Disability-adjusted life year

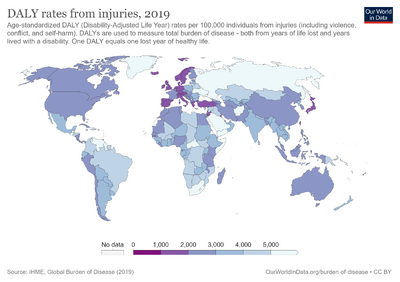

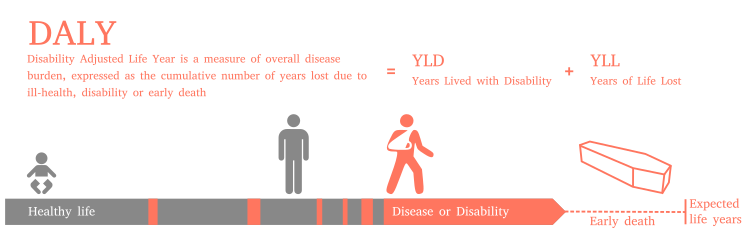

The disability-adjusted life year (DALY) is a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability or early death. It was developed in the 1990s as a way of comparing the overall health and life expectancy of different countries.

The DALY has become more common in the field of public health and health impact assessment (HIA). It not only includes the potential years of life lost due to premature death, but also includes equivalent years of 'healthy' life lost by virtue of being in states of poor health or disability. In so doing, mortality and morbidity are combined into a single, common metric.[2]

Calculation

The disability-adjusted life year is a societal measure of the disease or disability burden in populations. DALYs are calculated by combining measures of life expectancy as well as the adjusted quality of life during a burdensome disease or disability for a population. DALYs are related to the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) measure; however, QALYs only measure the benefit with and without medical intervention and therefore do not measure the total burden. Also, QALYs tend to be an individual measure, and not a societal measure.

Traditionally, health liabilities were expressed using one measure, the years of life lost (YLL) due to dying early. A medical condition that did not result in dying younger than expected was not counted. The burden of living with a disease or disability is measured by the years lost due to disability (YLD) component, sometimes also known as years lost due to disease or years lived with disability/disease.[2]

DALYs are calculated by taking the sum of these two components:[3]

- DALY = YLL + YLD

The DALY relies on an acceptance that the most appropriate measure of the effects of chronic illness is time, both time lost due to premature death and time spent disabled by disease. One DALY, therefore, is equal to one year of healthy life lost.

How much a medical condition affects a person is called the disability weight (DW). This is determined by disease or disability and does not vary with age. Tables have been created of thousands of diseases and disabilities, ranging from Alzheimer's disease to loss of finger, with the disability weight meant to indicate the level of disability that results from the specific condition.

| Condition | DW 2004[4] | DW 2010[5] |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's and other dementias | 0.666 | 0.666 |

| Blindness | 0.594 | 0.195 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.528 | 0.576 |

| AIDS, not on ART | 0.505 | 0.547 |

| Burns 20%–60% of body | 0.441 | 0.438 |

| Fractured femur | 0.372 | 0.308 |

| Moderate depression episode | 0.350 | 0.406 |

| Amputation of foot | 0.300 | 0.021–0.1674 |

| Deafness | 0.229 | 0.167–0.281 |

| Infertility | 0.180 | 0.026–0.056 |

| Amputation of finger | 0.102 | 0.030 |

| Lower back pain | 0.061 | 0.0322–0.0374 |

Examples of the disability weight are shown on the right. Some of these are "short term", and the long-term weights may be different.

