Colonic ulcer

| Colonic ulcer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Colon ucler |

| |

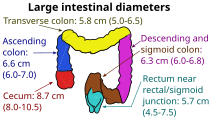

| Diameters of the large intestine | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

Colonic ulcer can occur at any age, in children however they are rare. Most common symptoms are abdominal pain and hematochezia.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Colonic ulcers present differently depending on where and how much of the intestinal wall is affected. Patients may be asymptomatic or exhibit symptoms such as anemia, abdominal pain, hematochezia, chronic gastrointestinal bleeding, and perforation.[2]

Causes

Stercoral ulcers

Stercoral ulceration is a loss of bowel integrity caused by the pressure induced by inspissated feces. The lesion typically manifests as an isolated lesion in the rectosigmoid area in patients who are bedridden and constipated. Perforation and hemorrhage, the main complications, cause a mortality rate higher than 50% due to related diseases in the population at risk. If a patient has a history of constipation and presents with acute abdominal pain and clinical findings consistent with a hollow viscus perforation, the diagnosis of perforated stercoral ulceration should be taken into consideration. The treatment of choice is early celiotomy with aggressive debridement and irrigation of the peritoneal cavity, followed by either resection with proximal colostomy or exteriorization.[3]

Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[4] It is a long-term condition that results in inflammation and ulcers of the colon and rectum.[4][5] The primary symptoms of active disease are abdominal pain and diarrhea mixed with blood (hematochezia). Weight loss, fever, and anemia may also occur. Often, symptoms come on slowly and can range from mild to severe. Symptoms typically occur intermittently with periods of no symptoms between flares. Complications may include abnormal dilation of the colon (megacolon), inflammation of the eye, joints, or liver, and colon cancer.[4][6]

The cause of UC is unknown. Theories involve immune system dysfunction, genetics, changes in the normal gut bacteria, and environmental factors.[4][7] Rates tend to be higher in the developed world with some proposing this to be the result of less exposure to intestinal infections, or to a Western diet and lifestyle.[5][8] Often it begins in people aged 15 to 30 years, or among those over 60.[4] Males and females appear to be affected in equal proportions. It has also become more common since the 1950s.[5] The removal of the appendix at an early age may be protective.[8] Diagnosis is typically by colonoscopy with tissue biopsies.[4]

Dietary changes, such as maintaining a high-calorie diet or lactose-free diet, may improve symptoms. Several medications are used to treat symptoms and bring about and maintain remission, including aminosalicylates such as mesalazine or sulfasalazine, steroids, immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, and biologic therapy. Removal of the colon by surgery may be necessary if the disease is severe, does not respond to treatment, or if complications such as colon cancer develop. Removal of the colon and rectum generally cures the condition.[4][8]

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare benign disease characterized by symptoms, clinical findings, and histological abnormalities.[9] Only 40% of patients have ulcers; 20% of patients have a single ulcer, and the remaining lesions range in size and form from broad-based polypoid to hyperemic mucosa.[10] Clinical signs and symptoms include rectal bleeding, copious mucus discharge, prolonged, severe straining, abdominal and perineal pain, constipation, and, in rare cases, rectal prolapse.[11] Histopathological features of this disease include fibrosis obliterating the lamina propria and smooth muscle fibers extending from a thickened muscularis mucosa to the lumen.[12] SRUS has been treated with a variety of methods, including conservative measures such as diet and bulking agents, medical therapy, biofeedback, and surgery. Treatment is determined by the severity of the symptoms and whether or not there is rectal prolapse.[13]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the world, and their side effects primarily affect the gastrointestinal tract. Although uncommon, colonic involvement is widely known.[2] One study of 425 patients with chronic NSAID use found that 3% of the patients had colonic lesions.[14] Colonic injury is most frequently linked to longer-acting and enteric-coated NSAIDs; the most frequent reports of injury occur after using diclofenac and enteric-coated aspirin.[15] Rectal ulcers and colitis have also been linked to NSAID rectal suppositories. The length of drug use is less significant because patients who have taken the medication for several months to years have been reported to develop colonic ulcers.[2]

Infections

Although many infections involve the colon, only a few of them can cause isolated ulcers.[2]

