Colistin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Xylistin, Coly Mycin M, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antibiotic |

| Main uses | Multidrug-resistant Gram negative infections[1][2] |

| Side effects | Kidney and neurological problems[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Topical, by mouth, intravenous, inhaled |

| Defined daily dose | 9 MU (by mouth) [3] 9 MU (parenteral)[4] 3 MU (inhalation)[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 0% |

| Elimination half-life | 5 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

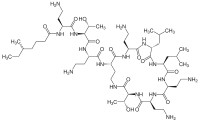

| Formula | C52H98N16O13 |

| Molar mass | 1155.455 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Colistin, also known as polymyxin E, is an antibiotic used as a last-resort for multidrug-resistant Gram negative infections including pneumonia.[1][2] These may involve bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Acinetobacter.[5] It comes in a form which can be injected into a vein or muscle or inhaled, known as colistimethate sodium and one which is applied to the skin or taken by mouth, known as colistin sulfate.[6] Resistance to colistin is beginning to appear as of 2017.[7]

Common side effects of the injectable form include kidney and neurological problems.[2] Other serious side effects may include anaphylaxis, muscle weakness, and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea.[2] The inhaled form may result in constriction of the bronchioles.[2] It is unclear if use during pregnancy is safe for the baby.[8] Colistin is in the polymyxin class of medications.[2] It works by breaking down the cytoplasmic membrane which generally results in bacterial cell death.[2]

Colistin was discovered in 1947 and colistimethate sodium was approved for medical use in the United States in 1970.[5][2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[10] Dosing is complicated and inconsistent.[11] In the United Kingdom it costs the NHS £18 for 10 vials of the injectable form (1 million units in each vial) as of 2021.[10] In the United States the dose is expressed as 'Colistin base' 150mg and costs about US$24 as of 2019.[12] It is derived from bacteria of the Paenibacillus type.[6]

Medical uses

It is in the 'reserve' group of the WHO AWaRe Classification.[13]

Antibacterial spectrum

Colistin has been effective in treating infections caused by Pseudomonas, Escherichia, and Klebsiella species. The following represents MIC susceptibility data for a few medically significant microorganisms:[14][15]

- Escherichia coli: 0.12–128 μg/ml

- Klebsiella pneumoniae: 0.25–128 μg/ml

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa: ≤0.06–16 μg/ml

For example, colistin in combination with other drugs are used to attack P. aeruginosa biofilm infection [16] Biofilms have a low oxygen environment below the surface where bacteria are metabolically inactive and colistin is highly effective in this environment.[17] However, P. aeruginosa reside in the top layers of the biofilm, where they remain metabolically active, this is because surviving tolerant cells migrate to the top of the biofilm via pili motility and form new aggregates via quorum sensing.[18]

Administration and dosage

Forms

Two forms of colistin are available commercially: colistin sulfate and colistimethate sodium .[19] Colistin sulfate is cationic. Colistin sulfate and colistimethate sodium are eliminated from the body by different routes.[20] With respect to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, colistimethate is the inactive prodrug of colistin.[21]

- Colistimethate sodium may be used to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis patients, and it has come into recent use for treating multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection, although resistant forms have been reported.[22][23] Colistimethate sodium has also been given intrathecally and intraventricularly in Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter baumannii [22][24] Some studies have indicated that colistin may be useful for treating infections caused by carbapenem-resistant isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii.[23]

- Colistin sulfate may be used to treat intestinal infections, or to suppress colonic flora.[25] Colistin sulfate is also used as topical creams, powders, and otic solutions.[26]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 9 MU (by mouth)[3] 9 MU (parenteral)[4] and 3 MU (inhalation).[4]

Colistin sulfate and colistimethate sodium may both be given intravenously, but the dosing is complicated and inconsistent.[11] The very different labeling of the parenteral products of colistin methanesulfonate in different parts of the world was first revealed by Li et al.[27] Colistimethate sodium manufactured by Xellia (Colomycin injection) is prescribed in international units[28], but colistimethate sodium manufactured by Parkdale Pharmaceuticals (Coly-Mycin M Parenteral) is prescribed in milligrams[29]:

- Colomycin 1,000,000 units is 80 mg colistimethate;[30]

- Coly-mycin M 150 mg "colistin base" is 360 mg colistimethate or 4,500,000 units.[31]