The most noticeable change between the 2004 and 2010 figures for disability weights above are for blindness as it was considered the weights are a measure of health rather than well-being (or welfare) and a blind person is not considered to be ill. "In the GBD terminology, the term disability is used broadly to refer to departures from optimal health in any of the important domains of health."[6]

At the population level, the disease burden as measured by DALYs is calculated by adding YLL to YLD. YLL uses the life expectancy at the time of death.[7] YLD is determined by the number of years disabled weighted by level of disability caused by a disability or disease using the formula:

- YLD = I × DW × L

In this formula, I = number of incident cases in the population, DW = disability weight of specific condition, and L = average duration of the case until remission or death (years). There is also a prevalence (as opposed to incidence) based calculation for YLD. Number of years lost due to premature death is calculated by

- YLL = N × L

where N = number of deaths due to condition, L = standard life expectancy at age of death.[2] Note that life expectancies are not the same at different ages. For example, in Paleolithic era, life expectancy at birth was 33 years, but life expectancy at the age of 15 was an additional 39 years (total 54).[8]

Historically Japanese life expectancy statistics have been used as the standard for measuring premature death, as the Japanese have the longest life expectancies.[9] Other approaches have since emerged, include using national life tables for YLL calculations, or using the reference life table derived by the GBD study.[10][11]

Age weighting

The World Health Organization (WHO) used age weighting and time discounting at 3 percent in DALYs prior to 2010 but discontinued using them starting in 2010.[13]

There are two components to this differential accounting of time: age-weighting and time-discounting. Age-weighting is based on the theory of human capital. Commonly, years lived as a young adult are valued more highly than years spent as a young child or older adult, as these are years of peak productivity. Age-weighting receives considerable criticism for valuing young adults at the expense of children and the old. Some criticize, while others rationalize, this as reflecting society's interest in productivity and receiving a return on its investment in raising children. This age-weighting system means that somebody disabled at 30 years of age, for ten years, would be measured as having a higher loss of DALYs (a greater burden of disease), than somebody disabled by the same disease or injury at the age of 70 for ten years.

This age-weighting function is by no means a universal methodology in HALY studies, but is common when using DALYs. Cost-effectiveness studies using QALYs, for example, do not discount time at different ages differently.[14] This age-weighting function applies only to the calculation of DALYs lost due to disability. Years lost to premature death are determined from the age at death and life expectancy.

The Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) 2001–2002 counted disability adjusted life years equally for all ages, but the GBD 1990 and GBD 2004 studies used the formula[15]

[16] where is the age at which the year is lived and is the value assigned to it relative to an average value of 1.

In these studies, future years were also discounted at a 3% rate to account for future health care losses. Time discounting, which is separate from the age-weighting function, describes preferences in time as used in economic models.[17]

The effects of the interplay between life expectancy and years lost, discounting, and social weighting are complex, depending on the severity and duration of illness. For example, the parameters used in the GBD 1990 study generally give greater weight to deaths at any year prior to age 39 than afterward, with the death of a newborn weighted at 33 DALYs and the death of someone aged 5–20 weighted at approximately 36 DALYs.[18]

As a result of numerous discussions, by 2010 the World Health Organization had abandoned the ideas of age weighting and time discounting.[13] They had also substituted the idea of prevalence for incidence (when a condition started) because this is what surveys measure.

Economic applications

The methodology is not an economic measure. It measures how much healthy life is lost. It does not assign a monetary value to any person or condition, and it does not measure how much productive work or money is lost as a result of death and disease. However, HALYs, including DALYs and QALYs, are especially useful in guiding the allocation of health resources as they provide a common numerator, allowing for the expression of utility in terms of dollar/DALY, or dollar/QALY.[14] For example, in Gambia, provision of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine costs $670 per DALY saved.[19] This number can then be compared to other treatments for other diseases, to determine whether investing resources in preventing or treating a different disease would be more efficient in terms of overall health.

Examples

Schizophrenia has a 0.53 weighting and a broken femur a 0.37 weighting in the latest WHO weightings.[20]

Australia

Cancer (25.1/1,000), cardiovascular (23.8/1,000), mental problems (17.6/1,000), neurological (15.7/1,000), chronic respiratory (9.4/1,000) and diabetes (7.2/1,000) are the main causes of good years of expected life lost to disease or premature death.[21] Despite this, Australia has one of the longest life expectancies in the world.

