Drunk driving

Drunk driving (or drink-driving in British English[1]) is the act of driving under the influence of alcohol. A small increase in the blood alcohol content increases the relative risk of a motor vehicle crash.[2]

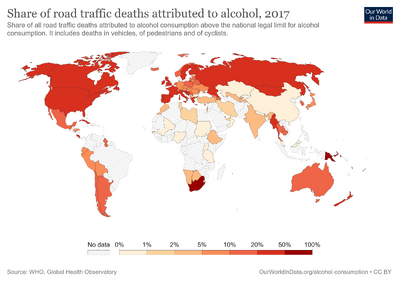

In the United States, alcohol is involved in 30% of all traffic fatalities.[3]

Effects of alcohol on cognitive processes

Alcohol has a very significant effect on the functions of the body which are vital to driving and being able to function. Alcohol is a depressant, which mainly affects the function of the brain. Alcohol first affects the most vital components of the brain and "when the brain cortex is released from its functions of integrating and control, processes related to judgment and behavior occur in a disorganized fashion and the proper operation of behavioral tasks becomes disrupted."[4] Alcohol weakens a variety of skills that are necessary to perform everyday tasks.

One of the main effects of alcohol is severely impairing a person's ability to shift attention from one thing to another, "without significantly impairing sensory motor functions."[4] This indicates that people who are intoxicated are not able to properly shift their attention without affecting the senses. People that are intoxicated also have a much more narrow area of usable vision than people who are sober. The information the brain receives from the eyes "becomes disrupted if eyes must be turned to the side to detect stimuli, or if eyes must be moved quickly from one point to another."[4]

Several testing mechanisms are used to gauge a person's ability to drive, which indicate levels of intoxication. One of these is referred to as a tracking task, testing hand–eye coordination, in which "the task is to keep an object on a prescribed path by controlling its position through turning a steering wheel. Impairment of performance is seen at BACs of as little as 0.7 mg/mL (0.066%)."[4] Another form of tests is a choice reaction task, which deals more primarily with cognitive function. In this form of testing both hearing and vision are tested and drivers must give a "response according to rules that necessitate mental processing before giving the answer."[4] This is a useful gauge because in an actual driving situation drivers must divide their attention "between a tracking task and surveillance of the environment."[4] It has been found that even "very low BACs are sufficient to produce significant impairment of performance" in this area of thought process.[4]

Grand Rapids Dip

Studies suggest that a BAC of 0.01–0.04% would slightly lower the risk, referred to as the Grand Rapids Effect or Grand Rapids Dip,[5][6] based on a seminal research study by Borkenstein, et al.[7] (Robert Frank Borkenstein is well known for inventing the Drunkometer in 1938, and the breathalyzer in 1954.)[8]

Some literature has attributed the Grand Rapids Effect to erroneous data or asserted (without support) that it was possibly due to drivers exerting extra caution at low BAC levels or to "experience" in drinking. Other explanations are that this effect is at least in part the blocking effect of ethanol excitotoxicity and the effect of alcohol in essential tremor and other movement disorders,[9] but this remains speculative.

Perceived recovery rate

A direct effect of alcohol on a person's brain is an overestimation of how quickly their body is recovering from the effects of alcohol. A study, discussed in the article "Why drunk drivers may get behind the wheel", was done with college students in which the students were tested with "a hidden maze learning task as their BAC [Blood Alcohol Content] both rose and fell over an 8-hour period."[2] The researchers found through the study that as the students became more drunk there was an increase in their mistakes "and the recovery of the underlying cognitive impairments that lead to these errors is slower, and more closely tied to the actual blood alcohol concentration, than the more rapid reduction in participants' subjective feeling of drunkenness."[2]

The participants believed that they were recovering from the adverse effects of alcohol much more quickly than they actually were. This feeling of perceived recovery is a plausible explanation of why so many people feel that they are able to safely operate a motor vehicle when they are not yet fully recovered from the alcohol they have consumed, indicating that the recovery rates do not coincide.

This thought process and brain function that is lost under the influence of alcohol is a very key element in regards to being able to drive safely, including "making judgments in terms of traveling through intersections or changing lanes when driving."[2] These essential driving skills are lost while a person is under the influence of alcohol.

