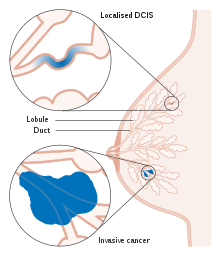

Ductal carcinoma in situ

| Breast cancer in situ | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Intraductal carcinoma, ductal intraepithelial neoplasia[1] | |

| |

| Ducts of the mammary gland, the location of ductal carcinoma | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | None, nipple discharge, rash at the nipple, breast lump[1] |

| Types | Comedo, cribriform, micropapillary, papillary, solid[2] |

| Risk factors | Older age, family history, not having children, genetics[2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Mammogram, biopsy[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Invasive breast cancer[3] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Good[5] |

| Frequency | >60,000 women/yr (USA)[5] |

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), also known as intraductal carcinoma, is a pre-cancerous or non-invasive cancer of the breast.[6][7] It rarely produces symptoms; typically being detected by screening mammography, though occasionally nipple discharge, rash at the nipple, or a breast lump may occur.[1][2] About 20% of cases develop into invasive breast cancer; though, this may be as high as 60% without treatment during prolonged follow-up.[8][9]

Risk factors include older age, family history, not having children, and the genetic changes BRCA1 and BRCA2.[2][3] The abnormal cells only occur within breast ducts; though this may involve a large area of the breast.[10] Diagnosis is generally suspected when a mammogram finds calcification; with tissue biopsy used for confirmation.[4][2] It is classified as stage 0 cancer and can vary from low-grade to high-grade.[1]

Treatment is generally by surgery, either a lumpectomy or a mastectomy.[1] Other treatments that may be used include radiation therapy and hormone therapy.[1] With treatment life expectancy is typically normal; though, over 20 years the risk of death from breast cancer is three times greater at about 3%.[3]

DCIS is diagnosed in more than 60,000 women in the United States and 7,000 in the United Kingdom per year.[5][1] It represents about 25% of breast cancer in women and about 10% of male breast cancer.[5][11] Rates have increased from less than 5% before screening programs launched.[3] There is disagreement on its status as cancer; with some bodies include DCIS when calculating breast cancer statistics, while others do not.[12]

Terminology

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) literally means groups of "cancerous" epithelial cells which remained in their normal location (in situ) within the ducts and lobules of the mammary gland.[13] Clinically, it is considered a premalignant (i.e. potentially malignant) condition,[14] because the biologically abnormal cells have not yet crossed the basement membrane to invade the surrounding tissue.[13][15] When multiple lesions (known as "foci" of DCIS) are present in different quadrants of the breast, this is referred to as "multicentric" disease.[16]

Some count DCIS as a "cancer", whereas others do not.[17][18] When classified as a cancer, it is referred to as a non-invasive or pre-invasive form.[13][19] The National Cancer Institute describes it as a "noninvasive condition".[17]

Signs and symptoms

Most women who develop DCIS do not experience any symptoms. The majority of cases (80-85%) are detected through screening mammography. The first symptoms may appear if the cancer advances.

In a few cases, DCIS may cause:

- A lump or thickening in or near the breast or under the arm

- A change in the size or shape of the breast

- Nipple discharge or nipple tenderness; the nipple may also be inverted, or pulled back into the breast

- Ridges or pitting of the breast; the skin may look like the skin of an orange

- A change in the way the skin of the breast, areola, or nipple looks or feels[20] such as warmth, swelling, redness or scaliness.[21]

Causes

The specific causes of DCIS are still unknown. The risk factors for developing this condition are similar to those for invasive breast cancer.[22]

Some women are however more prone than others to developing DCIS. Women considered at higher risks are those who have a family history of breast cancer, those who have had their periods at an early age or who have had a late menopause. Also, women who have never had children or had them late in life are also more likely to get this condition.

Long-term use of estrogen-progestin hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for more than five years after menopause, genetic mutations (BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes), atypical hyperplasia, as well as radiation exposure or exposure to certain chemicals may also contribute in the development of the condition.[23] Nonetheless, the risk of developing noninvasive cancer increases with age and it is higher in women older than 45 years.

Diagnosis

80% of cases in the United States are detected by mammography screening.[24] More definitive diagnosis is made by breast biopsy for histopathology.