Africa

These illustrate the problematic diseases and outbreaks occurring in 2013 in Zimbabwe, shown to have the greatest impact on health disability were typhoid, anthrax, malaria, common diarrhea, and dysentery.[22]

PTSD rates

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) DALY estimates from 2004 for the world's 25 most populous countries give Asian/Pacific countries and the United States as the places where PTSD impact is most concentrated (as shown here).

Noise-induced hearing loss

The disability-adjusted life years attributable to hearing impairment for noise-exposed U.S. workers across all industries was calculated to be 2.53 healthy years lost annually per 1,000 noise-exposed workers. Workers in the mining and construction sectors lost 3.45 and 3.09 healthy years per 1,000 workers, respectively. Overall, 66% of the sample worked in the manufacturing sector and represented 70% of healthy years lost by all workers.[23]

History and usage

Originally developed by Harvard University for the World Bank in 1990, the World Health Organization subsequently adopted the method in 1996 as part of the Ad hoc Committee on Health Research "Investing in Health Research & Development" report. The DALY was first conceptualized by Christopher J. L. Murray and Lopez in work carried out with the World Health Organization and the World Bank known as the Global Burden of Disease Study, which was published in 1990.[citation needed] It is now a key measure employed by the United Nations World Health Organization in such publications as its Global Burden of Disease.[24]

The DALY was also used in the 1993 World Development Report.[25]: x

Criticism

Both DALYs and QALYs are forms of HALYs, health-adjusted life years.

Some critics have alleged that DALYs are essentially an economic measure of human productive capacity for the affected individual.[26][irrelevant citation] In response, defenders of DALYs have argued that while DALYs have an age-weighting function that has been rationalized based on the economic productivity of persons at that age, health-related quality of life measures are used to determine the disability weights, which range from 0 to 1 (no disability to 100% disabled) for all disease. These defenders emphasize that disability weights are based not on a person's ability to work, but rather on the effects of the disability on the person's life in general. Hence, mental illness is one of the leading diseases as measured by global burden of disease studies, with depression accounting for 51.84 million DALYs. Perinatal conditions, which affect infants with a very low age-weight function, are the leading cause of lost DALYs at 90.48 million. Measles is fifteenth at 23.11 million.[14][27][28]

Some commentators have expressed doubt over whether the disease burden surveys (such as EQ-5D) fully capture the impacts of mental illness, due to factors including ceiling effects.[29][30][31]

According to Pliskin et al., the QALY model requires utility independent, risk neutral, and constant proportional tradeoff behaviour.[32] Because of these theoretical assumptions, the meaning and usefulness of the QALY is debated.[33][34] Perfect health is difficult, if not impossible, to define. Some argue that there are health states worse than being dead, and that therefore there should be negative values possible on the health spectrum (indeed, some health economists have incorporated negative values into calculations). Determining the level of health depends on measures that some argue place disproportionate importance on physical pain or disability over mental health.[35]

The method of ranking interventions on grounds of their cost per QALY gained ratio (or ICER) is controversial because it implies a quasi-utilitarian calculus to determine who will or will not receive treatment.[36] However, its supporters argue that since health care resources are inevitably limited, this method enables them to be allocated in the way that is approximately optimal for society, including most patients. Another concern is that it does not take into account equity issues such as the overall distribution of health states – particularly since younger, healthier cohorts have many times more QALYs than older or sicker individuals. As a result, QALY analysis may undervalue treatments which benefit the elderly or others with a lower life expectancy. Also, many would argue that all else being equal, patients with more severe illness should be prioritised over patients with less severe illness if both would get the same absolute increase in utility.[37]