Tuberculosis

Isolated colonic ulceration is a symptom of intestinal tuberculosis. Ulcers can occur anywhere in the colon, but they are most common on the right side. Usually transverse, the ulcers range in size from 1 to 3 cm. They have a deep base covered in exudate and are frequently accompanied by stricture or a nodule-like appearance around the edge. Biopsy specimens reveal epithelioid granulomas, crypt distortion, and acute and chronic inflammation.[16]

Amebiasis

The colon is the primary site of amebiasis. Sometimes patients present with colon ulceration but no diffuse colitis. In patients who do not have acute diarrhea or colitis, ulcers are usually small, single or multiple, with well-defined margins, more often in the right colon, and surrounded by normal mucosa.[17]

Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is found in the tropics and southeastern United States. The majority of patients have abdominal pain as well as significant peripheral eosinophilia. The small bowel is the most commonly affected. Colonic involvement can cause multiple shallow serpiginous ulcers, erythema, and friability. Inflammation and Strongyloides eggs are discovered during a biopsy. Treatment with ivermectin or thiabendazole has shown efficacy.[18]

Other causes

Up to 25% of Behçet's syndrome patients have gastrointestinal involvement, with ulceration in the ileocolic region being the most common gastrointestinal site. Colonic ulcers are most commonly found in the cecum. Typically, the ulcers are large, round to oval, solitary, relatively deep, and have an undermining edge.[19]

In rare cases, radiotherapy for prostate cancer can result in a non-healing rectal ulcer. A fistula may exacerbate these ulcers, necessitating surgical intervention. Biopsies should be taken to rule out cancer.[20]

Rarely, iron-deficiency anemia can result from ulcers that form at the location of the ileocolonic anastomosis in the absence of inflammatory bowel disease. The cause of the ulceration is unknown, but it is most likely due to local ischemia or NSAID use, which should be avoided. Oral iron replacement therapy can be used to treat the majority of patients.[21]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a patient with isolated large bowel ulceration is based on their presenting symptoms, endoscopic appearance, and the histology of the lesion. Particularly in cases of rectal ulcers, biopsies from the ulcer's margins should be obtained in order to rule out malignancy. Random biopsies of the normal colon mucosa may be taken in patients who have diarrhea or who have a high suspicion of having inflammatory bowel disease.[2]

See also

References

- ^ Kleinman, Ronald E. (1998). Atlas of Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease. PMPH-USA. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-55009-038-3. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Nagar, Anil B. (2007). "Isolated colonic ulcers: Diagnosis and management". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 9 (5). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 422–428. doi:10.1007/s11894-007-0053-9. ISSN 1522-8037. PMID 17991345. S2CID 40823444.

- ^ Maull, K. I.; Kinning, W. K.; Kay, S. (January 1982). "Stercoral ulceration". The American Surgeon. 48 (1): 20–24. ISSN 0003-1348. PMID 7065551.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ulcerative Colitis". NIDDK. September 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Hanauer SB (February 2013). "Ulcerative colitis". BMJ. 346: f432. doi:10.1136/bmj.f432. PMID 23386404. S2CID 14778938.

- ^ Wanderås MH, Moum BA, Høivik ML, Hovde Ø (May 2016). "Predictive factors for a severe clinical course in ulcerative colitis: Results from population-based studies". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 7 (2): 235–241. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i2.235. PMC 4848246. PMID 27158539.

- ^ Akiho H, Yokoyama A, Abe S, Nakazono Y, Murakami M, Otsuka Y, et al. (November 2015). "Promising biological therapies for ulcerative colitis: A review of the literature". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. 6 (4): 219–227. doi:10.4291/wjgp.v6.i4.219. PMC 4644886. PMID 26600980.

- ^ a b c Danese S, Fiocchi C (November 2011). "Ulcerative colitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (18): 1713–1725. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1102942. PMID 22047562.

- ^ Felt-Bersma, Richelle J.F.; Tiersma, E. Stella M.; Cuesta, Miguel A. (2008). "Rectal Prolapse, Rectal Intussusception, Rectocele, Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome, and Enterocele". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 37 (3). Elsevier BV: 645–668. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.001. ISSN 0889-8553. PMID 18794001.

