Eculizumab

| Monoclonal antibody | |

|---|---|

| Type | Whole antibody |

| Source | Humanized (from mouse) |

| Target | Complement protein C5 |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Soliris, Elizaria, others |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intravenous infusion |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Elimination half-life | 8 to 15 days (mean 11 days) |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Molar mass | 148 kg/mol |

Eculizumab, sold under the brand name Soliris among others, is a medication used to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), and neuromyelitis optica. In people with PNH, it reduces both the destruction of red blood cells and need for blood transfusion, but does not appear to affect the risk of death.[1] Eculizumab was the first drug approved for each of its uses, and its approval was granted based on small trials.[2][3][4][5] It is given in a clinic by intravenous (IV) infusion.

Side effects include a risk for meningococcal infections and it is only prescribed to those who have enrolled in and follow a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy, which involves counseling people and ensuring that they are vaccinated.[6][7] It is a humanized monoclonal antibody functioning as a terminal complement inhibitor.[3]

It has been developed, manufactured, and marketed by Alexion Pharmaceuticals, which had patent exclusivity until 2017.[8]: 6

Medical uses

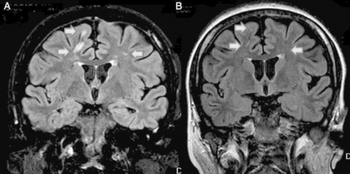

Eculizumab is used to treat atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).[6][7][5] For people with PNH, it improves quality of life and decreases the need for blood transfusions but does not appear to affect the risk of death.[1] It does not appear to change the risk of blood clots, myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myelogenous leukemia, or aplastic anemia.[1] Eculizumab is also used to treat neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in adults who are anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody positive.[2]

Eculizumab has also been explored as a treatment for CD55 deficiency, also known as CHAPLE syndrome, a rare genetic disorder of the immune system. With approval for compassionate off-label use, Kurolap and colleagues treated patients with the drug and found it to have positive clinical and laboratory outcomes over an 18-month period.[9]

Eculizumab is administered in a doctor's office or clinic by intravenous infusion.[7]

Women should not become pregnant while taking eculizumab and pregnant women should take it only if it is clearly necessary.[7]

Adverse effects

Eculizumab carries a black box warning for the risk of meningococcal infections and can only be prescribed by doctors who have enrolled in and follow a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy required by the FDA, which involves doctors counseling people to whom they are prescribing the drug, giving them educational materials, and ensuring that they are vaccinated, all of which must be documented.[6][7]

Eculizumab inhibits terminal complement activation and therefore makes people vulnerable to infection with encapsulated organisms. Life-threatening and fatal meningococcal infections have occurred in people who received eculizumab.[6] People receiving eculizumab have up to 2,000 times greater risk of developing invasive meningococcal disease.[10] Due to the increased risk of meningococcal infections, meningococcal vaccination is recommended at least 2 weeks prior to receiving eculizumab, unless the risks of delaying eculizumab therapy outweigh the risk of developing a meningococcal infection, in which case the meningococcal vaccine should be administered as soon as possible.[6] Both a serogroup A, C, W, Y conjugate meningococcal vaccine and a serogroup B meningococcal vaccine are recommended for people receiving eculizumab.[11] Receiving the recommended vaccinations may not prevent all meningococcal infections, especially from nongroupable N. meningiditis.[12] In 2017, it became clear that eculizumab has caused invasive meningococcal disease despite vaccination, because it interferes with the ability of antimeningococcal antibodies to protect against invasive disease.[13]

The drug's labels also carry warnings of severe anemia arising from the destruction of red blood cells as well as severe cases of blood clots forming in small blood vessels.[6][7]

Headaches are very common adverse effects, occurring in more than 10% of people who take the drug.[7]

Common adverse effects (occurring in between 1% and 10% of people who take the drug) include infections (pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infection, colds, and urinary tract infection), loss of white blood cells, loss of red blood cells, anaphylactic reaction, hypersensitivity reaction, loss of appetite, mood changes like depression and anxiety, a sense of tingling or numbness, blurred vision, vertigo, ringing in the ears, heart palpitations, high blood pressure, low blood pressure, vascular damage, peritonitis, constipation, upset stomach, swollen belly, itchy skin, increased sweating, blotches from small bleeds under the skin and skin redness, hives, muscle spasms, bone pain, back pain, neck pain, swollen joints, kidney damage, painful urination, spontaneous erections, general edema, chest pain, weakness, pain at the infusion site, and elevated transaminases.[7]

Pharmacology

Eculizumab specifically binds to the terminal complement component 5, or C5, which acts at a late stage in the complement cascade.[7] When activated, C5 is involved in activating host cells, thereby attracting pro-inflammatory immune cells, while also destroying cells by triggering pore formation. By inhibiting the complement cascade at this point, the normal, disease-preventing functions of proximal complement system are largely preserved, while the properties of C5 that promote inflammation and cell destruction are impeded.[15]

Eculizumab inhibits the cleavage of C5 by the C5 convertase into C5a a potent anaphylatoxin with prothrombotic and proinflammatory properties, and C5b, which then forms the terminal complement complex C5b-9 which also has prothrombotic and proinflammatory effects. Both C5a and C5b-9 cause the complement-mediated events that are characteristic of PNH and aHUS.[15]

The metabolism of eculizumab is thought to occur via lysosomal enzymes that cleave the antibody to generate small peptides and amino acids. The volume of distribution of eculizumab in humans approximates that of plasma.[4]

Chemistry

Eculizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against the complement protein C5.[3] It is an immunoglobulin G-kappa (IgGκ) consisting of human constant regions and murine complementarity-determining regions grafted onto human framework light and heavy chain variable regions. The compound contains two 448-amino acid heavy chains and two 214-amino acid light chains, and has a molecular weight of approximately 148 kilodaltons (kDa).[4]

Society and culture

Regulatory approval

Eculizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in March 2007 for the treatment of PNH,[4] Eculizumab has exclusivity rights until 2017, which protects it from competition until 2017.[8]: 6 When the FDA approved it in September 2011 for the treatment of aHUS, it designated it as an orphan drug.[16]

The 2011 FDA approval was based on two small prospective trials of 17 people and 20 people.[5][6][17]

The European Medicines Agency approved it for the treatment of PNH in June 2007,[7] and in November 2011 for the treatment of aHUS.[18] Health Canada approved it in 2009 to treat PNH and in 2013 as the only drug to treat aHUS.[19]

Eculizumab was approved by the FDA for AQP4+ NMO in 2019, based on the results of the PREVENT trial.[2]

Economics

As of 2014 there was insufficient evidence to show that eculizumab therapy improves life expectancy for people with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and the cost-effectiveness was poor.[20]

In 2010 Alexion priced Soliris as the most expensive drug in the world,[21] at approximately US$409,500 a year in the United States (2010),[21] €430,000 per year for ongoing treatment in the UK,[22][23] and $500,000 a year in Canada (2014).[24] Alexion started selling Soliris in 2008, making $295 million in 2007 with its stock price rising to 130% in 2010.[24]

In December 2013, New Zealand's government pharmaceutical buyer Pharmac declined a proposal to subsidize the drug after Alexion refused to budge on a NZ$670,000 (US$590,000) per person per year price and Pharmac's economic analysis determined the price would need to be halved before the drug was cost-effective enough to subsidize.[25] Pharmac's decision upset many people with PNH in New Zealand PNH,[26] although Pharmac has not ruled out reviewing the decision at a later date, should the drug be made available at a lower price.[25]

According to a 2014 report, the orphan drug market has become increasingly lucrative for a number of reasons. The cost of clinical trials for orphan drugs is substantially lower than for other diseases —trial sizes are naturally much smaller than for more common diseases that affect more people. Small clinical trials and little competition place these orphan agents at an advantage when they come up for regulatory review.[27] Further reduction to the cost of development is because of the tax incentives in the Orphan Drug Act of 1983. On average the cost per person for orphan drugs is "six times that of non-orphan drugs, a clear indication of their pricing power".[27] Although there are much smaller orphan disease populations, the cost of per-person outlays are the largest and are expected to increase with wider use of public subsidies.[27]

In December 2014, the provincial government of Ontario, Canada negotiated the price with the manufacturer, the only drug approved by Health Canada to treat aHUS. People can apply for it on "compassionate grounds" "on a case-by-case basis for example individuals who have been urgently hospitalized due to an immediate life-, limb-, or organ-threatening complication." It then was already "funded by the Ontario government for the treatment of another rare illness, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), through a bulk-buy deal reached by the provincial premiers in 2011."[24]