As early as 1989, Loomes and McKenzie recommended that research be conducted concerning the validity of QALYs.[38] In 2010, with funding from the European Commission, the European Consortium in Healthcare Outcomes and Cost-Benefit Research (ECHOUTCOME) began a major study on QALYs as used in health technology assessment.[39] Ariel Beresniak, the study's lead author, was quoted as saying that it was the "largest-ever study specifically dedicated to testing the assumptions of the QALY".[40] In January 2013, at its final conference, ECHOUTCOME released preliminary results of its study which surveyed 1361 people "from academia" in Belgium, France, Italy and the UK.[40][41][42] The researchers asked the subjects to respond to 14 questions concerning their preferences for various health states and durations of those states (e.g., 15 years limping versus 5 years in a wheelchair).[42] They concluded that "preferences expressed by the respondents were not consistent with the QALY theoretical assumptions" that quality of life can be measured in consistent intervals, that life-years and quality of life are independent of each other, that people are neutral about risk, and that willingness to gain or lose life-years is constant over time.[42] ECHOUTCOME also released "European Guidelines for Cost-Effectiveness Assessments of Health Technologies", which recommended not using QALYs in healthcare decision making.[43] Instead, the guidelines recommended that cost-effectiveness analyses focus on "costs per relevant clinical outcome".[40][43]

In response to the ECHOUTCOME study, representatives of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Scottish Medicines Consortium, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development made the following points. First, QALYs are better than alternative measures.[40][41] Second, the study was "limited".[40][41] Third, problems with QALYs were already widely acknowledged.[41] Fourth, the researchers did not take budgetary constraints into consideration.[41] Fifth, the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence uses QALYs that are based on 3395 interviews with residents of the UK, as opposed to residents of several European countries.[40] Finally, people who call for the elimination of QALYs may have "vested interests".[40]

See also

- Bhutan GNH Index

- Broad measures of economic progress

- Disease burden

- Economics

- Full cost accounting

- Green national product

- Green gross domestic product (Green GDP)

- Gender-related Development Index

- Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI)

- Global burden of disease

- Global Peace Index

- Gross National Happiness

- Gross National Well-being (GNW)

- Happiness economics

- Happy Planet Index (HPI)

- Human Development Index (HDI)

- ISEW (Index of sustainable economic welfare)

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)

- Progress (history)

- Progressive utilization theory

- Legatum Prosperity Index

- Leisure satisfaction

- Living planet index

- Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

- Money-rich, time-poor

- Post-materialism

- Psychometrics

- Subjective life satisfaction

- Where-to-be-born Index

- Wikiprogress

- World Values Survey (WVS)

- World Happiness Report

- Quality-adjusted life year (QALY)

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Healthy Life Years

- Happiness economics

- Seven Ages of Man

References

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-11-11. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "WHO | Metrics: Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY)". WHO. Archived from the original on 2019-11-27. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ↑ Havelaar, Arie (August 2007). "Methodological choices for calculating the disease burden and cost-of-illness of foodborne zoonoses in European countries" (PDF). Med-Vet-Net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "GLOBAL BURDEN OF DISEASE 2004 UPDATE: DISABILITY WEIGHTS FOR DISEASES AND CONDITIONS" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-30. Retrieved Jul 25, 2016.

- ↑ WHO 2013.

- ↑ WHO 2013, p. 15.

- ↑ Martinez, Ramon; Soliz, Patricia; Caixeta, Roberta; Ordunez, Pedro (9 January 2019). "Reflection on modern methods: years of life lost due to premature mortality—a versatile and comprehensive measure for monitoring non-communicable disease mortality". International Journal of Epidemiology. 48 (4): 1367–1376. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy254. PMC 6693813. PMID 30629192.

- ↑ Kaplan, Hillard; Hill, Kim; Lancaster, Jane; Hurtado, A. Magdalena (2000). "A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence, and longevity". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 9 (4): 156–185. doi:10.1002/1520-6505(2000)9:4<156::AID-EVAN5>3.0.CO;2-7. S2CID 2363289.

