GM1 gangliosidoses

| GM1 gangliosidoses | |

|---|---|

| Other names: GM1 gangliosidosis | |

| |

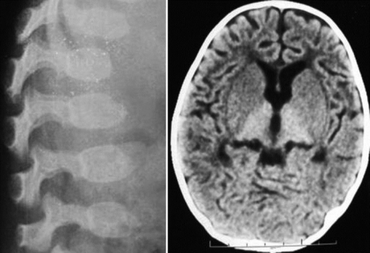

| GM1 gangliosidosis-X-ray indicates dysostosis multiplex at lumbar region and scan of brain indicates hyperdense thalamus | |

The GM1 gangliosidoses are caused by a deficiency of beta-galactosidase, with resulting abnormal storage of acidic lipid materials in cells of the central and peripheral nervous systems, but particularly in the nerve cells.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of this condition is as follows:[1]

- Neurodegeneration

- Seizures

- Spleen enlargement

- Coarsening of facial features

- Skeletal irregularities

- Joint stiffness

- Muscle weakness

Cause

GM1 Gangliosidoses are inherited, autosomal recessive sphingolipidoses, resulting from marked deficiency of Acid Beta Galactosidase.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Types

GM1 has three forms: early infantile, late infantile, and adult.[citation needed]

Early infantile GM1

Symptoms of early infantile GM1 (the most severe subtype, with onset shortly after birth) may include neurodegeneration, seizures, liver enlargement (hepatomegaly), spleen enlargement (splenomegaly), coarsening of facial features, skeletal irregularities, joint stiffness, distended abdomen, muscle weakness, exaggerated startle response to sound, and problems with gait.[citation needed]

About half of affected patients develop cherry-red spots in the eye.

Children may be deaf and blind by age 1 and often die by age 3 from cardiac complications or pneumonia.[2]

- Autosomal recessive disorder; beta-galactosidase deficiency; neuronal storage of GM1 ganglioside and visceral storage of galactosyl oligosaccharides and keratan sulfate.

- Early psychomotor deterioration: decreased activity and lethargy in the first weeks; never sit; feeding problems - failure to thrive; visual failure (nystagmus noted) by 6 months; initial hypotonia; later spasticity with pyramidal signs; secondary microcephaly develops; decerebrate rigidity by 1 year and death by age 1–2 years (due to pneumonia and respiratory failure); some have hyperacusis.

- Macular cherry-red spots in 50% by 6–10 months; corneal opacities in some

- Facial dysmorphology: frontal bossing, wide nasal bridge, facial edema (puffy eyelids); peripheral edema, epicanthus, long upper lip, microretrognathia, gingival hypertrophy (thick alveolar ridges), macroglossia

- Hepatomegaly by 6 months and splenomegaly later; some have cardiac failure

- Skeletal deformities: flexion contractures noted by 3 months; early subperiosteal bone formation (may be present at birth); diaphyseal widening later; demineralization; thoracolumbar vertebral hypoplasia and beaking at age 3–6 months; kyphoscoliosis. *Dysostosis multiplex (as in the mucopolysaccharidoses)

- 10–80% of peripheral lymphocytes are vacuolated; foamy histiocytes in bone marrow; visceral mucopolysaccharide storage similar to that in Hurler disease; GM1 storage in cerebral gray matter is 10-fold elevated (20–50-fold increased in viscera)

- Galactose-containing oligosacchariduria and moderate keratan sulfaturia

- Morquio disease Type B: Mutations with higher residual beta-galactosidase activity for the GM1 substrate than for keratan sulfate and other galactose-containing oligosaccharides have minimal neurologic involvement but severe dysostosis resembling Morquio disease type A (Mucopolysaccharidosis type 4).

Late infantile GM1

Onset of late infantile GM1 is typically between ages 1 and 3 years.Neurological symptoms include ataxia, seizures, dementia, and difficulties with speech.[citation needed]

Adult GM1

Onset of adult GM1 is between ages 3 and 30.

Symptoms include muscle atrophy, neurological complications that are less severe and progress at a slower rate than in other forms of the disorder, corneal clouding in some patients, and dystonia (sustained muscle contractions that cause twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal postures). Angiokeratomas may develop on the lower part of the trunk of the body. Most patients have a normal size liver and spleen.Prenatal diagnosis is possible by measurement of Acid Beta Galactosidase in cultured amniotic cells.[citation needed]

Treatment

This condition currently has no effective medical treatment, anticonvulsants may control seizures.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "GM1 gangliosidosis | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ Bley, Annette E.; Giannikopoulos, Ourania A.; Hayden, Doug; Kubilus, Kim; Tifft, Cynthia J.; Eichler, Florian S. (2011-11-01). "Natural History of Infantile GM2 Gangliosidosis". Pediatrics. 128 (5): e1233–e1241. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0078. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 3208966. PMID 22025593.

- ↑ Lyon, GL; et al. (1996), Neurology of Hereditary Metabolic Diseases of Children (2 ed.), pp. 53–55

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |