Shigatoxigenic and verotoxigenic Escherichia coli

| Shigatoxigenic and verotoxigenic E. coli | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)[1] | |

| |

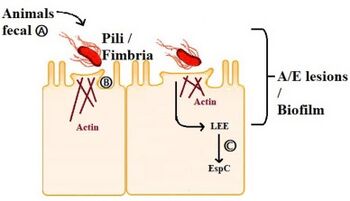

| Adherence mechanism of EHEC a) EHEC pathotypes from fecal ruminant reservoir colonize human intestinal epithelial cells b)EHEC strains to adhere to brush borders of epithelial cells through fimbrial/afimbrial adhesions c) EHEC produces EspC virulent proteins which causes A/E lesions [2] | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) and verotoxigenic E. coli (VTEC) are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli that produce Shiga toxin (or verotoxin).[lower-alpha 1] Only a minority of the strains cause illness in humans.[4][5]

The ones that do are collectively known as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) and are major causes of foodborne illness[1]. When infecting the large intestine of humans, they often cause gastroenteritis, enterocolitis, and bloody diarrhea (hence the name "enterohemorrhagic") and sometimes cause a severe complication called hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS).[6][7] Cattle are an important natural reservoir for EHEC because the colonised adult ruminants are asymptomatic. This is because they lack vascular expression of the target receptor for Shiga toxins.[8] The group and its subgroups are known by various names. They are distinguished from other strains of intestinal pathogenic E. coli including enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC).[9]

Bacteriology

Among the hemorrhagic E. coli, for example, we find that O157:H7 is gram-negative and oxidase-negative. Unlike many other strains, it does not ferment sorbitol, which provides a basis for clinical laboratory differentiation of the strain. [10][11]

Strains of E. coli that express Shiga and Shiga-like toxins gained that ability via infection with a prophage containing the structural gene coding for the toxin, and nonproducing strains may become infected and produce shiga-like toxins after incubation with shiga toxin positive strains. [10][11]

The prophage responsible seems to have infected the strain's ancestors fairly recently, as viral particles have been observed to replicate in the host if it is stressed in some way (e.g. antibiotics).[10][11]

Virulence

The infectivity or the virulence of an EHEC strain depends on several factors, including the presence of fucose in the medium, the sensing of this sugar and the activation of EHEC pathogenicity island.[1][5]

Regulation of the pathogenicity island

EHEC becomes pathogenic through the expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) encoded on its pathogenicity island. However, when EHEC is not in a host this expression is a waste of energy and resources, so it is only activated if some molecules are sensed in the environment. [12]

When QseC bind with one of their interacting signalling molecule, they autophosphorylate and transfer its phosphate to the response regulator. QseC senses adrenaline, noradrenaline, and an Endonuclease I-SceIII, encoded by a mobile group I intron within the mitochondrial COX1 gene ; whereas QseE senses adrenaline, noradrenaline, SO4 and PO4. These signals are a indication to bacteria that they are no longer free in the environment, but in the gut.As a result, QseC phosphorylates QseB, KpdE and QseF. QseE phosphorylates QseF. The products QseBC and QseEF repress the expression of FusK and FusR. FusK and FusR are the two components of a system to repress the transcription of the LEE genes. When fucose is present in the medium FusK phosphorylates FusR which represses LEE expression. Thus when EHEC enters the gut there is a competition between the signals coming from QseC and QseF, and the signal coming from FusK. The first two activate virulence, but Fusk stops it because the mucous layer, which is a source of fucose, isolates enterocytes from bacteria making the synthesis of the virulence factors useless. However, when fucose concentration decreases because bacterial cells find an unprotected area of the epithelium, then the expression of LEE genes will not be repressed by FusR, and KpdE will strongly activate them (in summary, the combined effect of the QseC/QseF and FusKR provide a fine-tuning system of LEE expression which saves energy and allow the mechanisms of virulence to be expressed only when the chances of success are higher).[13][14][12][15]

Shiga toxins

Shiga toxins are a major virulence factor of EHEC. The toxins interact with intestinal epithelium and can cause systematic complications in humans like HUS and cerebral dysfunction if they enter the circulation.[16] In EHEC, Shiga toxins are encoded lysogenic bacteriophages. The toxins bind to cell-surface glycolipid receptor Gb3, which causes the cell to take the toxin in via endocytosis. The Shiga toxins target ribosomal RNA, which inhibits protein synthesis and causes apoptosis.[17] The reason EHEC are symptomless in cattle is because the cattle do not have vascular expression of Gb3 unlike humans. Thus, the Shiga toxins cannot pass through the intestinal epithelium into circulation.[8]

