Gastroparesis

| Gastroparesis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Delayed gastric emptying | |

| |

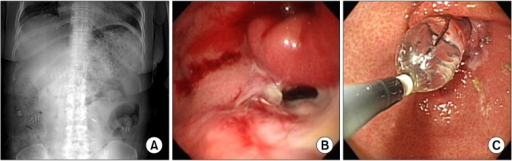

| X-ray showing a large amount of food in the stomach due to severe gastroparesis[1] | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Nausea, vomiting, heartburn, bloating, feeling full.[3] |

| Complications | Dehydration, malnutrition, weight loss, poor blood sugar control, bezoars[4] |

| Causes | Unknown, diabetes, certain medications, injury to the vagus nerve, low thyroid, scleroderma, gastroenteritis, radiation therapy[3][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Upper GI endoscopy, gastric emptying scan, gastric emptying breath test, wireless motility capsule[6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Functional dyspepsia, rumination syndrome, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, cyclic vomiting syndrome, gastric outlet obstruction[5][7] |

| Treatment | Dietary changes, medications to stimulate stomach emptying, medications to reduce vomiting, feeding tube, surgery[8] |

| Frequency | ~2.5 per 10,000[4] |

Gastroparesis, also called delayed gastric emptying, is a disorder that results in slow movement of food from the stomach to small intestines.[4] Symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, heartburn, bloating, and feeling full.[3] Complications may include dehydration, malnutrition, weight loss, poor blood sugar control, and bezoars.[4]

The cause may be unknown or include diabetes, certain medications, injury to the vagus nerve, low thyroid, scleroderma, gastroenteritis, or radiation therapy.[3][5] Medications that may be involved include opioids, anticholinergics, and some antidepressants.[3] The underlying mechanism involves poor contraction of the stomach muscles.[4] Diagnosis may be supported by upper GI endoscopy, gastric emptying scan, gastric emptying breath test, or wireless motility capsule.[6][5]

Treatment includes dietary changes, medications to stimulate stomach emptying, medications to reduce vomiting, a feeding tube, or surgery.[8] Dietary changes may include small frequent low fat meals.[8] Medications to stimulate stomach emptying may include metoclopramide or domperidone.[8] Surgery may involve a venting gastrostomy or gastric electrical stimulation.[8]

Gastroparesis is diagnosed in about 1 in 10,000 males and 4 in 10,000 females.[4] However, nearly 2% of people have symptoms and it is believed many go undiagnosed.[5] The ability to measure flow through the stomach was developed during the 1900s.[9] The term "gastroparesis" came into use in 1958.[10] It is from Ancient Greek γαστήρ - gaster, meaning "stomach"; and -paresis, πάρεσις - meaning "partial paralysis".[11]

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptoms of gastroparesis are the following:[12]

- Chronic nausea

- Vomiting (especially of undigested food)

- Abdominal pain

- A feeling of fullness after eating just a few bites

Other symptoms include the following:

- Abdominal bloating

- Body aches (myalgia)

- Erratic blood glucose levels

- Acid reflux (GERD)

- Heartburn

- Lack of appetite

- Morning nausea

- Muscle weakness

- Night sweats

- Palpitations

- Spasms of the stomach wall

- Constipation or infrequent bowel movements

- Weight loss, malnutrition

Vomiting may not occur in all cases, as sufferers may adjust their diets to include only small amounts of food.[13]

Complications

Complications of gastroparesis include:

- Fluctuations in blood glucose due to unpredictable digestion times due to changes in rate and amount of food passing into the small bowel. This makes diabetes worse, but does not cause diabetes. Lack of control of blood sugar levels will make the gastroparesis worsen.[14]

- General malnutrition due to the symptoms of the disease (which frequently include vomiting and reduced appetite) as well as the dietary changes necessary to manage it. This is especially true for vitamin deficiencies such as scurvy because of inability to tolerate fresh fruits.[15]

- Severe fatigue and weight loss due to calorie deficit[14]