Colomycin has a recommended intravenous dose of 1 to 3 million units three times daily for individuals weighing 40 kg or more with normal renal function.[32] Coly-Mycin has a recommended dose of 2.5 to 5 mg/kg a day[33] The recommended "maximum" dose for each preparation is different (480 mg for Colomycin and 720 mg for Coly-Mycin), each country has different generic preparations of colistin, and the recommended dose depends on the manufacturer. [34][35]

Colistimethate sodium aerosol (Promixin; Colomycin Injection) is used to treat pulmonary infections, especially in cystic fibrosis. In the UK, the recommended adult dose is 1–2 million units (80–160 mg) nebulised colistimethate twice daily.[36][30] Nebulized colistin has also been used to decrease severe exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[37]

Resistance

The first colistin-resistance gene in a plasmid which can be transferred between bacterial strains was found in 2011 in China and became publicly known in November 2015. [38]The presence of this plasmid-borne mcr-1 gene was confirmed starting December 2015 in South-East Asia, several European countries and the United States[39]

The Société Française de Microbiologie uses a cut-off of 2> mg/l[40], whereas the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (for psuedomas) sets a cutoff of 4 mg/l or less as sensitive, and 4 mg/ml or more as resistant[41]. No standards for measuring colistin sensitivity are given in the US.[42]

The plasmid-borne mcr-1 gene has been found to confer resistance to colistin.[43] The first colistin-resistance gene in a plasmid which can be transferred between bacterial strains was found in 2011 and became publicly known in November 2015.[38][44] This plasmid-borne mcr-1 gene has since been isolated in China,[45] Europe[46] and the United States.[47]

India reported the first detailed colistin-resistance study which mapped 13 colistin-resistant cases recorded over 18 months. It concluded that pan-drug resistant infections, particularly those in the blood stream, have a higher mortality. Multiple other cases were reported from other Indian hospitals.[48][49] Although resistance to polymyxins is generally less than 10% it is more frequent in the Mediterranean and South-East Asia (Korea and Singapore), where colistin resistance rates are continually increasing.[50] Colistin-resistant E. coli was identified in the United States in May 2016.[51]

Use of colistin to treat Acinetobacter baumannii infections has led to the development of resistant bacterial strains. which have also developed resistance to antimicrobial compounds LL-37 and lysozyme, produced by the human immune system.[52]

It's worth noting that not all resistance to colisin and some other antibiotics is due to the presence of resistance genes.[53] Heteroresistance, the phenomenon wherein apparently genetically identical microbes exhibit a range of resistance to an antibiotic,[54] has been observed in some species of Enterobacter since at least 2016[53]

Resistant natural or acquired

Are the following:[55]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Acinetobacter baumannii

- Escherichia coli

- Salmonella spp

- Klebsiella spp.

- Serratia spp.

- Proteus spp.

- Burkholderia spp.

- Enterobacteriaceae

- Proteus spp.

- Serratia marcescens

- Morganella morganii

- Providencia spp.

- Pseudomonas mallei

- Burkholderia cepacia

- Chromobacterium spp.

- Edwardsiella spp.

- Brucella

- Legionella

- Vibrio cholera

Side effects

The main toxicities described with intravenous treatment are nephrotoxicity (damage to the kidneys) and neurotoxicity (damage to the nerves),[56][57]. Neuro- and nephrotoxic effects appear to be transient and subside on discontinuation, in a significant amount of those individuals given therapy or reduction in dose.[56]

At a dose of 160 mg colistimethate IV every eight hours, very little nephrotoxicity is seen.[58][59] Indeed, colistin appears to have less toxicity than the aminoglycosides that subsequently replaced it, and it has been used for extended periods up to six months with no ill effects.[60] The colistin-induced nephrotoxicity is particularly favoured in patients with hypoalbuminemia.[61]

The main toxicity described with aerosolised treatment is bronchospasm,[62] which can be treated or prevented with the use of beta2-agonists such as salbutamol[63]

Mechanism of action

Colistin is a polycationic peptide. These cationic regions interact with the bacterial outer membrane, by displacing magnesium and calcium bacterial counter ions in the lipopolysaccharide. Hydrophobic/hydrophilic regions interact with the cytoplasmic membrane just like a detergent, solubilizing the membrane in an aqueous environment.[50][64]