Characteristics of drunk drivers

Personality traits

Although situations differ and each person is unique, some common traits have been identified among drunk drivers. In the study "personality traits and mental health of severe drunk drivers in Sweden", 162 Swedish DUI offenders of all ages were studied to find links in psychological factors and characteristics. There are a wide variety of characteristics common among DUI offenders which are discussed, including: "anxiety, depression, inhibition, low assertiveness, neuroticism and introversion".[10] There is also a more specific personality type found, typically more antisocial, among repeat DUI offenders. It is not uncommon for them to actually be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and exhibit some of the following personality traits: "low social responsiveness, lack of self-control, hostility, poor decision-making lifestyle, low emotional adjustment, aggression, sensation seeking and impulsivity".[10]

It is also common for offenders to use drinking as a coping mechanism, not necessarily for social or enjoyment reasons, when they are antisocial in nature and have a father with a history of alcoholism. Offenders who begin drinking at an earlier age for thrills and "fun" are more likely to be antisocial later in their lives. The majority of the sample, 72%, came from what is considered more "normal" circumstances. This group was older when they began drinking, came from families without a history of alcoholism, were relatively well-behaved as children, were not as physically and emotionally affected by alcohol when compared with the rest of the study, and had the less emotional complications, such as anxiety and depression. The smaller portion of the sample, 28%, comes from what is generally considered less than desirable circumstances, or "not normal". They tended to start drinking heavily earlier in life and "exhibited more premorbid risk factors, had a more severe substance abuse and psychosocial impairment."[10]

Various characteristics associated with drunk drivers were found more often in one gender than another. Females were more likely to be affected by both mental and physical health problems, have family and social problems, have a greater drug use, and were frequently unemployed. However, the females tended to have less legal issues than the typical male offender. Some specific issues females dealt with were that "almost half of the female alcoholics had previously attempted to commit suicide, and almost one-third had suffered from anxiety disorder." In contrast with females, males were more likely to have in-depth problems and more involved complications, such as "a more complex problem profile, i.e. more legal, psychological, and work-related problems when compared with female alcoholics."[10] In general the sample, when paralleled with control groups, was tested to be much more impulsive in general.

Another commonality among the whole group was that the DUI offenders were more underprivileged when compared with the general population of drivers. A correlation has been found between lack of conscientiousness and accidents, meaning that "low conscientiousness drivers were more often involved in driving accidents than other drivers." When tested the drivers scored very high in the areas of "depression, vulnerability (to stress), gregariousness, modesty, tender mindedness", but significantly lower in the areas of "ideas (intellectual curiosity), competence, achievement striving and self-discipline."[10] The sample also tested considerably higher than the norm in "somatization, obsessions–compulsions, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoia, psychoticism", especially in the area of depression. Through this testing a previously overlooked character trait of DUI offenders was uncovered by the "low scores on the openness to experience domain."[10] This area "includes intellectual curiosity, receptivity to the inner world of fantasy and imagination, appreciation of art and beauty, openness to inner emotions, values, and active experiences." In all these various factors, there is only one which indicates relapses for driving under the influence: depression.[10]

Cognitive processes

Not only can personality traits of DUI offenders be dissimilar from the rest of the population, but so can their thought processes, or cognitive processes. They are unique in that "they often drink despite the severity of legal and financial sanctions imposed on them by society."[11]

