Dientamoebiasis

| Dientamoebiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Dientamoebiases | |

| |

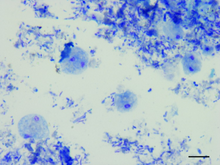

| Dientamoeba fragilis, in a specimen prepared using the Kohn stain | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | None, abdominal pain, diarrhea[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Stool samples |

| Treatment | Iodoquinol, doxycycline, metronidazole, paromomycin, secnidazole |

| Frequency | 10% 11–15 years 11.5% 16–20 years 0.3–1.9% over 20 years |

Dientamoebiasis is a medical condition caused by infection with Dientamoeba fragilis, a single-cell parasite that infects the lower gastrointestinal tract. It is an important cause of traveler's diarrhea, chronic abdominal pain, chronic fatigue, and failure to thrive in children.[3][1][4]

Children are more commonly affected than adults.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptoms are abdominal pain (69%) and diarrhea (61%).[5] Diarrhea may be intermittent and may not be present in all cases. It is often chronic, lasting over two weeks. The degree of symptoms may vary from asymptomatic to severe,[6] and can include weight loss, vomiting, fever, and involvement of other digestive organs.

Symptoms may be more severe in children. Additional symptoms reported have included:[7][2]

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

- Urticaria (hives)

- Pruritus (itchiness)

- Biliary infection

Cause

Genetic diversity

As many individuals are asymptomatic carriers of D. fragilis, pathogenic and nonpathogenic variants are proposed to exist. D. fragilis isolates from 60 people with symptomatic infection in Sydney, Australia, found all were infected with the same genotype,[8] which is the most common worldwide, but differed from the genotype first described from a North American isolate and later also detected in Europe.[9]

Transmission

Organisms similar to D. fragilis are known to produce a cyst stage that is able to survive outside the host and facilitate infection of new hosts. However, the exact manner in which it is transmitted is not yet known, as the organism is unable to survive outside its human host for more than a few hours after excretion, and no cyst stage has been found.[10]

Early theories of transmission suggested D. fragilis was unable to produce a cyst stage in infected humans, but some animal existed that in which it did produce a cyst stage, and this animal was responsible for spreading it. However, no such animal has ever been discovered.[7] A later theory suggested the organism was transmitted by pinworms, which provided protection for the parasite outside the host. DNA has been detected in surface-sterilized eggs of Enterobius vermicularis eggs, thus suggesting the latter may harbor the former.[11] Experimental ingestion of pinworm eggs established infection in two investigators. Numerous studies reported high rates of coinfection with helminthes.[12] However, recent study has failed to show any association between D. fragilis infection and pinworm infection. Parasites similar to D. fragilis are transmitted by consuming water or food contaminated with feces.[10]

-

Dientamoeba fragilis

-

Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites

-

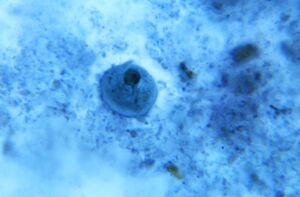

Binucleate form of a trophozoite D. fragilis

Mechanism

D. fragilis replicates by binary fission, moves by pseudopodia, and feeds by phagocytosis. The cytoplasm typically contains numerous food vacuoles that contain ingested debris, including bacteria. Waste materials are eliminated from the cell through digestive vacuoles by exocytosis. D. fragilis possesses some flagellate characteristics. In the binucleated form is a spindle structure located between the nuclei, which stems from certain polar configurations adjacent to a nucleus; these configurations appear to be homologous to hypermastigotes’ atractophores. A complex Golgi apparatus is seen; the nuclear structure of D. fragilis is more similar to that of flagellated trichomonads than to that of Entamoeba. Also notable is the presence of hydrogenosomes, which are also a characteristic of other trichomonads.[13]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually performed by submitting multiple stool samples for examination by a parasitologist in a procedure known as an ova and parasite examination. A percentage of those infected with D. fragilis infection exhibit peripheral blood eosinophilia.[14][15]

A minimum of three stool specimens having been immediately fixed in polyvinyl alcohol fixative, sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin fixative, or Schaudinn's fixative should be submitted, as the protozoan does not remain morphologically identifiable for long. All specimens, regardless of consistency, are permanently stained prior to microscopic examination with an oil immersion lens. The disease may remain cryptic due to the lack of a cyst stage if these recommendations are not followed.[16]