FusKR complex

This complex, formed by two components (FusK and FusR) has the function in EHEC to detect the presence of fucose in the environment and regulate the activation of LEE genes as follows:

- FusK: is encoded by the z0462 gene. This gene is an histidine kinase sensor. It detects fucose and then phosphorylates the Z0463 gene activating it.[12][14]

- FusR: is encoded by the z0463 gene. This gene is a repressor of LEE genes, when z0462 gene detects fucose, phosphorylates and activates the Z0463 gene, which will repress the expression of 'ler', the regulator of the LEE genes. If z0463 gene is not active, the expression of the gene ler would not be repressed. The expression of 'ler' activates the remaining genes in the pathogenicity island inducing virulence.[14]

- At the same time, the system FusKR inhibits the Z0461 gene, a fucose transporter.[14]

Fucose increases the activation of the FusKR system, which inhibits the z0461 gene, which controls the metabolism of fucose. This is a mechanisms that is useful to avoid the competition for fucose with other strains of E. coli which are usually more efficient at using fucose as a carbon source. High concentrations of fucose in the medium also increases the repression of the LEE genes.With low levels of fucose in the environment, the FusKR system is inactive, and this means that z0461 gene is transcribed, thus increasing the metabolism of fucose. Furthermore, a low concentration of fucose is an indication of unprotected epithelium, thus the repression of ler genes will disappear and the expression of the LEE genes will allow to attack the adjacent cells.[14][12][18]

-

Inactivation of LEE genes ( ↑ [fucose] )

-

Activation of LEE genes ( ↓ [fucose] )

Infection

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation ranges from a mild and uncomplicated diarrhea to a hemorrhagic colitis with severe abdominal pain. Serotype O157:H7 may trigger an infectious dose with 100 bacterial cells or fewer; other strains such as 104:H4 has also caused an outbreak. Infections are most common in warmer months and in children under five years of age and are usually acquired from uncooked beef and unpasteurized milk and juice. Initially a non-bloody diarrhea develops in individuals after the bacterium attaches to the epithelium or the terminal ileum, cecum, and colon.[1][19][20][21]

Complications

In children, a complication can be hemolytic uremic syndrome which then uses cytotoxins to attack the cells in the gut, so that bacteria can leak out into the blood and cause endothelial injury in locations such as the kidney by binding to globotriaosylceramide [1]

EHECs that induce bloody diarrhea lead to HUS in 10% of cases. The clinical manifestations of postdiarrheal HUS include acute renal failure, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The verocytotoxin (shiga-like toxin) can directly damage renal and endothelial cells. Thrombocytopenia occurs as platelets are consumed by clotting. Hemolytic anemia results from intravascular fibrin deposition, increased fragility of red blood cells, and fragmentation.[9]

Diagnosis

A stool culture can detect the bacterium, although it is not a routine test and so must be specifically requested. The sample is cultured on sorbitol-MacConkey (SMAC) agar, or the variant cefixime potassium tellurite sorbitol-MacConkey agar (CT-SMAC)[22]

On SMAC agar, O157:H7 colonies appear clear due to their inability to ferment sorbitol, while the colonies of the usual sorbitol-fermenting serotypes of E. coli appear red. Sorbitol nonfermenting colonies are tested for the somatic O157 antigen before being confirmed as E. coli O157:H7.[23]

Like all cultures, diagnosis is time-consuming with this method; swifter diagnosis is possible using quick E. coli DNA extraction method plus PCR techniques.[23]

Treatment

Antibiotics are of questionable value and have not shown to be of clear clinical benefit. Antibiotics that interfere with DNA synthesis, such as fluoroquinolones, have been shown to induce the Stx-bearing bacteriophage and cause increased production of toxins.[24] Attempts to block toxin production with antibacterials which target the ribosomal protein synthesis are conceptually more attractive. Plasma exchange offers a controversial but possibly helpful treatment. The use of antimotility agents (medications that suppress diarrhea by slowing bowel transit) in children under 10 years of age or in elderly patients should be avoided, as they increase the risk of HUS with EHEC infections.[9]

Epidemiology

The best known of these strains is O157:H7, but non-O157 strains cause an estimated 36,000 illnesses, 1,000 hospitalizations and 30 deaths in the United States yearly.[25]

Food safety specialists recognize "Big Six" strains: O26; O45; O103; O111; O121; and O145.[25]

A 2011 outbreak in Germany was caused by another STEC, O104:H4. This strain has both enteroaggregative and enterohemorrhagic properties.[1][26][27]

Both the O145 and O104 strains can cause hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS)[28] both fairly in significant percentages.