Pharmacokinetics

No clinically useful absorption of colistin occurs in the gastrointestinal tract. For systemic infection, colistin must, therefore, be given by injection. Colistimethate is eliminated by the kidneys, but colistin is supposed to be eliminated by non-renal mechanism(s) that are as of yet not characterised.[65][66]

History

Colistin was first isolated in Japan in 1947 from a flask of fermenting Bacillus polymyxa var. colistinus by the Japanese scientist Koyama[67] and became available for clinical use in 1959.[11] In the 1980s, polymyxin use was widely discontinued because of nephro- and neurotoxicity. As multi-drug resistant bacteria became more prevalent in the 1990s, colistin started to get a second look as an emergency solution, in spite of toxic effects.[68]

Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of colistin requires the use of three amino acids threonine, leucine, and 2,4-diaminobutryic acid. It is important to synthesis the linear form of colistin before cycliziation. Elongation of non ribosomal peptide biosynthesis begins by a loading module and then the addition of each subsequent amino acid. The subsequent amino acids are added with the help of an adenylation domain (A), a peptidyl carrier protein domain (PCP), an epimerization domain (E), and a condensation domain (C). Cyclization is accomplished by utilizing a thioesterase.[69]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pogue, JM; Ortwine, JK; Kaye, KS (April 2017). "Clinical considerations for optimal use of the polymyxins: A focus on agent selection and dosing". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 23 (4): 229–233. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.023. PMID 28238870.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 "Colistimethate Sodium Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Falagas ME, Grammatikos AP, Michalopoulos A (October 2008). "Potential of old-generation antibiotics to address current need for new antibiotics". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 6 (5): 593–600. doi:10.1586/14787210.6.5.593. PMID 18847400.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kaye, Keith S; Kaye, Donald (2010). "32. Polymyxins (polymyxin B and colistin)". In Bennett., John E.; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin J.; Mandell, Gerald L. (eds.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol. 1 (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone. pp. 469–470. ISBN 9780443068393. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- ↑ Caniaux, I; van Belkum, A; Zambardi, G; Poirel, L; Gros, MF (March 2017). "MCR: modern colistin resistance" (PDF). European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 36 (3): 415–420. doi:10.1007/s10096-016-2846-y. PMID 27873028. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2019-11-23.

- ↑ "Colistimethate (Coly Mycin M) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ↑ Organization, World Health (2019). "World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019". hdl:10665/325771.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 10.0 10.1 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 588-589. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Nation, Roger L; Li, Jian (December 2009). "Colistin in the 21st Century". Current opinion in infectious diseases. 22 (6): 535–543. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328332e672. ISSN 0951-7375. PMID 19797945. Archived from the original on 2018-02-06. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ↑ "Colistimethate Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ↑ Zanichelli, Veronica; Sharland, Michael; Cappello, Bernadette; Moja, Lorenzo; Getahun, Haileyesus; Pessoa-Silva, Carmem; Sati, Hatim; van Weezenbeek, Catharina; Balkhy, Hanan; Simão, Mariângela; Gandra, Sumanth; Huttner, Benedikt (1 April 2023). "The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book and prevention of antimicrobial resistance". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 101 (4): 290–296. doi:10.2471/BLT.22.288614. ISSN 0042-9686. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ↑ "Polymyxin E (Colistin) - The Antimicrobial Index Knowledgebase - TOKU-E". Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ "Colistin sulfate, USP Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ "Colistin". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ Ciofu, Oana; Tolker-Nielsen, Tim (3 May 2019). "Tolerance and Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms to Antimicrobial Agents—How P. aeruginosa Can Escape Antibiotics". Frontiers in Microbiology. 10. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00913. ISSN 1664-302X. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ↑ Chua SL, Yam JK, Sze KS, Yang L (2016). "Selective labelling and eradication of antibiotic-tolerant bacterial populations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms". Nat Commun. 7: 10750. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710750C. doi:10.1038/ncomms10750. PMC 4762895. PMID 26892159.

