Diphtheria vaccine

DTP vaccine | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Corynebacterium diphtheriae |

| Type | Toxoid |

| Clinical data | |

| Routes of use | Injection into muscle |

| External links | |

| MedlinePlus | a607027 |

Diphtheria vaccine is a vaccine against Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the bacteria that causes diphtheria.[1] It is used in children and adults in one of two strengths; the higher dose of diphtheria toxoid 'D', for very young children, and the lower dose of diphtheria toxoid 'd', for older children, adults and for boosters.[2] Its use has resulted in a more than 90% decrease in number of cases globally between 1980 and 2000.[3]

Vaccinating against diphtheria is recommended for all children.[4] The first dose is recommended at six to eight weeks of age with two additional doses four weeks apart, after which it is about 95% effective during childhood.[3] Three further doses are recommended during childhood.[3] If travelling to an area with a risk of diphtheria, a booster dose may be needed.[5] It is recommended in women in the later part of each pregnancy and in any unimmunized close contacts of the baby.[6] It is unclear if further doses later in life are needed.[3]

The diphtheria vaccine is very safe.[3] Significant side effects are rare.[3] Pain may occur at the injection site.[3] A bump may form at the site of injection that lasts a few weeks.[7] The vaccine is safe in both pregnancy and among those who have a poor immune function.[7]

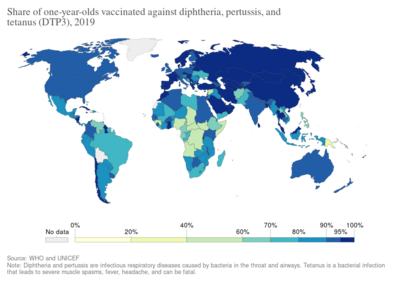

It is not available as a single vaccine.[5] All diphtheria vaccines are given combined with tetanus vaccine (Td and DT vaccines).[8] It can be given with other vaccines in a variety of further combinations, including as DTP vaccine or DTaP with pertussis vaccine, and other combinations with inactivated polio vaccine, Hib vaccine and hepatitis B vaccine.[3] The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended its use since 1974.[3] About 84% of the world population is vaccinated.[9] It is given as an intramuscular injection.[3] The vaccine needs to be kept cold but not frozen.[7]

The diphtheria vaccine was developed in 1923.[10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11] The wholesale price in the developing world of a version that contains tetanus toxoid is between 0.12 and 0.99 USD per dose as of 2014.[12] In the United States it is less than 25 USD.[13]

Medical uses

Vaccines that contain diphtheria vaccine are used to protect against Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the bacteria that causes diphtheria.[2] About 95% of people vaccinated develop immunity, and vaccination against diphtheria has resulted in a more than 90% decrease in number of cases globally between 1980 and 2000.[3] About 86% of the world population was vaccinated as of 2016.[9]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established.[14]

Recommendations

The World Health Organization has recommended vaccination against diphtheria since 1974.[3] The first dose is recommended at six weeks of age with two additional doses four weeks apart, after receiving these three doses about 95% of people are immune.[3] Three further doses are recommended during childhood.[3] Booster doses every ten years are no longer recommended if this vaccination scheme of 3 doses + 3 booster doses is followed.[3] Injection of 3 doses + 1 booster dose, provides immunity for 25 years after the last dose.[3] If only three initial doses are given, booster doses are needed to ensure continuing protection.[3]

Side effects

Severe side effects from diphtheria toxoid are rare.[3] Pain may occur at the injection site.[3] A bump may form at the site of injection that lasts a few weeks.[7] The vaccine is safe during pregnancy and among those who have a poor immune function.[7] DTP vaccines may cause additional adverse effects such as fever, irritability, drowsiness, loss of appetite, and, in 6–13% of vaccine recipients, vomiting.[3] Severe adverse effects of DTP vaccines include fever over 40.5 °C/104.9 °F (1 in 333 doses), febrile seizures (1 in 12,500 doses), and hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes (1 in 1,750 doses).[3][15] Side effects of DTaP vaccines are similar but less frequent.[3] Tetanus toxoid containing vaccines (Td, DT, DTP and DTaP) may cause brachial neuritis at a rate of 0.5 to 1 case per 100,000 toxoid recipients.[16][17]