Terminology

| Name[29] [30][31][32] | Short form |

|---|---|

| enterohemorrhagic E. coli | EHEC |

| hemolytic uremic syndrome–associated enterohemorrhagic E. coli | HUSEC |

| shiga toxin–producing E. coli | STEC |

| shigatoxigenic E. coli | STEC |

| shiga-like toxin–producing E. coli | SLTEC |

| verotoxin-producing E. coli | VTEC |

| verotoxigenic E. coli | VTEC |

| verocytotoxin-producing E. coli | VTEC |

| verocytotoxigenic E. coli | VTEC |

Names of the group and its subgroups include the following.[33] There is some polysemy involved. Invariable synonymity is indicated by having the same color. Beyond that there is also some wider but variable synonymity. The first two (purple) in their narrowest sense are generally treated as hypernyms of the others (red and blue), although in less precise usage the red and blue have often been treated as synonyms of the purple. At least one reference holds "EHEC" to be mutually exclusive of "VTEC" and "STEC",[6] but this does not match common usage, as many more publications lump all of the latter in with the former.

The current microbiology-based view on "Shiga-like toxin" (SLT) or "verotoxin" is that they should all be referred to as (versions of) Shiga toxin, as the difference is negligible. Following this view, all "VTEC" (blue) should be called "STEC" (red).[3][34]: 2–3

Historically, a different name was sometimes used because the toxins are not exactly the same as the one found in Shigella dysenteriae, down to every last amino acid residue, although by this logic every "STEC" would be a "VTEC". The line can also be drawn to use "STEC" for Stx1-producing strains and "VTEC" for Stx2-producing strains, since Stx1 is closer to the Shiga toxin. Practically, the choice of words and categories is not as important as the understanding of clinical relevance.[35][36]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Fatima, Rawish; Aziz, Muhammad (2024). "Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2022-10-23. Retrieved 2024-02-21.

- ↑ Govindarajan, Deenadayalan Karaiyagowder; Viswalingam, Nandhini; Meganathan, Yogesan; Kandaswamy, Kumaravel (1 September 2020). "Adherence patterns of Escherichia coli in the intestine and its role in pathogenesis". Medicine in Microecology. 5: 100025. doi:10.1016/j.medmic.2020.100025. ISSN 2590-0978. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Scheutz F, Teel LD, Beutin L, Piérard D, Buvens G, Karch H, Mellmann A, Caprioli A, Tozzoli R, Morabito S, Strockbine NA, Melton-Celsa AR, Sanchez M, Persson S, O'Brien AD (September 2012). "Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing Stx nomenclature". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 50 (9): 2951–63. doi:10.1128/JCM.00860-12. PMC 3421821. PMID 22760050.