In February 2015, Canada's drug-price regulator took the rare step of calling a hearing into Soliris, accusing Alexion of exceeding the permissible price cap under the ""Highest International Price Comparison"" (HIPC).[28] In June 2015, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) under the Canadian Patent Act, held a preliminary hearing in Ottawa, Ontario to examine allegations. John Haslam, President and General Manager of Vaughan, Ontario-based Alexion Canada, was named as one of the respondents.[29] Alexion charges Canada $700,000 per person per year, more than anywhere else in the world.[30] Alexion denies the claim. In Canada "provincial drug plans have already negotiated secret discounts on Soliris for many of the patients they cover."[28]

As of 2015, while Eculizumab in PNH was associated with 1.13 additional life years and 2.45 quality of life years QALYs, there has been a high incremental cost (CAN$5.24 million) and a substantial opportunity cost. A 2014 Canadian study calculated the cost per life-year-gained with treatment as CAN$4.62 million (US$4,571,564) and cost per quality-adjusted-life-year as CAN$2.13 million (US$2,112,398)."The incremental cost per life year and per QALY gained is CAN$4.62 million and CAN$2.13 million, respectively. Based on established thresholds, the opportunity cost of funding eculizumab is 102.3 discounted QALYs per patient funded."[31]

By 2015, industry analysts and academic researchers agreed that the high price of orphan drugs, such as eculizumab, was not related to research, development, and manufacturing costs: their price is arbitrary and they have become more profitable than traditional medicines.[30] Sachdev Sidhu, a University of Toronto scientist, who spent ten years at Genentech before academia, estimated that public science was responsible for well over 80% of the work. "Public resources went into understanding the molecular basis of the disease, public resources went into the technology to make antibodies and finally, Alexion, to their credit, kind of picked up the pieces." The cost of manufacturing Soliris' monoclonal antibodies is less than "1 percent of the price of the drug," he said.[30]

Brazil's supreme court had decided in April 2018 to break the patent of Soliris in Brazil following local law. This medicine was only provided by the government's health system (SUS) and now it can be produced by other companies in that country.[32]

Biosimilar competition

While the FDA will not approve biosimilar applications for Eculizumab before 16 March 2019,[8]: 6 there is an ongoing debate over the length of exclusivity periods. National regulators protect orphan drug producers from competition with biosimilar products through a multi-year exclusivity period, it is challenged as markets open and international trade deals are negotiated —such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).[8] A generic version, branded "Elizaria'", is available in Russia.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Martí-Carvajal, AJ; Anand, V; Cardona, AF; Solà, I (30 October 2014). "Eculizumab for treating patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD010340. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010340.pub2. PMID 25356860.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Commissioner, Office of the (27 June 2019). "FDA approves first treatment for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, a rare autoimmune disease of the central nervous system". FDA. FDA. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Russell P Rother, Scott A Rollins, Christopher F Mojcik et al. (2007). "Discovery and development of the complement inhibitor eculizumab for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria". Nat Biotechnol. 25 (11): 1256–1264. doi:10.1038/nbt1344. PMID 17989688. S2CID 22732675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Andrew Dmytrijuk, Kathy Robie-Suh, Martin H. Cohen, Dwaine Rieves, Karen Weiss, Richard Pazdur (2008). "FDA report eculizumab (Soliris) for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria". The Oncologist. 13 (9): 993–1000. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0086. PMID 18784156.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Keating, GM (December 2013). "Eculizumab: a review of its use in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome". Drugs. 73 (18): 2053–66. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0147-7. PMID 24249647. S2CID 36682579.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 "Eculizumab label" (PDF). FDA. January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021. For label updates, see FDA index page for BLA 125166 Archived 16 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 "Soliris - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 23 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Andrew Fischer Bourgoin, Beth Nuskey (April 2015). An Outlook on Biosimilar Competition (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Kurolap, Alina; Eshach Adiv, Orly; Hershkovitz, Tova; Tabib, Adi; Karbian, Netanel; Paperna, Tamar; Mory, Adi; Vachyan, Arcadi; Slijper, Nadav; Steinberg, Ran; Zohar, Yaniv (March 2019). "Eculizumab Is Safe and Effective as a Long-term Treatment for Protein-losing Enteropathy Due to CD55 Deficiency". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 68 (3): 325–333. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000002198. ISSN 0277-2116. PMID 30418410. S2CID 53281594. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ "HAN Archive - 00404|Health Alert Network (HAN)". emergency.cdc.gov. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Folaranmi, T; et al. (12 June 2015). "Use of Serogroup B Meningococcal Vaccines in Persons Aged ≥10 Years at Increased Risk for Serogroup B Meningococcal Disease: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 64 (22): 608–612. PMC 4584923. PMID 26068564. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ McNamara, Lucy A; Topaz, Nadav; Wang, Xin; et al. (7 July 2017). "High Risk for Invasive Meningococcal Disease Among Patients Receiving Eculizumab (Soliris) Despite Receipt of Meningococcal Vaccine". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66 (Early Release): 734–737. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6627e1. PMC 5687588. PMID 28704351.