The trophozoite forms have been recovered from formed stool, thus the need to perform the ova and parasite examination on specimens other than liquid or soft stools. DNA fragment analysis provides excellent sensitivity and specificity when compared to microscopy for the detection of D. fragilis and both methods should be employed in laboratories with PCR capability. The most sensitive detection method is parasite culture, and the culture medium requires the addition of rice starch.[4][17][18]

An indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) for fixed stool specimens has been developed.[19]

- One researcher investigated the phenomenon of symptomatic relapse following treatment of infection with D. fragilis in association with its apparent disappearance from stool samples. The organism could still be detected in patients through colonoscopy or by examining stool samples taken in conjunction with a saline laxative.[20]

- A study found that trichrome staining, a traditional method for identification, had a sensitivity of 36% (9/25) when compared to stool culture.[21]

- An additional study found that the sensitivity of staining was 50% (2/4), and that the organism could be successfully cultured in stool specimens up to 12-hours old that were kept at room temperature.[22]

Treatment

Concomitant pinworm infection should also be excluded, although the association has not been proven. Successful treatment of the infection with iodoquinol, doxycycline, metronidazole, paromomycin, and secnidazole has been reported.[7][6]

Resistance requires the use of combination therapy to eradicate the organism. All persons living in the same residence should be screened for D. fragilis, as asymptomatic carriers may provide a source of repeated infection. Paromomycin is an effective prophylactic for travellers who will encounter poor sanitation and unsafe drinking water.[23][7][6]

Epidemiology

Rates of infection increase in conditions of crowding and poor sanitation, and are higher in military personnel and mental institutions. The true extent of disease has yet to emerge, as most laboratories do not use techniques to adequately identify this organism. An Australian study identified a large number of patients, considered to have irritable bowel syndrome, who were actually infected with Dientamoeba fragilis.[24]

Although D. fragilis has been described as an infection "emerging from obscurity",[7] it has become one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal infections in industrialized countries, especially among children and young adults. A Canadian study reported a prevalence of around 10% in boys and girls aged 11–15 years,[10] a prevalence of 11.5% in individuals aged 16–20, and a lower incidence of 0.3–1.9% in individuals over age 20.

History

Early microbiologists reported that the organism was not pathogenic, though six of the seven individuals from whom they isolated it were experiencing symptoms of dysentery. Their report, published in 1918, concluded the organism was not pathogenic because it consumed bacteria in culture, but did not appear to engulf red blood cells, as was seen in the best-known disease-causing amoeba of the time, Entamoeba histolytica. This initial report may still be contributing to the reluctance of physicians to diagnose the infection.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 van Gestel, Rosanne Sfe; Kusters, Johannes G.; Monkelbaan, Jan F. (August 2019). "A clinical guideline on Dientamoeba fragilis infections". Parasitology. 146 (9): 1131–1139. doi:10.1017/S0031182018001385. ISSN 1469-8161. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "CDC - DPDx - Dientamoeba fragilis Infection". www.cdc.gov. 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ↑ "Dientamoeba Fragilis Infection: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Medscape. 30 December 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Stark, Damien J.; Beebe, Nigel; Marriott, Deborah; Ellis, John T.; Harkness, John (February 2006). "Dientamoebiasis: clinical importance and recent advances". Trends in Parasitology. 22 (2): 92–96. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2005.12.001. ISSN 1471-4922. PMID 16380293. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ Vandenberg O, Peek R, Souayah H, et al. (2006). "Clinical and microbiological features of dientamoebiasis in patients suspected of suffering from a parasitic gastrointestinal illness: a comparison of Dientamoeba fragilis and Giardia lamblia infections". Int. J. Infect. Dis. 10 (3): 255–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2005.05.011. PMID 16469517.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Norberg A, Nord CE, Evengård B (2003). "Dientamoeba fragilis—a protozoal infection that may cause severe bowel distress". Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 9 (1): 65–8. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00459.x. PMID 12691546.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Johnson EH, Windsor JJ, Clark CG (2004). "Emerging from obscurity: biological, clinical, and diagnostic aspects of Dientamoeba fragilis". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17 (3): 553–70, table of contents. doi:10.1128/CMR.17.3.553-570.2004. PMC 452553. PMID 15258093.