- ↑ Croxen MA, Law RJ, Scholz R, Keeney KM, Wlodarska M, Finlay BB (2013). "Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (4): 822–80. doi:10.1128/CMR.00022-13. PMC 3811233. PMID 24092857.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Orth, D.; Wurzner, R. (1 November 2006). "What Makes an Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli?". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (9): 1168–1169. doi:10.1086/508207.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mainil, J (1999), "Shiga/verocytotoxins and Shiga/verotoxigenic Escherichia coli in animals", Vet Res, 30 (2–3): 235–57, PMID 10367357, archived from the original on 2018-09-26, retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ↑ Phillips, A; Navabpour, S; Hicks, S; Dougan, G; Wallis, T; Frankel, G (2000). "Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 target Peyer's patches in humans and cause attaching/effacing lesions in both human and bovine intestine". Gut. 47 (3): 377–381. doi:10.1136/gut.47.3.377. PMC 1728033. PMID 10940275.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pruimboom-Brees, I; Morgan, T; Ackermann, M; Nystrom, E; Samuel, J; Cornick, N; Moon, H (2000). "Cattle lack vascular receptors for Escherichia coli O157:H7 Shiga toxins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (19): 10325–10329. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710325P. doi:10.1073/pnas.190329997. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 27023. PMID 10973498.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Bae, Woo Kyun; Lee, Youn Kyoung; Cho, Min Seok; Ma, Seong Kwon; Kim, Soo Wan; Kim, Nam Ho; Choi, Ki Chul (2006-06-30). "A Case of Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Caused by Escherichia coli O104:H4". Yonsei Med J. 47 (3): 437–439. doi:10.3349/ymj.2006.47.3.437. PMC 2688167. PMID 16807997. Two sentences were taken from this source verbatim.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 O'Brien AD, Newland JW, Miller SF, Holmes RK, Smith HW, Formal SB (November 1984). "Shiga-like toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis or infantile diarrhea". Science. 226 (4675): 694–96. Bibcode:1984Sci...226..694O. doi:10.1126/science.6387911. PMID 6387911.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Strockbine NA, Marques LR, Newland JW, Smith HW, Holmes RK, O'Brien AD (July 1986). "Two toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain 933 encode antigenically distinct toxins with similar biologic activities". Infection and Immunity. 53 (1): 135–40. doi:10.1128/IAI.53.1.135-140.1986. PMC 260087. PMID 3522426.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Franzin, Fernanda M.; Sircili, Marcelo P. (2 February 2015). "Locus of Enterocyte Effacement: A Pathogenicity Island Involved in the Virulence of Enteropathogenic and Enterohemorragic Escherichia coli Subjected to a Complex Network of Gene Regulation". BioMed Research International. 2015: e534738. doi:10.1155/2015/534738. ISSN 2314-6133. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ↑ Hughes, David T.; Clarke, Marcie B.; Yamamoto, Kaneyoshi; Rasko, David A.; Sperandio, Vanessa (21 August 2009). "The QseC Adrenergic Signaling Cascade in Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)". PLOS Pathogens. 5 (8): e1000553. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000553. ISSN 1553-7374. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Pacheco, Alline R.; Curtis, Meredith M.; Ritchie, Jennifer M.; Munera, Diana; Waldor, Matthew K.; Moreira, Cristiano G.; Sperandio, Vanessa (December 2012). "Fucose sensing regulates bacterial intestinal colonization". Nature. 492 (7427): 113–117. doi:10.1038/nature11623. ISSN 1476-4687. Archived from the original on 2024-02-01. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ↑ Wu, Pan; Wang, Qian; Yang, Qian; Feng, Xiaohui; Liu, Xingmei; Sun, Hongmin; Yan, Jun; Kang, Chenbo; Liu, Bin; Liu, Yutao; Yang, Bin (January 2023). "A Novel Role of the Two-Component System Response Regulator UvrY in Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 Pathogenicity Regulation". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (3): 2297. doi:10.3390/ijms24032297. ISSN 1422-0067. Archived from the original on 2023-11-09. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ↑ Detzner, J; Pohlentz, G; Müthing, J (2020). "Valid Presumption of Shiga Toxin-Mediated Damage of Developing Erythrocytes in EHEC-Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome". Toxins. 12 (6): 373. doi:10.3390/toxins12060373. ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 7354503. PMID 32512916.

- ↑ Smith, D; Naylor, S; Gally, D (2002). "Consequences of EHEC colonisation in humans and cattle". International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 292 (3): 169–183. doi:10.1078/1438-4221-00202. ISSN 1438-4221. PMID 12398208.

- ↑ Segura, A; Bertoni, M; Auffret, P; Klopp, C; Bouchez, O; Genthon, C; Durand, A; Bertin, Y; Forano, E (23 October 2018). "Transcriptomic analysis reveals specific metabolic pathways of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in bovine digestive contents". BMC genomics. 19 (1): 766. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-5167-y. PMID 30352567.

- ↑ Ameer, Muhammad Atif; Wasey, Abdul; Salen, Philip (2024). "Escherichia coli (e Coli 0157 H7)". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2022-10-11. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ↑ "Infection by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Other Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) - Infectious Diseases". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 2024-02-05. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ↑ "BAM Chapter 4A: Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli". FDA. 2024. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ↑ "MACCONKEY SORBITOL AGAR (CT-SMAC)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Quick E. coli DNA extraction filter paper card". Archived from the original on 2014-07-17. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ↑ Zhang, X; McDaniel, AD; Wolf, LE; Keusch, GT; Waldor, MK; Acheson, DW (2000). "Quinolone antibiotics induce Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages, toxin production, and death in mice". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 181 (2): 664–70. doi:10.1086/315239. PMID 10669353.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Mallove, Zach (26 April 2010). "Lawyer Battles FSIS on Non-O157 E. coli". Food Safety News. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ Uphoff, H.; Hedrich, B.; Strotmann, I.; Arvand, M.; Bettge-Weller, G.; Hauri, A. M. (1 February 2014). "A prolonged investigation of an STEC-O104 cluster in Hesse, Germany, 2011 and implications for outbreak management". Journal of Public Health. 22 (1): 41–48. doi:10.1007/s10389-013-0595-2. ISSN 1613-2238. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ↑ Jandhyala, DM; Vanguri, V; Boll, EJ; Lai, Y; McCormick, BA; Leong, JM (September 2013). "Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4: an emerging pathogen with enhanced virulence". Infectious disease clinics of North America. 27 (3): 631–49. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2013.05.002. PMID 24011834. Archived from the original on 2023-01-21. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