- ↑ Conly, JM; Johnston, BL (2006). "Colistin: The Phoenix Arises". The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology. 17 (5): 267–269. ISSN 1712-9532. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ Gupta, Sachin; Govil, Deepak; Kakar, Prem N.; Prakash, Om; Arora, Deep; Das, Shibani; Govil, Pradeep; Malhotra, Ashima (2009). "Colistin and polymyxin B: A re-emergence". Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine : Peer-reviewed, Official Publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 13 (2): 49–53. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.56048. ISSN 0972-5229. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ Learning, Jones & Bartlett (2018). 2019 Nurse's drug handbook (Eighteenth ed.). Burlington, MA. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-284-14489-5. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Landman, David; Georgescu, Claudiu; Martin, Don Antonio; Quale, John (2008). "Polymyxins Revisited". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (3): 449–465. doi:10.1128/CMR.00006-08. ISSN 0893-8512. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Towner K J (2008). "Molecular Basis of Antibiotic Resistance in Acinetobacter spp.". Acinetobacter Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-306-43902-5.

{{cite book}}:|archive-url=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (help) - ↑ Karakitsos D, Paramythiotou E, Samonis G, Karabinis A (2006). "Is intraventricular colistin an effective and safe treatment for post-surgical ventriculitis in the intensive care unit?". Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 50 (10): 1309–10. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01126.x. PMID 17067336.

- ↑ Acinetobacter Infections: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional: 2013 Edition: ScholarlyPaper. ScholarlyEditions. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4816-5661-0. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ Das, Parijat; Sengupta, Kasturi; Goel, Gaurav; Bhattacharya, Sanjay (1 July 2017). "Colistin: Pharmacology, drug resistance and clinical applications". Journal of The Academy of Clinical Microbiologists. 19 (2): 77. doi:10.4103/jacm.jacm_31_17. ISSN 0972-1282. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL (2006). "Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections". Lancet Infect Dis. 6 (9): 589–601. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(06)70580-1. PMID 16931410.

- ↑ "Colistimethate sodium dry-filled vials". xellia.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ "Coly-Mycin® M Parenteral" (PDF). FDA.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Colomycin Injection". Summary of Product Characteristics. electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). 18 May 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ↑ "COMMITTEE FOR VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCTS: COLISTIN: SUMMARY REPORT (2)" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. January 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2006. NB. Colistin base has an assigned potency of 30 000 IU/mg

- ↑ "Colomycin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for solution for injection, infusion or inhalation - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ "Coly-Mycin® M Parenteral (Colistimethate for Injection, USP)" (PDF). FDA.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ Young, David C.; Zobell, Jeffery T.; Waters, C. Dustin; Ampofo, Krow; Stockmann, Chris; Sherwin, Catherine M. T.; Spigarelli, Michael G. (2013). "Optimization of anti-pseudomonal antibiotics for cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations: IV. colistimethate sodium". Pediatric Pulmonology. 48 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1002/ppul.22664. ISSN 1099-0496. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ Yahav, D.; Farbman, L.; Leibovici, L.; Paul, M. (January 2012). "Colistin: new lessons on an old antibiotic". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 18 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03734.x. ISSN 1198-743X. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ "Promixin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for Nebuliser Solution". Patient Information Leafle. electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). 12 January 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017.

- ↑ Bruguera-Avila N, Marin A, Garcia-Olive I, Radua J, Prat C, Gil M, Ruiz-Manzano J (2017). "Effectiveness of treatment with nebulized colistin in patients with COPD". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 12: 2909–2915. doi:10.2147/COPD.S138428. PMC 5634377. PMID 29042767.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Liu, Yi-Yun; Wang, Yang; Walsh, Timothy R.; Yi, Ling-Xian; Zhang, Rong; Spencer, James; Doi, Yohei; Tian, Guobao; Dong, Baolei; Huang, Xianhui; Yu, Lin-Feng; Gu, Danxia; Ren, Hongwei; Chen, Xiaojie; Lv, Luchao; He, Dandan; Zhou, Hongwei; Liang, Zisen; Liu, Jian-Hua; Shen, Jianzhong (February 2016). "Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 16 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. ISSN 1474-4457. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- ↑ Forde, Brian M.; Zowawi, Hosam M.; Harris, Patrick N. A.; Roberts, Leah; Ibrahim, Emad; Shaikh, Nissar; Deshmukh, Anand; Ahmed, Mazen A. Sid; Maslamani, Muna Al; Cottrell, Kyra; Trembizki, Ella; Sundac, Lana; Yu, Heidi H.; Li, Jian; Schembri, Mark A.; Whiley, David M.; Paterson, David L.; Beatson, Scott A. (31 October 2018). "Discovery of mcr-1-Mediated Colistin Resistance in a Highly Virulent Escherichia coli Lineage". mSphere. 3 (5). doi:10.1128/mSphere.00486-18. ISSN 2379-5042. Archived from the original on 25 August 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ Fosse, T.; Giraud-Morin, C.; Madinier, I. (January 2003). "Induced colistin resistance as an identifying marker for Aeromonas phenospecies groups". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 36 (1): 25–29. doi:10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01257.x. ISSN 1472-765X. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "BSAC to actively support the EUCAST Disc Diffusion Method for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing in preference to the current BSAC Disc Diffusion Method" (PDF). British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ↑ Ezadi, Fereshteh; Ardebili, Abdollah; Mirnejad, Reza (28 March 2019). "Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for Polymyxins: Challenges, Issues, and Recommendations". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 57 (4). doi:10.1128/JCM.01390-18. ISSN 0095-1137. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ↑ Gharaibeh, Mohammad H.; Shatnawi, Shoroq Q. (November 2019). "An overview of colistin resistance, mobilized colistin resistance genes dissemination, global responses, and the alternatives to colistin: A review". Veterinary World. 12 (11): 1735–1746. doi:10.14202/vetworld.2019.1735-1746. ISSN 0972-8988. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ Zhang, Sarah. "Resistance to the Antibiotic of Last Resort Is Silently Spreading". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

- ↑ Fong, I. W.; Shlaes, David; Drlica, Karl (2018). Antimicrobial Resistance in the 21st Century. Springer. p. 128. ISBN 978-3-319-78538-7. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ Maryn McKenna (2015-12-03). "Apocalypse Pig Redux: Last-Resort Resistance in Europe". Phenomena. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ "First discovery in United States of colistin resistance in a human E. coli infection". www.sciencedaily.com. Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ↑ "Emergence of Pan drug resistance amongst gram negative bacteria! The First case series from India". December 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-12-31. Retrieved 2014-12-31.

- ↑ "New worry: Resistance to 'last antibiotic' surfaces in India". 28 December 2014. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Bialvaei AZ, Samadi Kafil H (19 March 2015). "Colistin, mechanisms and prevalence of resistance". Curr Med Res Opin. 31 (4): 707–21. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1018989. PMID 25697677.

- ↑ "Discovery of first mcr-1 gene in E. coli bacteria found in a human in United States". cdc.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 31 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-07-11. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Napier BA, Burd EM, Satola SW, Cagle SM, Ray SM, McGann P, Pohl J, Lesho EP, Weiss DS (21 May 2013). "Clinical Use of Colistin Induces Cross-Resistance to Host Antimicrobials in Acinetobacter baumannii". mBio. 4 (3): e00021–13–e00021–13. doi:10.1128/mBio.00021-13. PMC 3663567. PMID 23695834.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Common 'Superbug' Found to Disguise Resistance to Potent Antibiotic". wsj.com. Wall Street Journal. 6 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-04-03. Retrieved 1 Nov 2018.

- ↑ El-Halfawy OM, Valvano MA (2015). "Antimicrobial Heteroresistance: an Emerging Field in Need of Clarity". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 28 (1): 191–207. doi:10.1128/CMR.00058-14. PMC 4284305. PMID 25567227.

- ↑ Aghapour, Zahra; Gholizadeh, Pourya; Ganbarov, Khudaverdi; Bialvaei, Abed Zahedi; Mahmood, Suhad Saad; Tanomand, Asghar; Yousefi, Mehdi; Asgharzadeh, Mohammad; Yousefi, Bahman; Kafil, Hossein Samadi (24 April 2019). "Molecular mechanisms related to colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae". Infection and Drug Resistance. 12: 965–975. doi:10.2147/IDR.S199844. ISSN 1178-6973. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Spapen, Herbert; Jacobs, Rita; Van Gorp, Viola; Troubleyn, Joris; Honoré, Patrick M (25 May 2011). "Renal and neurological side effects of colistin in critically ill patients". Annals of Intensive Care. 1: 14. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-1-14. ISSN 2110-5820. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Li J, Nation RL, Milne RW, Turnidge JD, Coulthard K (2005). "Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 25 (1): 11–25. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.10.001. PMID 15620821.