- ↑ Menken M, Munsat TL, Toole JF (March 2000). "The global burden of disease study: implications for neurology". Arch. Neurol. 57 (3): 418–20. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.660.4176. doi:10.1001/archneur.57.3.418. PMID 10714674.

- ↑ Devleesschauwer B, McDonald SA, Speybroeck N, Wyper GM (2020). "Valuing the years of life lost due to COVID-19: the differences and pitfalls". International Journal of Public Health. 65 (6): 719–720. doi:10.1007/s00038-020-01430-2. PMC 7370635. PMID 32691080.

- ↑ Wyper GM, Devleesschauwer B, Mathers CD, McDonald SA, Speybroeck N (2022). "Years of life lost methods must remain fully equitable and accountable". European Journal of Epidemiology. 37 (2): 215–216. doi:10.1007/s10654-022-00846-9. PMC 8894819. PMID 35244840.

- ↑ Murray, Christopher J (1994). "Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 72 (3): 429–45. PMC 2486718. PMID 8062401.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "WHO methods and data sources for global burden of disease estimates 2000–2011" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-09. Retrieved Jul 27, 2016.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Gold, MR; Stevenson, D; Fryback, DG (2002). "HALYS and QALYS and DALYS, oh my: similarities and differences in summary measures of population health". Annual Review of Public Health. 23: 115–34. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140513. PMID 11910057.

- ↑ "WHO | Disability weights, discounting and age weighting of DALYs". WHO. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ↑ Prüss-Üstün, A.; Mathers, C.; Corvalán, C.; Woodward, A. (2003). "3 The Global Burden of Disease concept". Introduction and methods: Assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. Environmental burden of disease. Vol. 1. World Health Organization. ISBN 978-9241546201. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-01.

- ↑ Kramer, Alexander; Hossain, Mobarak; Kraas, Frauke (2011). Health in megacities and urban areas. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7908-2732-3.

- ↑ Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Lopez AD (2007). "Measuring the burden of neglected tropical diseases: the global burden of disease framework". PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 1 (2): e114. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000114. PMC 2100367. PMID 18060077.

- ↑ Kim, SY; Lee, G; Goldie, SJ (Sep 3, 2010). "Economic evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in The Gambia". BMC Infectious Diseases. 10: 260. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-260. PMC 2944347. PMID 20815900.

- ↑ "Global burden of disease 2004 update: disability weights for diseases and conditions" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-30. Retrieved 2016-07-25.

- ↑ Chant, Kerry (November 2008). "The Health of the People of New South Wales (summary report)" (PDF). Chief Health Officer, Government of New South Wales. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-21. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Zimbabwe, Ministry of Health and Child Welfare (December 2013). "Zimbabwe Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin" (PDF). World Health Organization, Government of Zimbabwe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-28. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Masterson, EA; Bushnell, PT; Themann, CL; Morata, TC (2016). "Hearing Impairment Among Noise-Exposed Workers — United States, 2003–2012". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 65 (15): 389–394. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6515a2. PMID 27101435.

- ↑ "Global Health Estimates". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2015-08-31.

- ↑ World Bank (1993). World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2016-11-27.

- ↑ Thacker SB, Stroup DF, Carande-Kulis V, Marks JS, Roy K, Gerberding JL (2006). "Measuring the public's health". Public Health Rep. 121 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1177/003335490612100107. PMC 1497799. PMID 16416694.

- ↑ Kramer, Alexander, Md. Mobarak Hossain Khan, Frauke Kraas (2011). Health in megacities and urban areas. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7908-2732-3.

- ↑ Murray CJ (1994). "Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years". Bull World Health Organ. 72 (3): 429–445. PMC 2486718. PMID 8062401.