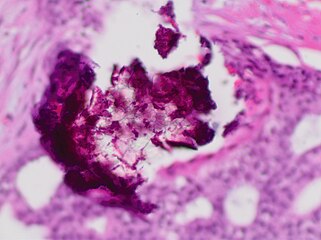

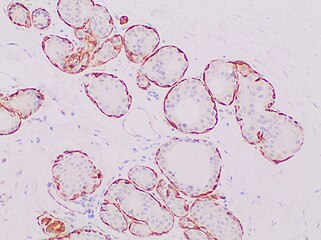

It is classified according to the architectural pattern of the cells (solid, cribriform, papillary, and micropapillary), tumor grade (high, intermediate, and low grade), the presence or absence of comedo histology,[16] or the cell type forming the lesion in the case of the apocrine cell-based in situ carcinoma, apocrine ductal carcinoma in situ.[25]

-

Mammogram microcalcifications in ductal carcinoma in situ

-

Histopathology of dystrophic microcalcifications in DCIS, H&E stain.

-

Histopathologic architectural patterns of DCIS.[26]

-

Histopathology of high-grade DCIS. H&E stain.

RBC = red blood cell.[27] -

DCIS with microinvasion, defined as focus of invasive cancer measuring up to 1.0 mm in size.[28]

-

Immunohistochemistry for calponin in ductal carcinoma in situ, highlighting myoepithelial cells around all tumor cells, thereby ruling out invasive ductal carcinoma.

-

Ductal carcinoma in situ with comedo necrosis spanning 30% of its diameter, which is generally regarded as the minimal size to classify it as comedo.[29]

-

Histopathologic image from ductal cell carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of breast. Hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Treatment

There are different opinions on the best treatment.[30] Surgical removal, with or without additional radiation therapy or tamoxifen, is the recommended by the National Cancer Institute.[31] Surgery may be either a breast-conserving lumpectomy or a mastectomy (complete or partial removal of the affected breast).[32] A lumpectomy is often combined with radiation therapy.[17] Tamoxifen may be used as hormonal therapy if the cells show estrogen receptor positivity.[17] Survival is the same with lumpectomy as it is with mastectomy, whether or not a woman has radiation after lumpectomy.[33] Chemotherapy is not needed since the disease is noninvasive.[34]

While surgery reduces the risk of subsequent cancer, many people never develop cancer even without treatment and the associated side effects.[32] There is no evidence comparing surgery with watchful waiting and some feel watchful waiting may be a reasonable option in certain cases.[32]

Mastectomy

There is no evidence that mastectomy decreases the risk of death over a lumpectomy.[35] Mastectomy, however, may decrease the rate of the DCIS or invasive cancer occurring in the same location.[36] [35]

Mastectomies remain a common recommendation in those with persistent microscopic involvement of margins after local excision or with a diagnosis of DCIS and evidence of suspicious, diffuse microcalcifications.[37]

Radiation

Radiation therapy after lumpectomy provides equivalent survival rates to mastectomy, although there is a slightly higher risk of recurrent disease in the same breast in the form of further DCIS or invasive breast cancer. Systematic reviews (including a Cochrane review) indicate that the addition of radiation therapy to lumpectomy reduces recurrence of DCIS or later onset of invasive breast cancer in comparison with breast-conserving surgery alone, without affecting mortality.[38][39][40] The Cochrane review did not find any evidence that the radiation therapy had any long-term toxic effects.[38] While the authors caution that longer follow-up will be required before a definitive conclusion can be reached regarding long-term toxicity, they point out that ongoing technical improvements should further restrict radiation exposure in healthy tissues.[38] They do recommend that comprehensive information on potential side effects is given to women who receive this treatment.[38] The addition of radiation therapy to lumpectomy appears to reduce the risk of local recurrence to approximately 12%, of which approximately half will be DCIS and half will be invasive breast cancer; the risk of recurrence is 1% for women undergoing mastectomy.[41]

Sentinel node biopsy

Some institutions that have encountered high rates of recurrent invasive cancers after mastectomy for DCIS have endorsed routine sentinel node biopsy (SNB).[42] However, research indicates that sentinel node biopsy has risks that outweigh the benefits for most women with DCIS.[43] SNB should be considered with tissue diagnosis of high-risk DCIS (grade III with palpable mass or larger size on imaging) as well as in people undergoing mastectomy after a core or excisional biopsy diagnosis of DCIS.[44][45]

