 422 households, and 321 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 168.2 inhabitants per square mile (64.9/km2). There were 507 housing units at an average density of 56.6 per square mile (21.9/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 87.3% Native American, 10.8% White, 0.1% Black or African American, 0.1% Asian, 1.1% from other races, and 0.5% from two or more races. 2.4% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 422 households, out of which 46.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.3% were married couples living together, 21.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 23.7% were non-families. 21.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 3.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.5 and the average family size was 4.1.

In the CDP, the age distribution of the population shows 38.7% under the age of 18, 9.8% from 18 to 24, 26.6% from 25 to 44, 19.2% from 45 to 64, and 5.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 26 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.3 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $38,958, and the median income for a family was $43,281. Males had a median income of $36,250 versus $26,306 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $7,500. About 10.3% of families and 18.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.8% of those under age 18 and 37.8% of those age 65 or over.

History

Ancients and legends

The earliest peoples in the region are believed to have been nomadic hunters in search of big game roaming throughout the Four Corners region. The next wave of inhabitants are believed to have been smaller hunter-gatherer communities of similar nomadic characteristic. It is believed that archaic forms of agriculture came to the Little Colorado River basin around 1800 BCE.

The first permanent residents of the Ganado region (comprising greater Ganado, Kinlichee, Burnside, and Cornfields) were the "Basketmaker" Ancestral Puebloan. The ruins of their homesteads are scattered throughout the Little Colorado River basin and Colorado Plateau, among the red clay hills surrounding Ganado, and on the escarpment to the west. Significant agricultural advancement was seen in the first millennium. The largest Puebloan ruin at Ganado is Wide Reeds Ruin, along the floodplain near the present-day Ganado Wash bridge; and it is believed to have been constructed around 1276.[11]

Modern understanding of the historical record left behind by the Ancestral Puebloans exhibits a massive network of villages, storehouses, and fortified structures throughout the Colorado Plateau region. Stretching from Mesa Verde in the north, to Chaco Canyon in the east, to Keet Seel (Kitsʼiil) and Betatakin (Bitátʼahkin) and Wupatki in the west, trading routes can be traced through the Ganado region to as far south as Mexico. Pottery fragments found through the area show a wide array of design and utility, both local and foreign to Ganado. The largest population center in this era near Ganado, is 30 mi (50 km) to the north at Canyon de Chelly.

Between 1276 and 1299, archaeologists have recorded a period of "great drought," leading (among other causes) to the eventual end of influence of Puebloan culture and peoples on the Ganado region.

It is not known when the ancestors of the current Ganado community arrived in the Ganado region, though some suggest after 1400. The historical record left behind shows that the first Navajo people were of hunter-gatherer communities, who evolved into a nexus of agrarian society and pastoral society as the conditions of the area suited. Empowered by evolutionary dry farming techniques acquired via the neighboring Puebloan peoples, the early Ganado community's main crops consisted of beans, corn, and squash.

The early Ganado Navajo, like the modern people today, were speakers of a Na-Dené Southern Athabaskan languages known as Diné bizaad (lit. 'People's language'). Archaeological data suggests these peoples arrived in the present day Four Corners & Colorado Plateau regions in approximately the 15th century. The Navajo language retains cultural and linguistic aspects of this primary dialect and is somewhat mutually intelligible with the Western Apache language.[12]

When the Spanish Conquistadors arrived in the southwestern Arizona–New Mexico region, they encountered these peoples, and subsequently named them Apaches de Nabajó[13] Though distant relatives of the Apache peoples, these Apaches de Nabajó were different in both lineage and pathways to the area, from other Apache bands.

Jilhéél & Kin Naazinii (Upstanding House)

A mix of oral legend and archeology suggest that singer, and warrior/ runner Jilhéél came to the Ganado area in the early 18th century. It is believed that he traveled extensively and lived amongst the Puebloan people along the Rio Grande, and migrated with many of them to the refuge of Dinetah at the start of the Spanish invasion and occupation of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico.

In Jilhéél, it is also believed, came many of the cultural, architectural and agricultural influences to the greater Ganado region. Research suggests that Jilhéél contributed to the construction of fortifications to the north and south, notably in the hills east of Wide Ruins 15 miles to the southeast of Ganado. Archaeologist David M. Brugge offers that Jilhéél "might have been a local headman of the mid-1770s, possibly a refugee from Awatobi, considering his clan (Táchiiʼnii) and his move to Black Mesa, a refuge of Tobacco Táchiiʼnii people from Awatobi." Oral history research suggests that he inhabited "Wide Ruins, (meaning the Ancestral Puebloan site) and, a few miles north up Wide Ruins Wash, at" the citadel of "Kin Naazinii (Upstanding House)"; if not contributed to its construction – with the help of elder Daalgai – "a Navajo fortified 'pueblito' that archaeologists date at 1720–1805 (NLC, site S-MLC-UP-L; Bannister and others 1966:8; Navajo Nation 1967:263, 271, 285; Gilpin 1996)." Thus, Jilhéél is believed to have traveled between here "north to Canyon de Chelly" regularly.