- ↑ Ylinen, Elisa; Salmenlinna, Saara; Halkilahti, Jani; Jahnukainen, Timo; Korhonen, Linda; Virkkala, Tiia; Rimhanen-Finne, Ruska; Nuutinen, Matti; Kataja, Janne; Arikoski, Pekka; Linkosalo, Laura; Bai, Xiangning; Matussek, Andreas; Jalanko, Hannu; Saxén, Harri (1 September 2020). "Hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli in children: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcome". Pediatric Nephrology. 35 (9): 1749–1759. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04560-0. ISSN 1432-198X. Archived from the original on 25 December 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ↑ "Oxford Textbook of Zoonoses: Biology, Clinical Practice, and Public Health Control (2 edn) Get access Arrow". academic.oup.com. Archived from the original on 2023-01-01. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ↑ "E. Coli VTEC O157: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment". patient.info. 1 November 2023. Archived from the original on 4 November 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ↑ Etcheverría, AI; Padola, NL (1 July 2013). "Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: factors involved in virulence and cattle colonization". Virulence. 4 (5): 366–72. doi:10.4161/viru.24642. PMID 23624795. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ↑ Page, Andrea V.; Liles, W. Conrad (July 2013). "Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli Infections and the Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome". The Medical Clinics of North America. 97 (4): 681–695, xi. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2013.04.001. ISSN 1557-9859. Archived from the original on 2024-02-02. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

- ↑ Karch, Helge; Tarr, Phillip I.; Bielaszewska, Martina (2005). "Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli in human medicine". International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 295 (6–7): 405–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.06.009. PMID 16238016.

- ↑ Silva, Christopher J.; Brandon, David L.; Skinner, Craig B.; He, Xiaohua; et al. (2017), "Structure of Shiga Toxins and Other AB5 Toxins", Shiga toxins: A Review of Structure, Mechanism, and Detection, Springer, pp. 21–45, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50580-0_3, ISBN 978-3319505800, archived from the original on 2023-10-13, retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ↑ Chan, Yau Sang; Ng, Tzi Bun (1 February 2016). "Shiga toxins: from structure and mechanism to applications". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 100 (4): 1597–1610. doi:10.1007/s00253-015-7236-3. ISSN 1432-0614. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ↑ Melton-Celsa, Angela R. (15 August 2014). "Shiga Toxin (Stx) Classification, Structure, and Function". Microbiology Spectrum. 2 (4). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0024-2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

Further reading

- Bardiau, M.; M. Szalo & J.G. Mainil (2010). "Initial adherence of EPEC, EHEC and VTEC to host cells". Vet Res. 41 (5): 57. doi:10.1051/vetres/2010029. PMC 2881418. PMID 20423697.

- Wong, A.R.; et al. (2011). "Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: even more subversive elements". Mol Microbiol. 80 (6): 1420–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07661.x. PMID 21488979. S2CID 24606261.

- Tatsuno, I. (2007). "[Adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to human epithelial cells]". Nihon Saikingaku Zasshi. 62 (2): 247–53. doi:10.3412/jsb.62.247. PMID 17575791.

- Kaper, J.B.; J.P. Nataro & H.L. Mobley (2004). "Pathogenic Escherichia coli". Nat Rev Microbiol. 2 (2): 123–40. doi:10.1038/nrmicro818. PMID 15040260. S2CID 3343088.

- Garcia, A.; J.G. Fox & T.E. Besser (2010). "Zoonotic enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli: A One Health perspective". ILAR J. 51 (3): 221–32. doi:10.1093/ilar.51.3.221. PMID 21131723.

- Shimizu, T. (2010). "[Expression and extracellular release of Shiga toxin in enterohemorrahgic Escherichia coli]". Nihon Saikingaku Zasshi. 65 (2–4): 297–308. doi:10.3412/jsb.65.297. PMID 20505269.

| Classification |

|---|

![Inactivation of LEE genes ( ↑ [fucose] )](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e9/INACTIVATION_OF_LEE_GENES.jpg)

![Activation of LEE genes ( ↓ [fucose] )](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8b/ACTIVATION_OF_LEE_GENES.jpg)