Prognosis

With treatment, the prognosis is excellent, with greater than 97% long-term survival. If untreated, DCIS progresses to invasive cancer in roughly one-third of cases, usually in the same breast and quadrant as the earlier DCIS.[46] About 2% of women who are diagnosed with this condition and treated died within 10 years.[47] Biomarkers can identify which women who were initially diagnosed with DCIS are at high or low risk of subsequent invasive cancer.[48][49]

Epidemiology

DCIS is often detected with mammographies but can rarely be felt. With the increasing use of screening mammography, noninvasive cancers are more frequently diagnosed and now constitute 15% to 20% of all breast cancers.[37]

Cases have increased five-fold between 1983 and 2003 in the United States due to the introduction of screening mammography.[47] In 2009 about 62,000 cases were diagnosed.[47]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Radswiki, The. "Ductal carcinoma in situ | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Tomlinson-Hansen, S; Khan, M; Cassaro, S (January 2023). "Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ". StatPearls. PMID 33620843. Archived from the original on 2023-12-22. Retrieved 2024-01-17.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Breast cancer in situ - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment | BMJ Best Practice US". bestpractice.bmj.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 van Seijen, M; Lips, EH; Thompson, AM; Nik-Zainal, S; Futreal, A; Hwang, ES; Verschuur, E; Lane, J; Jonkers, J; Rea, DW; Wesseling, J; PRECISION, team (August 2019). "Ductal carcinoma in situ: to treat or not to treat, that is the question". British journal of cancer. 121 (4): 285–292. doi:10.1038/s41416-019-0478-6. PMID 31285590.

- ↑ Sinn, HP; Kreipe, H (May 2013). "A Brief Overview of the WHO Classification of Breast Tumors, 4th Edition, Focusing on Issues and Updates from the 3rd Edition". Breast Care. 8 (2): 149–154. doi:10.1159/000350774. PMC 3683948. PMID 24415964.

- ↑ Hindle, William H. (1999). Breast care: a clinical guidebook for women's primary health care providers. New York: Springer. p. 129. ISBN 9780387983486.

- ↑ Jones, Calley (12 October 2022). "Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: The Weight of the Word "Cancer"". American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ Hoffman, Abigail W.; Ibarra-Drendall, Catherine; Espina, Virginia; Liotta, Lance; Seewaldt, Victoria (June 2012). "Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: Challenges, Opportunities, and Uncharted Waters". American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book (32): 40–44. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.228.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer - Gynecology and Obstetrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ Nofal MN, Yousef AJ (December 2019). "The diagnosis of male breast cancer". The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 77 (10): 356–359. PMID 31880271. Archived from the original on 2023-01-29. Retrieved 2024-01-17.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer Screening (PDQ®) - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 15 December 2023. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Allred DC (2010). "Ductal carcinoma in situ: terminology, classification, and natural history". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2010 (41): 134–8. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq035. PMC 5161057. PMID 20956817.

- ↑ Padwal, David Hui (2011). Alexander Leung and Raj Padwal (ed.). Approach to internal medicine a resource book for clinical practice (3rd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 198. ISBN 9781441965059.

- ↑ Tjandra, Joe J.; Collins, John P. (2006). "Breast surgery". In Tjandra; et al. (eds.). Textbook of surgery (3rd ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. p. 282. ISBN 9780470757796.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Virnig BA, Shamliyan T, Tuttle TM, Kane RL, Wilt TJ (September 2009). "Diagnosis and management of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. AHRQ Publication No.09-E018. (185): 1–549. PMC 4781639. PMID 20629475. Archived from the original on 2014-01-31. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 "Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. January 1980. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Chang, Alfred (2007). Oncology: An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer. p. 162. ISBN 9780387310565. Archived from the original on 2024-01-16. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ↑ Saclarides, Theodore J.; Jonathan A. Myers; Keith W. Millikan, eds. (2008). Common surgical diseases an algorithmic approach to problem solving (2nd revised ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 9780387752464. Archived from the original on 2024-01-16. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer". Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Signs and Symptoms". Archived from the original on 2010-09-26. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "After the mammogram". Archived from the original on 2010-04-07. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Intraductal Carcinoma of the Breast". Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Ductal Carcinoma In Situ". cancer.gov. January 9, 2015. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Quinn CM, D'Arcy C, Wells C (January 2022). "Apocrine lesions of the breast". Virchows Archiv. 480 (1): 177–189. doi:10.1007/s00428-021-03185-4. PMC 8983539. PMID 34537861.