- ↑ McNamara, Lucy A.; Topaz, Nadav; Wang, Xin; Hariri, Susan; Fox, Leanne; MacNeil, Jessica R. (2017). "High Risk for Invasive Meningococcal Disease Among Patients Receiving Eculizumab (Soliris) Despite Receipt of Meningococcal Vaccine". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66 (27): 734–737. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6627e1. PMC 5687588. PMID 28704351.

- ↑ Xiao, Hai; Wu, Ka; Liang, Xiaoliu; Li, Rong; Lai, Keng Po (2021). "Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Eculizumab for Treating Myasthenia Gravis". Frontiers in Immunology. 12. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.715036/full. ISSN 1664-3224.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Brodsky, RA; Hoffman R, Benz EJ Jr, Shattil S; et al. (2009). "Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria". Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice: 385–395.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "FDA approves Soliris for rare pediatric blood disorder: Orphan drug receives second approval for rare disease", FDA, 23 September 2011, archived from the original on 18 January 2017, retrieved 25 June 2015

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (30 April 1990). "Orphan Drug Law Spurs Debate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ↑ "EU/3/09/653". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "In The Matter Of The Patent Act, R.S.C., 1985, C. P-4, As Amended" (PDF). Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2015.

- ↑ Coyle D, Cheung MC, Evans GA (July 2014). "Opportunity Cost of Funding Drugs for Rare Diseases: The Cost-Effectiveness of Eculizumab in Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria". Med Decis Making. 34 (8): 1016–29. doi:10.1177/0272989X14539731. PMID 24990825. S2CID 206498664.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Herper, Matthew (19 February 2010), "The World's Most Expensive Drugs", Forbes, archived from the original on 28 April 2021, retrieved 25 June 2015

- ↑ Martin Wall Doctors must tell patients of errors, under new Varadkar law. Like a motoring ‘hit and run’ for doctors to fail to make such disclosures, says Minister Archived 30 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine Feb 5, 2015, Irish Times

- ↑ High cost of treatment for rare blood disorder needs to be clarified, says NICE in draft guidance Archived 25 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine 04 March 2014, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. UK

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Gallant, Jacques (4 December 2014), Toronto woman with rare disease fights province for life-saving but costly drug, The Toronto Star, archived from the original on 14 August 2020, retrieved 24 September 2021

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Citing unreasonable price, PHARMAC declines eculizumab funding proposal". Pharmaceutical Management Agency. 11 December 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- ↑ "Plea to Pharmac for pricey life-saver". 3 News NZ. 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Hadjivasiliou, Andreas (October 2014), "Orphan Drug Report 2014" (PDF), EvaluatePharma, archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2015, retrieved 28 June 2015 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "EvaluatePharma_2014" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 28.0 28.1 Blackwell, Tom (3 February 2015), "World's most expensive drug — which costs up to $700,000 per year — too expensive, Canada says", National Post, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 25 June 2015

- ↑ "Motions and Exhibits" (PDF), Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, 2015, archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2020, retrieved 25 June 2015

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Crowe, Kelly (25 June 2015), "How pharmaceutical company Alexion set the price of the world's most expensive drug: Cost of one of world's most expensive drugs shrouded in corporate secrecy", CBC News, archived from the original on 26 June 2015, retrieved 25 June 2015

- ↑ Doug Coyle, Matthew C. Cheung, Gerald A. Evans (November 2014). "Opportunity Cost of Funding Drugs for Rare Diseases: The Cost-Effectiveness of Eculizumab in Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria". Medical Decision Making. 34 (8): 1016–1029. doi:10.1177/0272989X14539731. PMID 24990825. S2CID 206498664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Reuters (19 April 2018), STJ atende a pedido da AGU e quebra patente do medicamento Soliris, archived from the original on 16 June 2018

- ↑ "Elizaria®". www.generium.ru. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- "Eculizumab". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Pages with reference errors

- CS1 maint: uses authors parameter

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Use dmy dates from December 2013

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Infobox-drug molecular-weight unexpected-character

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Drugs that are a monoclonal antibody

- Chemicals that do not have a ChemSpider ID assigned

- Articles with changed EBI identifier

- Orphan drugs

- Immunosuppressants