Types

The diphtheria vaccine is a diphtheria toxoid produced after formaldehyde is added to a purified toxin extracted from a strain of C. diphtheriae. This is adsorbed on to an adjuvant; aluminium phosphate or aluminium hydroxide. Two strengths are available; the higher dose of diphtheria toxoid 'D', used in young children, and the lower dose of diphtheria toxoid 'd', for those aged over 10 years and for boosters.[2]

Higher dose diphtheria toxoid

-

DT-vaccine (diphtheria and tetanus).[18]

-

Infanrix hexa (DTaP-HepB-IPV-Hib) used in the UK for primary immunisation in young children

Lower dose diphtheria toxoid

-

REVAXiS (Td/IPV): diphtheria, tetanus, and polio for age >10 years.[19]

-

REPEVAX (dTaP/IPV), for use from 3 years of age as a booster following primary immunization and for passive protection against pertussis in early infancy following maternal immunization[20]

-

Boostrix-IPV (dTaP/IPV): for booster vaccination against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio from the age of three years, and in pregnant women to protect the baby in early infancy.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ "Diphtheria Vaccination". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ramsey, Mary, ed. (2013). "15. Diphtheria". The Green Book; Immunisation against infectious diseases (PDF). UK Health Security Agency, Department of Health & Social Care. pp. 109–125. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 "Diphtheria vaccine: WHO position paper- August 2017" (PDF). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 92 (31): 417–435. 4 August 2017. hdl:10665/258681. PMID 28776357. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ↑ Lampiris, Harry W.; maddix, Daniel S. (2020). "Appendix: Vaccines, immune globulins, and other complex biologic products". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1228. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "14. Vaccines". British National Formulary (BNF) (82 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2021 – March 2022. pp. 1357–1377. ISBN 978-0-85711-413-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ "Why should I get Tdap during pregnancy?". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Atkinson, William (May 2012). Diphtheria Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12 ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 215–230. ISBN 9780983263135. Archived from the original on 2016-09-15.

- ↑ Domachowske, Joseph (2021). "10. Diphtheria". In Domachowske, Joseph; Suryadevara, Manika (eds.). Vaccines: A Clinical Overview and Practical Guide. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 131–142. ISBN 978-3-030-58416-0. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Diphtheria". World Health Organization (WHO). 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ Macera, Caroline (2012). Introduction to Epidemiology: Distribution and Determinants of Disease. Nelson Education. p. 251. ISBN 9781285687148. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Vaccine, Diphtheria-Tetanus". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 313. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Braun, M. Miles; DuVernoy, Tracy S.; et al. (The VAERS Working Group) (October 2000). "Hypotonic–Hyporesponsive Episodes Reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 1996–1998". Pediatrics. 106 (4): e52. doi:10.1542/peds.106.4.e52. PMID 11015547. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ "Tetanus". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 April 2019. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ↑ Health, Australian Government Department of (10 October 2017). "Immunisation". Australian Government Department of Health. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ↑ "About Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis Vaccination | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ↑ "REVAXIS suspension for injection in pre-filled syringe - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ "REPEVAX - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ "Boostrix-IPV suspension for injection in pre-filled syringe - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- "Infanrix". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Daptacel". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Diphtheria Toxoid at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Diphtheria Vaccine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: date format

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugs with no legal status

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugs that are a vaccine

- Chemicals that do not have a ChemSpider ID assigned

- Diphtheria

- 1923 in biology

- Toxoid vaccines

- Vaccines

- World Health Organization essential medicines (vaccines)

- RTT

- RTTVaccine

![DT-vaccine (diphtheria and tetanus).[18]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/DT-vaccine.jpg/250px-DT-vaccine.jpg)

![REVAXiS (Td/IPV): diphtheria, tetanus, and polio for age >10 years.[19]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/REVAXiS_%28UK%29.jpg/250px-REVAXiS_%28UK%29.jpg)

![REPEVAX (dTaP/IPV), for use from 3 years of age as a booster following primary immunization and for passive protection against pertussis in early infancy following maternal immunization[20]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/REPEVAX_vaccine_in_pre-filled_syringe.jpg/250px-REPEVAX_vaccine_in_pre-filled_syringe.jpg)

![Boostrix-IPV (dTaP/IPV): for booster vaccination against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio from the age of three years, and in pregnant women to protect the baby in early infancy.[21]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Boostrix-IPV_vaccine.jpg/250px-Boostrix-IPV_vaccine.jpg)