- ↑ Top and bottom left images by Mikael Häggström, MD. Bottom right image from:

Kulka, J.; Madaras, L.; Floris, G.; Lax, S.F. (2022). "Papillary lesions of the breast". Virchows Arch. 480 (1): 65–84. doi:10.1007/s00428-021-03182-7. PMC 8983543. PMID 34734332.

- "This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License" - ↑ Image by Mikael Häggström, MD. References for features:

- "Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast". Stanford Medical School. 2020-08-27. Archived from the original on 2023-03-30. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- Hayward, M.K.; Louise Jones, J.; Hall, A.; King, L.; Ironside, A.J.; Nelson, A.C.; et al. (2020). "Derivation of a nuclear heterogeneity image index to grade DCIS". Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 18: 4063–4070. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2020.11.040. PMC 7744935. PMID 33363702. - ↑ Image annotation by Mikael Häggström, MD, using source image from:

Moatasim A, Mamoon N (2022). "Primary Breast Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma and Review of Literature". Cureus. 14 (3): e23098. doi:10.7759/cureus.23098. PMC 8997314. PMID 35464581.

- "This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0."

Source for microinvasion: "Protocol for the Examination of Resection Specimens from Patients with Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) of the Breast, Version: 4.4.0.0. Protocol Posting Date: June 2021" (PDF). College of American Pathologists. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-01-01. Retrieved 2024-01-06. - ↑ Image by Mikael Häggström, MD.

- Reference for 30% being the most common definition of comedo necrosis by size:

- Harrison, B.T.; Hwang, E.S.; Partridge, A.H.; Thompson, A.M.; Schnitt, S.J. (2019). "Variability in diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis among breast pathologists: implications for patient eligibility for active surveillance trials of ductal carcinoma in situ". Mod Pathol. 32 (9): 1257–1262. doi:10.1038/s41379-019-0262-4. PMID 30980039. Archived from the original on 2024-01-16. Retrieved 2024-01-06. - ↑ Mannu, Gurdeep S.; Bettencourt-Silva, Joao H.; Ahmed, Farid; Cunnick, Giles (2015). "A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey of UK Breast Surgeons' Views on the Management of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ". International Journal of Breast Cancer. 2015: 104231. doi:10.1155/2015/104231. PMC 4677188. PMID 26697227.

- ↑ "Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: Treatment Options for Patients With DCIS". National Cancer Institute at NIH. National Institutes of Health. 2014-07-11. Archived from the original on 2015-04-09. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ: an uncertain harm-benefit balance". Prescrire Int. 22 (144): 298–303. Dec 2013. PMID 24600734.

- ↑ J, Cuzick; I, Sestak; Se, Pinder; Io, Ellis; S, Forsyth; Nj, Bundred; Jf, Forbes; H, Bishop; Is, Fentiman (January 2011). "Effect of Tamoxifen and Radiotherapy in Women With Locally Excised Ductal Carcinoma in Situ: Long-Term Results From the UK/ANZ DCIS Trial". The Lancet. Oncology. 12 (1): 21–9. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70266-7. PMC 3018565. PMID 21145284.

- ↑ Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS) Archived 2015-04-24 at the Wayback Machine, Johns Hopkins Medicine

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Virnig, BA; Shamliyan, T; Tuttle, TM; Kane, RL; Wilt, TJ (September 2009). "Diagnosis and management of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (185): 4. PMC 4781639. PMID 20629475.

They found women undergoing mastectomy were less likely than women undergoing lumpectomy plus radiation to experience local DCIS or invasive recurrence. Women undergoing BCS alone were also more likely to experience a local recurrence than women treated with mastectomy. We found no study showing a mortality reduction associated with mastectomy over breast conserving surgery with or without radiation

- ↑ Mannu, GS; Wang, Z; Broggio, J; Charman, J; Cheung, S; Kearins, O; Dodwell, D; Darby, SC (27 May 2020). "Invasive breast cancer and breast cancer mortality after ductal carcinoma in situ in women attending for breast screening in England, 1988-2014: population based observational cohort study". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 369: m1570. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1570. PMC 7251423. PMID 32461218.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Intraductal carcinoma". Archived from the original on 2016-04-10. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Goodwin A, Parker S, Ghersi D, Wilcken N (2013). "Post-operative radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD000563. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000563.pub7. PMID 24259251.