- ↑ Stark D, Beebe N, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J (2005). "Prospective study of the prevalence, genotyping, and clinical relevance of Dientamoeba fragilis infections in an Australian population" (PDF). J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 (6): 2718–23. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.6.2718-2723.2005. PMC 1151954. PMID 15956388. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-02-18. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ↑ Johnson JA, Clark CG (2000). "Cryptic genetic diversity in Dientamoeba fragilis". J. Clin. Microbiol. 38 (12): 4653–4654. doi:10.1128/JCM.38.12.4653-4654.2000. PMC 87656. PMID 11101615.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Lagacé-Wiens PR, VanCaeseele PG, Koschik C (2006). "Dientamoeba fragilis: an emerging role in intestinal disease". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 175 (5): 468–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060265. PMC 1550747. PMID 16940260.

- ↑ Ogren J, Dienus O, Löfgren S, Iveroth P, Matussek A (2013). "Dientamoeba fragilis DNA detection in Enterobius vermicularis eggs". Pathogens and Disease. 69 (2): 157–8. doi:10.1111/2049-632X.12071. PMC 3908373. PMID 23893951.

- ↑ Bottone, Edward J. (17 January 2006). Atlas of the Clinical Microbiology of Infectious Diseases: Viral, Fungal and Parasitic Agents. CRC Press. ISBN 9781842142400 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Tachezy, Jan (2010). Hydrogenosomes and mitosomes: mitochondria of anaerobic eukaryotes. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-09542-9.

- ↑ Prevention, CDC-Centers for Disease Control and (17 September 2020). "CDC - Dientamoeba fragilis - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ↑ Hill, David R.; Nash, Theodore E. (1 January 2011). "CHAPTER 93 - Intestinal Flagellate and Ciliate Infections". Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice (Third Edition). W.B. Saunders. pp. 623–632. ISBN 978-0-7020-3935-5. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ↑ Grendon JH, Digiacomo RF, Frost FJ (1991). "Dientamoeba fragilis detection methods and prevalence: a survey of state public health laboratories". Public Health Rep. 106 (3): 322–5. PMC 1580247. PMID 1905055.

- ↑ Garcia, Lynne S. (September 2016). "Dientamoeba fragilis, One of the Neglected Intestinal Protozoa". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 54 (9): 2243–2250. doi:10.1128/JCM.00400-16. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ↑ Liu, Dongyou (5 July 2012). Molecular Detection of Human Parasitic Pathogens. CRC Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4398-1242-6. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ↑ Procop, Gary W.; Church, Deirdre L.; Hall, Geraldine S.; Janda, William M. (1 July 2020). Koneman's Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 1440. ISBN 978-1-284-32237-8. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ↑ Steinitz H, Talis B, Stein B (1970). "Entamoeba histolytica and Dientamoeba fragilis and the syndrome of chronic recurrent intestinal amoebiasis in Israel". Digestion. 3 (3): 146–53. doi:10.1159/000197025. PMID 4317789.

- ↑ Windsor JJ, Macfarlane L, Hughes-Thapa G, Jones SK, Whiteside TM (2003). "Detection of Dientamoeba fragilis by culture". Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 60 (2): 79–83. doi:10.1080/09674845.2003.11783678. PMID 12866914. S2CID 3530597.

- ↑ Sawangjaroen N, Luke R, Prociv P (1993). "Diagnosis by faecal culture of Dientamoeba fragilis infections in Australian patients with diarrhoea". Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87 (2): 163–5. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(93)90472-3. PMID 8337717.

- ↑ Nagata, Noriyuki; Marriott, Deborah; Harkness, John; Ellis, John T.; Stark, Damien (1 December 2012). "Current treatment options for Dientamoeba fragilis infections". International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance. 2: 204–215. doi:10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.08.002. ISSN 2211-3207. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ↑ Borody T, Warren E, Wettstein A, et al. (2002). "Eradication of Dientamoeba fragilis can resolve IBS-like symptoms". J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17 (Suppl): A103. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02681.x. PMID 11895561. S2CID 37118600.

External links

- Dientamoeba Fragilis Infection~treatment at eMedicine

- [1] Archived 2013-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |