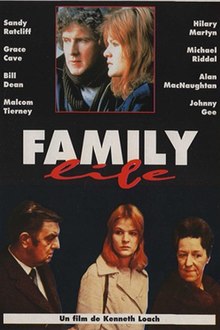

Family Life (1971 British film)

| Family Life | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Ken Loach |

| Screenplay by | David Mercer |

| Based on | TV play Two Minds by David Mercer |

| Produced by | Tony Garnett |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charles Stewart |

| Edited by | Roy Watts |

| Music by | Marc Wilkinson |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £180,000[1] |

| Box office | $1,827,374SEK ($291,648USD) |

Family Life (US: Wednesday's Child)[2] is a 1971 British drama film directed by Ken Loach from a screenplay by David Mercer.[3] It is a remake of In Two Minds, an episode of the BBC's Wednesday Play series first transmitted by the BBC in March 1967, which was also written by Mercer and directed by Loach.[4]

Plot

A young woman, Janice, is living with her conservative, working-class parents, who become concerned at her rebellious behaviour, and are shocked when she becomes pregnant. At a time when pregnancy when unmarried was widely considered shameful, they insist she has an abortion, but this has terrible emotional and mental effects on her. They constantly berate her for her behaviour, even when they visit her in hospital.

Cast

- Sandy Ratcliff as Janice Baildon

- Bill Dean as Mr. Baildon

- Grace Cave as Mrs. Baildon

- Malcolm Tierney as Tim

- Hilary Martyn as Barbara Baildon

- Michael Riddall as Dr. Donaldson

- Alan MacNaughtan as Mr. Caswell

- Johnny Gee as Man in the garden

Production

Development and Writing

Tony Garnett became interested in the work of psychiatrist R. D. Laing as a member of his family suffered from mental illness. He arranged for David Mercer to write a screenplay.[5] It resulted in the play Two Minds which Garnett said was inspired by the story of Julie, a case in Laing's 1960 book The Divided Self. "I regretted later it might be seen as scapegoating the mother," wrote Garnett.[6] Garnett wanted Roy Battersby to direct but he was unavailable so he went with Ken Loach.

The production was a success but Garnett said the fate and experience of his family member with the psychiatric profession "kept nagging away at me" so he decided to turn it into a film. Mercer was reluctant as "he rightly felt he had done the subject" but he was eventually persuaded. Garnett says Loach "didn't see the point but was easier to persuade. Directors always want to work in cinema."[7]

"It's the only subject where I've insisted we had two bites at the cherry, for my own personal reasons," said Garnett. "It was so important to me, to do with a woman in my life and a painful time. Although it wasn't necessarily a sensible thing to do, it was almost an obsession in me to try to understand what had gone on."[8]

Garnett claimed Mercer's "screenplay was barely adequate. It was lazy, perhaps because his heart wasn't in it. I wanted to do more work on it with him. He was reluctant. I probably should have called it a day then. With David on strike, but naturally reluctant to allow me to rewrite it, we had an insecure basis for a film. It was probably my fault for pressing him into it." However the producer says the movie was rescued by Loach who "gave a sense that we were witnessing life rather than actors doing their thing."[9]

Financing

Half the budget was provided by the National Film Finance Corporation, who had financed the script, the other half by Nat Cohen and Anglo-EMI.[10][11] Garnett wrote that when he pitched the project to Cohen, the producer summarised the story as "So, a mad girl goes into a mental hospital and goes madder. An unhappy ending. No laughs, no sex." He then said "You and Ken, you know, we could make a lot of money with you. If you weren't such a bunch of bloody communists."[12] Although Garnett and Loach wanted to use an unknown in the lead, Cohen gave the money.

Casting

Casting mixed professionals with amateurs. The mother was played by a suburban housewife and the psychiatrist by a real psychiatrist. Changes from the original included introducing a psychiatrist character and a boyfriend for the lead.[8]

Filming

There were clashes during filming as Mercer wanted his script filmed to the letter while Loach encouraged improvisation.[13]

Post-production

During editing, Loach was involved in a car accident that injured him and resulted in the death of his mother in law and five-year-old son.[14]

Release

The film was screened at the New York Film Festival on 3 October 1972.[15]

Box office

According to Loach the film made a "healthy profit".[10] However Garnett said it "did little business, as Nat had predicted, although long afterwards he had the grace to admit it was released and marketed badly. I don't think anyone knew how to sell it or even knew what it was really about." The film was very successful in France, however, where Laing's teachings were popular.[9] Loach's biographer says the film was a commercial failure and prevented him making a feature for several years.[16]

Critical reception

The Evening Standard called it "extraordinary".[17] Pauline Kael wrote "There are a few striking performances in the simulations of documentary footage. If you're not convinced by the Laing thesis, though, you may get very impatient."[18]

Variety called it "disturbing and provocative."[19]

Awards

Won

- 1972 Berlin International Film Festival:

- French Syndicate of Cinema Critics 1974:

- Critics Award – Best Foreign Film: Ken Loach (UK)

- Sydney Film Festival 2003:

- Audience Award – Best Feature-Length Fiction Film: Ken Loach

Nominated

- BAFTA Awards 1973:

- UN Award – Best Film

References

- ^ Walker, Alexander (1974). Hollywood, England. London & New York City: Harrap/Stein and Day. p. 381.

- ^ Roberts, Jerry (2009). Encyclopedia of Television Film Directors. Lanham, Maryland & Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. p. 344. ISBN 9780810863781.

- ^ "Family Life (1971)". BFI. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017.

- ^ Kemp, Philip (2003–14). "Family Life (1971)". BFI Screenonline. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Garnett p 167-169

- ^ Garnett p 171

- ^ Garnett p 173

- ^ a b Hayward p 122

- ^ a b Garnett p 175

- ^ a b Barnett, Anthony; McGrath, John; Mathews, John; Wollen, Peter (1976). "Interview with Tony Garnett and Ken Loach: Family Life in the making". Jump Cut (10–11): 43–45. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Harper, Sue; Smith, Justin T. (2012). British Film Culture: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 305. ISBN 9780748640782.

- ^ Garnett p 173-174

- ^ Hayward p 123

- ^ Hayward p 128-130

- ^ Greenspun, Roger (4 October 1972). "Film Fete: Woes of Womanas 'Wednesday's Child'". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Hayward p 127

- ^ "Unhappy families". Evening Standard. 13 January 1972. p. 21.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (1985). 5001 nights at the movies : a guide from A to Z. Henry Holt. p. 642. ISBN 9780805006193.

- ^ Variety Reviews 1971-74. 1983. p. 168.

Notes

- Garnett, Tony (2016). The day the music died : a memoir. Constable. ISBN 9781472122735.

- Hayward, Anthony (2004). Which side are you on? : Ken Loach and his films. Bloomsbury.

External links

- Family Life at IMDb

- Family Life at the BFI's Screenonline

- Review of film at Sight and Sound

- CS1: abbreviated year range

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from June 2016

- Use British English from June 2016

- 1971 films

- Template film date with 2 release dates

- 1971 drama films

- Films about sexual repression

- Films directed by Ken Loach

- Films scored by Marc Wilkinson

- British drama films

- EMI Films films

- Films about abortion

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s British films