- ↑ Virnig, BA; Tuttle, TM; Shamliyan, T; Kane, RL (2010). "Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment, and outcomes". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 102 (3): 170–8. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp482. PMID 20071685.

- ↑ Correa, C.; McGale, P.; Taylor, C.; Wang, Y.; Clarke, M.; Davies, C.; Peto, R.; Bijker, N.; Solin, L.; Darby, S.; Darby, S (2010). "Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2010 (41): 162–177. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq039. ISSN 1745-6614. PMC 5161078. PMID 20956824.

- ↑ "NIH DCIS Consensus Conference Statement". National Institutes of Health. September 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-08-13. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ↑ Tan JC, McCready DR, Easson AM, Leong WL (February 2007). "Role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in ductal carcinoma-in-situ treated by mastectomy". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 14 (2): 638–45. doi:10.1245/s10434-006-9211-9. PMID 17103256. S2CID 1924867.

- ↑ Hung, Peiyin; Wang, Shi-Yi; Killelea, Brigid K.; Mougalian, Sarah S.; Evans, Suzanne B.; Sedghi, Tannaz; Gross, Cary P. (2019-12-01). "Long-Term Outcomes of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ". JNCI Cancer Spectrum. 3 (4): pkz052. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkz052. PMC 7049982. PMID 32337481.

- ↑ Mannu, GS; Groen, EJ; Wang, Z; Schaapveld, M; Lips, EH; Chung, M; Joore, I; van Leeuwen, FE; Teertstra, HJ; Winter-Warnars, GAO; Darby, SC; Wesseling, J (November 2019). "Reliability of preoperative breast biopsies showing ductal carcinoma in situ and implications for non-operative treatment: a cohort study". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 178 (2): 409–418. doi:10.1007/s10549-019-05362-1. PMC 6797705. PMID 31388937.

- ↑ van Deurzen CH, Hobbelink MG, van Hillegersberg R, van Diest PJ (April 2007). "Is there an indication for sentinel node biopsy in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast? A review". European Journal of Cancer. 43 (6): 993–1001. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.010. PMID 17300928.

- ↑ Basic Pathology, Robbins (2018). Breast. Copyright © 2018 by Elsevier Inc. p. 743. ISBN 978-0-323-35317-5.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Kerlikowske, K (2010). "Epidemiology of ductal carcinoma in situ". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2010 (41): 139–41. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq027. PMC 5161058. PMID 20956818.

- ↑ Kerlikowske, K.; Molinaro, A. M.; Gauthier, M. L.; Berman, H. K.; Waldman, F.; Bennington, J.; Sanchez, H.; Jimenez, C.; Stewart, K.; et al. (2010). "Biomarker Expression and Risk of Subsequent Tumors After Initial Ductal Carcinoma in Situ Diagnosis". JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 102 (9): 627–637. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq101. PMC 2864293. PMID 20427430.

- ↑ Witkiewicz AK, Dasgupta A, Nguyen KH, et al. (June 2009). "Stromal caveolin-1 levels predict early DCIS progression to invasive breast cancer". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 8 (11): 1071–1079. doi:10.4161/cbt.8.11.8874. PMID 19502809. Archived from the original on 2020-03-27. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

![Histopathologic architectural patterns of DCIS.[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Histopathologic_architectural_patterns_of_DCIS.png/288px-Histopathologic_architectural_patterns_of_DCIS.png)

![Histopathology of high-grade DCIS. H&E stain. RBC = red blood cell.[27]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/Histopathology_of_high-grade_DCIS.png/202px-Histopathology_of_high-grade_DCIS.png)

![DCIS with microinvasion, defined as focus of invasive cancer measuring up to 1.0 mm in size.[28]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Histopathology_of_microinvasive_ductal_carcinoma_in_situ.png/289px-Histopathology_of_microinvasive_ductal_carcinoma_in_situ.png)

![Ductal carcinoma in situ with comedo necrosis spanning 30% of its diameter, which is generally regarded as the minimal size to classify it as comedo.[29]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/Histopathology_of_ductal_carcinoma_in_situ_with_comedo_necrosis.jpg/321px-Histopathology_of_ductal_carcinoma_in_situ_with_comedo_necrosis.jpg)