Oral histories tells of a Jilhéél who carried "gigantic arrows, and had enormous feet. The sight of his footprints struck terror in his enemies. Some say he was a hunter who could run down deer; others say he knew various healing and war ceremonies. Some say he was of the Red Streak into Water (Táchiiʼnii) clan and later moved to Black Mesa." His fame amongst Navajo oral history is well known amongst various historical families. "Some of his attributes may reflect late pre-" Hispanic "iconography (big feet, for example, a common petroglyph motif). These pre-" Hispanic " associations of Jilhéél, together with the idea that Wide Ruins was some kind of 'boundary' place between Hopi and Zuni zones ..., makes one wonder if the north-south travel corridor through Wide Ruins to Canyon de Chelly could have been a late 'everyone's land' as conceptualized by LaBlanc (1999:70, 333) between settlement clusters" much older.[14]

"The north-south corridor that Jilhéél stalked encompasses a string of places with names that came from incidents of raiding and warfare before the Fort Sumner captivity. Several recorded Navajo oral histories tell the stories (HUTR oral history interviews 21, 36, 44, 142; Kelley and Francis 1993–2005, project KF9906, 5/21 and 6/17/99, and project KF9507, 8/14/98). The place names, from south to north, are Anaaʼ Hajiina (Where the Enemy Came Up) north of Chambers; Dzilgha Adahjééʼ (Where the White Mountain Apaches Ran Down or Hilltop Descent), near Ganado", and the modern day location of Ganado Mucho's burial site; "and Dzilgha Haaskai (White Mountain Apaches Went Up, or Hilltop Ascent) near Chinle, Arizona (see Map 1). The places near Ganado and Chinle are places where Apaches came from the south up the corridor and massacred Navajos. (See also Nequatewa 1967:52 and Stephen 1930:1018–1019 for Hopi accounts of a killing of Hopis by Navajos in 1858 west of Ganado; local Navajo accounts apparently of the same incident have been recorded [HUTR interviews 44 and 142], one of which describes the massacre as an Apache attack on Navajos, perhaps reflecting confusion between the name for White Mountain Apaches and the almost identical word for hilltop)."

New Spain

As a result of Ganado's location at the crossroads of ancient trade routes and pueblos, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado's exploration party passed near the Ganado area in 1540–1542 en route to the famous Hopi Villages 50 mi (80 km) to the west. "Spanish colonial and later sources beginning with the 1540 Spanish Entrada (a detachment of the Coronado expedition) record indigenous trails linking the Wide Ruins area to Zuni and Awatobi.[14]

As the silver mines funded greater and greater Spanish expansion into the frontier of "New Spain," King Philip II of Spain directed Conquistador Juan de Oñate to begin establishing Holy See missions in Nuevo México. As Roman Catholicism spread, by the 1629, "the mission of San Bernardino was established at Awátobi by a party of four Franciscans headed by Father Francisco de Porras",[15] as the Hopi villages were architecturally accommodating as built up population centers.

Spanish traffic was sustained from La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís to the outlying Hopi mission up until the 1680 Popé's Rebellion. In the "spring of AD 1700 Father Juan Garaycoecha visited the remains of the Hopi mission at the request of the inhabitants"; later that year, the remaining mission was soon after destroyed. The years 1778 to 1780 saw the first recorded drought to be experienced by the European and tribal historians alike, and was devastating to the regional population. The Spanish withdrawal from the region encompassing Ganado, continued until the American invasion of the 1800s.

Navajo and Hopi oral traditions tell how some people escaped and joined Navajos in the surrounding countryside near and far, giving rise to the Tobacco Táchiiʼnii clan (Clinton 1990, Brugge 1985, 1994; Courlander 1971).

Invasion and Ganado Mucho

The Ganado area remained relatively independent from rebellions of European ethnicity at Santa Fe until 1849. Ganado's first event under the American government came when a Hopi delegation was sent to Santa Fe in 1850. In 1858, Joseph Christmas Ives led an expedition through the area near Ganado. From 1821, the Navajo people had been engaged in the Navajo Wars against the Spanish, Mexican, and American invaders until the 1864 forced removal from their homelands. This exodus known as the Long Walk, would not see legal Navajo return until June 18, 1868.[16]

One Navajo elder said of the Long Walk:

By slow stages we traveled eastward by present Gallup and Chusbbito, Bear Spring, which is now called Fort Wingate. You ask how they treated us? If there was room the soldiers put the women and children on the wagons. Some even let them ride behind them on their horses. I have never been able to understand a people who killed you one day and on the next played with your children...?[17]

By 1869, the Ganado area had been fully occupied by the United States Government at Fort Defiance.[15]

During the Long Walk, Diné Chief totsohnii Hastiin (pronounced Toe-so-knee haaus-teen)(Navajo for Man of the big water Clan), famously known as Ganado Mucho (1809–1893), along with other leaders targeted by the United States (such as Manuelito) fled to the haven of the Grand Canyon. "Of both Hopi and Navajo ancestry, Ganado Mucho was a cautious man who was inclined toward diplomacy".[18] During the 1859 to 1861 period of resistance fighting, Ganado Mucho led the Ganado area on a policy of neutrality. This maneuver protected the Navajo residents of Ganado's wealth, held in their livestock, from United States confiscation by Kit Carson.

By 1866, Ganado Mucho surrendered and was remanded to the Bosque Redondo reservation near Fort Sumner, New Mexico. When he, Barboncito and Manuelito arrived, they found James Henry Carleton's experiment of resettlement a complete failure. While held in custody there, Ganado Mucho's son was murdered. He addressed directly the New Mexican Superintendent of Indian Affairs – A. Baldwin Norton – and condemned the conditions at Bosque Redondo.[18] After the treaty of 1868, Ganado Mucho and his community returned to Ganado. Following, Ganado Mucho was "appointed subchief of the western Navajo by General William Tecumseh Sherman. He lived there until his death, and is buried on a hillside between Ganado and Cornfields.[19]

Hubbell trading post

The first American settlements in the Ganado area were located near what is now Ganado Lake, and was established in 1871 as a trading post owned by Charles Crary. A second post operated by "Old Man" William B. Leonard opened soon after. These trading posts were established as a service to the Navajo people after the formation of the Fort Defiance Indian reservation, as a means to provide goods not locally available.

The first name for the settlement was probably Pueblo Colorado when Don Lorenzo Hubbell (1853–1930) moved into the area in 1876. Two years later, he purchased his world-famous homestead, trading post and out buildings from William Leonard, which were constructed in 1874. Legend says that in an effort not to confuse visitors in the area with Pueblo, Colorado, Hubbell changed the name of the settlement to Ganado in honor of Ganado Mucho, the twelfth signer of the Navajo peace treaty of 1868.[20]

Born to an Anglo father, and Spanish mother, Hubbell was raised at Pajarito Mesa, New Mexico. He was twenty three when he relocated to Ganado. He married Lina Rubi, and the couple had two sons (Roman and Lorenzo Jr.) and two daughters (Adele and Barbara). The family added onto the current adobe building which would become the famous Hubbell home, which hosted such guests as Theodore Roosevelt. The Hubbell garden contained Virginia creeper, a lawn, as well as native wild and yellow roses, lilac and yucca.

Hubbell died in 1930, and his youngest son, Roman Hubbell, assumed management duties. The stone Hogan (cottage) was constructed by Roman and his wife Dorothy in the early 1930s as a memorial to the elder Hubbell. Upon Roman's death in 1957, Dorothy maintained operations until 1967 when the National Park Service acquired the homestead. Hubbell, his wife, three of his children, a daughter-in-law, and a granddaughter are buried on the cone-shaped hill northwest of the trading post. Many Horses, son of Ganado Mucho, is also interred at this Hubbell family cemetery.

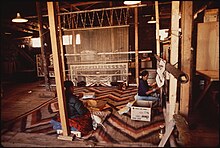

Hubbell contributed to encouraging the Ganado textiles market and local Navajo weaving houses.