- ↑ Lim, Lauren M.; Ly, Neang; Anderson, Dana; Yang, Jenny C.; Macander, Laurie; Jarkowski, Anthony; Forrest, Alan; Bulitta, Jurgen B.; Tsuji, Brian T. (December 2010). "Resurgence of Colistin: A Review of Resistance, Toxicity, Pharmacodynamics, and Dosing". Pharmacotherapy. 30 (12): 1279–1291. doi:10.1592/phco.30.12.1279. ISSN 0277-0008. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ↑ Littlewood JM, Koch C, Lambert PA, Høiby N, Elborn JS, Conway SP, Dinwiddie R, Duncan-Skingle F (2000). "A ten year review of Colomycin". Respir. Med. 94 (7): 632–40. doi:10.1053/rmed.2000.0834. PMID 10926333.

- ↑ Stein A, Raoult D (2002). "Colistin: an antimicrobial for the 21st century?". Clin Infect Dis. 35 (7): 901–2. doi:10.1086/342570. PMID 12228836.

- ↑ Giacobbe, Daniele Roberto; di Masi, Alessandra; Leboffe, Loris; Del Bono, Valerio; Rossi, Marianna; Cappiello, Dario; Coppo, Erika; Marchese, Anna; Casulli, Annarita; Signori, Alessio; Novelli, Andrea (December 2018). "Hypoalbuminemia as a predictor of acute kidney injury during colistin treatment". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 11968. Bibcode:2018NatSR...811968G. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30361-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6086859. PMID 30097635.

- ↑ Maddison J, Dodd M, Webb AK (1994). "Nebulized colistin causes chest tightness in adults with cystic fibrosis". Respir. Med. 88 (2): 145–7. doi:10.1016/0954-6111(94)90028-0. PMID 8146414.

- ↑ Kamin W, Schwabe A, Krämer I (2006). "Inhalation solutions: which one are allowed to be mixed? Physico-chemical compatibility of drug solutions in nebulizers". J. Cyst. Fibros. 5 (4): 205–213. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2006.03.007. PMID 16678502.

- ↑ "Colistin: An Update on the Antibiotic of the 21st Century". Medscape. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ↑ Grégoire, Nicolas; Aranzana-Climent, Vincent; Magréault, Sophie; Marchand, Sandrine; Couet, William. "Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Colistin". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 56 (12): 1441–1460. doi:10.1007/s40262-017-0561-1. ISSN 1179-1926. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Couet, W.; Grégoire, N.; Marchand, S.; Mimoz, O. (January 2012). "Colistin pharmacokinetics: the fog is lifting". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 18 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03667.x. ISSN 1198-743X. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ↑ Ahmed, Mohamed Abd El-Gawad El-Sayed; Zhong, Lan-Lan; Shen, Cong; Yang, Yongqiang; Doi, Yohei; Tian, Guo-Bao (1 January 2020). "Colistin and its role in the Era of antibiotic resistance: an extended review (2000–2019)". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 9 (1): 868–885. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1754133. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ Falagas M, Kasiakou S (2005). "Colistin: The Revival of Polymyxins for the Management of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections". Rev Anti Infect Agen. 40 (9): 1333–41. doi:10.1086/429323. PMID 15825037.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Dewick, Paul M. (2009). "Peptides, Proteins, and Other Amino Acid Derivatives". Medicinal natural products : a biosynthetic approach (3rd ed.). Chichester, U.K.: Wiley. pp. 421–484. ISBN 978-0-470-74276-1. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Drug information from the NIH about colistimethate sodium Archived 2019-11-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Drug information from the NIH about colistin sulfate Archived 2019-11-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Colistin topics page (bibliography)". Science.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-11-04. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- "Protocol for PCR detection of the gene mcr-1 gene" (PDF). National Food Institute. Technical University of Denmark. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-15. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- Reardon, Sara (21 December 2015). "Spread of antibiotic-resistance gene does not spell bacterial apocalypse — yet". Trend Watch. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.19037. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1 maint: date format

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- CS1 maint: url-status

- CS1 maint: uses authors parameter

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Articles with changed CASNo identifier

- Articles with changed EBI identifier

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Polymyxin antibiotics

- Cyclic peptides

- RTT

- World Health Organization essential medicines