- Intestinal obstruction due to the formation of bezoars (solid masses of undigested food). This can cause nausea and vomiting, which can in turn be life threatening if they prevent food from passing the small intestine.[14]

- Small intestine bacterial overgrowth is commonly found in patients with gastroparesis.[16]

- Bacterial infection due to overgrowth in undigested food[14]

- A decrease in quality of life, since it can make keeping up with work and other responsibilities more difficult.[14]

Causes

Transient gastroparesis may arise in acute illness of any kind, as a consequence of certain cancer treatments or other drugs which affect digestive action, or due to abnormal eating patterns. The symptoms are almost identical to those of low stomach acid, therefore most doctors will usually recommend trying out supplemental hydrochloric acid before moving on to the invasive procedures required to confirm a damaged nerve.[17] Patients with cancer may develop gastroparesis because of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, immunosuppression followed by viral infections involving the GI tract, procedures such as celiac blocks, paraneoplastic neuropathy or myopathy, or after an allogeneic bone marrow transplant via graft-versus-host disease.[18]

Gastroparesis present similar symptoms to slow gastric emptying caused by certain opioid medications, antidepressants, and allergy medications, along with high blood pressure. For patients already with gastroparesis, these can make the condition worse.[19] More than 50% of all gastroparesis cases are idiopathic in nature, with unknown causes. It is, however, frequently caused by autonomic neuropathy. This may occur in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, about 30-50% among long-standing diabetics.[20] In fact, diabetes mellitus has been named as the most common cause of gastroparesis, as high levels of blood glucose may effect chemical changes in the nerves.[21] The vagus nerve becomes damaged by years of high blood glucose or insufficient transport of glucose into cells resulting in gastroparesis.[22] Adrenal and thyroid gland problems could also be a cause.[23]

Gastroparesis has also been associated with connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, and neurological conditions such as Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy.[24] It may occur as part of a mitochondrial disease. Opioids and anticholinergic medications can cause medication-induced gastroparesis. Chronic gastroparesis can be caused by other types of damage to the vagus nerve, such as abdominal surgery.[25] Heavy cigarette smoking is also a plausible cause since smoking causes damage to the stomach lining. Idiopathic gastroparesis (gastroparesis with no known cause) accounts for a third of all chronic cases; it is thought that many of these cases are due to an autoimmune response triggered by an acute viral infection.[22] Gastroenteritis, mononucleosis, and other ailments have been anecdotally linked to the onset of the condition, but no systematic study has proven a link.[citation needed]

Gastroparesis sufferers are disproportionately female. One possible explanation for this finding is that women have an inherently slower stomach emptying time than men.[26] A hormonal link has been suggested, as gastroparesis symptoms tend to worsen the week before menstruation when progesterone levels are highest.[13] Neither theory has been proven definitively.

Mechanism

Gastroparesis can be connected to hypochlorhydria and be caused by chloride, sodium and/or zinc deficiency,[27] as these minerals are needed for the stomach to produce adequate levels of gastric acid (HCl) to properly empty itself of a meal.

On the molecular level, it is thought that gastroparesis can be caused by the loss of neuronal nitric oxide expression since the cells in the GI tract secrete nitric oxide. This important signaling molecule has various responsibilities in the GI tract and in muscles throughout the body. When nitric oxide levels are low, the smooth muscle and other organs may not be able to function properly.[28] Other important components of the stomach are the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) which act as a pacemaker since they transduce signals from motor neurons to produce an electrical rhythm in the smooth muscle cells.[29] Lower nitric oxide levels also correlate with loss of ICC cells, which can ultimately lead to the loss of function in the smooth muscle in the stomach, as well as in other areas of the gastrointestinal tract.[28]

Pathogenesis of symptoms in diabetic gastroparesis include:

- Loss of gastric neurons containing nitric oxide synthase (NOS) is responsible for defective accommodation reflex, which leads to early satiety and postprandial fullness Archived 2020-08-13 at the Wayback Machine.[20]