Other retail trading posts included Ganado Trading, and Shillingburg's (later Round Top). The Presbyterian Church established a mission, school and hospital in Ganado in 1901.[20]

The hidden cost of the Navajo relocation by the United States government were felt in many ways. The most direct would be in the forced removal of their children to boarding schools from the late 19th century into the 20th century. Many Ganado area youth were sent to such government and Christian boardings schools such as at Fort Apache.[21] In most cases, the children were far removed from their families to foreign locations. Research has shown that such Americanization practices by the boarding schools, employed first by Captain Richard Henry Pratt served to destroy any last vestiges of Navajo identity, and Ganado children during this period were not immune to such inhumane practices.[22][23] Pratt's systemic Americanization of Native Americans by forced cultural assimilation, used as a model for Indian Boarding schools all over America, was later regarded by some as a form of cultural genocide.[24]

Modern Ganado

The Ganado community today is of the most advanced communities on the Navajo Nation. Agricultural parcels are managed by a local board of Farming advocates, and the surrounding ranches are sources of organic beef and mutton. The high school men and woman basketball teams are state renowned for their gamesmanship. Sage Memorial Hospital serves thousands of Hopi and Navajo patients, while affording ethnic Navajo experience to resident physicians and nurses. Hubbell Trading Post hosts a yearly art show in late summer which includes displays of art, jewelry, and rug weaving. The Ganado Rodeo Club also hosts events. The greater Ganado community is quite active, and throughout the winter months hold numerous Navajo religious ceremonies. Ganado municipal legislators also contribute largely to the policy and decision making of the Navajo Nation Government, most recently, in the tribal decision to reorganize the membership of the Navajo Nation Council.

Education

Ganado is served by the Ganado Unified School District. The district is served by Ganado Elementary School (North and South); Ganado Middle School; and Ganado High School, which host the region's athletic (football, track and field, swimming, basketball) facilities.

Ganado hosts satellite campuses for various collegiate level schools such as Diné College and Northern Arizona University.

College of Ganado

Ganado was once home to the nursing school (founded in 1927) that would soon become the College of Ganado. The collegiate campus was located on the campus of the Presbyterian Mission. Several buildings, such as Adobe West Dormitory, Cedar Lodge, Locust Cottage, Greenawalt House, and Poncel Hall remain; many of the former campus buildings are utilized by Sage Memorial Hospital. Founded in 1901, the mission community soon elected to build a nursing school for the Ganado community in 1911. Dr. Clarence Salsbury and his wife Cora organized "the first nursing school for Native Americans at the mission in Ganado. The school trained some 100[25] women from more than twenty tribes and several foreign countries. The institution was accredited by the State of Arizona and its graduates were highly regarded in their field". Dr. William Worrall Mayo, founder of the Mayo Clinic was a guest lecturer there.[26]

Ganado Art Community

Ganado is home to Navajo weaving style "Ganado Red". From the early 1900s demand for Ganado-produced fine rugs and blankets has grown steadily and has become world-famous since Lorenzo Hubbell began fostering the art and marketplace at his trading post.

Ganado is home to small community of silversmiths, who specialize in Navajo Jewelry.

Transportation

The Ganado Airport is a general aviation airport controlled by the Navajo Nation. The runway is GRS natural surface-ungraded earth runway measuring approximately 4,420 feet (1,350 m), south of the junction of Indian Route 27, and Arizona State Route 264. Plans by the Ganado Chapter envision future plans for ASP-Asphalt pavement surface. No control tower, parking tarmac, storage hangars, or other facilities exist at this time.

Notable people

- Brett Helquist, artist

- Cynthia Tse Kimberlin, ethnomusicologist

- Myron Lizer, 10th vice president of the Navajo Nation

- Shelly Lowe, academic administrator

- James S. Wall, Roman Catholic bishop

References

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Ganado, Arizona

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Ganado CDP, Arizona". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Ganado, Arizona Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Ganado, AZ". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "Data Center Results".

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "Nahanni National Park Reserve". Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "Navajo Indians - Research Paper by Sandydy3". Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Hopi Indians". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "The Long Walk of the Navajo | Peoples of Mesa Verde".

- ^ Very Slim Man, Navajo elder, quoted by Richard Van Valkenburgh, Desert Magazine, April 1946, p. 23.

- ^ "Monkey's Navajo Nation Adventure". www.theguys.org. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Byrd H. Granger (1960). Arizona Place Names. University of Arizona Press. p. 12. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ "Fort Apache History". www.wmat.nsn.us. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Brainwashing and Boarding School". Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ "Reservation Boarding Schools". www.twofrog.com. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Delta Democrat-Times from Greenville, Mississippi on October 27, 1949 · Page 14". Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SMH history". Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

External links

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles needing additional references from July 2016

- All articles needing additional references

- Use mdy dates from October 2019

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing Navajo-language text

- Commons category link is on Wikidata

- Articles with VIAF identifiers

- Articles with J9U identifiers

- Articles with LCCN identifiers

- Articles with NARA identifiers

- Census-designated places in Apache County, Arizona

- Census-designated places in Arizona

- Populated places on the Navajo Nation