In addition to these societal restraints, DUI offenders ignore their own personal experience, including both social and physical consequences. The study "Cognitive Predictors of Alcohol Involvement and Alcohol consumption-Related Consequences in a Sample of Drunk-Driving Offenders" was performed in Albuquerque, New Mexico on the cognitive, or mental, factors of DUI offenders. Characteristics such as gender, marital status, and age of these DWI offenders were similar to those in other populations. Approximately 25% of female and 21% of male offenders had received "a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse" and 62% of females and 70% of males "received a diagnosis of alcohol dependence."[11] All of the offenders had at least one DWI and males were more likely to have multiple citations. In terms of drinking patterns approximately 25% stated that "they had drunk alcohol with in the past day, while an additional 32% indicated they had drunk within the past week."[11] In regards to domestic drinking, "25% of the sample drank at least once per week in their own homes."[11] Different items were tested to see if they played a role in the decision to drink alcohol, which includes socializing, the expectation that drinking is enjoyable, financial resources to purchase alcohol, and liberation from stress at the work place. The study also focused on two main areas, "intrapersonal cues", or internal cues, that are reactions "to internal psychological or physical events" and "interpersonal cues" that result from "social influences in drinking situations."[11] The two largest factors between tested areas were damaging alcohol use and its correlation to "drinking urges/triggers."[11] Once again different behaviors are characteristic of male and female. Males are "more likely to abuse alcohol, be arrested for DWI offenses, and report more adverse alcohol-related consequences." However, effects of alcohol on females vary because the female metabolism processes alcohol significantly when compared to males, which increases their chances for intoxication.[11] The largest indicator for drinking was situational cues which comprised "indicators tapping psychological (e.g. letting oneself down, having an argument with a friend, and getting angry at something), social (e.g. relaxing and having a good time), and somatic cues (e.g. how good it tasted, passing by a liquor store, and heightened sexual enjoyment)."[11]

It may be that internal forces are more likely to drive DWI offenders to drink than external, which is indicated by the fact that the brain and body play a greater role than social influences. This possibility seems particularly likely in repeat DWI offenders, as repeat offences (unlike first-time offences) are not positively correlated with the availability of alcohol.[12] Another cognitive factor may be that of using alcohol to cope with problems. It is becoming increasingly apparent that the DWI offenders do not use proper coping mechanisms and thus turn to alcohol for the answer. Examples of such issues "include fights, arguments, and problems with people at work, all of which imply a need for adaptive coping strategies to help the high-risk drinker to offset pressures or demands."[11] DWI offenders would typically prefer to turn to alcohol than more healthy coping mechanisms and alcohol can cause more anger which can result in a vicious circle of drinking more alcohol to deal with alcohol-related issues. This is a not the way professionals tell people how to best deal with the struggles of everyday life and calls for "the need to develop internal control and self-regulatory mechanisms that attenuate stress, mollify the influence of relapse-based cues, and dampen urges to drink as part of therapeutic interventions."[11]

Implied consent laws

There are laws in place to protect citizens from drunk drivers, called implied consent laws. Drivers of any motor vehicle automatically consent to these laws, which include the associated testing, when they begin driving.

In most jurisdictions (with the notable exception of a few, such as Brazil), refusing consent is a different crime than a DWI itself and has its own set of consequences. There have been cases where drivers were "acquitted of the DWI offense and convicted of the refusal (they are separate offenses), often with significant consequences (usually license suspension)".[13] A driver must give their full consent to comply with testing because "anything short of an unqualified, unequivocal assent to take the Breathalyzer test constitutes a refusal."[13] It has also been ruled that defendants are not allowed to request testing after they have already refused in order to aid officers' jobs "to remove intoxicated drivers from the roadways" and ensure that all results are accurate.[13]

United States

Implied consent laws are found in all 50 U.S. states and require drivers to submit to chemical testing, called evidentiary blood alcohol tests, after arrest. These laws have thus far been shown to be in compliance with the Constitution and are legal. Implied consent laws typically result in civil law consequences (but applying criminal penalties), such as a driver's license suspension.

In order to invoke implied consent, the police must establish probable cause. Field Sobriety Tests (FSTs or SFSTs), Preliminary Breath Tests (PBTs) are often used to obtain such probable cause evidence, necessary for arrest or invoking implied consent.[13]

Some states have passed laws that impose criminal penalties based upon principles of implied consent.[14] However, in 2016, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that Kansans who refuse to submit to either a breath or blood test in DUI investigations cannot be criminally prosecuted for that refusal. The court found unconstitutional a state law making it a crime to refuse such a test when no court-ordered warrant exists. In its 6-1 ruling, the court found that the tests were in essence searches and the law punishes people for exercising their constitutional right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.[15]

Birchfield v. North Dakota

Subsequently, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Birchfield v. North Dakota, held that a breath test, but not a blood test, may be administered as a search incident to a lawful arrest for drunk driving. The Court stated, "Because breath tests are significantly less intrusive than blood tests and in most cases amply serve law enforcement interests, a breath test, but not a blood test, may be administered as a search incident to a lawful arrest for drunk driving." The Court held that no warrant is needed for an evidentiary breath testing, but that a warrant is required for criminal prosecution for a blood test refusal. Birchfield leaves open the possibility of pseudo-criminal "civil" penalties for blood test refusals (under implied consent, without a warrant); however most law enforcement agencies are responding to Birchfield by requesting evidential breath tests, due to the criminal status of evidential breath test refusals.