- ↑ Papaioannou, Diana; Brazier, John; Parry, Glenys (1 September 2011). "How Valid and Responsive Are Generic Health Status Measures, such as EQ-5D and SF-36, in Schizophrenia? A Systematic Review". Value in Health. 14 (6): 907–920. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.006. PMC 3179985. PMID 21914513. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ Brazier, John (2010). "Is the EQ–5D fit for purpose in mental health?" (PDF). The British Journal of Psychiatry. 197 (5): 348–349. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082453. PMID 21037210. S2CID 902903. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Saarni, Samuli I.; Viertiö, Satu; Perälä, Jonna; Koskinen, Seppo; Lönnqvist, Jouko; Suvisaari, Jaana (2010). "Quality of life of people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychotic disorders". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 197 (5): 386–394. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076489. PMID 21037216. S2CID 4676470. Archived from the original on 2016-01-29.

- ↑ Pliskin, J. S.; Shepard, D. S.; Weinstein, M. C. (1980). "Utility Functions for Life Years and Health Status". Operations Research. 28 (1): 206–24. doi:10.1287/opre.28.1.206. JSTOR 172147.

- ↑ Prieto, Luis; Sacristán, José A (2003). "Problems and solutions in calculating quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 1: 80. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-80. PMC 317370. PMID 14687421.

- ↑ Mortimer, D.; Segal, L. (2007). "Comparing the Incomparable? A Systematic Review of Competing Techniques for Converting Descriptive Measures of Health Status into QALY-Weights". Medical Decision Making. 28 (1): 66–89. doi:10.1177/0272989X07309642. PMID 18263562. S2CID 40830765.

- ↑ Dolan, P. (January 2008). "Developing methods that really do value the 'Q' in the QALY" (PDF). Health Economics, Policy and Law. 3 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1017/S1744133107004355. PMID 18634633. S2CID 25353890. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-03. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ↑ Schlander, Michael (2010-05-23), Measures of efficiency in healthcare: QALMs about QALYs? (PDF), Institute for Innovation & Valuation in Health Care, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-14, retrieved 2010-05-23

- ↑ Nord, Erik; Pinto, Jose Luis; Richardson, Jeff; Menzel, Paul; Ubel, Peter (1999). "Incorporating societal concerns for fairness in numerical valuations of health programmes". Health Economics. 8 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199902)8:1<25::AID-HEC398>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 10082141.

- ↑ Loomes, Graham; McKenzie, Lynda (1989). "The use of QALYs in health care decision making". Social Science & Medicine. 28 (4): 299–308. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(89)90030-0. ISSN 0277-9536. PMID 2649989.

- ↑ "ECHOUTCOME: European Consortium in Healthcare Outcomes and Cost-Benefit Research". Archived from the original on 2016-10-08.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 Holmes, David (March 2013). "Report triggers quibbles over QALYs, a staple of health metrics". Nature Medicine. 19 (3): 248. doi:10.1038/nm0313-248. PMID 23467219.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 Dreaper, Jane (24 January 2013). "Researchers claim NHS drug decisions 'are flawed'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2017-03-20. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Beresniak, Ariel; Medina-Lara, Antonieta; Auray, Jean Paul; De Wever, Alain; Praet, Jean-Claude; Tarricone, Rosanna; Torbica, Aleksandra; Dupont, Danielle; Lamure, Michel; Duru, Gerard (2015). "Validation of the Underlying Assumptions of the Quality-Adjusted Life-Years Outcome: Results from the ECHOUTCOME European Project". PharmacoEconomics. 33 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1007/s40273-014-0216-0. ISSN 1170-7690. PMID 25230587. S2CID 5392762.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 European Consortium in Healthcare Outcomes and Cost-Benefit Research (ECHOUTCOME). "European Guidelines for Cost-Effectiveness Assessments of Health Technologies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-08-14.

External links

- WHO Definition Archived 2013-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2016

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from July 2016

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Global health

- Health economics

- World Health Organization