- Impaired electromechanical activity in the myenteric plexus is responsible for delayed gastric emptying, resulting in nausea and vomiting.[20]

- Sensory neuropathy in the gastric wall may be responsible for epigastric pain.[20]

- Abnormal pacemaker activity (tachybradyarrhythmia) may generate a noxious signal transmitted to the CNS to evoke nausea and vomiting.[20]

Diagnosis

Gastroparesis can be diagnosed with tests such as barium swallow X-rays, manometry, and gastric emptying scans.[30] For the X-ray, the patient drinks a liquid containing barium after fasting which will show up in the X-ray and the physician is able to see if there is still food in the stomach as well. This can be an easy way to identify whether the patient has delayed emptying of the stomach.[31] The clinical definition for gastroparesis is based solely on the emptying time of the stomach (and not on other symptoms), and severity of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with the severity of gastroparesis. Therefore, some patients may have marked gastroparesis with few, if any, serious complications.[citation needed]

In other cases or if the X-ray is inconclusive, the physician may have the patient eat a meal of toast, water, and eggs containing a radioactive isotope so they can watch as it is digested and see how slowly the digestive tract is moving. This can be helpful for diagnosing patients who are able to digest liquids but not solid foods.[31]

-

a-c)Radiologic and endoscopic finding of delayed gastric emptying

-

GI monitoring capsule

Treatment

Treatment includes dietary modifications, medications to stimulate gastric emptying, medications to reduce vomiting, and surgical approaches.[32]

Dietary treatment involves low fiber diets and, in some cases, restrictions on fat and/or solids. Eating smaller meals, spaced two to three hours apart has proved helpful. Avoiding foods like rice or beef that cause the individual problems such as pain in the abdomen or constipation will help avoid symptoms.[33]

Metoclopramide, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, increases contractility and resting tone within the GI tract to improve gastric emptying.[34] In addition, dopamine antagonist action in the central nervous system prevents nausea and vomiting.[35] Similarly, the dopamine receptor antagonist domperidone is used to treat gastroparesis. Erythromycin is known to improve emptying of the stomach but its effects are temporary due to tachyphylaxis and wane after a few weeks of consistent use. Sildenafil citrate, which increases blood flow to the genital area in men, is being used by some practitioners to stimulate the gastrointestinal tract in cases of diabetic gastroparesis.[36] The antidepressant mirtazapine has proven effective in the treatment of gastroparesis unresponsive to conventional treatment.[37] This is due to its antiemetic and appetite stimulant properties. Mirtazapine acts on the same serotonin receptor (5-HT3) as does the popular anti-emetic ondansetron.[38] Camicinal is a motilin agonist for the treatment of gastroparesis.

In specific cases where treatment of chronic nausea and vomiting proves resistant to drugs, implantable gastric stimulation may be utilized. A medical device is implanted that applies neurostimulation to the muscles of the lower stomach to reduce the symptoms. This is only done in refractory cases that have failed all medical management (usually at least two years of treatment).[33] Medically refractory gastroparesis may also be treated with a pyloromyotomy, which widens the gastric outlet by cutting the circular pylorus muscle. This can be done laparoscopically or endoscopically. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy, a procedure in which a part or all of the affected portion of the stomach is removed, has been shown to have some success in the treatment of gastroparesis in obese patients, even curing it in some instances. Further studies have been recommended due to the limited sample size of previous studies.[39][40]

In cases of postinfectious gastroparesis, patients have symptoms and go undiagnosed for an average of 3 weeks to 6 months before their illness is identified correctly and treatment begins.[citation needed]

Prognosis

Post-infectious

Most cases of post-infectious gastroparesis are self‐limiting, with recovery within 12 months of initial symptoms, although some cases last well over 2 years. In children, the duration tends to be shorter and the disease course milder than in adolescent and adults.[32]

Diabetic gastropathy

Diabetic gastropathy is usually slowly progressive, and can become severe and lethal.[citation needed]

Prevalence

Post-infectious gastroparesis, which constitutes the majority of idiopathic gastroparesis cases, affects up to 4% of the American population. Women in their 20s and 30s seem to be susceptible. One study of 146 American gastroparesis patients found the mean age of patients was 34 years with 82% affected being women, while another study found the patients were young or middle aged and up to 90% were women.[32]

There has only been one true epidemiological study of idiopathic gastroparesis which was completed by the Rochester Epidemiology Project. They looked at patients from 1996-2006 who were seeking medical attention instead of a random population sample and found that the prevalence of delayed gastric emptying was four fold higher in women. It is difficult for medical professionals and researchers to collect enough data and provide accurate numbers since studying gastroparesis requires specialized laboratories and equipment.[41]

References

- ↑ Lee, DS; Lee, SJ (2014). "Severe Gastroparesis following Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: Suggestion for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Device for Gastroparesis after RFCA". Case reports in gastrointestinal medicine. 2014: 923637. doi:10.1155/2014/923637. PMID 25614842.

- ↑ "How to pronounce gastroparesis in English". dictionary.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Symptoms & Causes of Gastroparesis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Definition & Facts for Gastroparesis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Camilleri, Michael; Chedid, Victor; Ford, Alexander C.; Haruma, Ken; Horowitz, Michael; Jones, Karen L.; Low, Phillip A.; Park, Seon-Young; Parkman, Henry P.; Stanghellini, Vincenzo (December 2018). "Gastroparesis". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 4 (1): 41. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0038-z. PMID 30385743.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Diagnosis of Gastroparesis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Reddivari, AKR; Mehta, P (January 2021). "Gastroparesis". PMID 31855372.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Treatment for Gastroparesis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Mccallum, Richard; Parkman, Henry; Clarke, John; Kuo, Braden (2020). Gastroparesis: Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis and Treatment. Academic Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-12-818587-2. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ↑ McKenzie, P; Bielefeldt, K (2018). "Glass half empty? Lessons learned about gastroparesis". F1000Research. 7. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14043.1. PMID 29862014.

- ↑ Chandrasekhara, Vinay; Elmunzer, B. Joseph; Khashab, Mouen; Muthusamy, V. Raman (2018). Clinical Gastrointestinal Endoscopy E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-323-54792-5. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ↑ "Gastroparesis: Symptoms". MayoClinic.com. 2012-01-04. Archived from the original on 2012-10-06. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Summary for Oley Foundation by R. W. McCallum, MD". Oley.org. Archived from the original on 2005-12-12. Retrieved 2012-10-09.[unreliable medical source?]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 "Gastroparesis Complications – Mayo Clinic". Archived from the original on 2014-03-31. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ↑ Lisa Sanders MD "Diagnosis" NY Times Magazine 3.4.18 p.16-18.

- ↑ Bharadwaj S, Meka K, Tandon P, Rathur A, Rivas JM, Vallabh H, Jevenn A, Guirguis J, Sunesara I, Nischnick A, Ukleja A (May 2016). "Management of gastroparesis-associated malnutrition". Journal of Digestive Diseases. 17 (5): 285–94. doi:10.1111/1751-2980.12344. PMID 27111029.

- ↑ "10 Ways to Improve Stomach Acid Levels". DrJockers.com. 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ Davis, Mellar P.; Weller, Renee; Regel, Sally (2018), MacLeod, Roderick Duncan; van den Block, Lieve (eds.), "Gastroparesis and Cancer-Related Gastroparesis", Textbook of Palliative Care, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–15, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31738-0_114-1, ISBN 978-3-319-31738-0

- ↑ "Overview". Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Owyang, Chung (2011-10-01). "Phenotypic Switching in Diabetic Gastroparesis: Mechanism Directs Therapy". Gastroenterology. 141 (4): 1134–1137. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.014. ISSN 0016-5085. PMID 21875587. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ "Spotlight on gastroparesis," unauthored article, Balance (magazine of Diabetes UK, no. 246, May–June 2012, p. 43.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Gastroparesis Causes – Mayo Clinic". Archived from the original on 2014-03-31. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ↑ "Gastroparesis". Jackson Siegelbaum Gastroenterology. 2011-11-08. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ↑ "Gastroparesis – Your Guide to Gastroparesis – Causes of Gastroparesis". Heartburn.about.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- ↑ "Gastroparesis: Causes". MayoClinic.com. 2012-01-04. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ↑ "Epocrates article, registration required". Online.epocrates.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ↑ Kohli, Divyanshoo; Majithia, Raj; Shocket, David I; Finelli, Frederick; Koch, Timothy (October 2012). "The Potential Role of Niacin in the Development of Indeterminant Colitis After Bariatric Surgery". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 107: S233. doi:10.14309/00000434-201210001-00561. ISSN 0002-9270.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Oh JH, Pasricha PJ (January 2013). "Recent advances in the pathophysiology and treatment of gastroparesis". Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 19 (1): 18–24. doi:10.5056/jnm.2013.19.1.18. PMC 3548121. PMID 23350043.

- ↑ Al-Shboul OA (2013). "The importance of interstitial cells of cajal in the gastrointestinal tract". Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (1): 3–15. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.105909. PMC 3603487. PMID 23319032.

- ↑ "Gastroparesis Tests and diagnosis – Mayo Clinic". Archived from the original on 2014-03-31. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Gastroparesis". American Diabetes Association. Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Thorn AR (March 2010). "Not just another case of nausea and vomiting: a review of postinfectious gastroparesis". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 22 (3): 125–33. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00485.x. PMID 20236395.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Treatment Options for Gastroparesis". Medtronic.com. Medtronic. 29 September 2014. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ "Metochlopramide Hydrochloride". Monograph. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ Rang, H. P.; Dale, M. M.; Ritter, J. M.; Moore, P. K. (2003). Pharmacology (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-07145-4.[page needed]

- ↑ Gottlieb S (August 2000). "Sildenafil may help diabetic patients". BMJ. 321 (7258): 401A. PMC 1127789. PMID 10938040.

- ↑ Kundu S, Rogal S, Alam A, Levinthal DJ (June 2014). "Rapid improvement in post-infectious gastroparesis symptoms with mirtazapine". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (21): 6671–4. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6671. PMC 4047357. PMID 24914393.

- ↑ Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, Kang HC, Mun JU, Yang SJ, Yoon JS (2006). "Mirtazapine for severe gastroparesis unresponsive to conventional prokinetic treatment". Psychosomatics. 47 (5): 440–2. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.47.5.440. PMID 16959934.

- ↑ Samuel, Bankole; Atiemo, Kofi; Cohen, Phillip; Czerniach, Donald; Kelly, John; Perugini, Richard (2016). "The Effect of Sleeve Gastrectomy on Gastroparesis: A Short Clinical Review". Bariatric Surgical Practice and Patient Care. 11 (2): 84–9. doi:10.1089/bari.2015.0052.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2018-01-26. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)[full citation needed] - ↑ Bharucha, Adil E. (March 2015). "Epidemiology and Natural History of Gastroparesis". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 44 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2014.11.002. ISSN 0889-8553. PMC 4323583. PMID 25667019.

External links

- Overview Archived 2021-03-19 at the Wayback Machine from NIDDK National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases at NIH

- Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L (January 2013). "Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 108 (1): 18–37, quiz 38. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.373. PMC 3722580. PMID 23147521.

- Parkman HP, Fass R, Foxx-Orenstein AE (June 2010). "Treatment of patients with diabetic gastroparesis". Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 6 (6): 1–16. PMC 2920593. PMID 20733935.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from January 2018

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from January 2018

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- All articles with incomplete citations

- Articles with incomplete citations from January 2018

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2020

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- Congenital disorders of digestive system

- Diseases of oesophagus, stomach and duodenum

- Gastrointestinal tract disorders

- Stomach disorders

- RTT