Non-evidential testing

In the US, implied consent laws generally do not apply to Preliminary Breath Test (PBT) testing (small handheld devices, as opposed to evidential breath test devices). For a handheld field breath tester to be used as evidential breath testing, the device must be properly certified and calibrated, evidential procedures must be followed, and it may be necessary to administer an "implied consent" warning to the suspect prior to testing.[citation needed]

For some violations, such as refusals by commercial drivers or by drivers under 21 years of age, some US jurisdictions may impose implied consent consequences for a PBT refusal.[citation needed] For example, the state of Michigan has a roadside PBT law[16] that requires motorist a preliminary breath test;[17] however, for non-commercial drivers Michigan's penalties are limited to a "civil infraction" penalty, with no violation "points",[18] [19] but is not considered to be a refusal under the general implied consent law.[20]

Participation in "field sobriety tests" (FSTs or SFSTs) is voluntary in the US.[21][22]

Solutions

Reducing alcohol consumption

Studies have shown that there are various methods to help reduce alcohol consumption:

- increasing the price of alcohol.[23]

- restricting opening hours of places where alcohol can be bought and consumed

- restricting places where alcohol can be bought and consumed, such as banning the sale of alcohol in petrol stations and transport cafes

- increasing the minimum drinking age.[23]

Separating drinking from driving

One tool used to separate drinking from driving is an ignition interlock device which requires the driver to blow into a mouthpiece on the device before starting or continuing to operate the vehicle.[23] This tool is used in rehabilitation programmes and for school buses.[23] Studies have indicated that ignition interlock devices can reduce drunk driving offences by between 35% and 90%, including 60% for a Swedish study, 67% for the CDCP, and 64% for the mean of several studies.[23] The US may require monitoring systems to stop intoxicated drivers in new vehicles as early as 2026.[24]

Designated driver programmes

A designated driver programme helps to separate driving from drinking in social places such as restaurants, discos, pubs, bars. In such a programme, a group chooses who will be the drivers before going to a place where alcohol will be consumed; the drivers abstain from alcohol. Members of the group who do not drive would be expected to pay for a taxi when it is their turn.[23]

Reducing the legal blood alcohol concentration limit

Reduction of legal limit from 0.8 g/L to 0.5 g/L reduced fatal crashes by 2% in some European countries; while similar results were obtained in the United States[23] Lower legal limit (0.1 g/L in Austria and 0 g/L in Australia and the United States) have helped to reduce fatalities among young drivers. However, in Scotland, lowering the legal limit of blood alcohol content from 0.08% to 0.05% did not result in fewer road traffic accidents in two years after the introducing the new law. One possible explanation is that this might be due the poor publicity and enforcement of the new law and the lack of random breath testing.[25][26]

Police enforcement

Enforcing the legal limit for alcohol consumption is the usual method to reduce drunk driving.

Experience shows that:

- introduction of breath testing devices by the police in the 1970s had a significant effect, but alcohol remains a factor in 25% of all fatal crashes in Europe[23]

- fines appear to have little effect on reducing alcohol-impaired driving[23]

- driving licence measures with a duration of 3 to 12 months[clarification needed]

- imprisonment is the least effective remedy

Education

Education programmes used to reduce drunk driving levels include:

- driver education in schools and in basic driver training

- driver improvement courses on alcohol (rehabilitation courses)

- public campaigns

- promotion of safety culture

Prevalence in Europe

About 25% of all road fatalities in Europe are alcohol-related, while very few Europeans drive under the influence of alcohol.

According to estimates, 3.85% of drivers in European Union drive with a BAC of 0.2 g/L and 1.65% with a BAC of 0.5 g/L and higher. For alcohol in combination with drugs and medicines, the rates are respectively 0.35% and 0.16%.[23]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "drink-driving". Collins Dictionary. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Why drunk drivers may get behind the wheel". Science Daily. 18 August 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "Alcohol-Impaired Driving". NHTSA. 2018. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Mattila, Maurice J. (2001). Encyclopedia of drugs, alcohol and addictive behavior. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 0028655419.

- ↑ Grand Rapids Effects Revisited: Accidents, Alcohol and Risk Archived 7 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, H.-P. Krüger, J. Kazenwadel and M. Vollrath, Center for Traffic Sciences, University of Wuerzburg, Röntgenring 11, D-97070 Würzburg, Germany

- ↑ "NTSB (US) report on Grand Rapids Effect". Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ Robert F. Borkenstein papers, 1928-2002 Archived 26 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Indiana U. The role of the drinking driver in traffic accidents Archived 13 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine (Researchgate link)

- ↑ Center for Studies of Law in Action, Robert F. Borkenstein Courses Archived 1 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Indiana U.

- ↑ Mostile G, Jankovic J (October 2010). "Alcohol in essential tremor and other movement disorders". Movement Disorders. 25 (14): 2274–84. doi:10.1002/mds.23240. PMID 20721919. S2CID 39981956.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Huckba, B. (July 2010). "Personality traits and mental health of severe drunk drivers in Sweden". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 45 (7): 723–31. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0111-8. PMID 19730762. S2CID 20165169.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 Scheier, L. M.; Lapham, S. C.; C’de Baca, J. (2008). "Cognitive predictors of alcohol involvement and alcohol-related consequences in a sample of drunk-driving offenders". Substance Use & Misuse. 43 (14): 2089–2115. doi:10.1080/10826080802345358. PMID 19085438. S2CID 25196512. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Schofield, Timothy B.; Denson, Thomas F. (7 August 2013). "Temporal Alcohol Availability Predicts First-Time Drunk Driving, but Not Repeat Offending". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e71169. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...871169S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071169. PMC 3737138. PMID 23940711.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Ogundipe, K. A.; Weiss, K. J. (2009). "Drunk driving, implied consent, and self-incrimination". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 37 (3): 386–91. PMID 19767505.

- ↑ Soronen, Lisa (12 January 2016). "Blood Alcohol Testing: No Consent, No Warrant, No Crime?". NCSL. National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ Rizzo, Tony (26 February 2016). "Kansas DUI law that makes test refusal a crime is ruled unconstitutional". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "Michigan Vehicle Code § 257.625a". Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "Michigan State Police **Breath Test Program and Training Information**". Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "SOS - Substance Abuse and Driving". Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "DUI - DUI court case". Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ Committee, Oregon Legislative Counsel. "ORS 813.136 (2015) - Consequence of refusal or failure to submit to field sobriety tests". Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ DUI: Refusal to Take a Field Test, or Blood, Breath or Urine Test Archived 6 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, NOLO Press ("As a general rule (and unlike chemical testing), there is no legal penalty for refusing to take these tests although the arresting officer can typically testify as to your refusal in court.")

- ↑ "Findlaw Can I Refuse to Take Field Sobriety Tests?". Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 23.9 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Yen, Hope; Krisher, Tom (9 November 2021). "Congress Mandates New Car Technology to Stop Drunken Driving". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "A lower drink-drive limit in Scotland is not linked to reduced road traffic accidents as expected". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 10 September 2019. doi:10.3310/signal-000815. S2CID 241723380. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ Lewsey, Jim; Haghpanahan, Houra; Mackay, Daniel; McIntosh, Emma; Pell, Jill; Jones, Andy (June 2019). "Impact of legislation to reduce the drink-drive limit on road traffic accidents and alcohol consumption in Scotland: a natural experiment study". Public Health Research. 7 (12): 1–46. doi:10.3310/phr07120. ISSN 2050-4381. PMID 31241879. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

Further reading

- "Why drunk drivers may get behind the wheel." Mental Health Weekly Digest (2010). Web. 2 September 2010.

- Pages with obsolete Vega graphs

- Pages with graphs

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Use dmy dates from October 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2018

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from February 2021

- Driving under the influence

- Alcohol-related crimes

- Alcohol