- ^ Tjandra, Joe J.; Fazio, Victor W.; Church, James M.; Lavery, Ian C.; Oakley, John R.; Milsom, Jeffrey W. (1992). "Clinical conundrum of solitary rectal ulcer". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 35 (3). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 227–234. doi:10.1007/bf02051012. ISSN 0012-3706. S2CID 29221249.

- ^ Suresh, N.; Ganesh, R.; Sathiyasekaran, Malathi (March 15, 2010). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: A case series". Indian Pediatrics. 47 (12). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1059–1061. doi:10.1007/s13312-010-0177-0. ISSN 0019-6061. PMID 20453265. S2CID 30325279.

- ^ Tjandra, Joe J.; Fazio, Victor W.; Petras, Robert E.; Lavery, Ian C.; Oakley, John R.; Milsom, Jeffrey W.; Church, James M. (1993). "Clinical and pathologic factors associated with delayed diagnosis in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 36 (2). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 146–153. doi:10.1007/bf02051170. ISSN 0012-3706. S2CID 6671494.

- ^ Zhu, Qing-Chao (2014). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: Clinical features, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment strategies". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (3). Baishideng Publishing Group Inc.: 738–744. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i3.738. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 3921483. PMID 24574747.

- ^ OHKUSA, T.; TERAI, T.; ABE, S.; KOBAYASHI, O.; BEPPU, K.; SAKAMOTO, N.; KUROSAWA, A.; OSADA, T.; HOJO, M.; NAGAHARA, A.; OGIHARA, T.; SATO, N. (2006). "Colonic mucosal lesions associated with long-term administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 24 (s4). Wiley: 88–95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.00030.x. ISSN 0269-2813.

- ^ Püspök, Andreas; Kiener, Hans-Peter; Oberhuber, Georg (2000). "Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 43 (5). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 685–691. doi:10.1007/bf02235589. ISSN 0012-3706. S2CID 25491659.

- ^ Alvares, J. F.; Devarbhavi, H.; Makhija, P.; Rao, S.; Kottoor, R. (2005). "Clinical, Colonoscopic, and Histological Profile of Colonic Tuberculosis in a Tertiary Hospital". Endoscopy (in German). 37 (4). Georg Thieme Verlag KG: 351–356. doi:10.1055/s-2005-861116. ISSN 0013-726X. PMID 15824946. S2CID 260128886.

- ^ Sachdev, Gopal Krishnan; Dhol, Pranita (1997). "Colonic involvement in patients with amebic liver abscess: endoscopic findings". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 46 (1). Elsevier BV: 37–39. doi:10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70207-4. ISSN 0016-5107. PMID 9260703.

- ^ Thompson, Bryan F; Fry, Lucı́a C; Wells, Christopher D; Olmos, Martı́n; Lee, David H; Lazenby, Audrey J; Mönkemüller, Klaus E (2004). "The spectrum of GI strongyloidiasis: an endoscopic-pathologic study". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 59 (7). Elsevier BV: 906–910. doi:10.1016/s0016-5107(04)00337-2. ISSN 0016-5107. PMID 15173813.

- ^ Lee, Chung Ryul; Kim, Won Ho; Cho, Yong Suk; Kim, Myoung Hwan; Kim, Jae Hak; Park, In Suh; Bang, Dongsik (2001). "Colonoscopic Findings in Intestinal Behçet's Disease". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 7 (3). Oxford University Press (OUP): 243–249. doi:10.1097/00054725-200108000-00010. ISSN 1078-0998.

- ^ Shah, Shimul A.; Cima, Robert R.; Benoit, Eric; Breen, Elizabeth L.; Bleday, Ronald (2004). "Rectal Complications After Prostate Brachytherapy". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 47 (9). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1487–1492. doi:10.1007/s10350-004-0603-2. ISSN 0012-3706. S2CID 25922519.

- ^ Chari, Suresh T; Keate, Ray F (2000). "Ileocolonic Anastomotic Ulcers: A Case Series and Review of The Literature". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 95 (5). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1239–1243. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02016.x. ISSN 0002-9270. PMID 10811334. S2CID 1464756.

Further reading

- Maire, F.; Cellier, C.; Cervoni, J. P.; Danel, C.; Barbier, J. P.; Landi, B. (November 1998). "[Dieulafoy colonic ulcer. A rare cause of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage]". Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologique. 22 (11): 958–960. ISSN 0399-8320. PMID 9881274.